Second in a series of several posts giving the full text of the “Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park,” 1862. The first post in the series, which includes background information, is here; third is here.

Two points struck me about this section of the “Report on Nomenclature.” First: Green credits the Park not to the beneficent government of the city and state of New York, but to the city’s industrious residents. Second: Green does his best to include all the professions he can think of … and there are so very many that weren’t even conceivable in 1862. If I were a teacher, I’d set my students to suggesting names for the Central Park gates if they were constructed today.

Here’s Green, continuing.

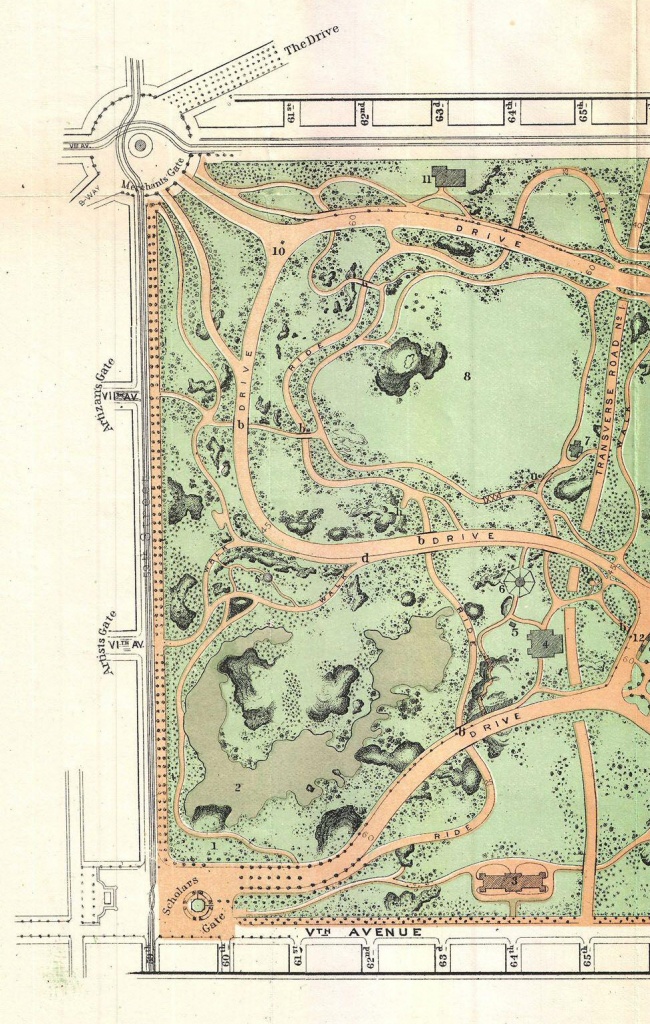

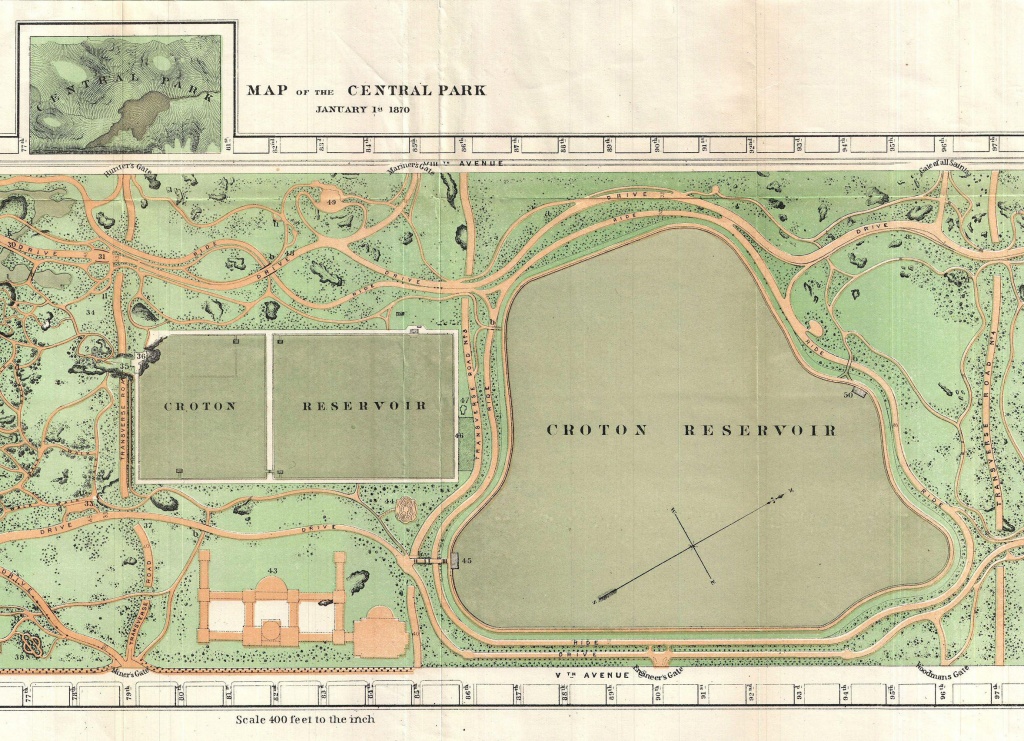

Although, as already stated, there are twenty entrances to the Park, special interest attaches to the four gateways on Fifty-ninth street, because they directly face the large portion of the city already built up, and are always likely to be the most thronged.

Their position thus seems to require that the names by which they are to be known, should collectively express a single idea that will admit of further development in detail in the other less prominent gateways.

The construction of the Park has been easily achieved, because the industrious population of New York has been wise enough to require it, and rich enough to pay for it: to New Yorkers it belongs wholly, and these four principal gateways may, perhaps, be allowed to recognize this proprietary right, and to extend to each citizen a respectful welcome.

It should, however, be remembered in this connection, that while the Park is intended as a place for freedom and relaxation, for play, and not for work, it has been constructed with no idea of encouraging habits of laziness, or in any way for the benefit of idlers and drones; it is an extensive pleasure-ground, planted conveniently in our midst, so that innocent recreation may quickly follow peaceful labor, and its paramount object is to offer facilities for a daily enjoyment of life to the industrious thousands who are working steadily and conscientiously in the great city which spreads from every direction around it. The pervading sentiment embodied both in its original conception and in all the details that appertain to its actual execution, may, in fact, be briefly expressed in the three words, “Pleasure with Business;” or, for the sake of still further generalizing the whole idea, we may take the nobler words, “Beauty with Duty.”

If an attempt is made to analyze the various industrial pursuits of a large city like New York, it will be found that they may be easily grouped under a few leading heads.

We have, first, that portion of the population whose sphere of usefulness is manual labor. This large and important class contributes to the prosperity of the community all the hard, positive, tangible work that is done, and it deserves, on entering the Park, a hearty and respectful recognition. It should scarcely be distinguished, however, by such terms as “laborer” or “mechanic,” for every laborer may bring some skill and wit to his work, and every mechanic may show some degree of taste and cleverness in the exercise of his craft: the word “Artizan,” on the other hand, seems to present the whole idea in its more comprehensive and desirable aspect, and is, perhaps, the most characteristic title that can be used.

In close connection with the industrial idea suggested by the term “Artizan,” will be found another which may be readily conveyed by the word “Artist.” The business of the artist tis to give animation and grace to the work that is done in the world, and to show that only the dull, the selfish, and the fainthearted, need to labor under the primal curse, for that work is a fruitful blessing, both in its performance and its result, whenever it is thoughtfully conceived, and beautifully executed. In this class will naturally be included all whose pursuits are directly connected with the idea of “Design,” either in the leading arts of music, painting, architecture, and sculpture, or in the numberless supplementary arts, that, with the advance of civilization, have grown out from these parent stems.

The next important generalization that suggests itself, is that expressed by the word “Merchant,” for it is necessary not only that work should be done, but that its results should be gathered together with prudence, and wisely distributed for the best advantage of all concerned; and this good office is performed by the merchant under many different names, such as “Banker,” “Broker,” “Importer,” “Trader,” “Agent,” “Director,” “Store Keeper.” The prosperity of every community must necessarily depend to a great extent on the successful development of the general idea that is embodied in these various terms, and as the city of New York is the commercial centre of the whole country, it is especially desirable that it should find an adequate recognition in connection with the Park.

There seems to be yet one other class of laborers who cannot be correctly distinguished, either by the term “Artizan,” “Artist,” or “Merchant,” and this is the class that includes the Poet, the Divine, the Statesman, the Lawyer, the Author, the Editor, the Teacher, the Physician, the man of Science, and all in fact, whose contributions to the welfare of the community, are of a specially intellectual character.

The word “Scholar,” perhaps expresses the generic idea with sufficient completeness, and if we add this term to the three already mentioned, we have a group of four names bearing a mutual relation one to the other, and embodying in a general way, and on an equal footing, so far as the Park is concerned, all the industrial ideas that are entertained in a civilized community.

In the remaining gates, the dependence of the city on the whole country may be recognized, and its connection with other cities and other countries acknowledge; the importance of the domestic relations may be dwelt on, and the idea may be set forth that for the sake of peace, we must yet be prepared for war.

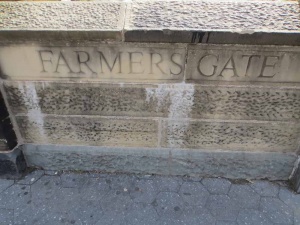

The first industrial idea outside of the city that seems to demand our attentive consideration, is that connected with the cultivation of the soil, for the sustenance of the metropolis is entirely dependent on agricultural labor, and it could with difficulty afford to be deprived, even for a day, or the supplies it is constantly receiving from this prolific source. The occupation of the agriculturalist, is divided into many different branches, but all have sprung from the discovery that the most valuable products of the earth, both animate and inanimate, must be brought to perfection by careful culture, before mankind can reap from them the full advantage they are capable of yielding. This generalization would naturally include all the labor that is devoted to rural pursuits, and its representatives would be the farmer, the grazier, the planter of grain, flax, hemp, rice, cotton, sugar, and tobacco, the fruit-grower, and the gardener.

In the choice of a single term that may express in a suitable manner the various ramifications of agricultural labor, it is perhaps worth while to give especial prominence to the fact already mentioned, that the city is provided with its seemingly exhaustless supplies of food and raiment, almost entirely through the patient care and prudent foresight of the tiller of the soil, and if it is desired to lay particular stress on this characteristic idea of providence and forethought, it seems to be more simply and completely conveyed by the familiar word “Husbandman,” than by any other term. If, however, it is preferable to express only the general idea of cultivation, this entrance may take the name of the “Cultivator’s” gate, or the “Agriculturalist’s” gate.

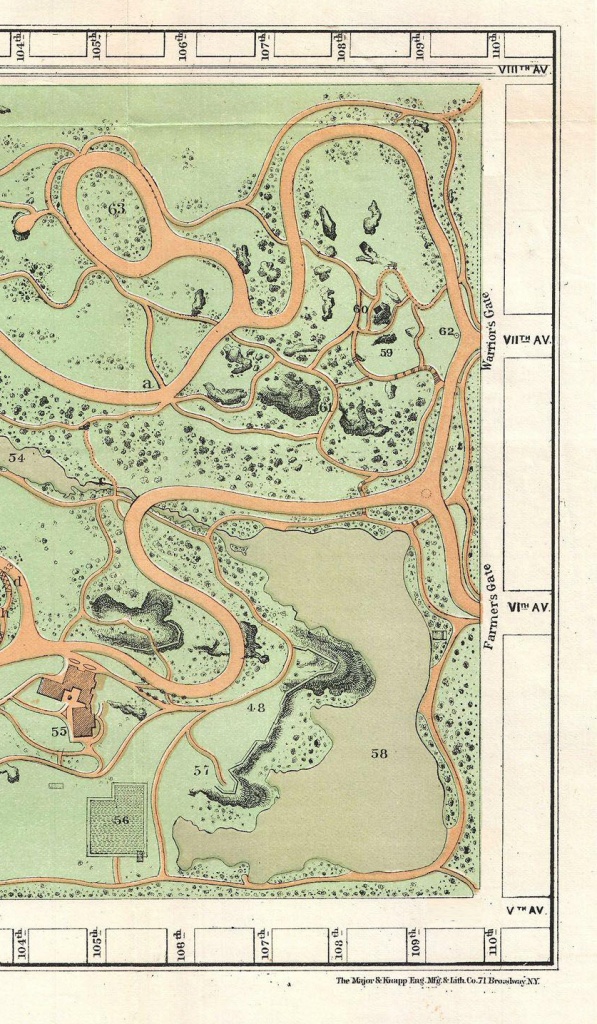

In the event of the plan being carried out which was suggested some time since for widening to one hundred and fifty feet the Seventh avenue, north of One hundred and tenth street, and planting it with several rows of trees; the point at which this shaded country-like road will meet the Park, seems to be the most appropriate for the gate intended to be illustrative of country life.

Having thus given due prominence to the preeminently peaceful pursuits of agriculture, it is fitting that proper respect should be paid to the stern truth that peace is not always possible, the strong arm of the soldier being at times absolutely needed to sustain the whole frame-work of society, and to secure freedom of action not only to the cultivator of the soil, but to all other peaceably disposed and illustrious members of the body politic. [NOTE: Green wrote the “Report on Nomenclature” during the third year of the Civil War.]

It is evident, indeed, that every well organized community must contain within itself the elements of an army prepared, whenever the necessity arises, to strike boldly in defence of its just rights, and without doubt the claim of the “Warrior” to the grateful recognition of the city of New York will be at once allowed.

The “Warrior’s” gate may, with propriety, be situated on the north side of the Park, facing Washington Heights, and in the immediate neighborhood of the old fortifications, that will continue to be preserved within the boundaries of the people’s pleasure-ground. [NOTE: He’s referring to the Blockhouse.]

The vocations which are followed by men who find in untamed and uncultivated nature a suitable field for action, are so various, that they required to be grouped under several distinct heads.

Thus we have the “Hunter” and the “Fisherman,” both individual pursuits that contributed largely to the wants of the community.

The term “Woodman” may represent all the labor that is devoted to procuring such important staples as lumber, bark, charcoal, pitch, tar, rosin, and turpentine; and the term “Miner” seems to include the workers in coal, and the different ores, and also the quarrymen or miners of stone.

The prosperity of every metropolis depends to an important extent on the channels open to it for ready communication with the rest of the business world. In a city with such an immense shipping interest as New York, one branch of this idea will by typified by the “Mariner,” who is forever carving out a new public highway over the ocean, the river, or the lake, and the other equally important branch will be represented by the “Engineer,” who provides the community with all the facilities it possesses for overland transportation, and also contributes to its welfare in many other ways. The highroad, the plankroad, the railroad, the canal, the breakwater, the dock, the tunnel, the viaduct, the aqueduct, and the reservoir are all called into existence by his skill and indomitable perseverance, and there can be no question but that the general ideas conveyed by the terms “Mariner” and “Engineer,” deserve a ready appreciation in connection with such a public work as the Park.

The Mariner’s gate should perhaps be situated in the immediate vicinity of the highest ground contained within the Park limits, so that on entering or leaving it a suggestive view may be offered of the hills beyond the harbor in the distance, and of the two busy rivers that float by the city.

The Engineer’s gate may with some propriety be placed on the east side of the new reservoir, where “Beauty” cheerfully gives way to “Duty,” and the good cause of temperance and cleanliness requires that the plan of the people’s pleasure-ground shall conform closely to the lines of an equally popular, but more strictly useful, engineering work.

Having thus generalized all the preeminently practical pursuits of life, and acknowledged the obligations that the city is under to those who follow them, it is fitting that a welcome should be extended to …

[More to come next week]

More

- Part 1 of this series is here.

- Note on apostrophes: in theory, all the names should be plural possessive: the gate of the artisans should be the “Artisans’ Gate”. In my photos of inscriptions, it’s sometimes difficult to be sure whether there’s an apostrophe or where it is. I’ve standardized the names in the captions.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.