This essay is adapted from Chapter 6 of Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. I’ve kept cross-references to other chapters in the book, all of which will eventually be updated and posted on this site. Click on “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan book” in the Obsessions cloud at lower right to see which are already here.

- Sculptor: John Quincy Adams Ward. Granite pedestal by Richard Morris Hunt.

- Dedicated: 1883.

- Medium and size: Bronze (12 feet), granite pedestal (approximately 11.5 feet at front).

- Location: Wall and Nassau Streets, Federal Hall National Memorial. Subway: 4, 5 to Wall Street

About the sculpture: Why the Roman imagery?

Washington took the oath of office, kissed the Bible, and then (the moment shown here) turned to acknowledge cheering onlookers. You can and should consider the significance of the position of his head (tilted up? down? level?), the direction of his gaze (what if he were looking down his nose?), the expression of his mouth (picture him with a big grin—I dare you), and the gesture of his hand. But right now, look at the pillar behind Washington on which the Bible rests.

The bundle of rods tied together with bands is a fasces, a symbol carried by escorts of Roman magistrates from at least the fifth century B.C. as a reminder of the magistrates’ power to punish. Omitted in this sculpture is the axe for decapitating lawbreakers that protruded from the bundle’s center.

In this statue, Washington also wears a cape whose lush folds recall a Roman toga.

Why are two ancient Roman elements included so prominently in Ward’s sculpture of an American president? Why do similar ancient elements also appear in the Statue of Liberty, the Washington Arch (Outdoor Monuments Chapters 1 and 12), and other Manhattan sculptures?

Back in 800 A.D., more than three centuries after the Roman Empire in the West collapsed, Charlemagne had himself crowned Holy Roman Emperor. The territory he ruled was mostly in France and Germany, but the mere use of the title “Roman Emperor” linked Charlemagne with one of one of the world’s most powerful and longest-enduring civilizations.

In fact, whenever a medieval or Renaissance ruler wanted to enhance his prestige, he turned to the classical style: the imagery of the Romans and of the Greeks, from whom the Romans adapted much of their art. In France, where the Statue of Liberty was made, a revival of the classical style had begun in the late 1700s. Nineteenth-century American sculptors trained in Europe brought the neoclassical style to the United States. Its influence is obvious in several sculptures in Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan.

The fasces and the toga/cloak don’t give Washington dignity: that comes from his posture, expression and gesture. But the classical elements do, by association, give him an extra ounce of authority, and suggest that he’s one of a long line of distinguished rulers, rather than the first elected executive of a nation that had been independent barely a dozen years.

About the subject: Washington’s inauguration

For over a century, history has usually been presented as an inevitable, predetermined march of events. Event A happened, and because of that Event B, and then of course Event C. Individuals are viewed as irrelevant in this inexorable progression.

But history comes alive only if we remember that the individuals of a given period had their own values, purposes and goals, and had no knowledge whatsoever of what was to come. To make history come alive, we have only to ask: What was important to those people? What events within their lifetimes colored the way they thought? Why did they make the choices they did, and what other possibilities did they reject?

Looked at from this perspective, even the unadorned American-made suit Washington wore at his first inauguration (which Ward has reproduced in this sculpture) is significant.

On April 30, 1789, most of those crowding the streets and rooftops to watch Washington take the Oath of Office as first president of the United States had lived through seven grueling years of war against one of the world’s superpowers. They had suffered under the weak government established by the Articles of Confederation. Then, during five months of bitter wrangling in 1787, forty-three delegates in Philadelphia had hammered out a document setting forth the principles on which the government of the United States would operate. (See Chapter 12 in Outdoor Monuments, on the Washington Arch, for Washington’s role there.)

Even with brilliant promotion by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison in the Federalist Papers, it was nine months before the Constitution gained enough votes to become binding. Five states signed only on condition that a Bill of Rights be added, which it had not been by April 1789. The day Washington took the Oath, Vermont, Rhode Island and North Carolina had not even ratified the Constitution. (On the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers, and the ratification process, see the 52nd through 58th in my series of essays on Alexander Hamilton, starting here.)

The difficulties faced by the new nation were obvious. The United States’ large territory held a diverse and notoriously independent population: see Washington Irving’s comments in the next section. The new government was deeply in debt, with no established source of income. (See Hamilton, Chapter 53 in Outdoor Monuments; and the 59th through 62nd in my series of essays on Hamilton, starting here.)

Washington himself—America’s greatest Revolutionary War hero—was potentially a problem. No other man was even conceivable as the first president; he was unanimously chosen by the Electoral College. Yet Washington’s every action was scrutinized for evidence of a lurking desire to become a monarch or dictator.

For the spectators who watched Washington as he stood on the second-floor balcony in Federal Hall, at Wall and Broad Streets, on that spring morning, it was no minor matter that Washington wore a plain coat of American make. Had he worn velvet, silk and jewels, like European royalty, it would have confirmed some viewers’ worst suspicions. Then even Washington’s reputation might not have been enough to hold the country together through his term as president.

Irving on George Washington’s Inauguration, April 30, 1789

Inexperienced in the duties of civil administration, [Washington] was to inaugurate a new and untried system of government composed of States and people, as yet a mere experiment, to which some looked forward with buoyant confidence, many with doubt and apprehension.

He had moreover a high-spirited people to manage, in whom a jealous passion for freedom and independence had been strengthened by war and who might bear with impatience even the restraints of self-imposed government. . . .

[The country] presented to the Atlantic a front of fifteen hundred miles divided into individual States differing in the forms of their local governments, differing from each other in interests, in territorial magnitudes, in amount of population, in manners, soils, climates and productions, and the characteristics of their several peoples. Beyond the Alleghenies extended regions almost boundless, as yet for the most part wild and uncultivated, the asylum of roving Indians and restless, discontented white men. — Washington Irving, Life of George Washington, 1855-59

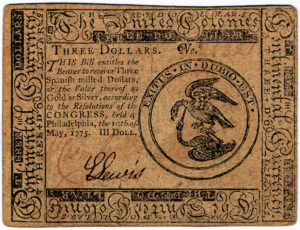

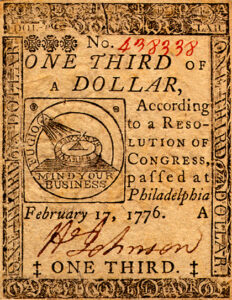

Continental Currency

Above: Continental currency from the Revolutionary War, with the depressing motto Exitus in dubio est: “The outcome is far from certain.” (What are those birds doing to each other?) On the disastrous state of American finances immediately following the Revolutionary War, see Hamilton in Central Park.

Above: Continental currency with a more cheerful slogan: “Mind your business.” The sundial and the word “fugio” refer to “Tempus fugit” (Time flies).

John Quincy Adams Ward

John Quincy Adams Ward (b. Urbana, Ohio, 1830, d. New York City, 1910) worked with Henry Kirke Brown on the Washington at Union Square, dedicated in 1856 (Outdoor Monuments Chapter 13). Far earlier than his contemporaries, Ward believed American sculptors should present American ideas and be trained in America: he never studied abroad. For fifty-odd years, he was known as the “Dean of American Sculpture.” Indian Hunter, 1869 (Central Park, near the Mall), established his reputation. Manhattan has Washington, Greeley, Holley, Conkling, Dodge and Shakespeare (Outdoor Monuments Chapters 6, 7, 11, 18, 24, 37), as well as the Seventh Regiment Memorial,1869 (Central Park, West Drive at 67th Street), and the Pilgrim, 1885 (Central Park, east end of the 72nd-Street Traverse). The original sculptures of the New York Stock Exchange pediment were Ward’s, but they’ve been replaced with copies. Brooklyn has Henry Ward Beecher, 1891 (Columbus Park).

Ward and Contemporary Art

Ward died in 1910, when Rodin and “modern art” such as that shown at the Armory Show in 1913 were becoming more popular. (See Butterfield and Theodore Roosevelt on the Armory Show.)

Frank Jewett Mather, Jr., seems to have had such works in mind when he commented:

Such an art presupposes discipline, clearness of aim, self-knowledge on the part of its creator. It is not my purpose to appraise Ward’s singularly even and meritorious production. It seems to me to have a high and especial value in view of prevailing notions that hysteria and the artistic temperament are convertible terms. Ward’s life and purposeful well-balanced work are an effective protest against the fallacy that the life artistic ranges between overt melodrama and inward tragedy. — “Address of Frank Jewett Mather, Jr.,” John Quincy Adams Ward, Memorial Addresses Delivered Before the Century Association, Nov. 5, 1910(1911), pp. 5-6

Commenting on Ward’s Washington, sculptor Lorado Taftnoted that Ward was not attempting to convey a naturalistic portrait, and that the finished work is the better for it.

Foremost among the many interpretations [of Washington in sculpture], according to not a few good judges, including prominent members of the profession, stands this noble figure by Mr. Ward. A realistic treatment of the subject was by no means desirable. Houdon gave us this, combined with a mastery of curious skill. Mr. Ward shows us not the intimate, domestic Washington of Mount Vernon, nor even the actual – shall we say casual? – man seen by the few who stood nearest the inaugural, but the great, legendary figure toward whom the whole country turned in those days, and whom the years have further consecrated, glorifying even as they veil. If our very friends are largely the product of our imaginations, how much more is a great public character but a symbol on which to hang the attributes of our likes or our dislikes! We owe thanks to Mr. Ward for such a “symbol.” This quiet, impressive figure, supported by the fasces and enriched by the sweep of the great military cloak, lifts its hand in the simple gesture which betokens authority guided by moderation and intelligence. It has in it the essentials of Washington, while the peculiarities, real or imaginary, are left out. The statue is the greater for the well-weighed omission. — Lorado Taft, History of American Sculpture (1903), pp. 225-6

More

- My favorite short biography of George Washington is Paul Johnson’s George Washington: The Founding Father (Eminent Lives series). Johnson (a Brit) puts Washington and the American Revolution into a worldwide context, which few American historians do. For a long quote from Johnson on Washington’s staff during the Revolutionary War, and for substantial quotes from Washington, see the 16th in my series of blog posts on Alexander Hamilton. The posts are available in print as a two-volume set: details here.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.