One of my major projects in the past few years was writing more than 60 episodes (4-5 mins. each) for a videoguide app on Central Park from Guides Who Know. For the app, I collected hundreds of images of Central Park during the 19th century. I find this year-by-year archival view fascinating, so I’m sharing it by uploading a half dozen or so images per week. See this page for links to all the pages of images.

For blog posts on specific aspects of Central Park, click on Central Park in the Obsessions cloud at lower right. For an overview of the early years of the Park, see Central Park: The Early Years, which includes some of the images on these pages.

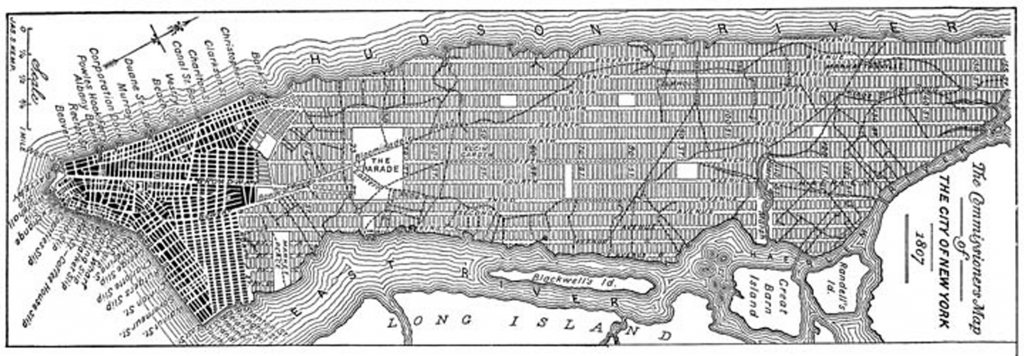

New York, 1811 and onward: the Commissioners’ Plan

North is to the right. The area in black is already built up. The areas in white were slated to be parks. The largest of those, labeled “The Parade,” is approximately where Washington Square Park is.

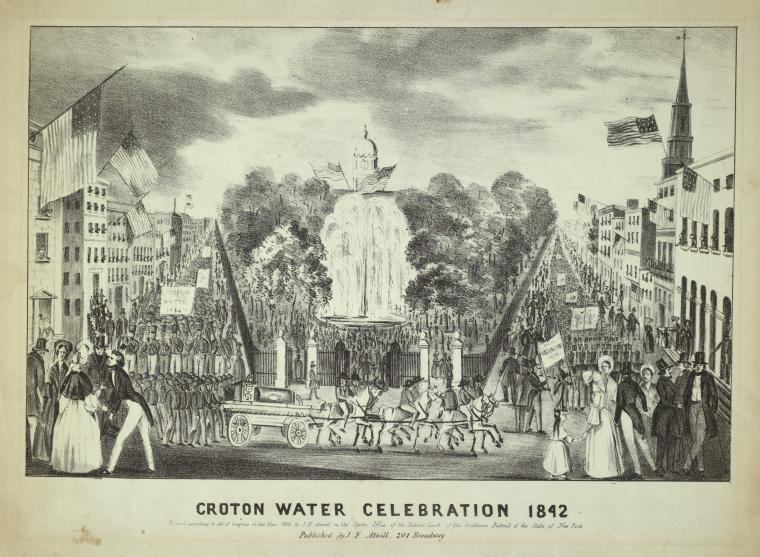

Croton Reservoir, 1842

Celebration at City Hall Park of the opening of the Croton Aqueduct.

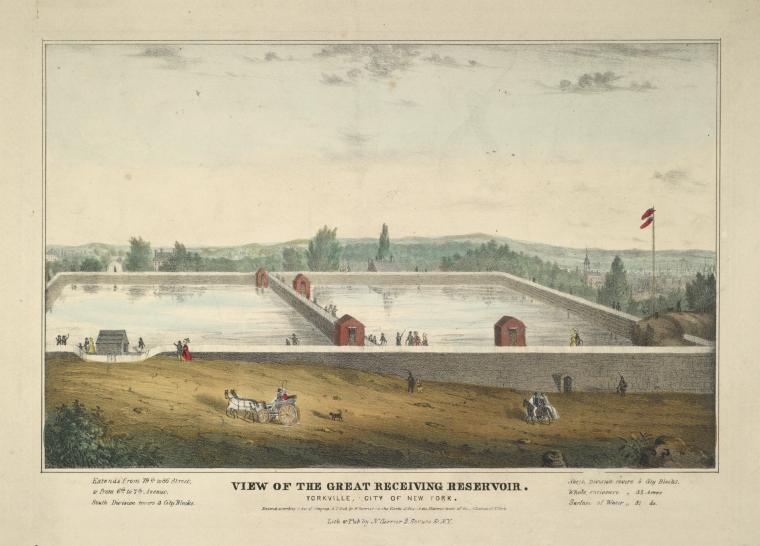

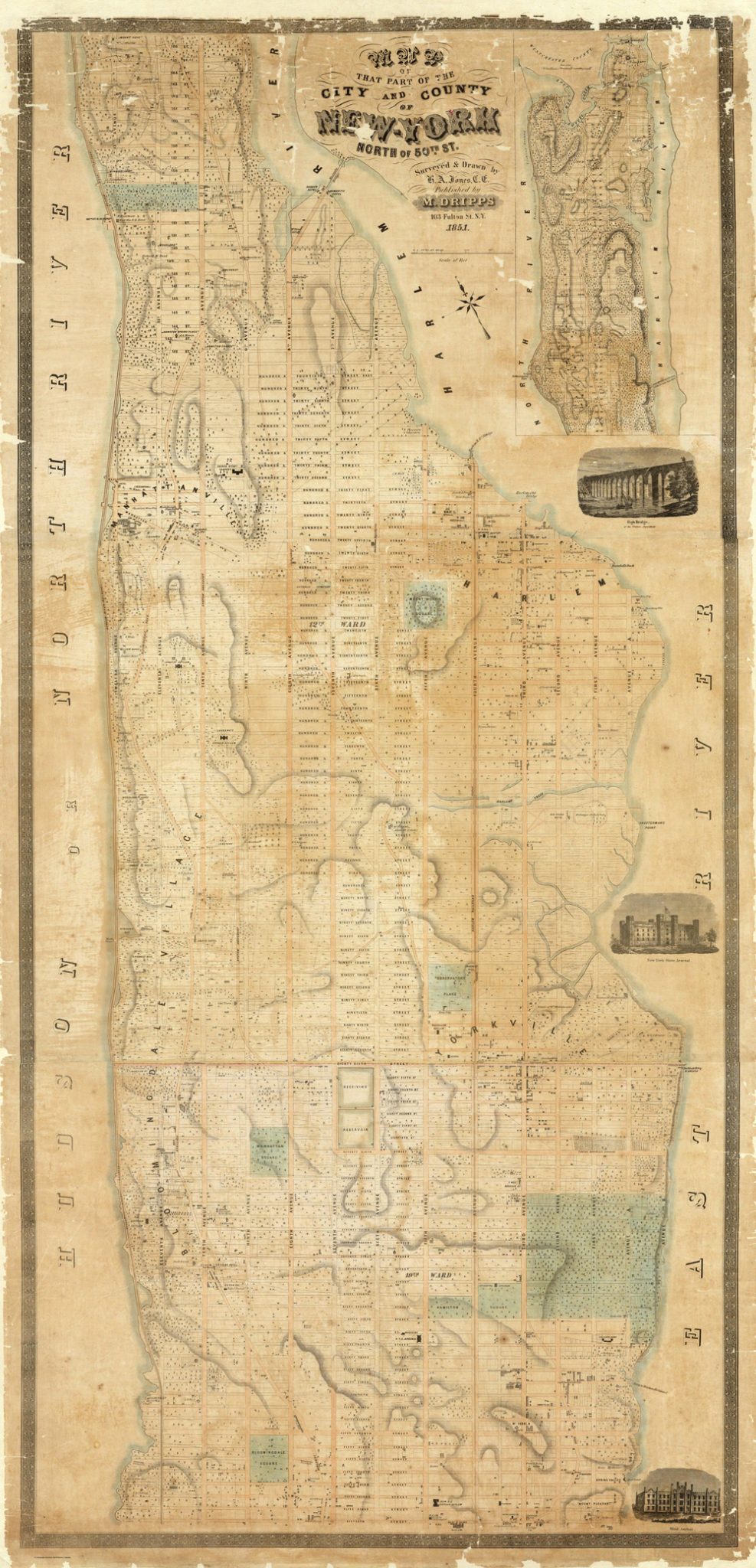

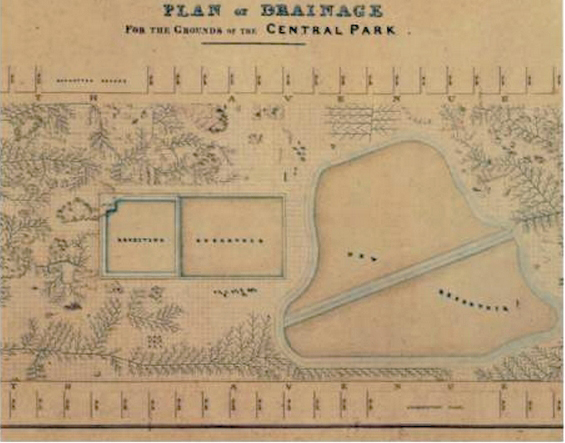

Central Park was originally laid out symmetrically around the original Croton Reservoir.

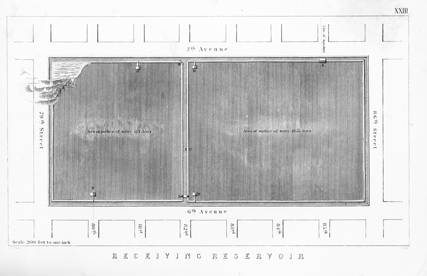

In this map of the Reservoir in the Manhattan street grid, north is to the right: the reservoir ended at 86th Street, where a few pieces of its wall are still visible behind the NYPD precinct. The rock at the left (southwest) is where the Belvedere now stands.

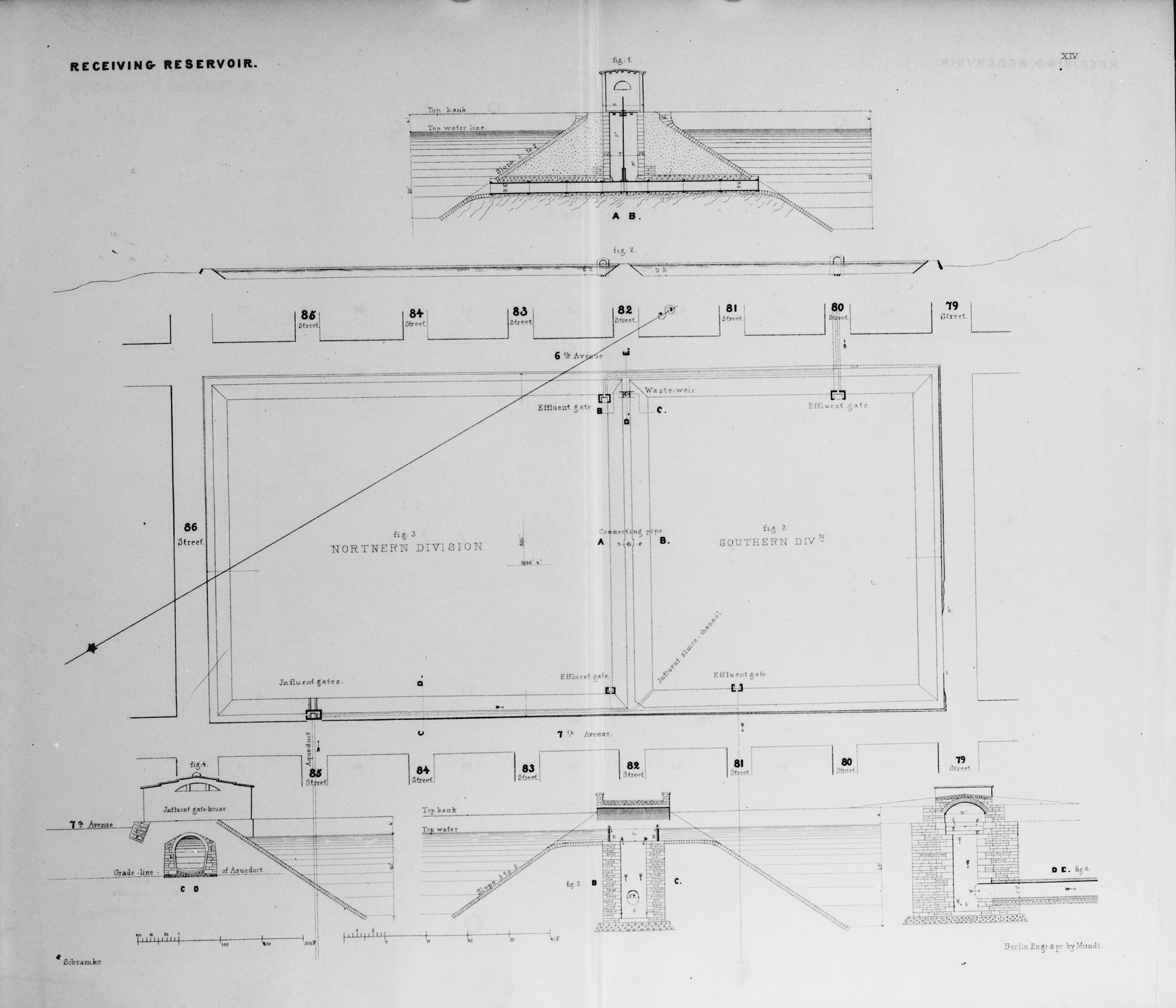

Plan of the receiving reservoir, dated 1843.

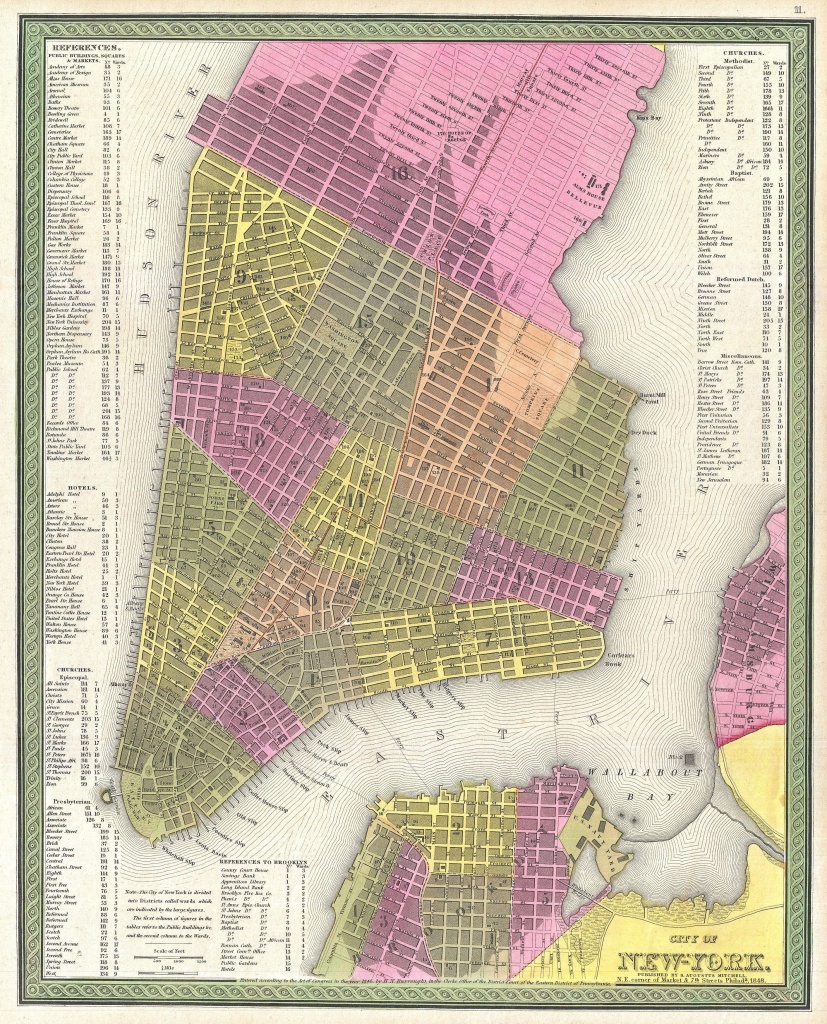

1848: New York

Choosing a site and a plan for the Park

Seneca Village in the 1850s. It was on the west side of what is now Central Park, in the 80s.

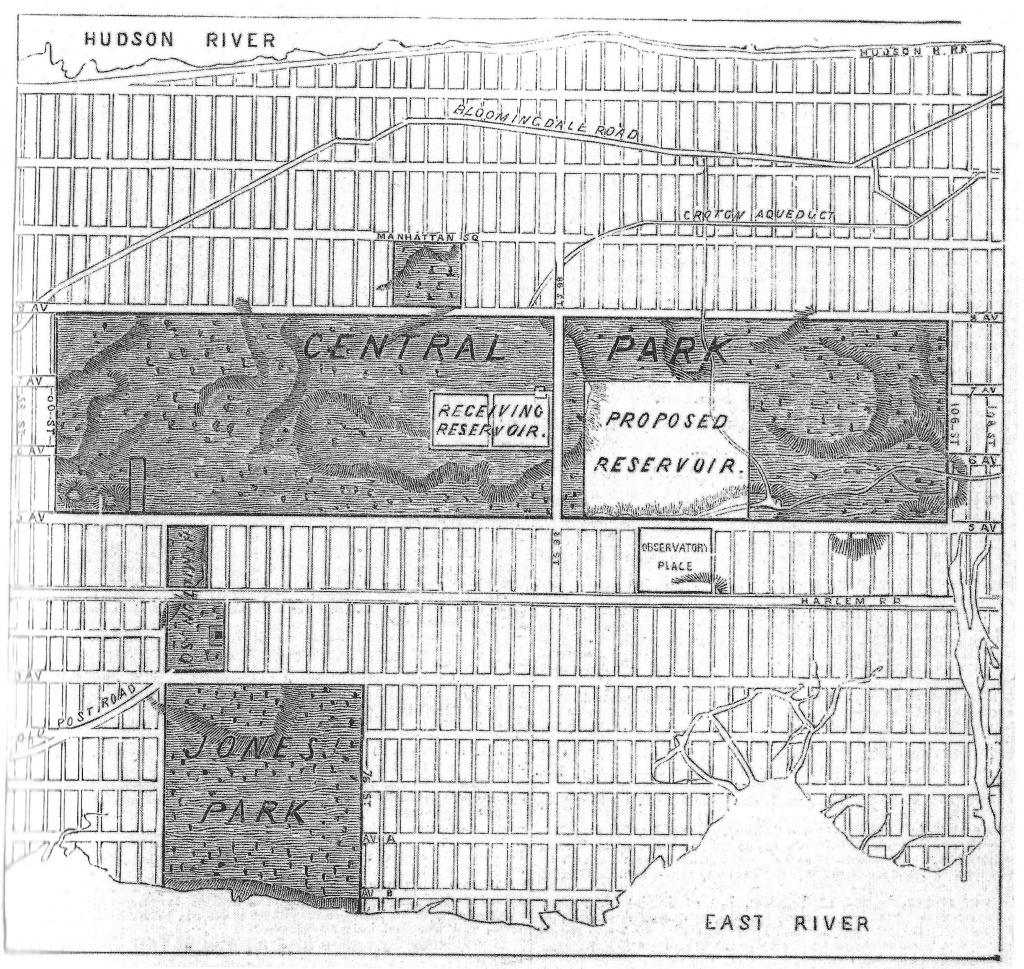

1853: Possible sites for the park

1856

1857

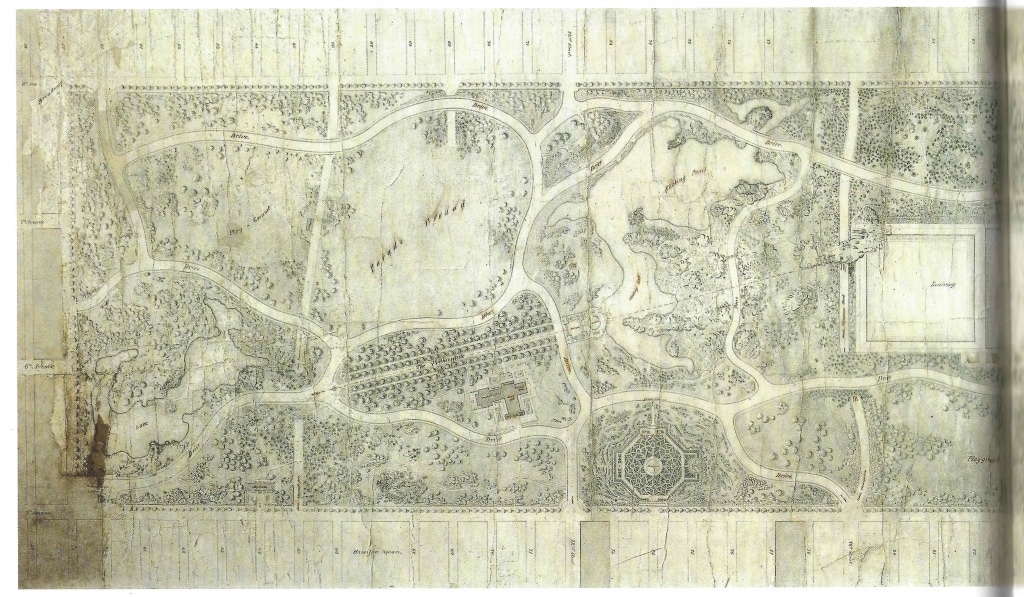

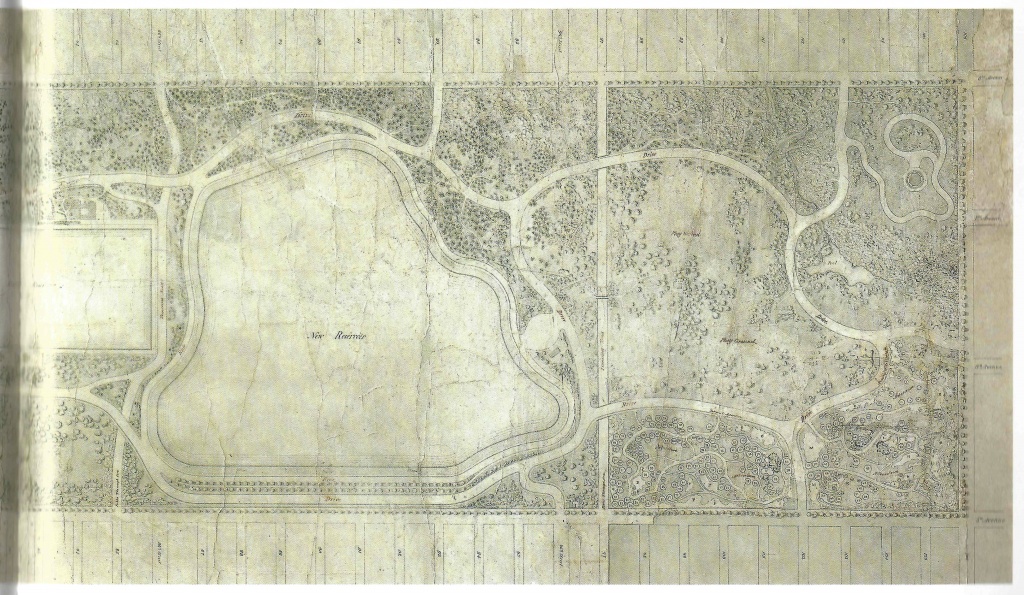

Egbert Ludovicus Viele’s topographical sketch of Central Park, published in the report of the Board of Commissioners for 1857. The Board’s first annual report is here on Google, here on the New York City Parks Department’s site, but neither one includes a scan of this and the following map.

More on Viele in this post.

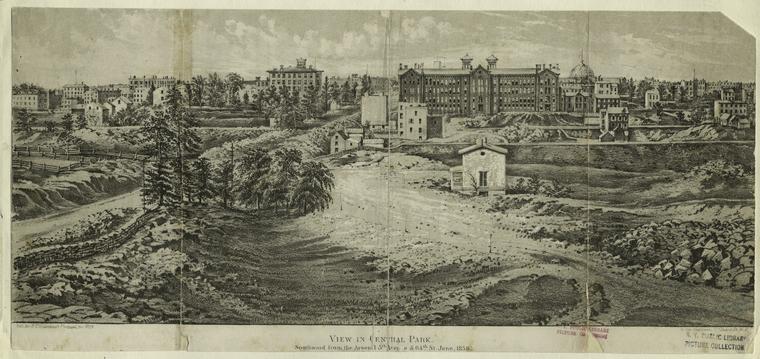

Viele’s report to the Board of Commissioners, published in their Annual Report for 1857, included three sweeping views. This one shows the view west from Summit Rock, where the Belvedere now stands (79th Street). The original reservoir is to our right (north).

This is the view from Bellevue Rock looking north. That’s Mount St. Vincent in the center (around 106th St.). I haven’t pinned down the location of Bellevue Rock. Viele’s report says only:

All through the upper portions of the park, superb views may be obtained from prominent points: Vista rock, Summit rock, Mount Prospect, Bellevue rock, and Mount St. Vincent, embrace views of the Hudson and East rivers, the entire city, Long Island, and Long Island Sound … a complete panorama of New York city and its suburbs. Three of these views accompany this report.” (Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners, 1857, p. 42)

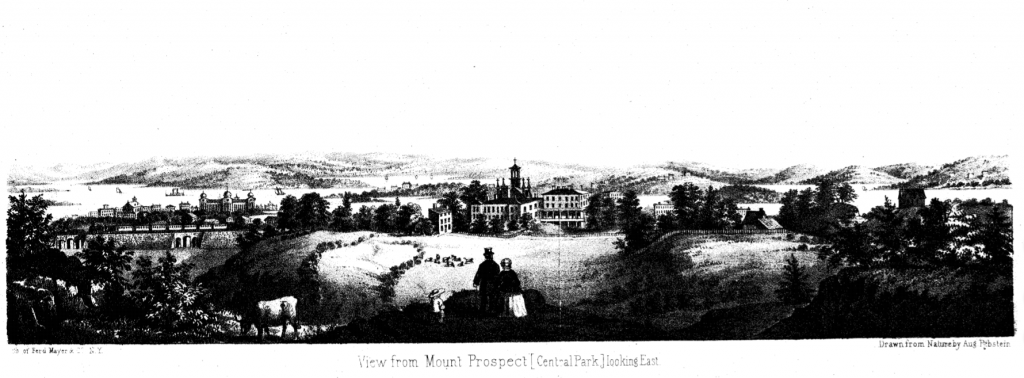

The third view in the 1857 Annual Report is from Mt. Prospect. That’s Mt. St. Vincent in the center again, so perhaps Mt. Prospect is the site now called the Great Hill, on the west side of the Park at about 106th Street.

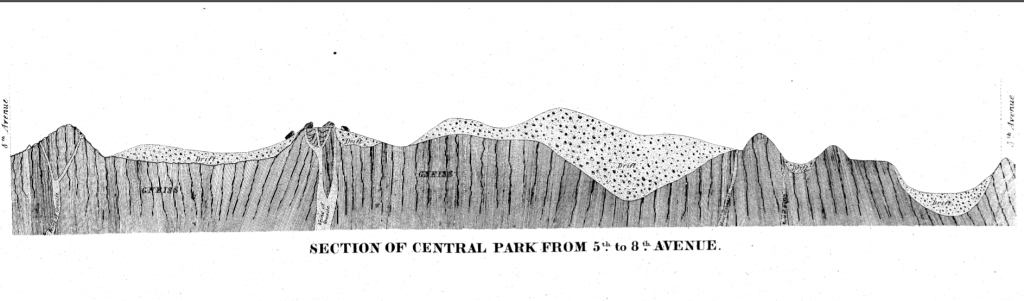

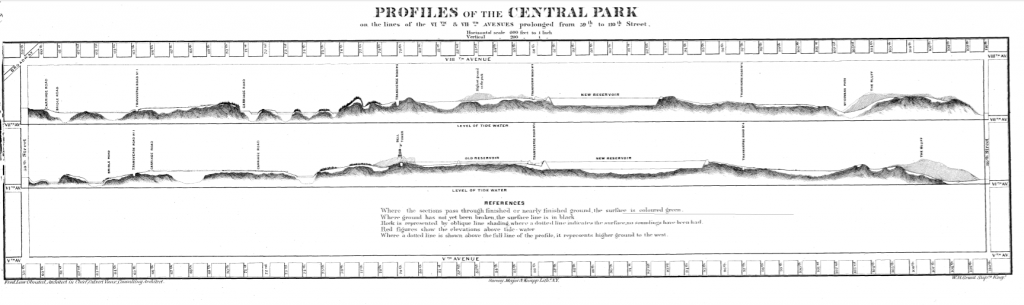

Viele also included a cross-section of the Park from Eighth to Fifth Avenues, which serves as a reminder of how difficult the terrain was.

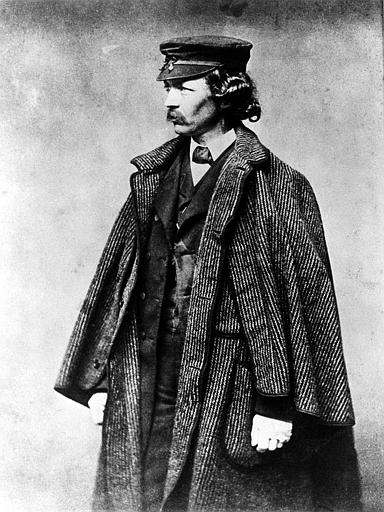

Frederick Law Olmsted in his position as Park superindentent, 1857. I’ve seen this one so often that I have no idea who to credit for the image.

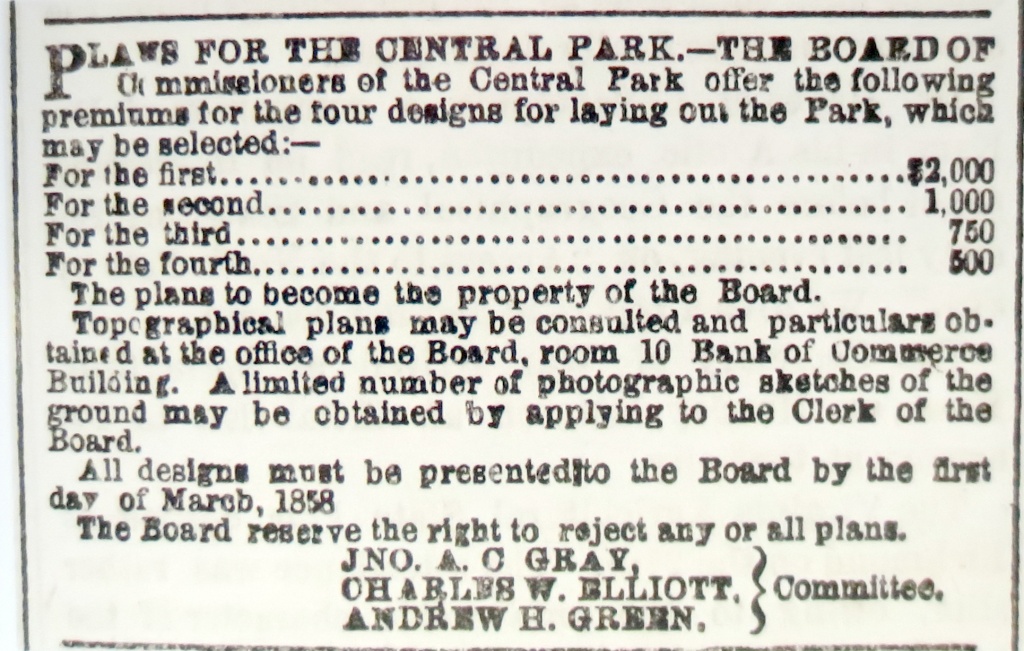

1857-1858: Competition for a plan for the Park

In 1857, the Board of Commissioners ran this ad seeking plans for Central Park.

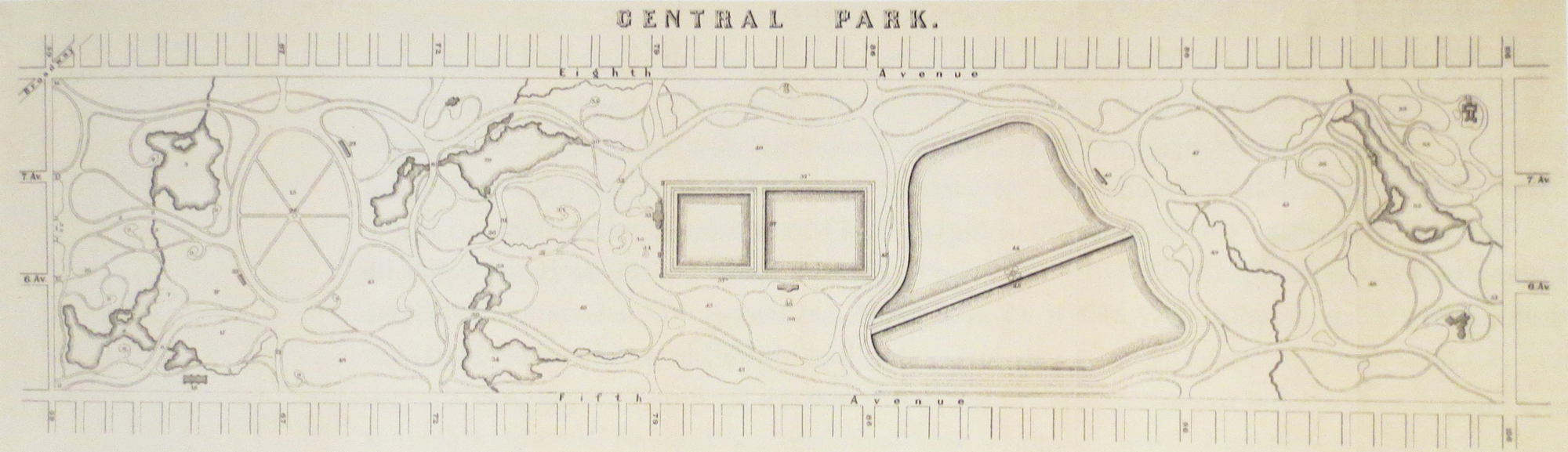

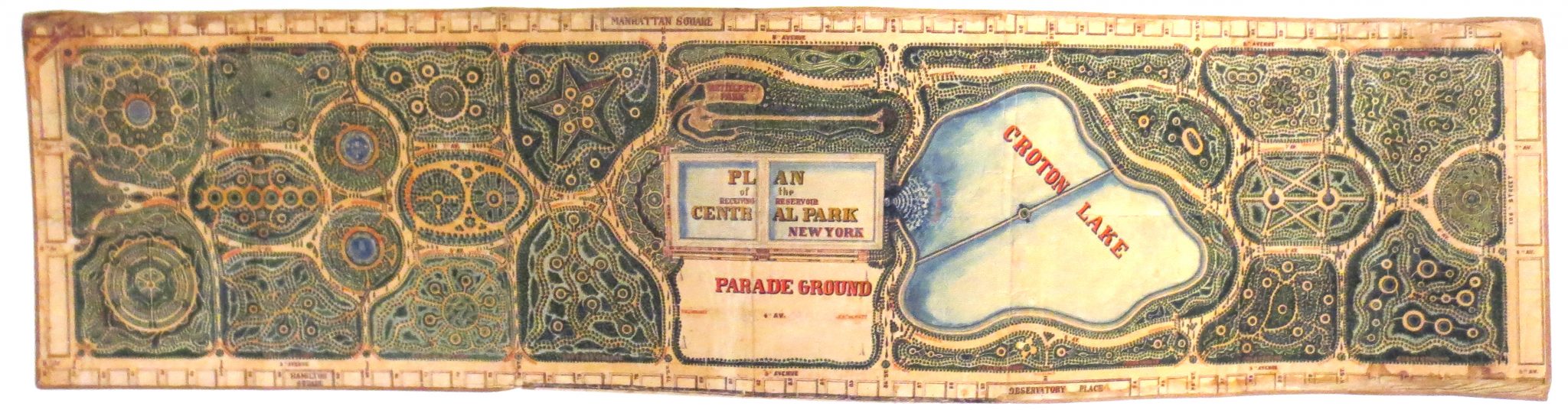

By March 1858, the deadline for the competition, a total of 35 plans were submitted to the Board of Commissioners. This is Samuel J. Gustin’s second-place entry for the design of Central Park.

George E. Waring’s entry for the design of Central Park.

The symmetry of this one is hilarious, given the wildly varied terrain of the site of Central Park.

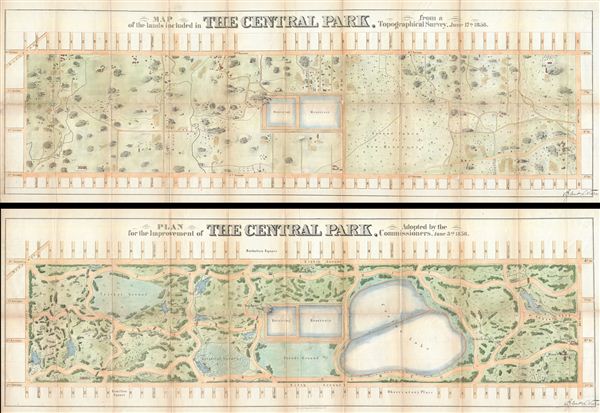

1858: The Greensward Plan

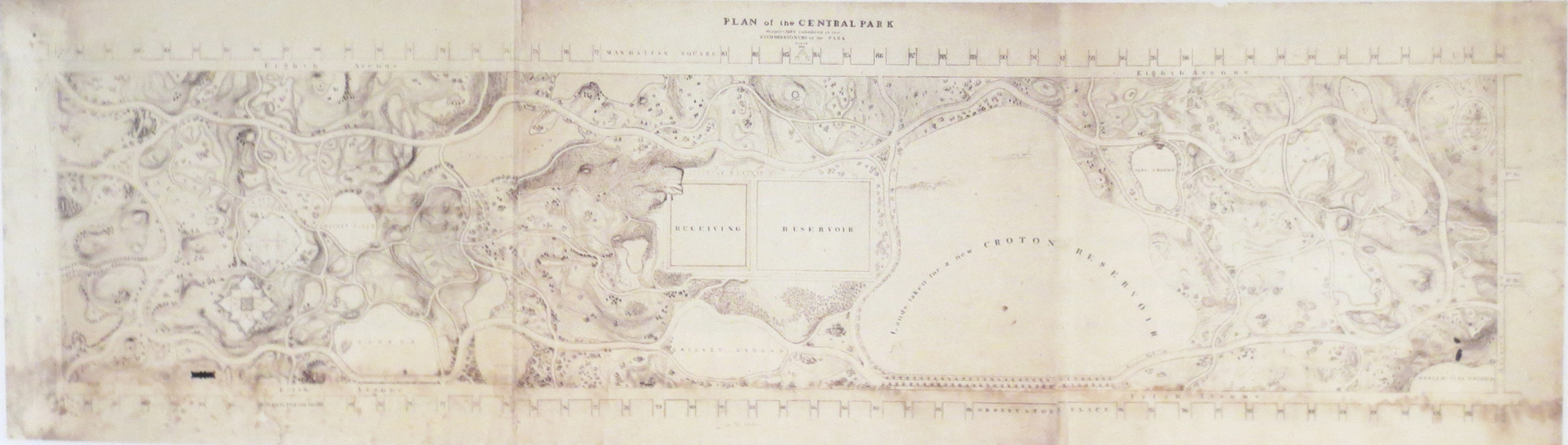

The original Greensward Plan is about 10 feet long. When I last queried the Parks Department, it was scheduled to be repaired and made available as a digital file. Until that happens, here’s a photo of it as shown in Heckscher’s Creating Central Park – an excellent book that you should definitely read if you’re interested in the early history of the Park.

The woodcut version published in the New York Times on 5/1/1858 is easier to read.

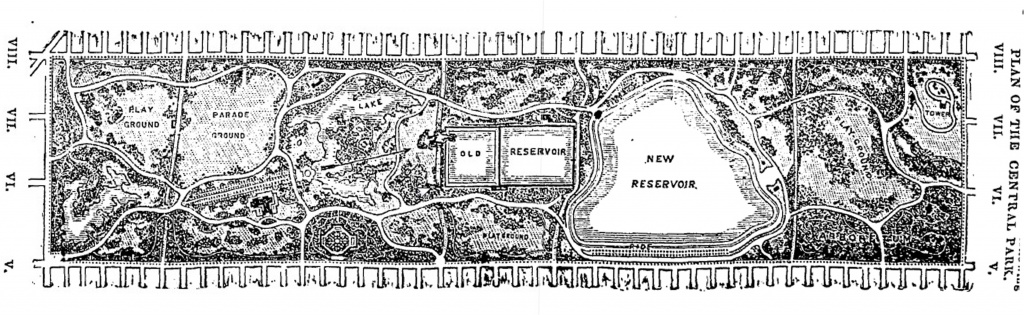

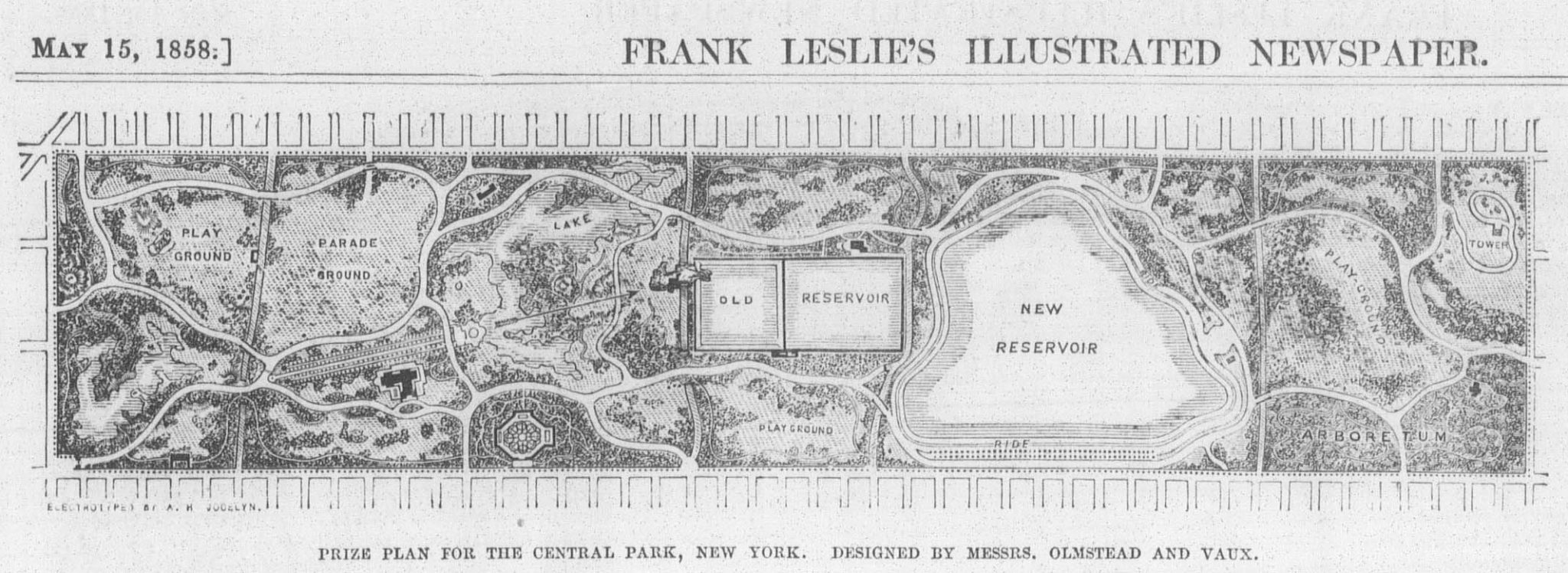

Here’s the version published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1858, and the short article that went with it.

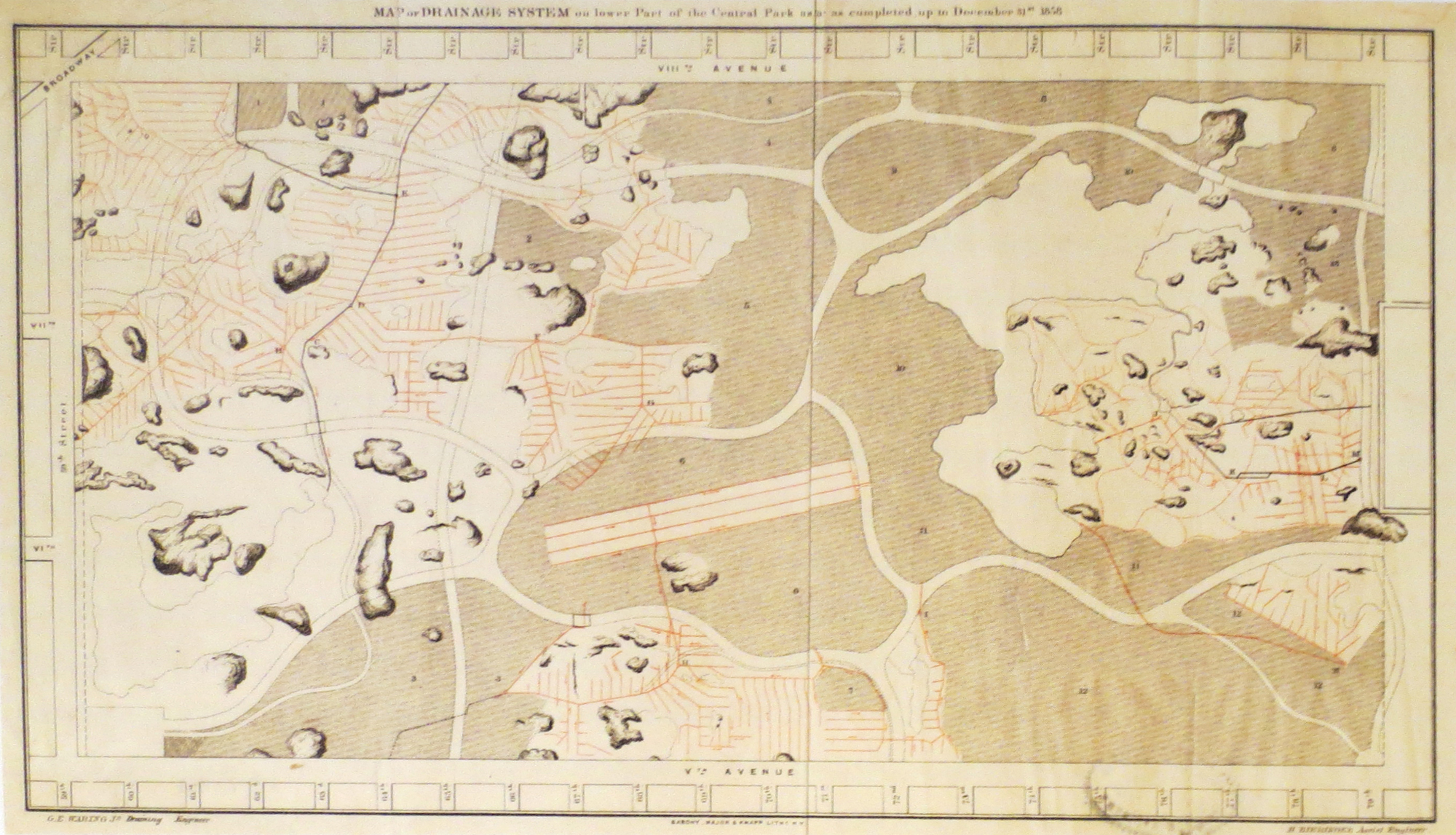

1858: work completed in the Park

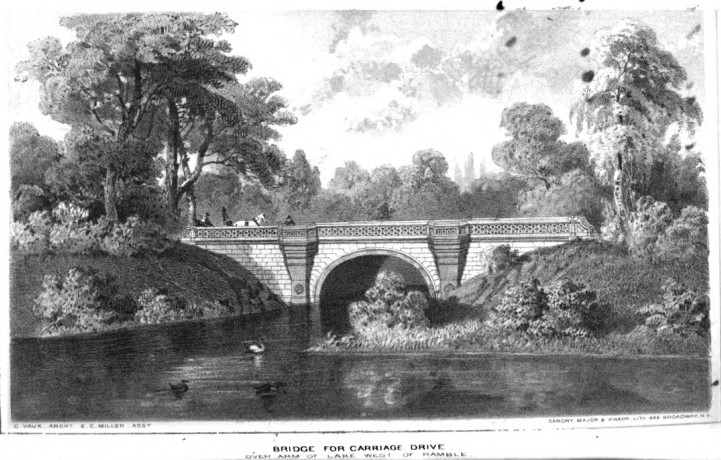

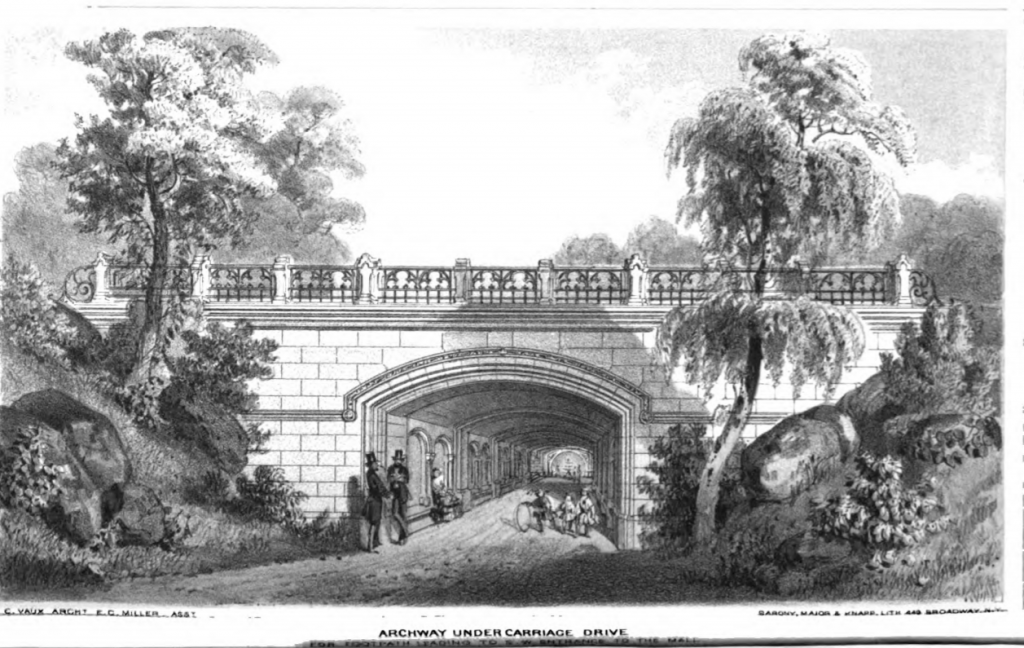

The Second Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park, covering 1858, published in 1859 (here on Google, here on the NYC Parks Dept. site) illustrated the Balcony Bridge, on the west side at 77th Street. I haven’t been able to figure out from reading the Report whether it had been constructed, or this was a proposal. I’m inclined to think it’s a proposal, since the trees and other plantings wouldn’t have been in place in 1858. When they get to the point of including photos in the annual reports … then I’m sure that the work has been finished.

View from what became Bethesda Terrace, north toward what became the Lake and the Ramble … if I’m right in assuming that tiny structure dead center is the fire tower where the Belvedere now stands. McEntee was Calvert Vaux’s brother-in-law.

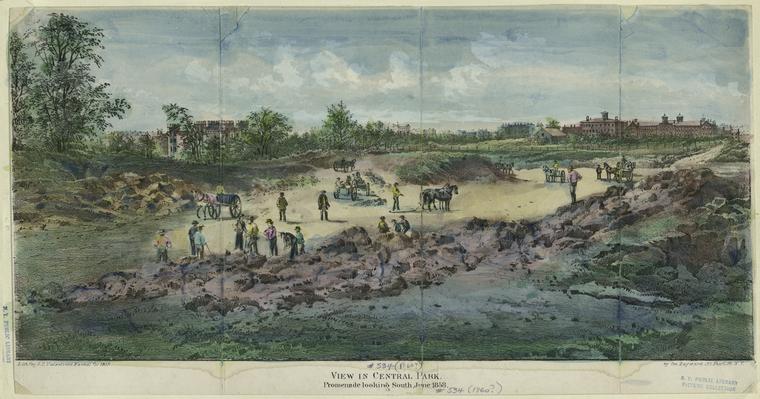

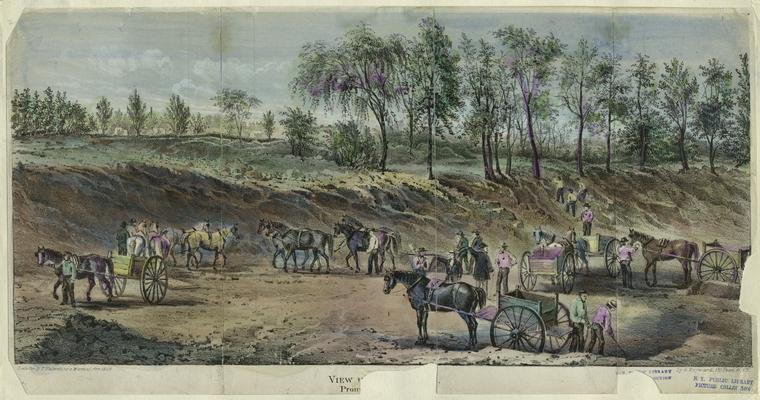

Construction in Central Park. Given the concentration of large buildings, I assume this is a view looking toward Central Park South.

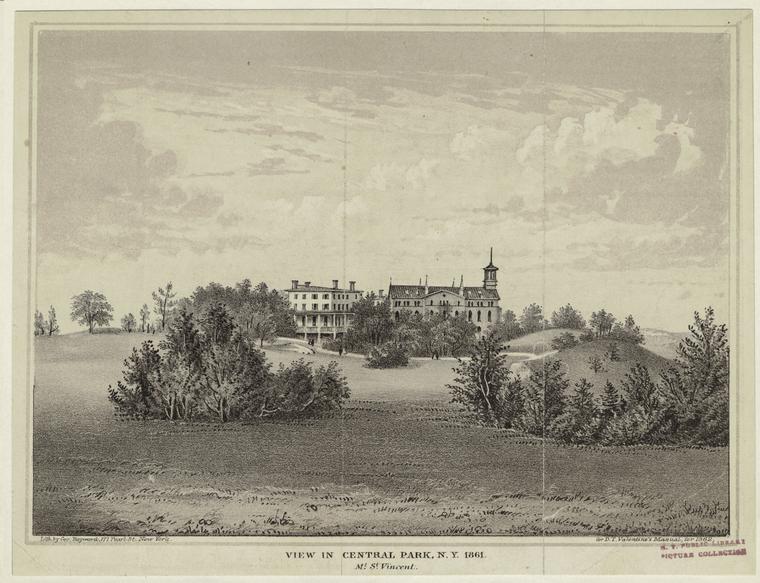

1859: Mount Saint Vincent

The Sisters of Charity of Mount Saint Vincent (est. 1846) established their motherhouse at McGowan’s Pass, roughly 103rd Street near Fifth Avenue. In 1859, after the land it sat on was taken for Central Park, the Sisters moved their home to Riverdale. The former convent was used as a restaurant and statuary gallery until it burned down in 1881. The Mount Saint Vincent Hotel (a.k.a. McGowan’s Pass Tavern) was constructed on the site in 1884 (we’ll get to that in a while) and razed in 1917: nothing of the buildings is left now but a few foundation stones. See the excellent article by Daytonian in Manhattan.

1859: Construction

The Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners for 1859 (published in 1860) included these north-south cross-sections at Sixth and Seventh Avenues. They give a vivid idea of what those constructing the Park had to deal with.

The construction of the Park was such a major event that prints of it were published. This one shows construction of the Mall (Promenade). The Arsenal is behind the trees toward the left.

1859: Maps & views

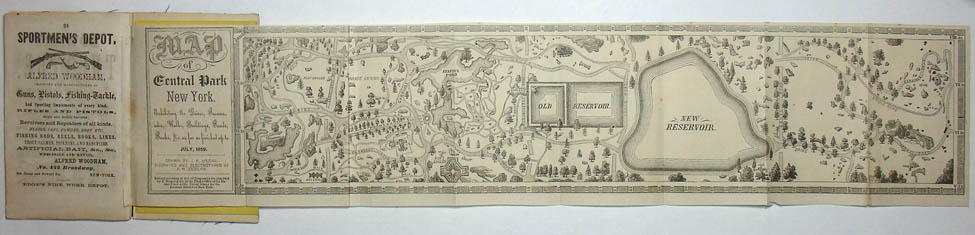

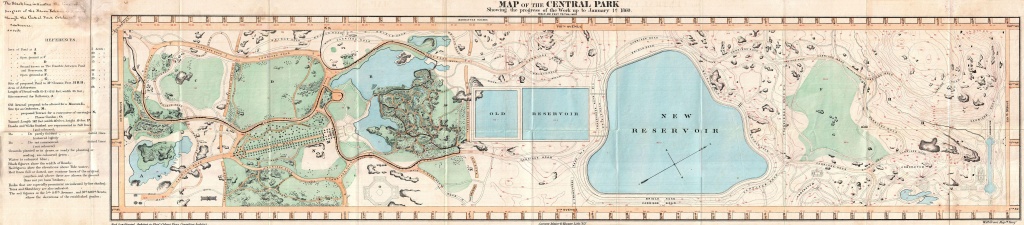

Work on the southern end of the Park was well underway by 1859, when the map below was drawn. The Extension (106th to 110th Streets) is marked off with a dotted line: the land wasn’t actually purchased until 1863. A formal garden is sketched in where Conservatory Water now stands, just north of 72nd Street. The large space between the 79th and 86th Street Transverses, and between the old reservoir and Fifth Avenue, is empty. For a while it was home to a herd of deer. In the 1870s, it was allotted to the Metropolitan Museum (more here).

Below: A Pocket Map & Visitor’s Guide to the Central Park in the City of New-York, with All the Necessary Explanations. Map by J.P. McLean, engraved by Albert H. Jocelyn, printed in New York by J. Craft and P. Burger. As of mid-September 2018, this is for sale on the George Glazer website. Regrettably, it’s not in the David Rumsey Map Collection, which makes lovely high-res images available of its holdings. (Thank you, Mr. Rumsey!)

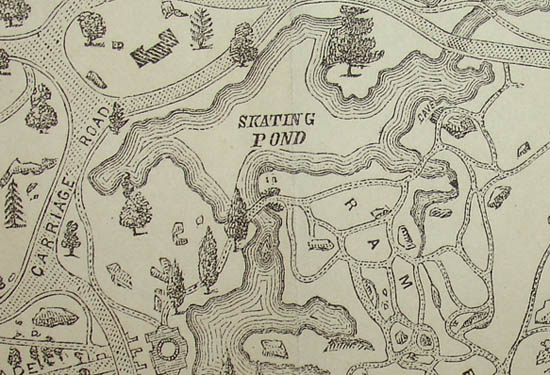

Detail of the map above, showing the Lake and Ramble.

View of Central Park in 1859, probably looking south from where the Belvedere now stands. This one with the pretty colors is via Museum of the City of New York. The Library of Congress has a high-res image of the same view, considerably faded.

1859: Bridges

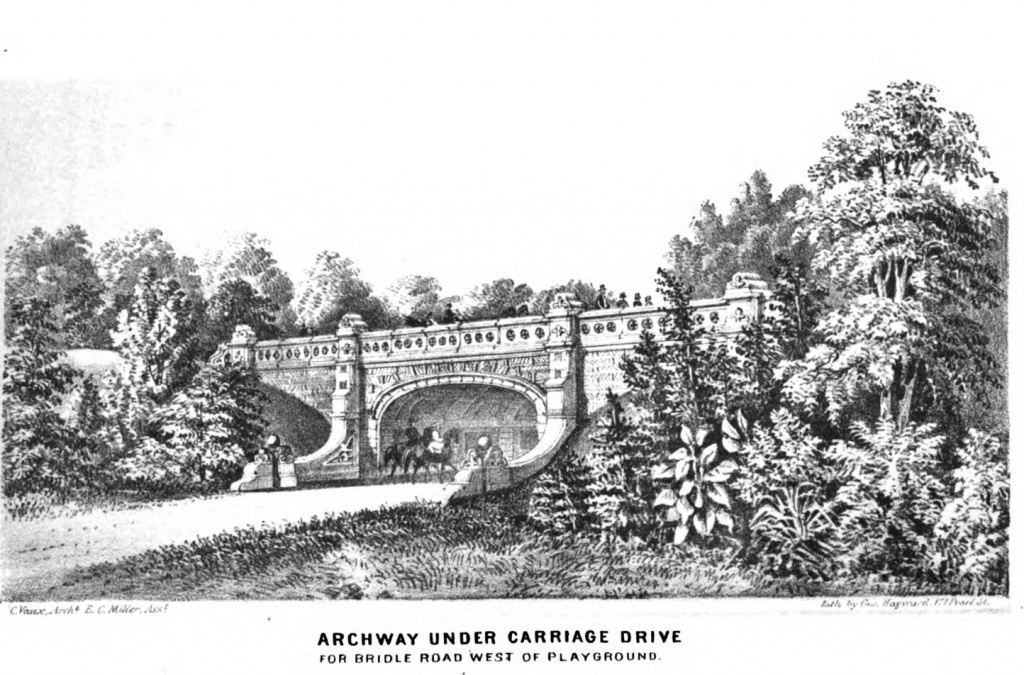

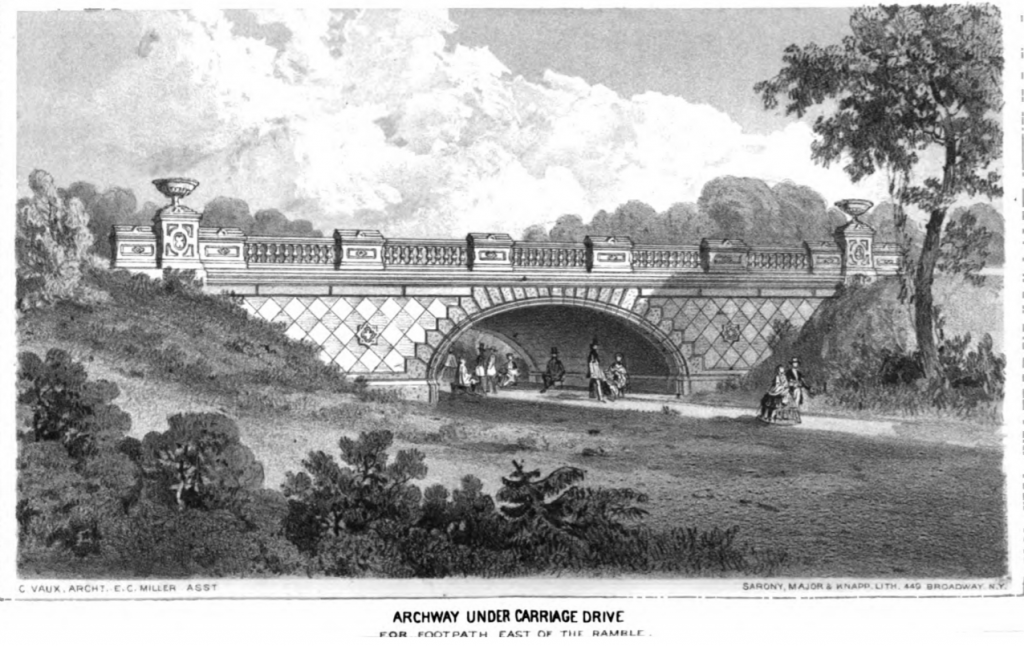

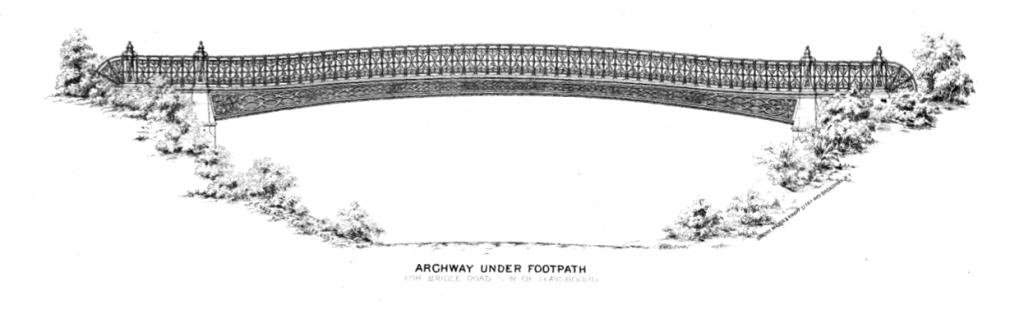

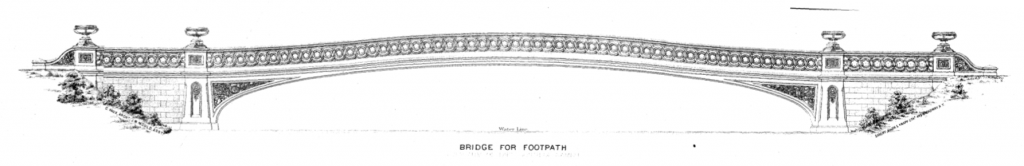

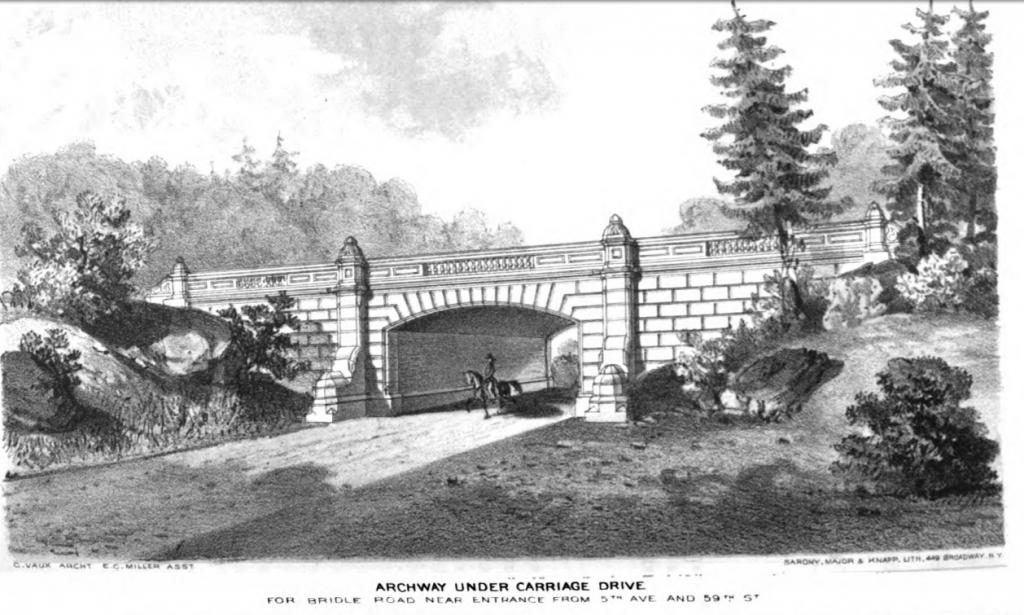

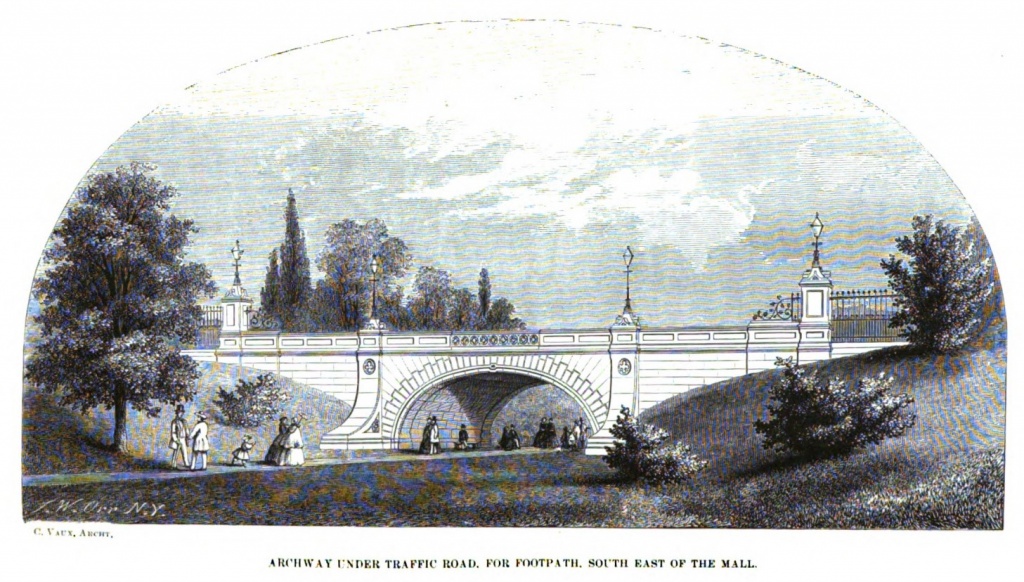

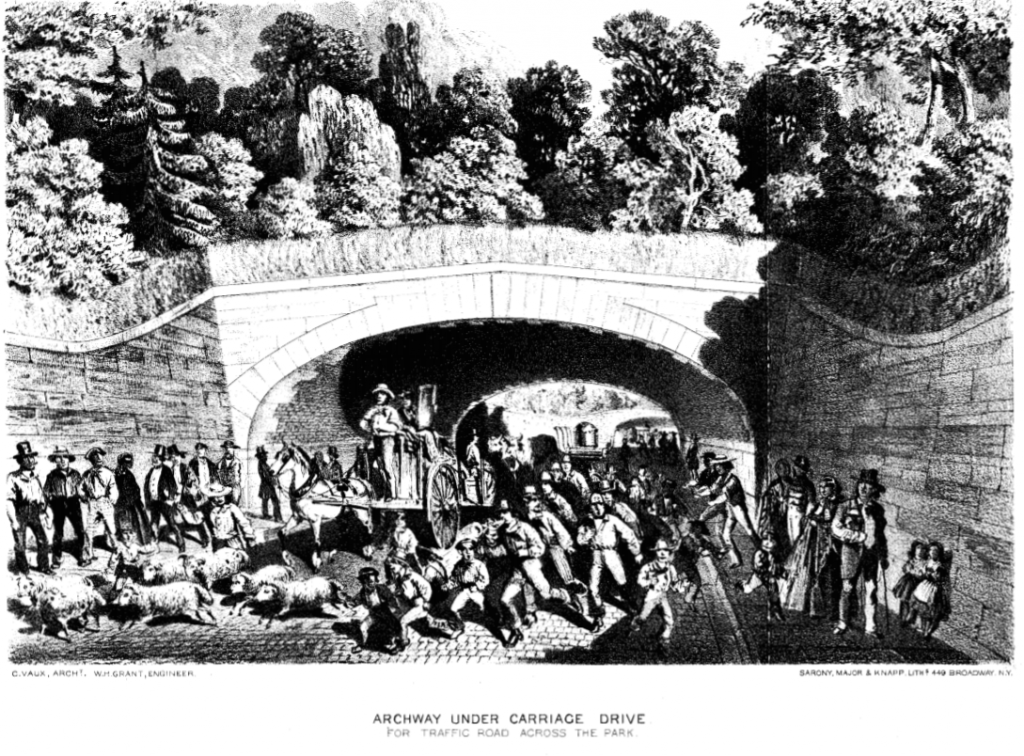

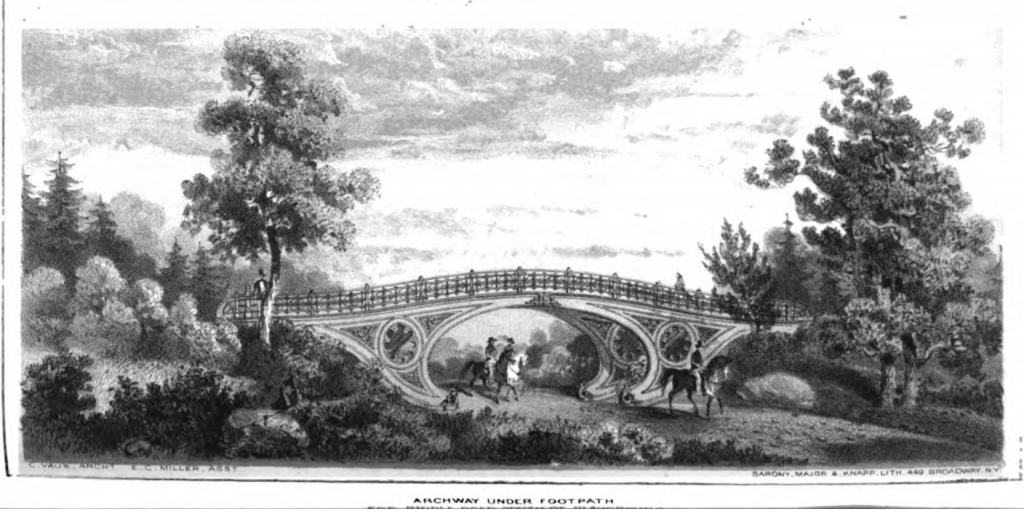

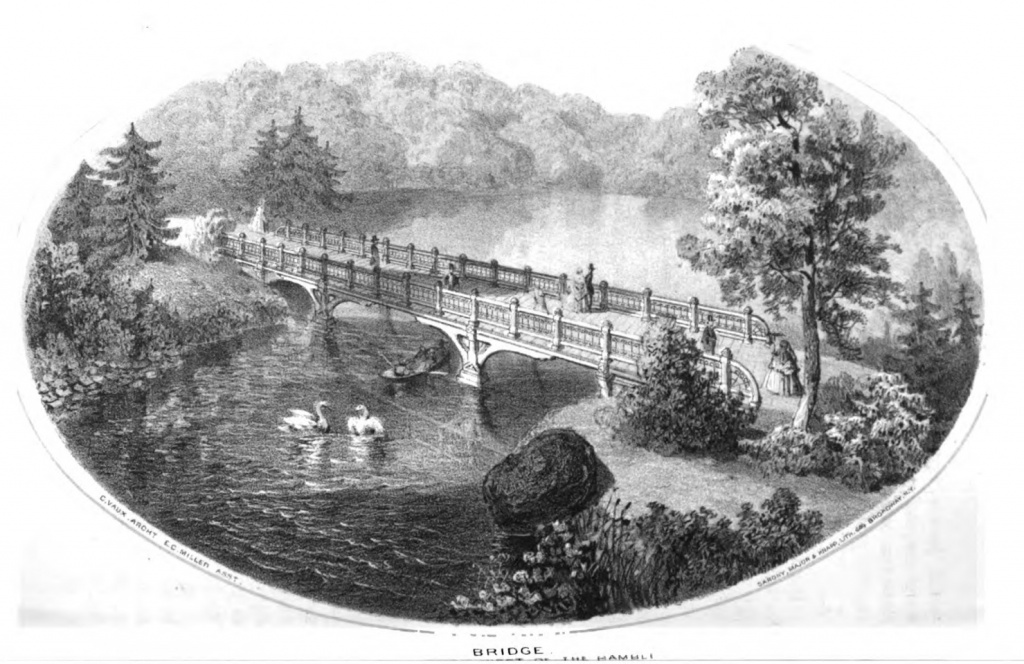

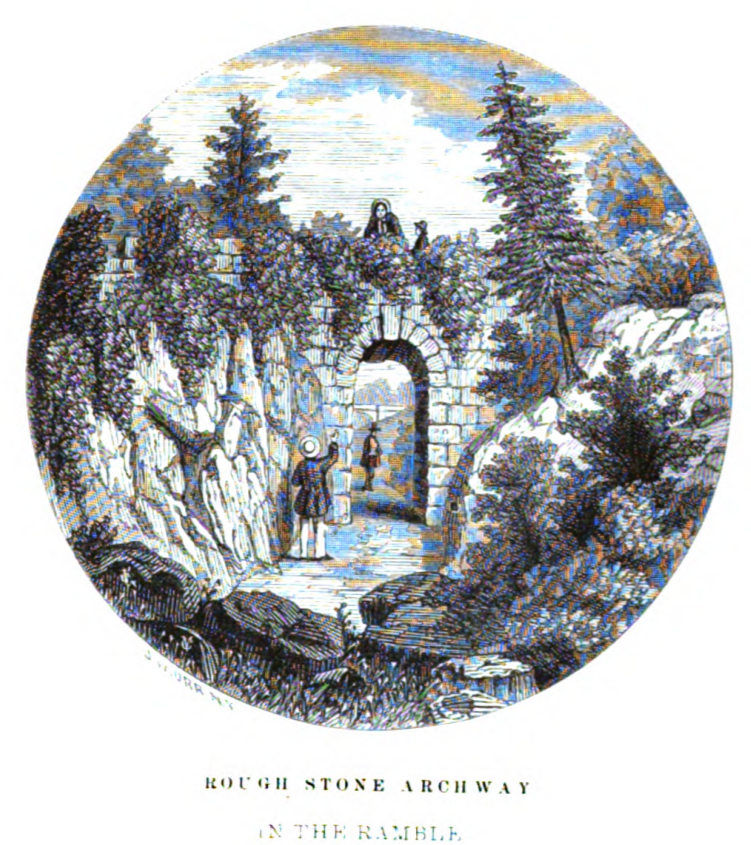

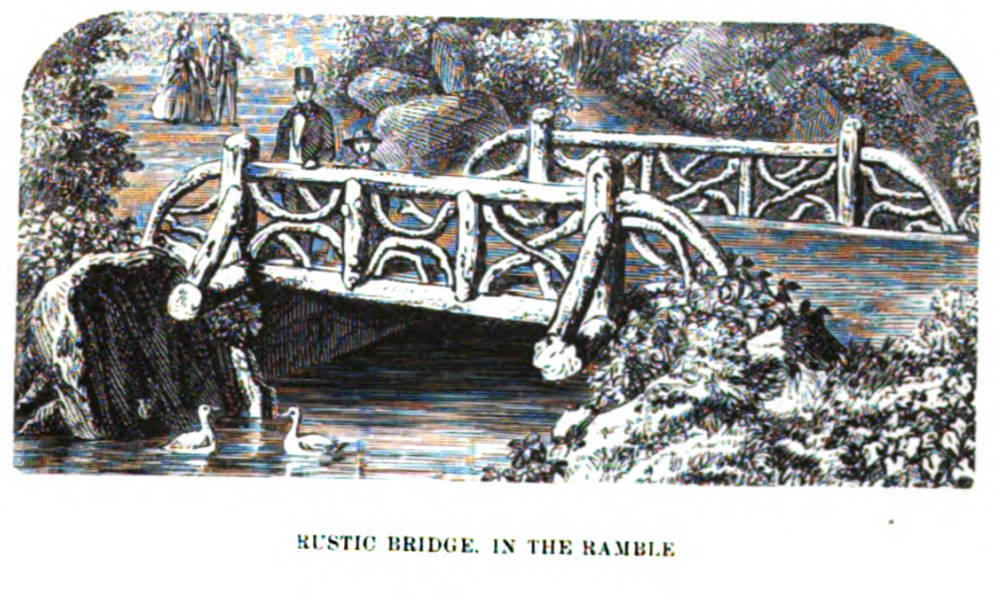

The Third Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park, covering 1859, published in 1860 (here on Google, here on the NYC Parks Dept. site) illustrated more bridges. As with the previous year’s report, these seem to be sketches of the bridges as they’ll eventually look, rather than bridges that had already been constructed. See, for example, the “Description” in the Report on p. 34.

Marble Arch separated pedestrians from vehicles at the south end of the Mall. There’s a great early pic of it in situ here. Under Robert Moses, it was smashed to bits and buried. He surely got things done, did Mr. Moses. More on Marble Arch here.

Dalehead Arch carries the West Drive over the bridle path near the present-day Heckscher Ballfields.

Glade Arch is east of the Ramble.

The cast-iron Pinebank Arch carries pedestrians over the bridle path in the southwest part of the Park.

The cast-iron Bow Bridge carries pedestrians from the area near the Mall across the Lake to the Ramble. Olmsted and Vaux, who designed the Park as a pastoral retreat, wanted visitors to take their time strolling around the Lake in order to reach the Ramble. The Board of Commissioners, however, often favored the Park as a meeting place and center of culture. They demanded a shortcut from the Mall to the Ramble. That’s why we have the elegant, cast-iron Bow Bridge (For more on the bridges added to the Greensward Plan, see Central Park: The Early Years, chapter 5.)

The Green Gap Arch carried the East Drive over the bridle path near 59th Street. The path is now closed off.

Denesmouth Arch carries the 65th Street Transverse above pedestrians, near the (much later) Zoo. According to Forgotten-NY: “It used to feature four ornate castiron lampposts, three of which were stolen; the 4th is in safekeeping somewhere.”

This is a sketch for one of the transverse roads, designed to carry commercial traffic across the Park.

You may think you recognize this one, but you don’t.

Oval Arch, in the southwest corner of the Park, separated pedestrians from the bridle path. Robert Moses demolished it in order to enlarge the playground that became the Heckscher Ballfields.

The Oak Bridge is on the west side of the Ramble, roughly at 77th Street.

Rustic Arch is also on the west side of the Ramble.

A rustic-style bridge in the Ramble.

1859: Bethesda Terrace

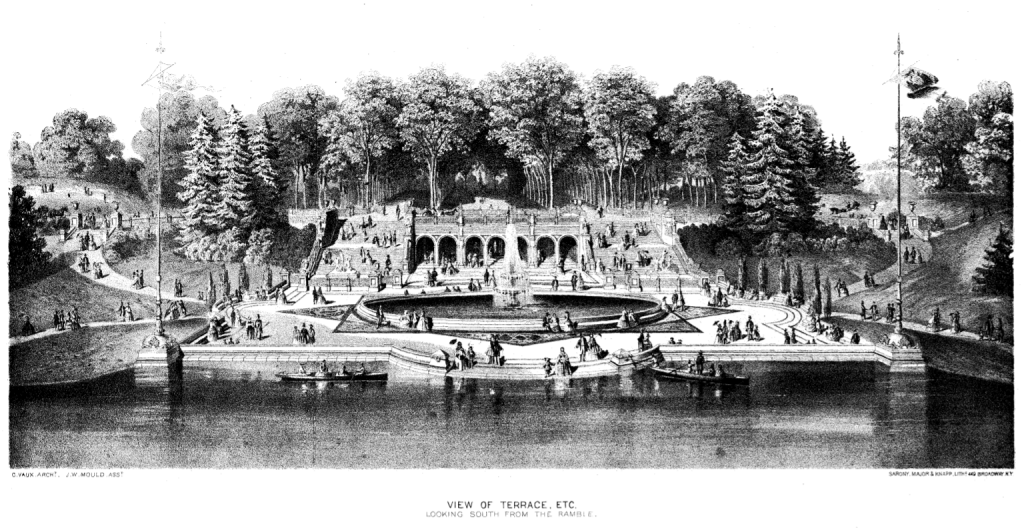

This illustration from the report of the Board of Commissioners for 1859 shows Bethesda Terrace (still under construction in 1862) with a simple fountain on the site of the future Angel of the Waters (dedicated in 1873). The illustration is signed by Jacob Wrey Mould, who was responsible for many of the ornamental details in Central Park.

Bethesda Terrace, viewed from across the Lake.

1859: The Park’s first sculpture

By 1855, New York had a thriving population of German immigrants: only Berlin and Vienna had larger German-speaking populations. Among the events in New York celebrating the centennial of Friedrich Schiller’s birth was the dedication of this sculpture. But sculptures didn’t quite fit the pastoral vibe that Olmsted and Vaux were trying to create in the park; they tucked Schiller away in the Ramble. It has only been in its present site, near Beethoven and the Naumburg Bandshell, since 1955.

1860: Maps & Views

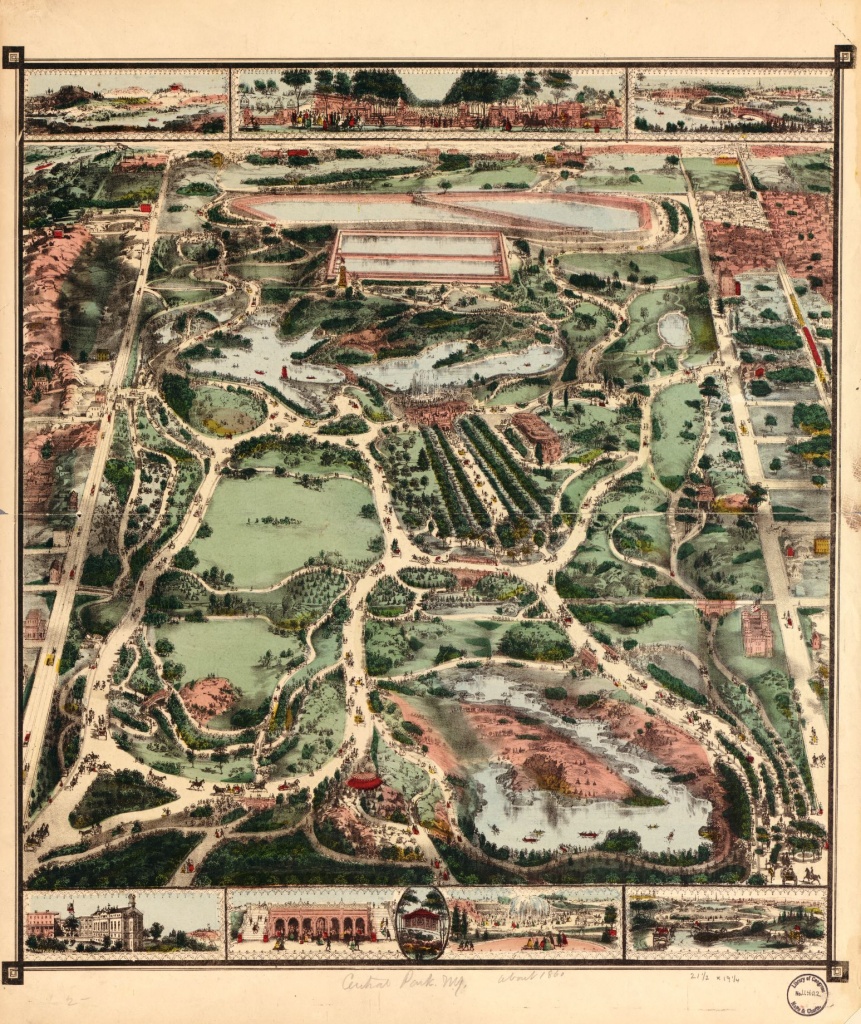

Below: a view of Central Park that Library of Congress dates to 1860. NOTE: Either the date is wrong, or the artist was doing a lot of wishful thinking. The Casino (northeast of the Mall) was still on the drawing board in 1863, and Bethesda Terrace was still under construction when Prevost photographed it in 1862. Vignettes at the top of this view: the Lake, the north end of the Mall, and the Lake with the Bow Bridge. Vignettes at the foot: Mount St. Vincent, Bethesda Terrace, Rustic shelter (in oval), Bethesda Fountain, and view south from Lake.

View south to the firetower (soon to be replaced by the Belvedere) and the Lake.

1860: South end of the Park

Shanties in Central Park. NYPL gives the date of the photo as ca. 1860; it certainly can’t have been taken much later, since the shanties were removed fairly early in construction.

View of the Ramble ca. 1860, according to New York Public Library. Is that the Ramble Arch in the middle distance? If so, the hill in the foreground is hiding a lot of its height.

1860: North end

The Blockhouse: according to the Bowery Boys website, 1860.

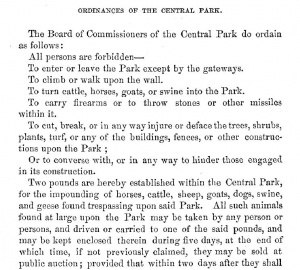

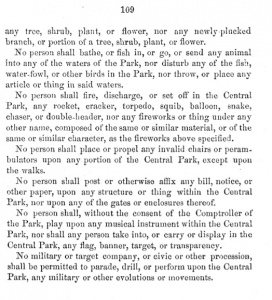

1860: Ordinances

In their Fourth Annual Report (1860, published in January 1861), the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park set out 4 pages of rules and regulations for the Park that give a vivid image of what was going on in the Park in its early years. For example, so many stray animals were captured and put in the Park’s pound that a minimum price for the sale of horses, dogs, goats, swine, sheep and geese was set. The Board also had strong words to say about fireworks, fortune-telling, perambulators … Who’d have suspected our ancestors of such shenanigans?

The Fourth Annual Report has no illustrations.

More

- This page is a work in progress: bookmark it, or follow me on Twitter @NYCsculpture to be notified when new images are added.

- Central Park: The Early Years covers Central Park from the 1850s to 1870s. Details here, or order on Amazon here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.