This essay is adapted from Chapter 36 of Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. I’ve kept cross-references to other chapters in the book.

- Sculptor: Jeronimo Suñol. Pedestal: Napoleon Le Brun.

- Dedicated: 1894.

- Medium and size: Bronze (8 feet), granite pedestal (7.75 feet).

- Location: Central Park, south end of the Mall’s Literary Walk, just north of the 65th Street Traverse. Subway: 6 to 59th Street or F to Lexington Avenue—63rd Street.

Washington Irving on Columbus

Certain it is that at the beginning of the fifteenth century, when the most intelligent minds were seeking in every direction for the scattered lights of geographical knowledge, a profound ignorance prevailed among the learned as to the western regions of the Atlantic; its vast waters were regarded with awe and wonder, seeming to bound the world as with a chaos, into which conjecture could not penetrate, and enterprise feared to adventure. . . . It is the object of the following work, to relate the deeds and fortunes of the mariner who first had the judgment to divine, and the intrepidity to brave the mysteries of this perilous deep; and who, by his hardy genius, his inflexible constancy, and his heroic courage, brought the ends of the earth into communication with each other. The narrative of his troubled life is the link which connects the history of the old world with that of the new. — Washington Irving, Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 1828

About the sculpture

What a shocking change from the Columbus Monument (Chapter 35)! This Columbus has a wrinkled brow, bags under his eyes, deep lines at the corners of his mouth, a slight double chin, and a receding hairline. Hatless and humble, he gazes heavenward. He stands upright, facing forward rather than twisting like the Columbus at Columbus Circle—a static figure. This appears to be Columbus in his final years (he died in 1506), after a disastrous stint as a colonial administrator and a series of exhausting legal battles to collect the rewards he considered due from his 1492 royal contract.

Around Columbus’s neck on a heavy chain hangs a portrait of a woman, probably his patron Queen Isabella, who died while Columbus’s case was plodding through the courts. His right hand grasps a flagpole. Hanging from it is a flag with the arms of Spain, and it’s surmounted by a cross—reminders that Columbus made his voyage with royal authority, and for religious as well as commercial reasons.

Behind him is a capstan, used on ships to wind in rope. The globe resting on the capstan is the sculpture’s only reference to Columbus’s heroic journey beyond the bounds of the world as any of his contemporaries knew it. Why can we see all these details so easily? Because the Central Park statue’s pedestal rises a mere seven feet. This Columbus is literally more down-to-earth than the Columbus Monument, where the explorer is sixty feet above the ground.

The Central Park statue is a modified version of a marble Columbus by Suñol dedicated in Madrid’s Plaza de Colón in 1886. The Madrid Columbus stands on a tall octagonal pillar with a base in the elaborate gothic style. The base supports reliefs of the Madonna, Queen Isabella, Columbus conferring with Father Deza, and the Santa Maria, plus four life-size heralds, the arms of Spain, and a list of crew members.

Its message: that Columbus’s achievements were committee efforts, with credit going to God, the Spanish monarchs, and the crew as well as Columbus. The Central Park Columbus, bereft of his supporting cast and with only the globe and capstan to indicate his accomplishments, looks fatigued and hopeless.

In studying the Columbus Monument, we saw that subsidiary details such as reliefs and ornaments can significantly affect the theme of a sculpture. In this Columbus, let’s shift our focus and consider the effect of one particular detail: Columbus’s left hand. Is he pointing to something? Making a request? Although the gesture is very similar to Vanderbilt’s (Chapter 25; see also here), we interpret them differently, in large part due to the expression and pose of each figure.

The Central Park Columbus, old and tired, looks upward to heaven. His palm also faces upward. Holding one’s palm upward usually means one is asking for something. Hence we read Columbus as needing something, and (due to the upward glance) as asking heaven’s help to get it.

Vanderbilt, with his direct gaze, stern mouth and upright posture, seems authoritative and in control even though the portrait was sculpted when he was seventy-five years old. Given Vanderbilt’s pose and expression, the gesture of his left hand naturally seems more decisive – as if he’s issuing orders.

Even so specific a detail as having a palm facing up or down, however, doesn’t have an absolute and unchanging meaning that holds true regardless of the rest of the sculpture. Roscoe Conkling (Chapter 18, also here) has his right arm slightly extended, palm up. Yet from his easy posture, his level gaze, and particularly the way he hooks his other thumb into a pocket, he seems merely casual, as if he’s asking a rhetorical question while chatting with a colleague.

About the subject

The attitude of most late-nineteenth-century Americans toward their country was reflected in a single sentence recited by the nation’s schoolchildren: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands: one Nation, indivisible, with Liberty and Justice for all.” The Pledge of Allegiance was introduced across the nation on Columbus Day, 1892, the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. That’s appropriate because Americans’ attitudes toward Columbus, toward the United States, and toward Western civilization have always been closely linked. Washington Irving, writing in the 1820s (see excerpt at beginning of post), was one of the first to make this connection. By 1892 Columbus was regarded as an American national hero, although he never set foot on what became United States soil.

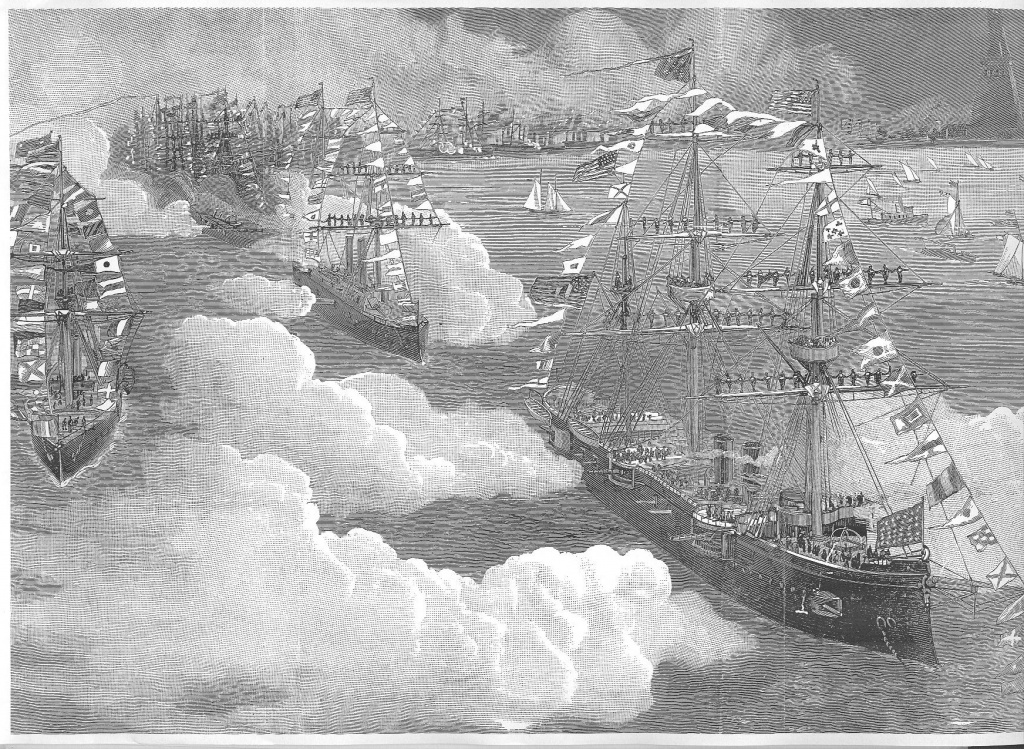

The four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage saw the dedication of monuments to the explorer throughout the United States, as well as the magnificent, six-month-long Columbian Exposition in Chicago that drew 20 million visitors. (More here.) Celebrating America’s centuries of progress in the intellectual, technological and cultural arenas, the “White City’s” 686-acre site was filled with the works of such eminent architects as Richard Morris Hunt (Chapter 38), McKim, Mead and White, and Louis H. Sullivan. The buildings and grounds were lavishly embellished with sculptures by Frederick MacMonnies, Daniel Chester French, Philip Martiny and others, under the direction of Augustus Saint Gaudens. (Links to their works here.) In the Palace of Fine Arts, twelve hundred paintings and sculptures formed the largest display of American art ever assembled. Other Columbian Exposition displays equated progress with material improvement, glorifying both.

New York lost the competition to host the Columbian Exposition, but held its own lavish celebrations.

A century later the National Council of Churches, in a widely publicized tirade, shrieked that Columbus’s arrival in the Americas brought “an invasion and colonization with legalized occupation, genocide, economic exploitation and a deep level of institutional racism and moral decadence.” Few voices rose in Columbus’s defense. The five-hundredth anniversary of his first voyage passed in 1992 with only minor tributes.

Yet the debate over whether Columbus’s voyage to the New World deserves praise or condemnation is ultimately a debate over whether Western civilization is better than the life of the pre-Columbian “noble savage”—the exhausting, brutally short life of primitive farmers and hunters in a Stone-Age culture where writing and the wheel were unknown.

The World’s Columbian Exposition

The Chicago exposition celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage is described in fascinating detail in Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City. Among the many novelties on display at the Fair was the newly invented Ferris Wheel.

Although the Exposition was temporary, its influence was long lasting. Descendants of the “White City” include the Emerald City in Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, the “alabaster cities” in “America the Beautiful,” and Walt Disney theme parks. And of course it inspired the City Beautiful movement, whose effects are still standing in New York: see Bryant. Shown in this episode to illustrate it are Alma Mater and Straus.

Artists at the Columbian Exposition

Among the artists who contributed works to the Columbian Exposition and also created works still standing in New York City are:

- Frederick MacMonnies, Nathan Hale

- Daniel Chester French, Continents, Hunt Memorial, Alma Mater

- Augustus Saint Gaudens, Farragut, Cooper, Sherman; see also his Double Eagle coin in the Theodore Roosevelt episode

- Richard Morris Hunt, architect, honored in the Hunt Memorial

- Philip Martiny: sculptures on Surrogate’s Court, Chelsea Memorial; see also From Portraits to Puddles

New York Celebrates the 400th Anniversary of Columbus’s First Voyage

New Yorkers lost the competition to host the Columbian Exposition, but erected 2 monuments to Columbus in the 1890s: this one by Sunol and Russo’s Columbus Monument.

More

- The Columbus Monument was a gift of New York’s Italian-Americans. Suñol’s Columbus was presented by the city’s well-established, wealthier residents. General James Grant Wilson, who saw Suñol’s marble Columbus in Madrid, led the drive to raise funds for a bronze replica for New York. (It was slighty modified by the artist from the marble original.) Under the auspices of the New York Genealogical Society, the Astors, Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and other prominent New Yorkers contributed $100 each toward the sculpture’s cost.

- For other sculptures of Columbus in New York City, see last year’s Columbus Day post and last week’s post on the Columbus Monument.

- For more on Columbus, see Thomas Bowden’s Enemies of Christopher Columbus. From the Amazon blurb: “In recent years, the enemies of Christopher Columbus have succeeded in damaging, if not demolishing, his historical reputation. Today, Columbus is seen not as a hero but as an inept sailor turned brutal conqueror, and his voyage is taught as the opening assault in a genocidal campaign by cruel imperialists bent on exterminating the peaceful natives who inhabited an idyllic wilderness in harmony with the environment. In this highly controversial book, Thomas Bowden challenges all of these assumptions. As he says in his introductory comments, “The real victim of the incessant attacks on Christopher Columbus is Western civilization itself.”

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.