First in a series; second is here, third is here.

In 1898, Andrew Haswell Green was proclaimed “Father of Greater New York” for his efforts to see Manhattan consolidated with the patchwork of forty-odd cities, towns, and villages that now make up the Outer Boroughs. But back in 1857, thirty-seven-year-old Green, a real-estate lawyer, was working on a smaller scale. He was one of the eleven members of the first Board of Commissioners of the Central Park.

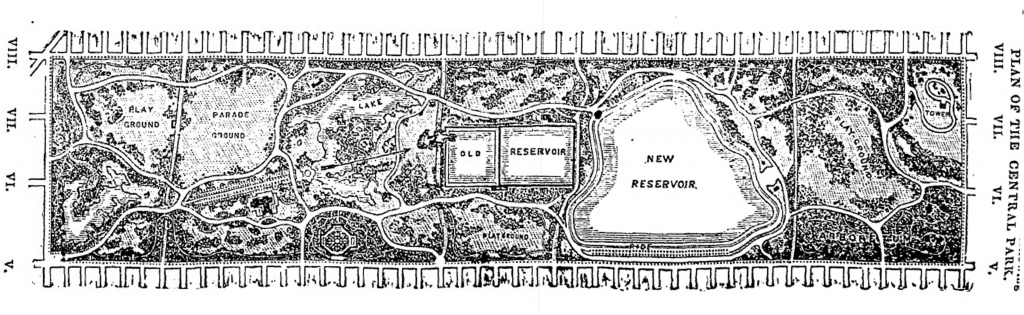

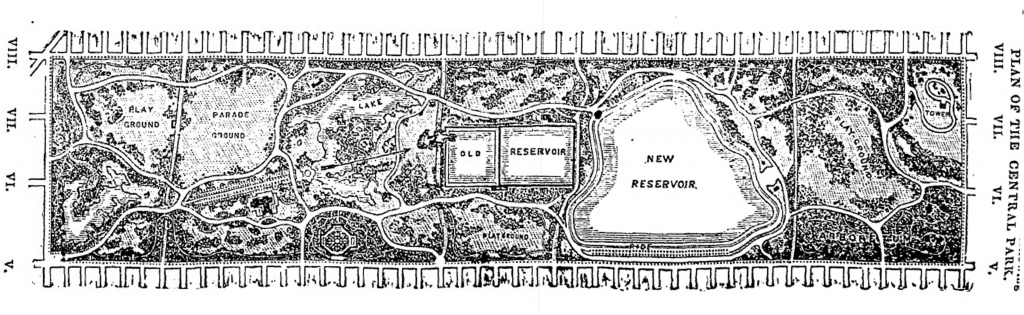

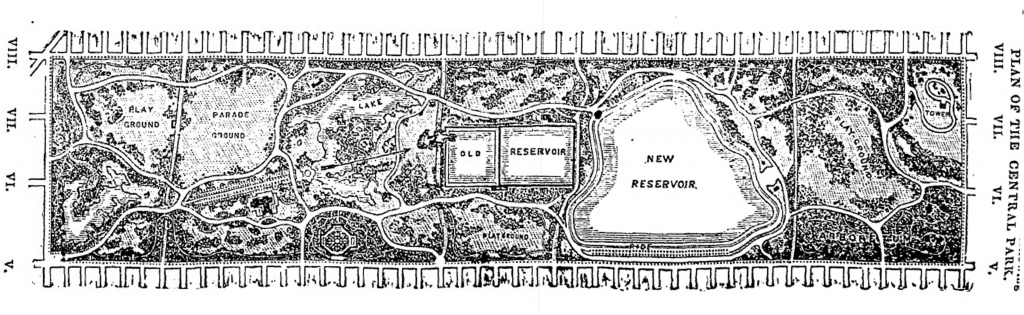

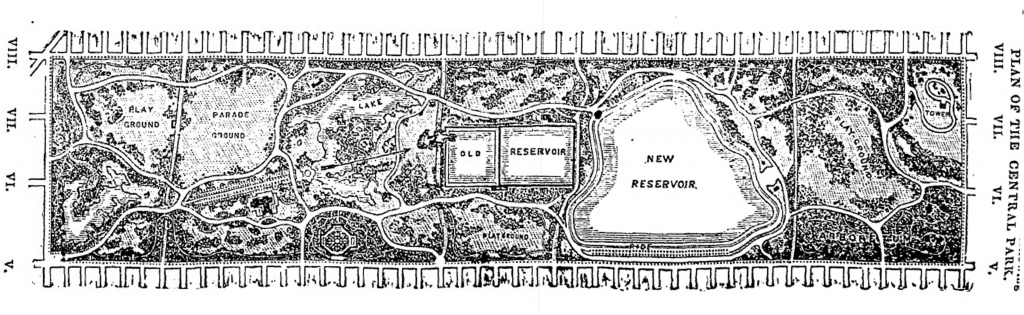

By 1863, implementation of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Greensward Plan was well on its way. The grounds, drives, and walks south of 102nd Street were open to the public.

Green was by this time park comptroller. Olmsted, the Park’s architect-in-chief, resented Green’s tight grasp of the financial reins: “Not a dollar, not a cent, is got from under his paw that is not wet with his blood and sweat” (private letter quoted in Rosenzweig and Blackmar, The Park and the People p. 191). But Green’s fiscal savvy combined with Olmsted and Vaux’s design and administrative skills made the Park the best-run public work in the United States.

With the lower part of the Park nearly complete, the Standing Committee on Statuary, Fountains, and Architectural Structures of the Board of Commissioner submitted a report on names for the entrances to the Park. The “Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park” was signed by H.G. Stebbins, C.H. Russell, and Andrew H. Green. Its style, however, is characteristic of Green, as is the content: a long historical introduction followed by a detailed exposition of his own ideas. The “Report” was printed in Minutes of Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park for the Year Ending April 30, 1862, pp. 125-136 (here: scroll to search result on p. 125). For this series of blog posts, I’m cutting the “Report” into sections and adding illustrations.

In the introduction (below), Green argues that the gates need names. If we don’t assign them, common usage will create them, and they might be odd or soon outmoded. He discusses the limitations for the gates of Central Park (we must have enough names for 20 gates) and eliminates some possibilities (victories, states, prominent men). Green’s own proposal will appear in the next post.

“Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park”

To the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park:

The Standing Committee on Statuary, Fountains, and Architectural Structures, to whom was referred the subject of the nomenclature of the Park, respectfully report:

That the lower Park having now assumed its final shape, and the different avenues leading to it being in such an approximate stage of forwardness, as to admit of an early completion of the various entrances that directly connect the city with this portion of the work; special designations are much needed for the gateways, and the proper time seems to have arrived for a final consideration of this interesting part of the general design.

That the Park is to be enclosed, seems to have been assume in the action of the Board, although the intention is not yet expressly declared.

There are examples of Parks, in populous cities, without enclosures; but the necessity for a permanent enclosure to the Central Park, for the preservation of order and the protection of property, can hardly be questioned.

The character of this enclosure, as yet undetermined, will necessarily be decided by the extent of means at the disposal of the Board; but whatever style or material may be adopted, it is evident that entrance ways will be required at proper intervals, and preparation has accordingly been made for them in the general arrangement of the design.

These entrances are twenty in number, some of more immediate importance, and others destined always to be in a measure subordinate, because of the lesser currents of ingress and egress that they are designed to accommodate, but all requiring to be arranged with primary respect to the public convenience, and with a certain degree of architectural fitness.

Immemorial custom has sanctioned the practice of giving names of dignity to the gates or entrance-ways of cities, which, in ancient, as in more modern times, were walled.

The gates of ancient cities were places of great military and civic importance; through them the people poured to their agricultural or pastoral pursuits, to return again for protection at night.

In Hebrew cities, and probably in those of other Eastern nations, they were places of meeting or appointment for business transactions, and, as the great mass of the people passed through them, they were convenient points for this purpose. They were also assembling places, and the elders sat at the gates to administer summary justice. They were places as well of judgment as of execution; they seem to have been places where proclamations or notices were made to the people, and were places of resort for those purposes for which people generally assemble.

The practice of giving names to these gates is almost as ancient as are the records of history. Names were sometimes, as we learn from the many examples in the Scriptures, drawn from local circumstances, as the Corner Gate, the Valley Gate, the Prison Gate, the Gate of the Fountain, the Water Gate, the First Gate, the Middle Gate: sometimes from conspicuous dignitaries to whose use they were especially assigned, and which were considered gates of especial honor, as the King’s Gate – “to stand in the gate of the children of the people, whereby the Kings of Judah come in, and by which they go out;” sometimes from the points of the compass, as the North, East, South, West Gate; sometimes they were given in honor of tribes of people, as the Gate of Benjamin – “the gates of the city shall be after the names of the tribes of Israel;” sometimes the name was drawn from the business transacted in the vicinity, as the Horse Gate, the Sheep Gate, the Fish Gate, the Dung Gate.

The word “gate” has also become the representative of power and dominion, as “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it,” and the perfect security and peacefulness of the Heavenly City is beautifully described when it is said “the gates of it shall not be shut at all by day, for there shall be no night there.”

The custom of designating gates by distinct names has been continued in mediaeval and in more modern times, and its universality denotes the existence of a necessity which will find some mode for its satisfaction.

The naming of cities, of rivers, and of all geographical features, originates in a similar desire for an easily recognized and popular title; and streets, places, and houses also require to be conveniently name, because the popular demand insists on a brief, apt and convenient designation for all localities to which general resort is had.

A local circumstance of feature that has determined the name of a locality often fades away before improvement, leaving the name without any apparent reason for it; but it is difficult to effect a change in the name, although the circumstance or incident that gave rise to it may have passed entirely out of mind, because it has a recognized place in the popular vocabulary, from which it cannot, without great inconvenience, be dislodged; it has, perhaps, entered into the literature of centuries; it has been used as a means of description on conveyances, or other legal documents, and in so many ways become useful, that a change would lead to serious embarrassment.

The same considerations that give names as convenient designations of locality to the gates of cities, obtain in a great place of public resort like the Park, and the popular convenience will manage somehow to affix local names that cannot readily be effaced, unless appropriate ones are suggested, and supplied in season by the proper authorities.

There is indeed already growing up a catalogue of designations of localities about the Park, that will quietly take possession of the field, unless other provisions are made.

While this question of nomenclature requires careful adjustment in connection with every part of the Park, its importance is more particularly evident in the case of the entrance gateways, as they will naturally attract a large share of public attention, and be constantly spoken of by name, on account of the conspicuous purposes they serve, and the prominent position they occupy; it is therefore desirable, not only that they should be made as agreeable as possible in design, but that they should be named in accordance with some simple but comprehensive plan that will fully meet the every-day wants of the public, and at the same time be unobjectionable in other important aspects.

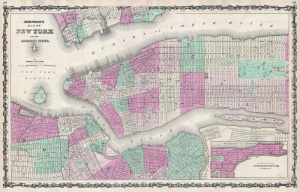

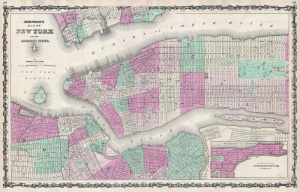

The monotonous numerical system used to distinguish the thoroughfares of New York is at once felt to be unsuitable for Park use, and but few suggestions of much greater value appear to be offered by other metropolitan cities.

In London, for example, we find that as no provision for names was made, nicknames like Billlings-gate, Aldersgate, Cripple-gate, and High-gate, have been allowed to pass unquestioned into general use. In Paris, on the other hand, more care has been taken in the first instance, and titles like Porte St. Denis and Porte St. Martin have been given to the different city gates; but the idea thus embodied can hardly be considered appropriate for use on the Central Park.

The plan often adopted in Europe of commemorating some brilliant victory in the name given to a new public work, possesses considerable attractions, and the Pont D’Arcole, the Rue de Sebastopol, Waterloo Bridge, and Trafalgar Square, seem to be well named: it is a plan, however, somewhat unsuitable for adoption in a public pleasure ground, that is especially intended for recreation and repose, and which should, therefore, rather speak of peace and good-will than of sanguinary contests.

Several other suggestions naturally occur that are more or less worthy of consideration in such a situation.

Thus, the names of the different States of the Union, or of the important cities, or of the most prominent men, may be used; but with all propositions of this and of a kindred nature the difficulty at once arises, that the opportunity is insufficient to fairly exhaust the subject, and that every selection, however carefully made, is liable to the objection that it will seem partial and invidious.

It will, moreover, in all probability, be thought desirable that the Park itself should, in some way, indicate the special nomenclature to be used; it may, therefore, be worth while to consider whether it offers any leading ideas of sufficient scope and general interest to deserve expression in the names of the different entrances, and of a character that will readily admit of varied artistic treatment in the gateways themselves.

Although, as already stated, there are twenty entrances to the Park, special interest attaches to the four gateways on Fifty-ninth street, because they directly face the large portion of the city already built up, and are always likely to be the most thronged.

Their position thus seems to require that the names by which they are to be known, should collectively express a single idea that will admit of further development in detail in the other less prominent gateways.

[Continued in the next post]

More

- The annual reports of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park (and other government entities who were in charge of it) beginning in 1857, are here. A list of the members of the Board of Commissioners form 1856 to 1870 is here. I’ve called the Board that took office in April 1857 the first “Board of Commissioners,” because the previous governing body consisted only of Mayor Fernando Wood and Street Commissioner Joseph S. Taylor.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.