This week’s post includes a number of seventeenth- and eighteeenth-century American artworks at the Wadsworth. The introduction to this series, about the Wadsworth family and the Wadsworth Atheneum, is here. For all posts in the series, click here; for posts on American art at the Wadsworth in roughly chronological order, see the end of this post.

The bust of Samuel Colt in last week’s post reminded me that I often find the Neoclassical style intolerably calm and sedate. Why did such a rambunctious people as Americans adopted it? The answer is that when Americans became wealthy enough to pay well-trained artists, those artists were trained in Europe. They very frequently continued to work in the style in which they were trained. In Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, that meant Neoclassicism. For more on the the story behind Neoclassicism, see Seismic Shifts in Subject and Style: Nineteenth-century French Painting and Philosophy.

In this post: a short survey of American art of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, by some artists who had training and some who did not. Spoiler: there is not a continuous progression to from less well-executed to more technically proficient art. Not all artists spent years training, and not all purchasers could afford top-of-the-line artists. Just as today there’s a market for genuine Gucci and for Gucci knock-offs, so in the early days of the United States (and even today!), there is a market for extremely high-quality artworks as well as more affordable but less accomplished ones.

1664: Elizabeth Eggington

This portrait of a young girl is one of the earliest American paintings that can be dated; it was probably painted in Boston or Dorchester. The artist doesn’t seem to have had much knowledge of anatomy: Elizabeth’s proper left arm (i.e., her left arm, not the one on our left) looks like a cylinder, without indication of bones and muscles. Her proper right arm and hand are virtually flat. And that neck reminds me of the Tenniel illustration for Alice in Wonderland after she’s eaten the cake. Meanwhile in Europe in the same decade (1660s), Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals were all at work.

Ca. 1715-1735: Arm Chair

This rather ornate chair was inexpensive for the time, because its uprights and supports were turned on a lathe. Only the rail at the top, the arms, and the claw feet are hand-carved.

This blog post includes two pieces of furniture, to illustrate the point that American craftsmen could be quite skilled. Why are they so much more accomplished than painters or sculptors? If you’re a competent woodworker, you can observe a master’s work and imitate it. But if you’re a painter or sculptor, you need a unique point of view, and you need some technical skill. Otherwise egregious errors in anatomy, perspective, etc., will creep in to distract your viewers.

To acquire the basic skills that innovators in painting and sculpture devised over several millennia, an artist either needs training by another professional, or a multitude of examples to study. In the early United States, few large private collections existed, and even fewer museums open to the public. American painters and sculptors had no way to learn their craft well until they began to study in Europe in the late eighteen century.

Ca. 1741-1747: Gershom Flagg IV; Mrs. Gershom Flagg IV (Hannah Pitson)

Robert Feke (ca. 1707-ca. 1752) was an itinerant artist, traveling throughout New England to paint portraits of those wealthy enough to afford such luxuries. Gershom Flagg was an architect, builder, and landowner based in Boston. These portraits of Flagg and his wife are infinitely more accomplished than the 1664 portrait of Elizabeth Eggington at the beginning of this post. Unless you looked at Feke’s other portraits of women, you wouldn’t realize how formulaic they are: same pose, similar facial shapes and hair styles, similar dresses.

Possibly Feke simply lacked imagination, but I’m guessing that he resorted to a formula in order to paint more quickly, so that he could make enough to earn his living by his art.

Ca. 1778: Portrait of a Lady (Mrs. Seymour Fort?)

Now that’s a portrait of a unique individual, from the shape and texture of her face and hair down to the task she’s performing with her hands. And they’re distinctive hands: they belong to an elderly woman, but they’re still capable of working intricate lace. They add to our knowledge of her character, as do the hair, the bonnet, the dress, the chair, the posture.

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) grew up in Boston, whose wealthy citizens did own some art, and he spent several of his formative years with a stepfather who was a painter and engraver. By age 14, Copley was painting portraits. In the 1760s and early 1770s he created such notable works as Paul Revere and Boy with Flying Squirrel. In 1774, as the situation in the American colonies became increasingly tense, Copley moved to London, where he studied British portraiture. His later portraits include this one of Mrs. Fort (?) and one of his step-niece Abigail Bromfield Rogers.

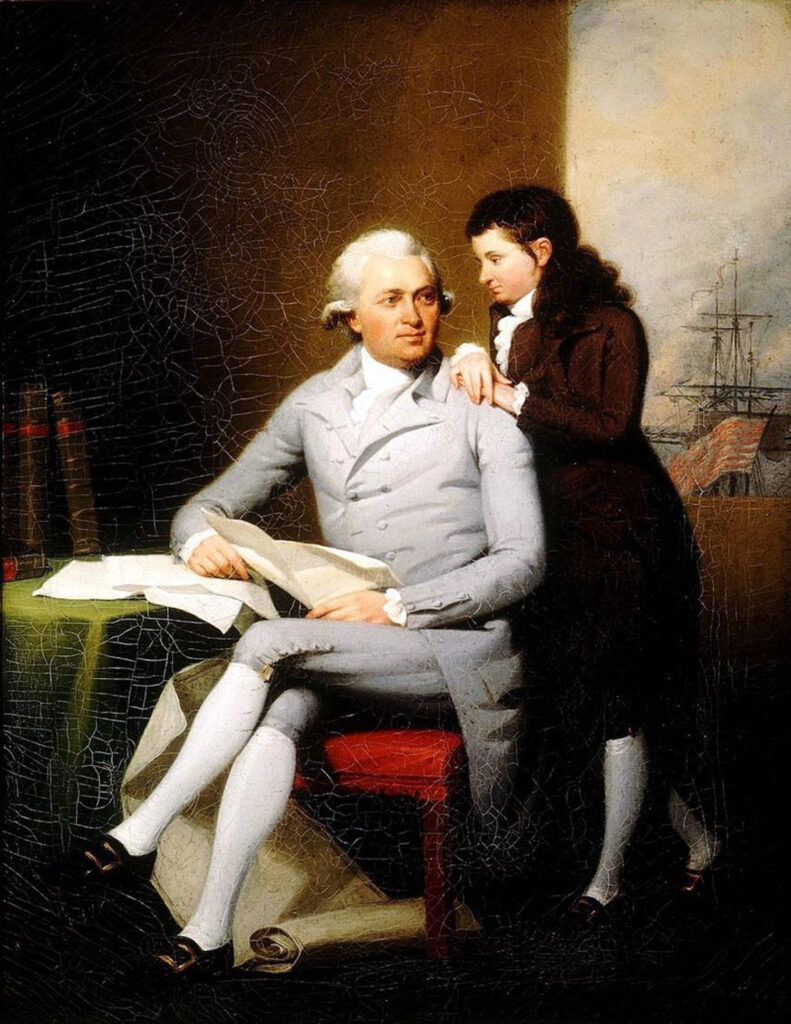

1784: Jeremiah Wadsworth and His Son Daniel

John Trumbull, a Connecticut native, trained in London with Benjamin West, an American who studied in Europe and then settled down in England, where he became a famous painter of portraits and historical scenes. Trumbull eventually became famous for his representations of Revolutionary War scenes and figures, including the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, 1819-1820.

Like Copley, Trumbull makes every detail of the portrait contribute to our knowledge of the sitters, especially the way Daniel leans on his father to suggest the close tie between the two of them. Daniel later married Trumbull’s niece, and in 1842 founded the Wadsworth Atheneum: more here.

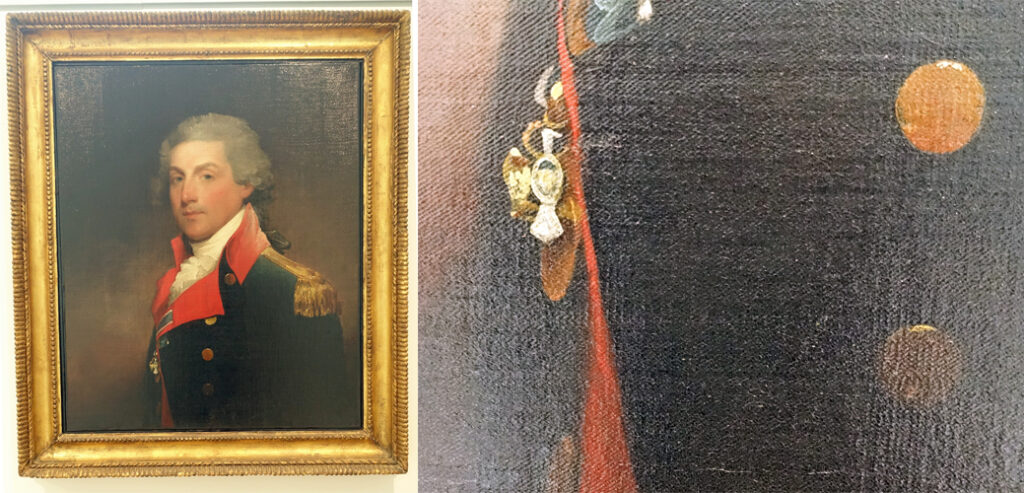

Ca. 1794: General Aquila Giles

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), a native of Rhode Island, studied with a New England portrait painter. Then, like Copley, he fled to England during the Revolutionary War. There he, too, studied with Benjamin West. Stuart is best known for painting produced scores of portraits of George Washington, including the one used on the one-dollar bill.

In this portrait of a Revolutionary War general, the waist-length pose in three-quarter view is very similar to the one used for Elizabeth Eggington … but what a difference in the way Stuart renders anatomy, light and shade, color, and background, and especially in the way he suggests the personality of the sitter!

1794: Benjamin S. Judah

During the early years of the Revolutionary War, Ralph Earl (1751-1801) painted four pictures that were engraved by Amos Doolittle and used for pro-American propaganda. Earl also painted patriots such as Roger Sherman, who signed the Declaration of Independence. But in 1778 Earl declared that he was a loyalist and (like Copley and Stuart) he fled to England. There he, too, studied with Benjamin West, and became an accomplished portraitist in the latest aristocratic British style.

Returning to America after the War ended, Earl found there wasn’t much of a market for aristocratic portraits. In 1786, he was imprisoned in New York for failing to repay a small loan. Alexander Hamilton and the other members of the Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors encouraged Earl to earn money to pay off his debt by painting portraits of the Society’s friends and family. Among them was Earl’s most famous work, a portrait of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton.

After Earl was released from jail in 1788, he adapted his style to suit the republican tastes of his New England sitters, painting them for another two decades. Like Robert Feke, Earl developed a formula for his portraits, which are often strongly reminiscent of each other. This portrait of Benjamin Judah at the Wadsworth is close kin to a 1789 portrait by Earl in the Metropolitan Museum. For the 1792 double portrait of the Ellsworths in the Wadsworth, see here.

Ca. 1804: Sideboard

By the late eighteenth century, sideboards were a popular feature of American dining rooms: they allowed one to display high-end silver, glass, and ceramics. Aaron Chapin (1753-1838), whose shop was in Hartford, created this elegant piece from mahogany, satinwood, holly, ebony, and brass. It simple lines make it Neoclassical style, as opposed (for example) to the very elaborate decoration of Louis XV furniture.

1850: Seated Figure with Lamb and Cup

If you didn’t know the date, you might guess that this painted wooden sculpture was created in the same period as the portrait of Elizabeth Eggington (1664). But it’s a memorial to Sarah Reliance Ayer and Ann Augusta Ayer, ages 3 and 1, who died in 1849. Asa Ames (1824-1851), a self-trained artist, worked in northern New York State. In Europe during this period, Barye (creating complex animal sculptures), David d’Angers, and Thorvaldsen (both Neoclassicists) were at work.

1901: A Cup of Tea

Bringing matters full circle: by the beginning of the twentieth century, the colonial era (including cooking over open hearths) was so long ago that it had a nostalgic appeal. Enoch Wood Perry (1831-1915) specialized in representations of colonial times. No American painter of the colonial period would have been able to depict an interior with such accurate perspective, or do the subtle light and shadow in this work.

More

- When I visited the Wadsworth, visitors were sent through the galleries in reverse chronological order due to social distancing. If you’d rather read the posts in order (seventeenth through twentieth centuries), the sequence would be as follows. Part 1 is the introduction to the series.

- part 12: 16th to early 19th centuries, including Copley, Trumbull, and Earl

- part 2: late 18th c., including Copley and Earl

- part 3: early and mid-19th c., early Hudson River School, including Cole and Church

- part 11: mid-19th c., including the Colt legacy and the Charter Oak

- part 4: mid-19th c., including Church and Bierstadt

- part 6: late 19th c. painting and sculpture, including Church, Remington, and Bierstadt

- part 5: late 19th c. painting, including Church and Heade

- part 9: late 19th and early 20th c. painting and sculpture

- part 10: late 19th and early 20th c. sculpture, including MacMonnies and Frishmuth

- part 8: early and mid-20th c. painting and sculpture, including Andrew Wyeth

- Part 7: survey of images of Niagara Falls, from the 17th to 21st centuries, including Trumbull, Cole, Bierstadt, and Church.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon print and Kindle formats.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.