This essay is adapted from Chapter 6 of Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. I’ve kept cross-references to other chapters in the book, all of which will eventually be updated and posted on this site. Click on “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan book” in the Obsessions cloud at lower right to see which are already here.

- Alexander Lyman Holley

- Sculptor: John Quincy Adams Ward. Pedestal: Thomas Hastings.

- Dedicated: 1890.

- Medium and size: Bronze bust (approximately 3.25 feet), limestone pedestal (approximately 10.25 feet).

- Location: Washington Square, west of the central fountain. Subway: A, B, C, D, E, F, V to West 4th.

About the sculpture

With his direct gaze and upright carriage, Holley appears to be intelligent, levelheaded and self-controlled – desirable characteristics in a man who routinely built and operated steel-making plants. His curly hair and the nubbly texture of his overcoat nicely set off his handsome, strong-featured, unlined face, with its broad forehead and cavalry mustache. At the right, a twig of oak leaves alludes to the honor being paid to him.

Doubtless Holley slept, laughed at jokes, and tied his shoes, but this bust presents a stripped-down Holley: the features and expression that show him as the type of person who understood dangerous industrial procedures and complex machinery, and who confidently relied on his own judgment to control them. Those characteristics, and of course his detailed knowledge of the Bessemer process (see About the Subject below), made him invaluable to the American steel industry in the late nineteenth century.

Twenty years after Holley introduced the Bessemer process to the United States, when Americans were as blasé about rolled steel as today’s ten-year-olds are about the Internet, the New York Times derided the idea of setting Holley’s bust up in a public place: “The time is coming . . . when sites for statues in the Park will be too scarce to be assigned to effigies from which the general public will derive its first knowledge that the originals of them have existed” (4/24/1890). But like those who donated funds for Dodge and Sims (Chapters 24 and 47), Holley’s colleagues thought he deserved to be honored:

Our heroes are not alone those who have repelled invasion, suppressed rebellion, or broadened our boundaries by conquests of the sword or pen, but in a better sense those who have made the great forces of nature subservient to our purposes, and placed at the command of industry and enterprise the means which have rendered possible a national development that commands the admiration of the world. (James C. Bayles at the dedication of the Holley bust, New York Times 10/3/1890)

Art’s most important purpose is to help you reaffirm your own view of the world. (See Hale, Chapter 8.) The right art can remind you of the sort of person you want to be: a brilliant inventor like John Ericsson, a courageous patriot like Nathan Hale, a dignified leader like Washington (Chapters 2, 8, 6). For Holley’s colleagues and for anyone familiar with Holley’s life’s work, this sculpture is a reminder of how much one individual can accomplish through diligent thought and hard work.

About the subject

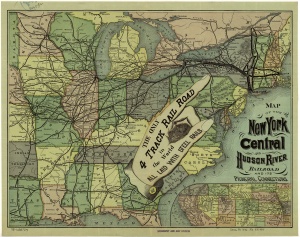

After the B&O Railroad’s success in 1830 (see Cooper, Chapter 10), railroad tracks snaked across the United States. A thousand miles were laid by 1835, thirty thousand by 1860. But under the enormous weight of locomotives and freight, iron rails often lasted barely two years. When the next great age of railroad expansion occurred, immediately after the Civil War, the life of rails was closer to fifteen years, because they were made largely of Bessemer steel – a material whose use in America was brought about almost single-handedly by Alexander Lyman Holley (1832-1882).

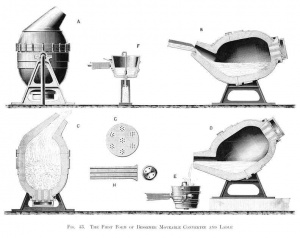

During a Civil War trip to Europe to study weaponry, Holley observed Henry Bessemer’s new process for making steel. Steel was more resilient than iron and could be poured or rolled directly into any desired shape. The major advantage of Bessemer’s process, however, was its speed.

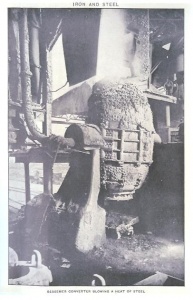

Before Bessemer’s time, producing even small quantities of steel required weeks of intensive labor. Bessemer perfected a method of blowing a tremendous blast of air through melted pig iron to remove all impurities, and then adding the desired amount of carbon while the metal was still molten. A Bessemer converter could produce two tons or more of steel in about twenty minutes. Because it was homogeneous and its carbon content precisely controlled, it was higher-grade steel than any produced previously.

Here’s Holley’s description of what the steel-making process looked like:

A million balls of melted iron tearing away from the liquid mass, surging from side to side and plunging down again, only to be blown out more hot and angry than before. Column upon column of air, squeezed solid like rods of glass by the power of 500 horses, piercing and shattering the iron at every point, chasing it up and down, robbing it of its treasures, only to be itself decomposed and hurled out into the night in a roaring blaze. As the combustion progresses the surging mass grows hotter, throwing its flashes of liquid slag. And the discharge from its mouth changes from sparks and streaks of red and yellow gas to thick full white dazzling flame. … The converter is then turned upon its side, the blast shut off, and the carburizer run in. Then for a moment the war of the elements rages again – the mass boils and flames with higher intensity and with a rapidity of chemical reaction, sometimes throwing it violently out of the converter’s mouth. Then all is quiet, and the product is steel, liquid, milky steel that pours out into the ladle from under its roof of slag, smooth, shiny, and almost transparent. – Holley, ca. 1870-1880 (quoted in Morison, Men, Machines and Modern Times)

Grasping that Bessemer’s process could have a tremendous impact on American industry, Holley persuaded his employer to purchase the American rights to the process and to license its use to other American manufacturers. His designs were the basis for eleven of the twelve Bessemer plants eventually built in the United States. In just thirteen years, annual production of Bessemer steel rose from 3,000 tons to well over a million. Most of it was used by the railroads, whose mileage nearly doubled in the six years after 1867, from 39,276 to over 70,000 miles.

The last American Bessemer plant was phased out in the 1970s. A hundred years earlier, however, Holley had already recognized the advantages of the Siemens brothers’ open-hearth process of steel making. He convinced several clients of its value, but died in 1882, at age 50, before he could supervise construction of such plants.

Holley is a perfect example of the businessman acting as the link between the scientist’s theoretical discoveries and the material goods such discoveries make possible. Although neither a technological nor a financial genius, Holley made a respectable living by spreading a new technology. In so doing, he brought radical and beneficial innovations not only to steel-makers but to all American industry. The life of everyone who rode a train or used goods transported by rail – and that meant nearly all Americans – was immeasurably improved by Holley’s dedication to doing his best in his chosen field.

The New York Times marvels at steel-making

In 1868, even the New York Times marveled at the mass production of steel:

It is neither magic nor alchemy, but straightforward, inductive reasoning and downright, patient, organized, costly work that lays open the great unknown, and utilizes its treasures.

The modern revolution in metallurgy is, perhaps, less striking, but more wonderful than all the others. The wonder of ocean telegraphy is new every morning, while the furnace smokes silently and unobserved. But the smoke of the furnace will tell you tales of nature’s secrets unlocked, of startling transformation, of fathomless search, of baffling experiment, of patient endeavor, of endless obstacles, of intellects gone made, or money burned up, of a forlorn hope fighting against the Powers of the Air, but fighting to win.

Of all the agencies in the material progress of the times, iron, in its various forms and combinations, holds the first place. Its loss would be a calamity only surpassed by the loss of bread; while its cheaper, wide and better production would electrify every human enterprise. …

We have thus briefly referred to the grandeur and the difficulty of the great material problem of the age, not to account for failure, but to celebrate success.

–“The Bessemer Process. The Production of Cheap Steel in America. Completion of the Parent Works at Troy,” New York Times 8/9/1868

Inscription

The tripartite pedestal for Holley was designed by architect Thomas Hastings of Carrere and Hastings, the firm that later designed the New York Public Library, the Frick mansion and the western approach to the Manhattan Bridge. The white marble has not held up well to New York City’s pollution. After repeated cleanings, the inscription is almost illegible. This transcription is from the NYC Park Department’s site.

HOLLEY

BORN IN LAKEVILLE

CONN., JULY 20TH 1832

DIED IN BROOKLYN, N.Y.

JANUARY 29TH, 1882

IN HONOR OF

ALEXANDER LYMAN HOLLEY

FOREMOST AMONG THOSE

WHOSE GENIUS AND ENERGY

ESTABLISHED IN AMERICA

AND IMPROVED /THROUGHOUT THE WORLD

THE MANUFACTURE OF

BESSEMER STEEL

THIS MEMORIAL IS ERECTED

BY ENGINEERS

OF TWO HEMISPHERES

More

- John Quincy Adams Ward (b. Urbana, Ohio, 1830, d. New York City, 1910) worked with Henry Kirke Brown on the Washington at Union Square, dedicated in 1856 (Outdoor Monuments Chapter 13). Far earlier than his contemporaries, Ward believed American sculptors should present American ideas and be trained in America: he never studied abroad. For fifty-odd years, he was known as the “Dean of American Sculpture.” Indian Hunter, 1869 (Central Park, near the Mall), established his reputation. Manhattan has Washington, Greeley, Holley, Conkling, Dodge and Shakespeare (Outdoor Monuments Chapters 6, 7, 11, 18, 24, 37), as well as the Seventh Regiment Memorial,1869 (Central Park, West Drive at 67th Street), and the Pilgrim, 1885 (Central Park, east end of the 72nd-Street Traverse). The original sculptures of the New York Stock Exchange pediment were Ward’s, but they’ve been replaced with copies. Brooklyn has Henry Ward Beecher, 1891 (Columbus Park).

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and recurring support: details here.