- Sculptor: Augustus Saint Gaudens

- Pedestal: Original bluestone pedestal by Saint Gaudens and Stanford White; granite copy by Works Progress Administration artists, 1935

- Dedicated: 1880

- Medium and size: Bronze (7.5 feet), granite pedestal (8.75 feet)

- Location: North end of Madison Square (near Fifth Avenue and 26th Street)

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880; pedestal by Stanford White. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

This essay is from Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide (“OMOM” below).

About the sculpture

Few works have altered the course of American sculpture. This is one of them.

For most of the nineteenth century the neoclassical style dominated American sculpture. Ward’s Washington, Brown’s Lincoln (OMOM #6, 15), and Pickett’s Samuel F.B. Morse (Central Park) have capes that might almost be togas. The Statue of Liberty is dressed like a Greek. Symbols of the Roman Republic, such as the fasces, appear frequently (Washington, Washington Arch; OMOM #6, 12). In an extreme instance that startled even his contemporaries, Horatio Greenough portrayed Washington in 1841 as Olympian Zeus, bare to the waist and seated on a throne.

Farragut, by contrast, wears the uniform of a Civil-War naval officer, accurately depicted right down to the eagles on the buttons. He carries binoculars in one hand and lifts his head to scan the distance, bracing his feet as if on a heaving deck. The front of his knee-length coat blows open with the wind of his ship’s motion.

These details add up to a major difference from earlier portraits. Farragut looks as if he were doing his job – commanding a fleet – rather than posing for a portrait. “He is so quiet,” commented Lorado Taft, “that he seems to move.” It was an extraordinary innovation, but not the only one Saint Gaudens incorporated into this memorial.

Pedestals of portrait statues were typically simple and rectangular with a few inscribed lines, intended only to raise the figure above the passing throng. Typical are the Lafayette and Washington at Union Square (OMOM #14, 13)—both familiar to Saint Gaudens.

Departing from this norm, Saint Gaudens requested the assistance of his friend architect Stanford White to create a pedestal that adds to the viewer’s knowledge of Farragut’s character and actions.

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880; pedestal by Stanford White. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

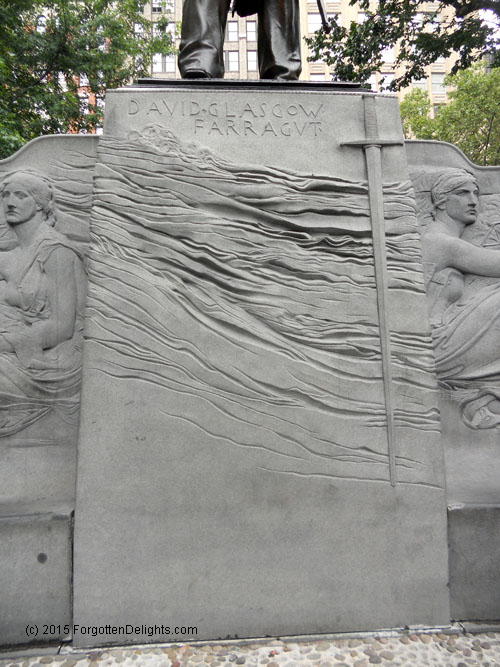

For the broad stone base, Saint Gaudens designed figures in relief of Loyalty (on the left) and Courage (on the right, wearing a breastplate). A lengthy inscription in elegant lettering describes Farragut’s achievements.

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880; pedestal by Stanford White. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880; pedestal by Stanford White. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Augustus Saint Gaudens, General David Glasgow Farragut, 1880; pedestal by Stanford White. Madison Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

The background is an irregular series of waves, the terminals leaping fish. Since the original stone had a bluish tint, the whole pedestal recalled the sea.

Although the pedestal is considerably larger than Farragut, it’s calculated to draw attention to him. The upper edge slants gently up toward the center, where two vertical lines draw our gaze up to the figure. The upward movement is continued by the vertical lines of Farragut’s legs and sword and the double line of buttons. Without conscious effort, our eyes finish on Farragut’s face – a relatively small part of the composition.

The pedestal is also designed to draw us near. Its ends curve forward, so we can’t read the complete inscription unless we mount the steps. Doing so, we find a charming detail: a bronze crab bearing the names of Saint Gaudens and Stanford White set into the pebble-strewn concrete.

The Farragut Monument was a turning point for American sculpture because it not only conveyed the subject’s physical appearance but revealed that he was a far-sighted, courageous naval leader, all the while encouraging us to linger, look at the details and think about the importance of Farragut the man. Even today, it remains a remarkable achievement.

About the subject

Ironclads are “cowardly things,” said David Glasgow Farragut (7/5/1801-8/14/1870), the first officer in the United States Navy to be promoted to the rank of admiral. Ericsson’s Monitor (see OMOM #2) had beaten the Confederate ironclad Merrimac at Hampton Roads in 1862, and dozens of monitor-style ships were being built. But Farragut didn’t consider them a magic bullet, favoring “iron hearts and wooden ships.”

Having served in the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War (1846-48), Farragut was one of the most experienced Civil-War naval commanders. He led the forces that captured New Orleans in 1862, putting nearly all the Mississippi River into Union hands and splitting the South in half. In 1864 he was ordered to capture Mobile Bay, the South’s best remaining port on the Gulf of Mexico and a haven for ships running the Union blockade.

Mobile Bay’s first line of defense was a string of “torpedoes,” floating barrels filled with gunpowder and rigged to explode if a passing ship touched a fuse. A narrow channel east of the torpedoes was guarded by the guns of Fort Morgan. Beyond, the Bay was defended by the South’s most formidable ironclad, the Tennessee.

On August 5, 1864, Farragut arrayed his eighteen ships for battle. Four ironclads at the head of the line were to bear the brunt of Fort Morgan’s attack, and chase the Tennessee if she retreated into shallow water. Wooden screw-propelled vessels followed, lashed to small side-wheel steamers.

As the ships entered the Bay, the over-eager captain of the leading ironclad turned too quickly. His ship’s unarmored belly was ripped open by a mine. In minutes she went down, with over a hundred hands.

The remaining ships milled about under the murderous guns of Fort Morgan. Informed of the crisis, Farragut, who had clambered up the shrouds of his flagship in order to see above the guns’ smoke, shouted “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” Moving his flagship to the head of the line, he led the fleet into the Bay. Although the breathless crews heard mines rubbing against their boats’ hulls, no others detonated. Within three hours the Tennessee surrendered and the last major port on the Gulf coast fell into Union hands.

Farragut in the Shrouds

At the Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5, 1864), Farragut clung precariously to the mainmast. His officers finally persuaded him to run a line to his waist in case he should be wounded and fall. Periodicals in New York elaborated this into the image of the admiral lashed to the mast, like Odysseus facing the Sirens. In World War I, the image was fashioned into a Navy recruitment poster.

Augustus Saint Gaudens and the Commission for the Farragut Statue

John Quincy Adams Ward, at the time America’s most prominent sculptor, was offered the Farragut commission. Ward turned the commission down, but strongly recommended a young sculptor who had just returned from six years’ study in Europe. Farragut was Augustus Saint Gaudens’s big break.

Saint Gaudens (1848-1907) is arguably the greatest sculptor America has produced. Born in Dublin, he was brought to New York City as an infant. He worked as a cameo-cutter while studying art at Cooper Union, then studied for several years in Paris. Farragut, 1881, was his first major commission. Other significant works include the Puritan, 1886 (Springfield, Mass.); the Standing Lincoln, 1887 (Chicago); the Adams Memorial, 1891 (Washington), and the Shaw Memorial, 1897 (Boston).

Aside from Farragut, Manhattan has Cooper and Sherman, 1903. The Metropolitan Museum’s American Wing has several of his works, including Diana, 1894 (a copy of the weathervane from Madison Square Tower). Staten Island has Robert Richard Randall, 1884, at Snug Harbor, and Brooklyn has the David Stewart Memorial, 1883, in the Green-Wood Cemetery. At Theodore Roosevelt’sinvitation, Saint Gaudens designed the famous “Walking Liberty” ten-dollar gold piece in 1906.

For more on Saint Gaudens, see “Artist-Entrepreneurs: Saint Gaudens, MacMonnies, and Parrish,” soon (mid-2019) to be available on Amazon.

An Artist’s First Glimpse of Farragut

Maitland Armstrong, a painter of some renown in his time, wrote to his friend Saint Gaudens:

When I went over to see your statue this morning, and saw the whole thing there before me, it fairly took my breath away, and brought my heart into my mouth. It is perfectly magnificent. I haven’t felt so about anything for years. The sight of such a thing renews one’s youth, and makes one think that life is worth living after all. I felt as I have only done about a few things in my life … I was surprised to see how the rabble about the statue spoke of it, and how they seemed to be touched by it. It is a revelation to them, and what is more, I feel that they are ready and longing for better art. It cheers one to think it. — Maitland Armstrong to Saint Gaudens, 1880; from Saint Gaudens’ Reminiscences, 1913

Farragut’s Fate

Fifty-five years after Farragut was dedicated, it had fallen into a sorry state, as reported in the New York Times in 1935:

And Admiral Farragut – but Admiral Farragut, standing on top of what looks distressingly like the pilot house of an abandoned barge, is another story and a sadder one. … It is the fury of the weather gods that has brought the Farragut statue in Madison Square to its present pitiful pass. The figure of the admiral is in bronze and needs only a loving touch or two, but the state of his beautiful base is truly lamentable. It was cut from bluestone, a material used perhaps for its soft surface and its marine color, or perhaps, as Saint-Gaudens’s biography is said to suggest, for reasons of economy. The bench and the back with its waves and its figures in low relief has given rest and pleasure to generations of New Yorkers. … If man has had half a century of pleasure in it, the elements have had that much time to work with it. The foundation has given way, every joint has opened up, the carving is so loose that tapping would almost shake it off. It is the measured opinion of Park Department experts that while foundations and joints could be fixed the condition of the surface is such that repair is no longer possible. They talk wistfully of wanting to preserve so great a work of art by reproducing it (by a simple process which all sculptors know and make use of) in granite. But the cost for materials is more than they can pay with present funds, and so as a measure of safety, and until some wise donor comes forward to save for the city one of its chief treasures, they have covered it against the elements.

The current feeling is that when a piece of sculpture is done it is done, and no one has to bother about it any longer. Look at the work of Phidias, Americans say, and all those old Roman statues that stand around museums. Nobody did anything about them, and they have endured all these years. … Fortunately, the depression has ended that situation. The present Park Department has Federal funds with which to pay labor and the disposition to employ it on proper care of the statuary population. — Mildred Adams, “Our Statues Regain Places in the Sun,” New York Times 7/21/1935

Copying the base was undertaken later in 1935, as a Works Progress Administration project with federal funding. The original bluestone base is preserved at Saint Gaudens’ summer home in Cornish, NH.

More

- Stanford White, who designed the base and whose name appears with Saint Gaudens’s on the pebbled “beach” at the foot of the pedestal, was James Gordon Bennett, Jr.’s favorite architect. For more of his projects, see the Bennett Memorial.

- On the first ironclad, the Monitor, see Ericsson.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.