- Sculptors: Hermon MacNeil (Washington as commander-in-chief) and Alexander Stirling Calder (Washington as civilian). Architect: Stanford White.

- Dedicated: Arch 1895, MacNeil’s Washington 1916, Calder’s 1918.

Medium and size: Marble, overall 77 x 62 feet. Each Washington is 16 feet. - Location: Washington Square Park, Fifth Avenue at Washington Square North.

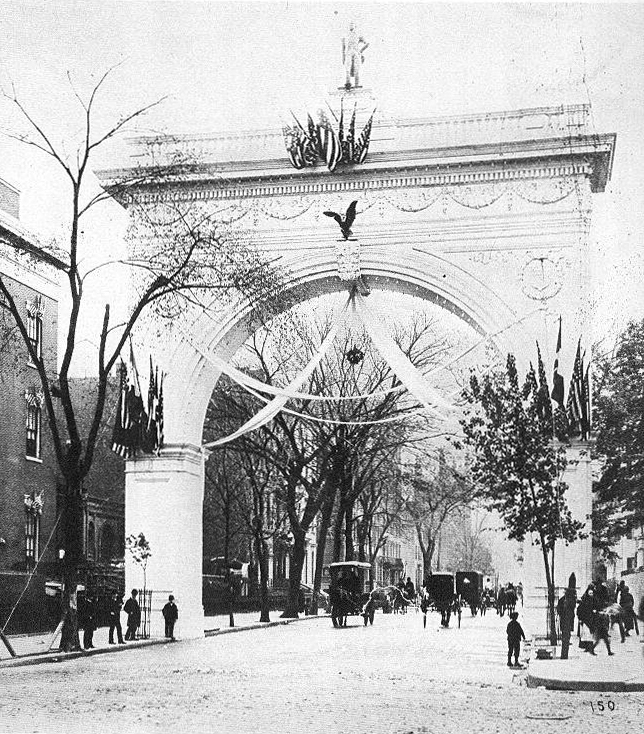

Washington Arch, 1895-1918. Washington Square Park, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

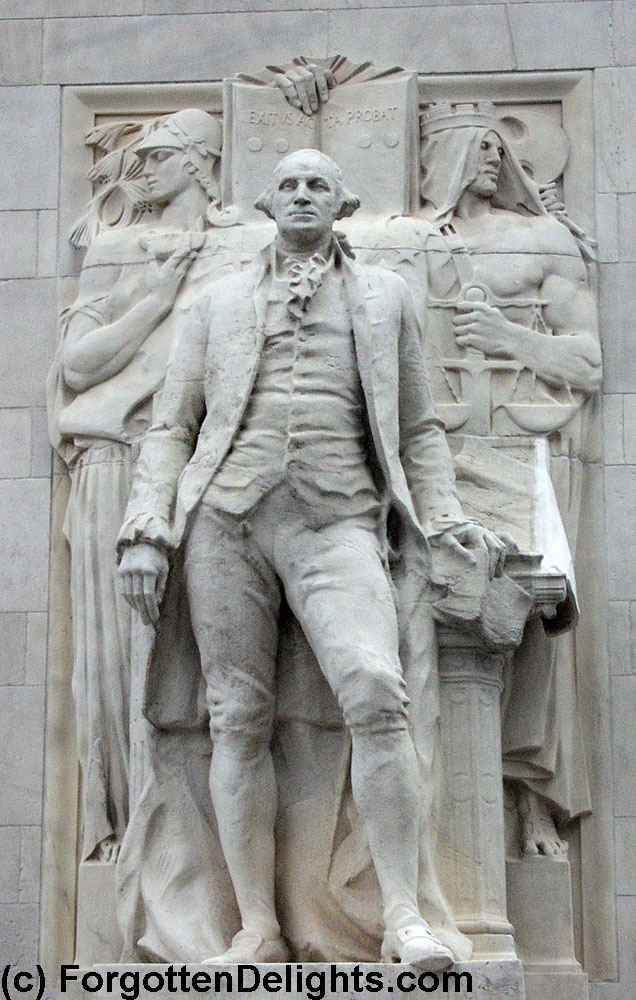

Washington as Commander in Chief

Washington as President

This essay is from Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan (OMOM).

About the sculpture

The symbolism of the Washington Arch, a marble version of one of four wooden triumphal arches erected in 1889 to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of George Washington’s first inauguration, is nearly as complex as that of French’s Continents. As in the Continents, the elements add up to a theme more complex than any single figure could convey.

On the northeast side of the Arch stands Washington as commander-in-chief. The caped cloak, tricorn and gloves recall the brutal winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge. Yet Washington looks into the distance, upright and unmoving: feet parallel, weight evenly balanced, hands resting on the hilt of an unsheathed sword. He’s prepared to fight, yet calm and commanding—two of the qualities his compatriots most admired in him, and that helped his soldiers endure grueling periods such as those at Valley Forge. (See here for a sculpture representing Washington at Valley Forge.)

At Washington’s feet are the business end of a cannon, and a cannonball. Flanking him are two allegorical figures in low relief. The figure on our left, Fame, carries the palm branch that signifies peace or fame. She also holds a trumpet, the usual allegorical way of announcing fame (hence “blowing your own horn”). Valor, on our right, wears a helmet and carries a sword in his left hand, the hilt raised to his shoulder. Behind his head are oak leaves, symbolizing courage. Between the two allegorical figures is a blank shield encircled by a wreath, which frames and thus emphasizes Washington’s head.

On the right side of the Arch, Washington as president wears an elegant coat, waistcoat and knee breeches. He stands relaxed, weight on one leg, holding an open book and resting his hand on a lectern. It’s the pose of a public figure rather than a scholar.

To the left of this Washington stands Wisdom, represented as the helmeted Greek goddess Athena. In her right hand she raises a lamp (?). Her right arm presses a long scroll against her body. Behind Wisdom’s head are clumps of pine needles, perhaps a reference to Washington’s Southern heritage.

On Washington’s other side stands the muscular figure of Justice, wearing a battlemented crown and holding the traditional scales and sword. Instead of wearing a blindfold, he has simply closed his eyes. Behind Justiceis a curved ax head whose handle Wisdom’sleft hand grasps. Perhaps it refers to the execution of a sentence once Justice has decided the matter.

Behind Washington’s head, carved on the pages of an open book that Justice grips with his right hand, is Washington’s motto: Exitus acta probat, “The result (or outcome) justifies (or tests, or proves) the deed.” In its colloquial translation, “The end justifies the means,” it’s an unexpected motto for a man as principled as Washington. A better translation – buttressed here by its close relationship to Justice – might be, “Judge me by the results of my actions.”

The two major sculptural groups on the Arch show two facets of Washington: as a renowned and courageous military leader, and as a wise and just civilian leader. The subsidiary decoration reinforces and elaborates those images. Above the keystones on the north and south side are fierce American eagles by Philip Martiny. Flanking them in the spandrels are winged figures by MacMonnies, sculptor of Nathan Hale. Fame blows a trumpet; War brandishes a trident and a laurel wreath.

In the upper level of the Arch are four coats of arms.

At the northeast side, above Washington as commander-in-chief, are the arms Washington adopted from his British ancestors, bearing three stars above two bars. (These may have been Betsy Ross’s inspiration for the Stars and Stripes.) Below the shield on a banner is the same Latin motto that appears behind the figure of Washington as president. At the northwest, above Washington as president, is the Great Seal of the United States. On the southwest are the arms of New York City, and on the southeast, those of New York State.

The inscription at the top of the south side of the Arch reads, “Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair. The event is in the hand of God. – Washington.” The quote in full is:

It is too probable that no plan we propose will be adopted. Perhaps another dreadful conflict is to be sustained. If, to please the people, we offer what we ourselves disapprove, how can we afterwards defend our work? Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair. The event is in the hand of God. — Washington, 1787 (reported by Gouverneur Morris, 1799)

This quote summarizes the type of man Washington was, and the type of men he hoped to associate with and lead.

The message of the complex imagery on the Arch is more than the sum of its parts. It’s a tribute to the Father of Our Country as a courageous military leader, a wise and just civilian leader, and a man of incorruptible integrity.

Evolution of the Arch

“Temporary” architecture was common for major celebrations in the late 19th century: most of the buildings for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago (see Columbus in Central Park) were built to endure only for the length of the fair (1892-1893). New York had its share of such structures, including 4 arches erected in 1889 to honor the centennial of Washington’s inauguration.

About the subject

The statues on the north side of the Washington Arch show Washington as commander-in-chief and as president, but the Arch’s only inscription refers to Washington’s other important contribution to the newly independent United States: his participation in the Constitutional Convention.

A mere five years after he had accepted General Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, Washington saw the United States disintegrating under the toothless Articles of Confederation. When mobs stormed Massachusetts courthouses during Shays’s Rebellion (1786-87), Washington wrote to Henry Lee:

I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds, that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon any country. . . . It is hardly to be supposed, that the great body of the people, though they will not act, can be so shortsighted or enveloped in darkness, as not to see rays of a distant sun through all this mist of intoxication and folly. . . . Let us have [a government] by which our lives, liberties, and properties will be secured, or let us know the worst at once. . . . If defective, let it [the Articles] be amended, but not suffered to be trampled upon whilst it has an existence.

Washington had hoped to retire to Mount Vernon, but in 1787 acquiesced when Virginia chose him as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. In the same room where the Declaration of Independenceand the Articles had been signed, and where the Congress met that had been his titular superior during the Revolutionary War, Washington was unanimously elected president of the Convention.

He arrived punctually for every session, six days a week for over four months, but hardly ever spoke. Perhaps he feared his authority would have disproportionate influence on the debates. The statement attributed to him by Gouverneur Morris (see above) was probably made outside the official sessions Yet Washington’s mere presence among these men who had voted him commander-in-chief, served with him in the army, or visited him at Mount Vernon, was enough to remind the delegates of the exacting thought and unbreached integrity that would be required to hammer out a practicable governing document for the United States.

More on Washington

Washington was named commander-in-chief of the Continental Army on 6/15/1775. His acceptance (from the notes of the Continental Congress, 6/16/1775):

Mr. President, Tho’ I am truly sensible of the high Honour done me, in this Appointment, yet I feel great distress, from a consciousness that my abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important Trust: However, as the Congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous duty, and exert every power I possess in their service, and for support of the glorious cause. I beg they will accept my most cordial thanks for this distinguished testimony of their approbation.

But, lest some unlucky event should happen, unfavourable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered, by every Gentleman in the room, that I, this day, declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the Command I am honored with.

As to pay, Sir, I beg leave to assure the Congress, that, as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to have accepted this arduous employment, at the expence of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any proffit from it. I will keep an exact Account of my expences. Those, I doubt not, they will discharge, and that is all I desire.

Here’s the address he gave to his troops before the Battle of Long Island, 8/27/1776.

The time is now at hand which must probably determine whether Americans are to be freemen or slaves, whether they are to have any property they can call their own, whether their house and farms are to be pillaged and destroyed, and themselves consigned to a state of wretchedness from which no human efforts will deliver them. The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die.

The Republic of Greenwich Village

On January 23, 1917, John Sloan, Marcel Duchamp, and several other young artists of Greenwich Village (a mecca for artists and assorted bohemian types) sneaked into the side door of the Washington Arch and climbed to the top. There, having imbibed a fair amount of wine, they shot off pop guns and read a “Declaration of Independence” for Greenwich Village. The Declaration consisted of the word “whereas” repeated over and over and over and over – probably an inspiration of Duchamp, the Dadaist who named a urinal Fountain and entered it in exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917. For more on the Washington Arch escapade, see Ross Wetzsteon, Republic of Dreams. Greenwich Village: The American Bohemia, 1910-1960.

Hermon MacNeil

MacNeil (1866-1947, b. College Point, Queens) studied in Rome and Paris, then worked under Philip Martiny for the Columbian Exposition of 1893. His favorite subject was Native Americans (the Metropolitan Museum has a copy of his Sun Vow), but among his best known works are the 1907 McKinley Memorial in Columbus, Ohio and the pediment of the Supreme Court in Washington. MacNeil also designed the “Standing Liberty” quarter, minted from 1916 to 1930.

Manhattan has this figure of Washington as commander in chief on the Washington Arch. Queens has the Flushing War Memorial, 1920, and the Bronx has four busts in the Hall of Frame of Great Americans (BronxCommunity College).

Alexander Stirling Calder

Calder (1870-1945, b. Philadelphia), son of Scottish sculptor Alexander Milne Calder, studied with Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, then in Paris. He designed huge groups for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition before turning to garden and fountain sculptures.

Manhattan has Washington as President on the Washington Arch and four actresses on the Miller Building, ca. 1927-1929 (1552 Broadway). He was the father of that very mobile sculptor Alexander Calder, whose Guichet, 1963, stands at Lincoln Center.

Frederick MacMonnies

MacMonnies, creator of the brilliant Nathan Hale, did designs for the piers where the two Washingtons now stand, but only completed the allegorical figures for the four spandrels that flank the keystones of the arch.

More

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.