In 2020, I emailed 157 art-related items to my members of my free Sunday Recommendations list. (To join, just ask me: DuranteDianne@gmail.com.) For supporters, I recommended 51 more items. The items in this and the following post are my own favorites. Among them are 17 items that were originally shared only with supporters, which are marked with an asterisk.

Literature: Novels

* Renault, Mary. The Praise Singer (1978). Renault, one of the great writers of historical fiction, set many of her works in Ancient Greece. The main character in this one is Simonides of Keos (ca. 556-469 BC), a lyric poet in the period when mainland Greece and the Greek colonies in Ionia (Turkey) were under the rule of tyrants. One of my favorite passages: “Tell a man what he may not sing, and he is still half free; even all free, if he never wanted to sing it. But tell him what he must sing, take up his time with it so that his true voice cannot sound even in secret – there, I have seen, is slavery.”

Runners-up:

- White, Randy Wayne. Doc Ford / Sanibel Island mysteries (1990-present). I’m on the fifteenth of White’s 26 Doc Ford novels. Doc Ford is an interesting, complex man notable for his honesty, courage, and integrity. Occasionally he speaks a thought-provoking line such as: “In any conflict, the boundaries of behavior are defined by the party that cares least about morality.” I came across White’s books at Doc Ford’s Rum Bar & Grill in Sanibel Island, where the author lives. Should be read in order.

- Dunnett, Dorothy. Dolly and the Doctor Bird (1971). My favorite mystery by this author, whose books assume a high level of attention and intelligence, as opposed to many modern novels that require a high level of … toleration. Dunnett also wrote several multi-volume historical series. I blame her Lymond Chronicles for the fact that my German is nicht so gut: those six books seriously distracted me the summer I was taking an intensive course in German. The link above is to Amazon (I get a minor commission on items sold through such links), but there are much cheaper copies of this and many other books available on ViaLibri.net, an aggregator site for old and rare books.

Literature: Drama

* Rattigan, Terence. While the Sun Shines (1943). Rattigan’s longest-running West End play. This nicely done BBC Saturday Night Theatre reading is from 2020, assuming the YouTube date is accurate. This review calls the play “effervescently escapist”. You’ll know if you need some of that just now.

Literature: Short stories

* Webster, Henry Kitchell. “The Second Rescue” (1916). A romance (sort of) set on the Great Lakes; the video is here (70 mins.). This story will appear in the third volume of Webster’s short stories, which I’ll be publishing in 2021.

Literature: Poetry

This was a difficult category to narrow down! Tied for winner:

- Etherege, Sir George (1635-1691). “To a Lady asking him how long he would love her.”

It is not, Celia, in our power

To say how long our love will last;

It may be we within this hour

May lose these joys we now do taste.

The Blessed, that immortal be,

From change in love are only free.

Then since we mortal lovers are,

Ask not how long our love will last;

But while it does, let us take care

Each minute be with pleasure past.

Were it not madness to deny

To live because we’re sure to die?

- * Teasdale, Sara (1884-1933). “Tonight.”

The moon is a curving flower of gold,

The sky is still and blue;

The moon was made for the sky to hold,

And I for you;

The moon is a flower without a stem,

The sky is luminous;

Eternity was made for them,

Tonight for us.

Runners-up:

- Cordair, Quent. “Toast” (2019). From the collection My Kingdom.

- Lawson, Henry (1867-1922). “The Men Who Sleep with Danger.” By association with White’s Doc Ford mysteries.

- * Teasdale, Sara (1884-1933). “Wood Song” (1917).

- * Hugo, Victor. “Jeanne était au pain sec” (“Jeanne was sentenced to dry bread”, 1877). In 1871, Hugo became the guardian of his grandchildren Jeanne and Georges. One of his last published works was L’Art d’être grand-père (The Art of Being a Grandfather): see this article on a recent translation of L’Art, with excerpts from more of the poems. In the late nineteenth century, children were still expected to be seen and not heard. Judging from these poems, many people were shocked by the way Hugo, a towering figure in the literary and political spheres, indulged his grandchildren. In the rough translation that follows, I’ve tried to keep the terminology of the criminal courts. (Shades of Jean Valjean!) Although it’s slightly stiff in English, I’ve also kept Hugo’s use of the French “on” (“one”) rather than “he” or “she”, because it makes the authority figure (a governess? housekeeper? butler?) more forbidding. The poem is in rhyming couplets, but alas, the syntax of English is so different from French that a literal translation loses the much of the fun: e.g., Hugo’s rhyming forfeiture (penalty) with confiture (jam).

Jeanne was sentenced to dry bread in a dark room

For some crime or other; and, failing in my duty,

I went to see the condemned one while she was still suffering the penalty.

And against the rules, I slipped her, in the dark,

A pot of jam. All those in whom, in my city-state,

The good of society reposes,

Became indignant, and Jeanne said, in a gentle voice:

“I won’t touch my nose with my thumb;

I won’t let myself be scratched any more by the kitten.”

But one said indignantly: “This child knows you;

She knows just where you’re weak and lax.

She sees you always laughing when one gets upset.

No exercise of authority is possible. Every moment

The system is troubled by you; power is relaxed;

No moral order. The child has nothing to arrest her.

You demolish it all.” – And I lowered my head,

And I said: “I have no answer for that;

I was wrong. Yes, it’s with such indulgences as these

That one leads the people to their doom.

Let me be sentenced to dry bread.” “You deserve it, certainly,

And one will impose the penalty.” – Then Jeanne, in her dark corner,

Said to me very quietly, raising her beautiful eyes,

Full of the authority of gentle creatures:

“All right then: me, I’ll bring you some jam.”

Painting

* Friedrich, Caspar David. Woman at a Window (1822). A lovely work by a German Romantic. Google sees a lifeless room and a woman longing for the unknown, but I see calm curiosity and the coming of spring. The original is at the Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

- * Runner-up: Campion, Pascal. Room to Grow, A Collection of Images and Stories (2019). Campion, a graphic artist, usually works via Photoshop. I like the sense of life of many, many of the hundreds of drawings that are illustrated in this glossy 9×12″, 200-page book. This artist has a wide variety of moods, but he keeps coming back to things that matter to me: balancing work and life, love of family, relationships, sources of inspiration. The book includes occasional page-long answers to the questions and comments Campion hears most often. A lot of current material is available on Campion’s Instagram feed (@PascalCampionArt) and his website.

Sculpture

Another difficult category to narrow down.

Winner (it’s been among my favorite sculptures for decades): [Greek]. Zeus of Artemisium (or Poseidon) of Artemisium (ca. 460-450 BC). Zeus shows a fabulous view of man, because to the Greeks, gods were just larger-than-life men. It was found in a wreck off Cape Artemisium, north of Athens, so its modern name has the happy effect of recalling the emergence of the glorious Greek Classical period. At the end of the sixth century BC, mainland Greece was a collection of small city-states. Then the ruler of the Persian Empire, having expanded from modern Iran into modern Turkey, arrived with a huge army and navy, intending to swallow up Greece. In 480 BC the Persians defeated the Athenians, Spartans, and allied Greeks on land at Thermopylae and on the sea at Artemisium. Then the Persians rampaged south through Attica, where (among much else) they destroyed the sculptures on the Athenian Acropolis. The Persians were finally defeated by the allied Greeks in September 480 BC, at the Battle of Salamis. Throughout the fifth century BC, the Greeks frequently referred to the defeat of the Persians in their literature, art, history, and public speeches. And they didn’t think of it as merely a military victory. The Greeks viewed it as the triumph of order over irrationality. The Persian ruler had absolute power, and most of his soldiers were slaves who had to be whipped into battle. In contrast, the Greeks were fighting for their freedom, for a local government in which they had some say, and for their way of thinking: independent, rational thought rather than the dictates of religion or a tyrant. After the Persians were driven out, Sparta resumed its former isolationism. Athens became the leader of a defensive alliance formed against future Persian attacks, as well as a cultural center for all Greeks. The confidence that the Greeks found after defeating the Persians shows in every detail of the multitude of artworks that were created over the following decades to replace works destroyed by the Persians. Among them were the Parthenon and its sculptures, and the Zeus of Artemisium.

Runners-up:

- Boquet, Simon-Louis. Archimedes (Louvre) (1788). A wonderful “portrait” of one of the ancient world’s greatest scientists, mathematicians, and engineers; see also the image in here. This work earned Boquet (1743-1833) his admission to the French Academy. Given the quality of the composition and technique, it can’t possibly have been his first work, and given that he lived another three decades, it was probably not his last; but I’ve been unable to find any other works by him via Google (English or French), the Louvre’s website, or the Frick Library’s database. Benezit (1924) mentions only this sculpture. Wikipedia (French) notes four bas-reliefs at the hôtel de Salm in Paris, which I haven’t found photos of. This is very perplexing. Could it be that all the knowledge and achievements of mankind are not yet on the Net?

- Settignano, Desiderio da. Portrait of a Little Boy (1455-1460). Donatello (ca. 1386-1466) often created works that were passionate, violent, or thought-provoking. See, for example, his Mary Magdalene, Herod’s Feast, and bronze David. But one of his most influential works was a simple relief. After centuries of medieval artists showed the Madonna and Christ Child as awe-inspiring figures, Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna showed them, touchingly and very humanly, as a mother and her child. The Pazzi Madonna sparked hundreds of paintings and sculptures in the “Sweet Style” in mid-fifteenth-century Florence. One of them is illustrated in my third post on the Gardner Museum in Boston. This exquisite portrait bust at the National Gallery in Washington is another lovely example. Desiderio’s contribution is the extremely subtle rendering of flesh, hair, and cloth; and that tremulous expression that looks about to change to … who knows what? For more on Donatello and the Pazzi Madonna, see Innovators in Sculpture, Chapter 8.

- Kitson, Henry Hudson. Minute Man, Lexington, Massachusetts (1900). This sculpture is later than the more famous one in Concord, by Daniel Chester French, and I prefer it. The blog post I used it in includes a quick review of the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

- Bartholdi, Frederic Auguste. Christopher Columbus, Providence, RI (1893). Imagine seeing this sculpture for the first time without knowing who it represents. What do you see? I see a person with an upright bearing, looking into the distance with a slight frown but pointing ahead, as if he’ll move onward despite his worries. To my mind, it’s about courage. It is, of course, Christopher Columbus, and I prefer this version (mentioned by Sam Axton on Facebook) to the many Columbuses in New York City, which I listed in this post back in 2016. The original version was designed by Bartholdi and cast in silver by the Gorham Manufacturing Company of Providence, as a celebration and a display piece for the 1892 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. (On Gorham, see this post; on the Columbian Exposition, this one.) The bronze version, a gift from the Elmwood Association to the city of Providence, was placed in Columbus Square in 1893. When I moved to Connecticut in August 2020, I anticipated being able to see it in person: Providence is barely an hour away. Alas, Columbus was defaced several times in the decade of the 2010s, and in June 2020, it was removed in the wake of the George Floyd protests – hauled off to an unknown storage site. A number of people who would not have had the courage to do what Columbus did stood around and clapped. Don’t read this article if you have a queasy stomach. But thanks to Wikipedia, I have two lovely photos to share with you, here and here. For my comments on politics and portrait sculptures, see here. Recommended for Columbus Day reading: “The Myth of the Stolen Country.“

- Salvi, Nicola, and others. Trevi Fountain, Rome (1732-1762); more photos here. Sometimes you just need exuberance combined with a high level of technical skill. Baroque art works (ca. 1600-1750) are good for that: think Vermeer, Velazquez, Rembrandt, Kalf, and of course Bernini and Caravaggio, whose works started the Baroque movement in sculpture and painting, respectively. By the mid-seventeenth century, painters and sculptors had available in their tool-kits almost every innovation that had been or would be devised, and their works are remarkable. That level of skill lasts through the nineteenth century, with considerable variation from 1600 to 1900 in what artists considered important enough to represent. For more on what happened in the late nineteenth century, see Seismic Shifts in Subject and Style, Innovators in Sculpture, and Innovators in Painting.

More

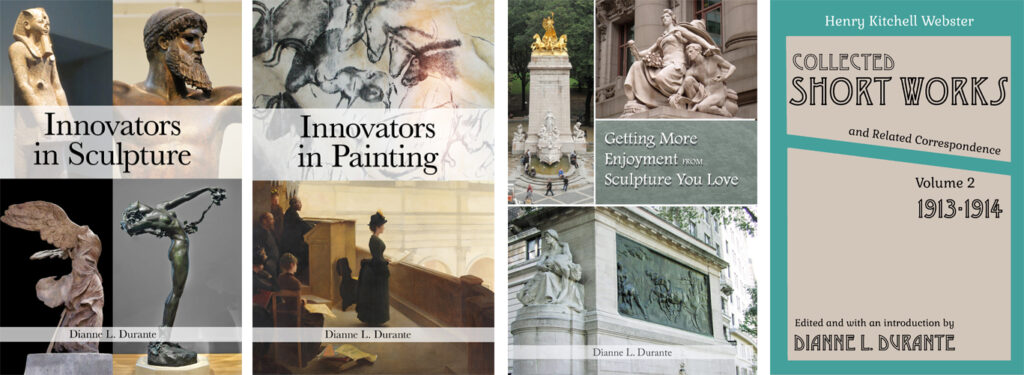

- In 2020 I published Innovators in Sculpture and Innovators in Painting, which have been in the works for many years. For why they’re unique, see here. I also published Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, an anthology of 16 essays demonstrating how to analyze sculpture. My edition of Henry Kitchell Webster’s Collected Short Works and Related Correspondence, volume 2 (1913-1914) appeared. All these are available in print and Kindle formats via my Amazon author page. And check out dozens of videos from 2020 on my YouTube channel. For more of my writings, see the list on the Books and Essays page.

- For favorites from earlier years, see the Favorite Recommendations and Photos link.

- Want wonderful art such as these recommendations delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.