This essay is adapted from Chapter 2 of Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. I’ve kept cross-references to other chapters in the book, all of which will eventually be updated and posted on this site. Click on “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan book” in the Obsessions cloud at lower right to see which are already here.

- Sculptor: Jonathan Scott Hartley.

- Dedicated: 1903.

- Medium and size: Bronze (10 feet), on a granite pedestal (11 feet) that bears four bronze reliefs (each 12 x 27.5 inches).

- Location: East side of Battery Park, State Street at Bridge Street, just south of the U.S. Customs House.

About the sculpture

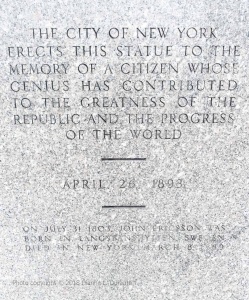

When Ericsson was unveiled in 1893 to a twenty-one-gun salute and a lengthy parade, New Yorkers saw a man standing languidly, gesturing with a compass in his right hand to a small square of paper in his left. It didn’t look like the gruff old man who for decades had been a familiar figure in New York, and whose ironclad Monitor had saved New Yorkers, they believed, from a Confederate naval attack.

The sculptor, Hartley, was so dissatisfied with that statue that he had a revised one cast at his own expense. Rededicated with another twenty-one-gun salute in 1903, Ericsson now stands tall and confident, with stern mouth and frowning brow. In one hand is a roll of blueprints, in the other a model of the Monitor.

Reliefs on the pedestal commemorate several of Ericsson’s inventions. On the front is the USS Princeton, America’s first screw-propelled vessel of war, still bearing the masts and rigging of a sailing vessel.

On Ericsson’s left, the Monitor battles the Merrimac.

Behind him are a rotary gun carriage and other inventions.

To Ericsson’s right, firemen battle a raging blaze using the steam-driven fire engine for which he won a prize in 1840 – an era when flames sometimes destroyed hundreds of New York City buildings within a few hours. (See Firemen’s Memorial, Outdoor Monuments Chapter 45.)

Portraits are meant to remind us of great deeds and great minds—of what the best among us have accomplished and of the heights to which each of us can aspire. To achieve this purpose, a portraitist must be selective. The statue must convey a strong physical resemblance, but must also show the sitter in a characteristic attitude, one that evokes the sitter’s personality and accomplishments. This second version of Ericsson fulfills that requirement. The first did not.

About the subject

On January 30, 1862, the day of the Monitor’s launch, New Yorkers crowded the shores of the East River to witness a disaster. The ship was constructed mostly of iron: how could she possibly float? Thomas Rowland, one of Ericsson’s builders, recalled:

It was the opinion of most shipbuilders that she would ‘throw pitch pole’—that is to say, her stern would go immediately down into the mud at the bottom of the river and she would turn a somersault. But her peculiarities I had provided for by putting air tanks under her stern and by an automatic device allowing the air to escape and the water to run into those tanks just in proportion as the vessel should be immersed in the water while leaving the ways. She was enabled thereby to slide into the water as quietly as a duck going into a pond to swim. — “The Monitor’s Builder. Thomas F. Rowland Tells How He Worked for Ericsson,” New York Times 9/14/1890

Why was this floating tin can built? The nineteenth century had seen rapid innovations in naval warfare. In the 1810s came the introduction of steam-powered ships—much faster and more maneuverable than sailing ships. Soon afterwards came artillery shells that could destroy a steamboat’s paddlewheel and leave her dead in the water.

Ericsson (1803-1889), a Swedish-born engineer working in England, was invited to the United States in the 1840s to design and oversee the building of a screw-propelled warship, because its underwater propulsion system would be a much more difficult target. During trials, the screw propellers of the USS Princeton functioned perfectly … but a gun designed by a colleague exploded, killing the secretary of the navy, the secretary of state, and President Tyler’s prospective father-in-law. (See the Currier and Ives illustration here: not their usual comforting and cheerful style!) Ericsson’s relations with the Navy were arctic for the next twenty years, and might have remained so had the Civil War not intervened.

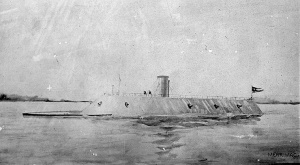

In late 1861, the North learned that a Confederate ironclad would soon be ready to devastate the Union’s port cities. The Confederacy had raised the frigate Merrimac from Norfolk harbor, christened it the CSS Virginia, and iron-plated the charred hulk. Although she sailed lopsidedly and had barely functional engines, the Virginia was among the most powerful warships afloat because she could withstand shelling indefinitely while mercilessly bombarding her opponents.

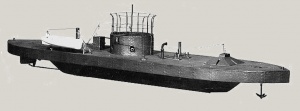

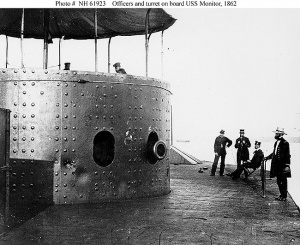

The Navy urgently invited proposals for a Union ironclad. Ericsson submitted a design for a radically different type of warship: small and maneuverable, with two powerful guns in a rotating turret, a low, stable design, and propeller and engines tucked below the waterline. After an exchange of acerbic comments with the Navy Board, he won the contract. Returning to New York, he oversaw the building of the Monitor in a hundred days flat—in the dead of winter, at a time when no bridges or tunnels existed for rapid transportation between the shipyards in Manhattan and in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

In early March 1862, as the Monitor wallowed southward through heavy seas, the telegraph flashed the news to New York and Washington that the Merrimac, on her maiden run from Norfolk, had rammed and sunk a fifty-gun Union frigate, set another on fire, and run a third aground. In a single day’s battle, the Confederacy suddenly had the chance to break the Union blockade and become an international sea power.

George Templeton Strong, whose Diary offers a fascinating eyewitness view of this period, wrote:

Sunday came the . . . disastrous tidings that the Merrimac was on the rampage among our frigates in Hampton Roads, smiting them down like a mailed robber-baron among naked peasants. General dismay. What next? Why should not this invulnerable marine demon breach the walls of Fortress Monroe, raise the blockade, and destroy New York and Boston? And are we yet quite sure that she cannot? The nonfeasance of the Navy Department and of Congress in leaving us unprotected by ships of the same class, after ample time and abundant warning, is denounced by everyone. — George Templeton Strong, Diary, 2/27/1862

Terrified New Yorkers instructed the Common Council to appropriate the enormous sum of $500,000 for harbor defenses, “at any sacrifice and at every hazard.”

The Battle of the Ironclads on March 9, 1862, is one of the most familiar stories of the Civil War. Although both ships steamed away largely unscathed after a four-hour battle, in the long term the Union won. The blockade remained intact, and the Merrimac was bottled up at Hampton Roads.

Although Ericsson’s Monitor went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras later in 1862, her effect on naval warfare was profound. The British Navy—the most formidable in the world—cancelled all outstanding orders for wooden sailing ships. Iron plating, rotating turrets, steam power and screw propellers were to be the characteristics of the warship of the future.

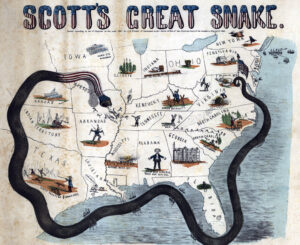

Scott’s Anaconda

Above: Like many 19th-century political cartoons, this one created in 1861 to show General Winfield Scott’s blockade of the South is remarkable for the amount of commentary it packs into a small space. Kentucky: “Armed Nutrality [sic].” Alabama: “Dam old Virginia took our capitol!” Maryland: “We give in!”

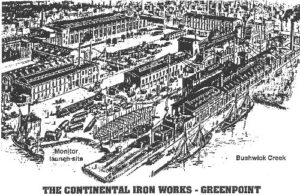

Construction of the Monitor

One of the sites of the Monitor’s construction in 1861-1862 was the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, an area now famous for its hip night-life rather than its industry. The ironworks was at the west end of Calyer Street.

The story of the design and construction of the Monitor and its battle with the Merrimac is told in detail, profusely illustrated, in the opening segment of From Portraits to Puddles: New York Memorials from the Civil War to the World Trade Center Memorial (Reflecting Absence).

We Need an Ironclad!

During the Civil War, news of battles was relayed almost instantaneously by telegraph and then newspapers. (See Sherman on journalistic progress and peccadilloes.) George Templeton Strong, a lawyer in New York, wrote on February 27, 1862:

Sunday came the news that Banks had occupied Leesburg, and a few minutes later the disastrous tidings that the Merrimac was on the rampage among our frigates in Hampton Roads, smiting them down like a mailed robber-baron among naked peasants. General dismay. What next? Why should not this invulnerable marine demon breach the walls of Fortress Monroe, raise the blockade, and destroy New York and Boston? And are we yet quite sure that she cannot? The nonfeasance of the Navy Department and of Congress in leaving us unprotected by ships of the same class, after ample time and abundant warning, is denounced by everyone.

Later in same entry:

Tea at Professor Cache’s, where were [Edwin] Stevens of the Hoboken Battery and Professor [Joseph] Henry of the Smithsonian. Our talk was of floating batteries and mail-clad steamers, and of the maximum time needed to finish the Stevens battery. … Eliot and Dr. Jenkins met me with news of the advent of the Ericsson, sicut deus ex machina, and that the Merrimac, new-baptized the Virginia, is beat back to her den, more or less damaged. – George Templeton Strong, Diary, 3:209-10 (entry for 2/27/1862)

…And the Remains of the Monitor

The Monitor foundered in a storm off Cape Hatteras late in 1862, less than a year after she had been launched. In 1973 marine archeologists located the wreck of the Monitor, which is slowly being refurbished for display in the Mariners’ Museum at Newport News, Virginia.

More

- Jonathan Scott Hartley (1845-1912) was born in Albany, N.Y., and trained with Erastus Dow Palmer and in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome. He was famous for his busts, including Edwin Booth, Susan B. Anthony, and William Cullen Bryant. His series of eminent American writers appears on the façade of the Library of Congress. Manhattan has Ericsson as well as Alfred the Great on the Appellate Court, ca. 1900 (Madison Avenue at 25th Street). The Bronx has the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Memorial, 1906 (Van Cortlandt Park).

- Re the steam-power-driven fire engine on the Ericsson’s pedestal, see the essay in Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan on the Firemen’s Memorial, which discusses firefighting in New York.

- Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, who disliked ironclads, nevertheless used them effectively at the Battle of Mobile Bay.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and recurring support: details here.