In 2023, I emailed 215 art-related items to supporters of my Sunday Recommendations list. This week: my favorites in painting and sculpture. This post is available as a video at https://youtu.be/-cqL9TuZS2w .

Painting

Top picks (5 of them, in no particular order)

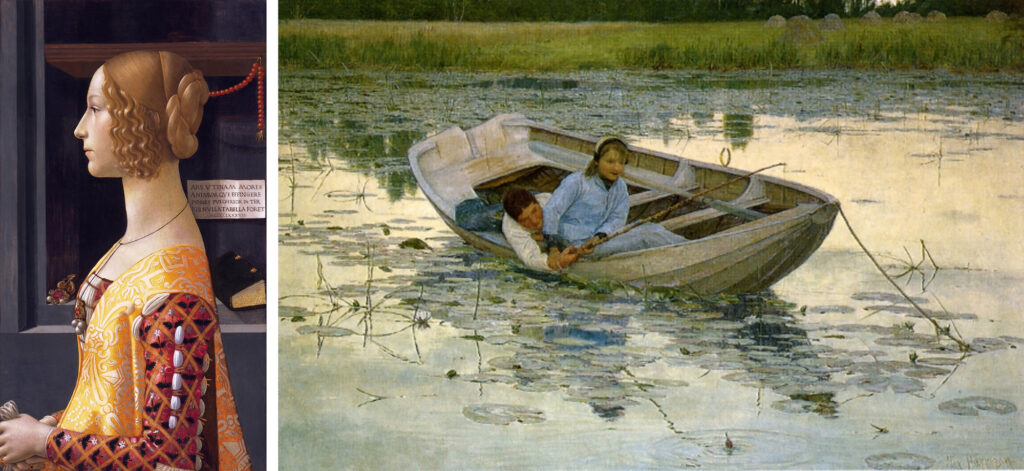

1. Ghirlandaio, Domenico (1448-1494). Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid) (ca. 1489-1490). A lovely and evocative Renaissance portrait. Italian artists of this period were looking to Roman models, and profile portraits on coins were among the few surviving Roman artifacts. No Roman paintings were available as illustrations of color, shading, or light, so we can also see how much progress Renaissance painters had made, on their own. (See Innovators in Painting, Ch. 16 & following). Even more importantly, though, this painting shows how much views of man and life on earth have changed since the Middle Ages. Lorenzo Tornabuoni, a prominent Florentine banker, commissioned this portrait after his beautiful young wife died in childbirth. Giovanna is represented as she was when alive: pious (her prayer book is behind her), but with elaborately dressed hair, expensive clothes, and bejeweled accessories. The words on the trompe l’oeil note behind her are adapted from the Roman poet Martial (d. ca. 102 AD): “Ars utinam mores animum que effingere posses pulchrior in terris nulla tabella foret MCCCCLXXXVIII” (“Art, would that you could represent character and mind! There would be no more beautiful painting on earth. 1488”). Domenico Ghirlandaio didn’t have the innovative genius of his contemporaries Leonardo and Raphael. He did, however, run the largest painting workshop in Florence, and it was to that workshop that 13-year-old Michelangelo was sent to learn to paint. He was probably there when Ghirlandaio painted this portrait.

2. Harrison, Alexander. The Amateurs (1882-1883). A charming work exhibited at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, now at the Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso University, Valparaiso, Indiana. I love the way the light hits the water, and I’m waiting breathlessly to see if these two will capsize the boat. I spoke about this and other paintings displayed at the Columbian Exposition in one of the sessions of the Resurrecting Romanticism conference in October 2023; check the Books & Essays page to see if the video of that talk is available yet.

3. Raphael. Baldassare Castiglione (ca. 1514-1515). Raphael made 2 major contributions to the progress of painting (see Innovators in Painting Chs. 23 & 24), and was also an extremely competent portrait painter. His portrait of Castiglione was enormously influential: copies exist by Rembrandt, Rubens, and Matisse, and others. Castiglione, a diplomat, humanist, and long-time friend of Raphael, was the author of Il Cortigiano, 1528, an etiquette book that instructed courtiers and would-be courtiers on the manners, physique, courage, education, and dress expected in high-class circles. Il Cortigiano was translated to 6 languages during the 1500s, and was one of the most widely read books of that century. The book popularized the term sprezzatura, an effortless grace that befits a man of culture: as Castiglione put it, “a certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it.” Cyrano de Bergerac, James Bond, Percival Blakeney, and Roger Federer have sprezzatura; so does Robinson’s Flammonde.

4. Titian. Bacchus and Ariadne (1522-1523). For me, this painting isn’t about Bacchus and Ariadne, about Greek mythology, or even about love at first sight (which happened to Bacchus in this particular myth). It’s about the idea that even when things are at their worst – when your lover has, for example, sailed off on a ship that’s now a mere speck on the horizon – the world is still shining and beautiful, and the most unexpected delights may be right around the corner. Titian (active ca. 1506-1576) was one of the most successful painters in 16th-century Europe. This and other paintings of his early career show the brilliant, shimmering colors characteristic of the Venetian school, which included Giovanni Bellini, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

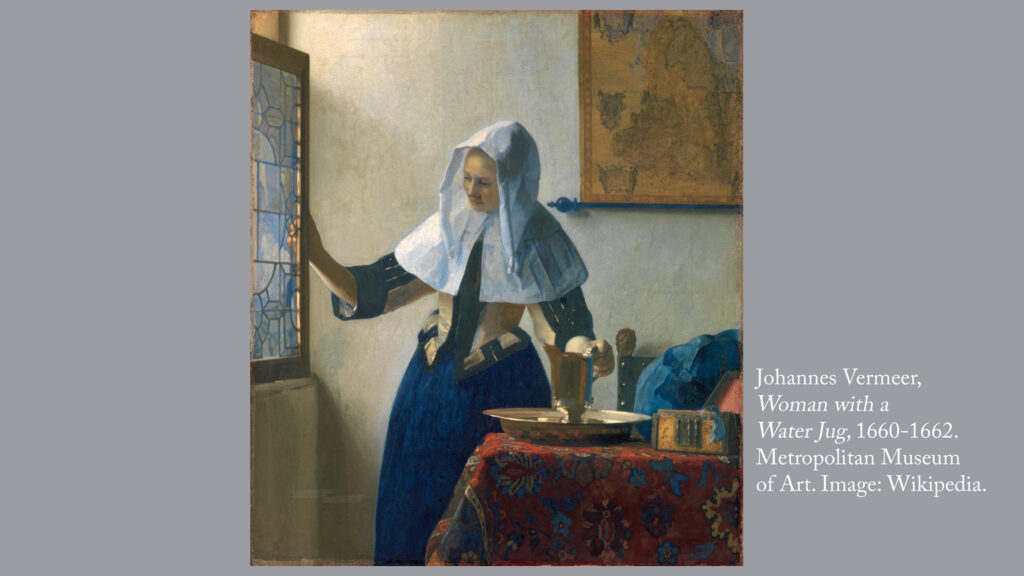

5. Vermeer, Johannes. Woman with a Water Jug (1660-1662). This is one of my favorite Vermeers: a world of quiet, glittering peace. Ayn Rand praised Vermeer (1632-1675) more highly than any other painter:

The closer an artist comes to a conceptual method of functioning visually, the greater his work. The greatest of all artists, Vermeer, devoted his paintings to a single theme: light itself. The guiding principle of his compositions is: the contextual nature of our perception of light (and of color). The physical objects in a Vermeer canvas are chosen and placed in such a way that their combined interrelationships feature, lead to and make possible the painting’s brightest patches of light, sometimes blindingly bright, in a manner which no one has been able to render before or since.

Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto p. 48

This painting is a tour de force of light: look at how it behaves differently when it hits the pitcher, the window panes, the wall, and the woman’s headdress.

Woman with a Water Pitcher was the first Vermeer to come to America. It was purchased by Henry Marquand, who commissioned the remarkable piano designed by Alma Tadema that I recommended on 8/20/2023. Marquand bequeathed the painting to the Metropolitan Museum.

Runners-up (also 5, also in no particular order)

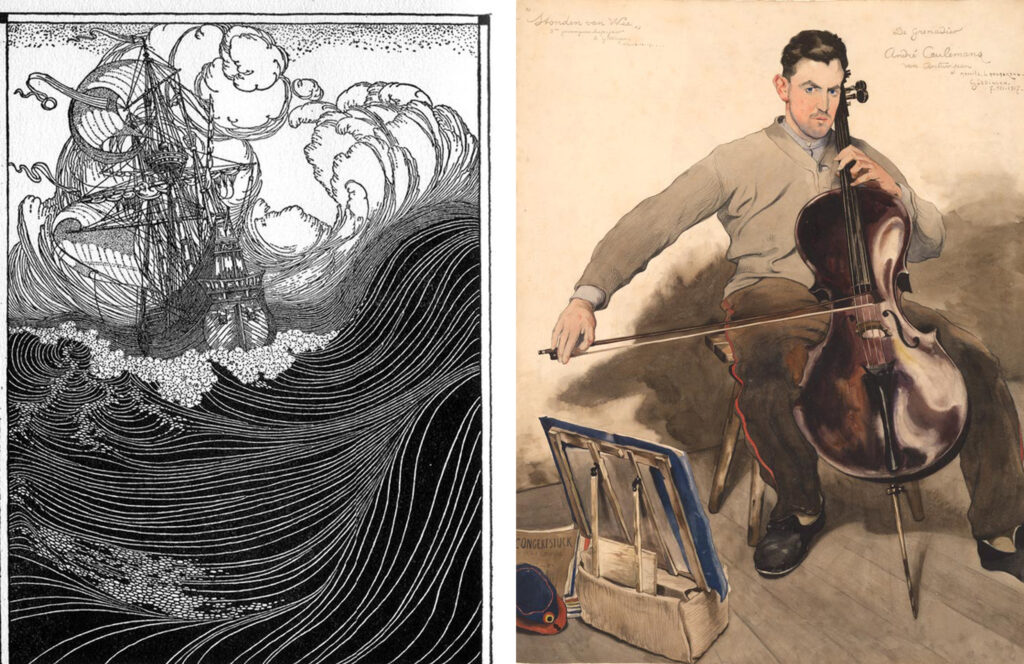

1. Walker, Dugald Stewart (1883-1937). Illustration for John Masefield’s “Sea Fever” (1926). Riffing on the Wanderlust theme: look at the swooping, curving lines of this pen and ink drawing. Can’t you feel the movement of the sea? This illustration is from Rainbow Gold: Poems Old and New Selected for Boys and Girls. The collection was edited by Sara Teasdale, whose poems (such as “Barter“) I’ve often cited in these recommendations.

2. Langaskens, Maurice. The Grenadier André Coulemans (1917). If you’re one of my supporters, you don’t need me to point out how crucial art is to survival … but here’s an example of a lovely work of art produced when bare survival was difficult. In 1914, the Germans proposed to invade France not via their shared border but via Belgium and the Netherlands. Langaskens (1884-1946) joined the Belgian army, and was almost immediately captured and thrown into a prisoner-of-war camp. He’d been a prisoner for 3 years by the time he did this portrait of a cellist who was a fellow prisoner of war. The painting (33 x 27 inches) is in watercolor, colored pencil, and graphite. More on art during World War I here.

3. Bruegel the Elder, Pieter. The Hunters in the Snow (1565). In the 1560s, Bruegel the Elder painted a series of works representing the seasons. Five of them survive, including this one at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, and The Harvesters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which I recommended back in 2021. Bruegel lived in Antwerp, a major commercial and publishing center in his day; but even a “major” city wasn’t far from the country in the 1500s. I love Bruegel’s “seasons” landscapes because they’re full of busy, purposeful people, but the people are always worked into a composition that’s based on the sweeping lines of the landscape. See my discussion of The Harvesters on p. 12 of Sunny Sundays.

4. Thaulow, Frits. Picquigny (1899). Just the sight of this river makes me feel cooler. Thaulow (1847-1906), a Norwegian, did superlative depictions of eddying water: see the Gallery on his Wikipedia page.

5. Dahl, Johan Christian. An Eruption of Vesuvius (1824). The works of Norwegian Johan Christian Claussen Dahl (1788-1857) remind me of those of those of his friend Caspar David Friedrich. When the ruins of Pompeii were discovered in 1748, Europeans became fascinated with the power of Vesuvius. It was a regular stop on the Grand Tour for noble or wealthy young men. Dahl witnessed an eruption in 1820 and painted at least 7 versions of it. This one, with two elegantly dressed visitors watching the spectacle, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Volcanic eruptions were the sort of natural events that Edmund Burke was referring to when he wrote A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful in 1757. That work is often credited with starting the Romantic movement, which was in part a reaction to the calm dignity of the Neoclassical style.

Sculpture

Tied for winner (2 works)

1. Donatello. St George for Orsanmichele, now in the Bargello Museum, Florence (1417). Donatello rediscovered many of the major innovations that had been lost since the Fall of Rome. For example: he designed sculptures meant to be viewed from all sides. He cast life-size figures in bronze. He created art for the sake of art, not for purely didactic purposes. Donatello’s own major innovation was to rethink every subject he chose to sculpt, from the Madonna to St. John the Evangelist, from Herod’s Feast to Mary Magdalen. (More discussion of these in Innovators in Sculpture, Ch. 8.) For St. George, Donatello relegated the dragon-slaying to a small relief on the base. By doing so he makes the focus of the sculpture not the fight, but St. George’s state of mind before he sets out to fight. The frown and the direction of his gaze suggest that he’s focused and wary; the tension in the body suggests he’s vigilant and ready to move. This is a new type of hero: a thinking man about to become a man of action. A hundred forty years later, Vasari wrote of the St. George:

The brightness of youthful beauty, generosity, and bravery shine forth in his face; his attitude gives evidence of a proud and terrible impetuosity; the character of the saint is indeed expressed most wonderfully, and life seems to move within that stone. It is certain that in no modern figure has there yet been seen so much animation, nor so life-like a spirit in marble, as nature and art have combined to produce by the hand of Donato in this statue.

Vasari

And yes, Michelangelo did know this work when he created his David.

2. Bernhardt, Sarah. Self-portrait as a chimera (inkwell) (ca. 1879). When she was in her late twenties, Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) was chafing at being cast only in minor roles. As a way to blow off steam, she began learning to sculpt. In 1874 she landed a supporting role in Octave Feuillet’s The Sphinx. She soon took over the lead role, portraying a woman who commits suicide by using a poison ring in the shape of a sphinx. As a nod to her big break, Bernhardt sculpted this self-portrait as a sphinx or chimera, with the body of a griffon, wings of a bat, and a dragon’s tail. I assumed at first glance that she was thinking of herself as a monster … but in fact, she’s referring to her ability to transform herself. The clue: she’s put a mask of tragedy on one shoulder, a mask of comedy on the other. Bernhardt wrote: “Once the curtain is raised, the actor ceases to belong to himself. He belongs to his character, to his author, to his public. He must do the impossible to identify himself with the first, not to betray the second, and not to disappoint the third. (The Art of the Theater, 1925.) This small bronze is not just a self-portrait, but a functional inkwell with a stand for a quill. On tours in America, Australia, and elsewhere, Bernhardt would often have a cast of the inkwell put on display in the theater lobby. I first saw one at the Clark Institute in Williamstown, MA. The Clark’s short video about it is here.

Runners-up (3 works)

1. Houdon, Jean-Antoine. Robert Fulton (1804). Plaster model of one of the last Americans to be sculpted by Houdon (1741-1828), who had already created portraits of Washington, Franklin, and other Founding Fathers. When he sat for this portrait, Fulton was in France trying to raise funding for a submarine. The Clermont, his steamboat, was still a few years in the future.

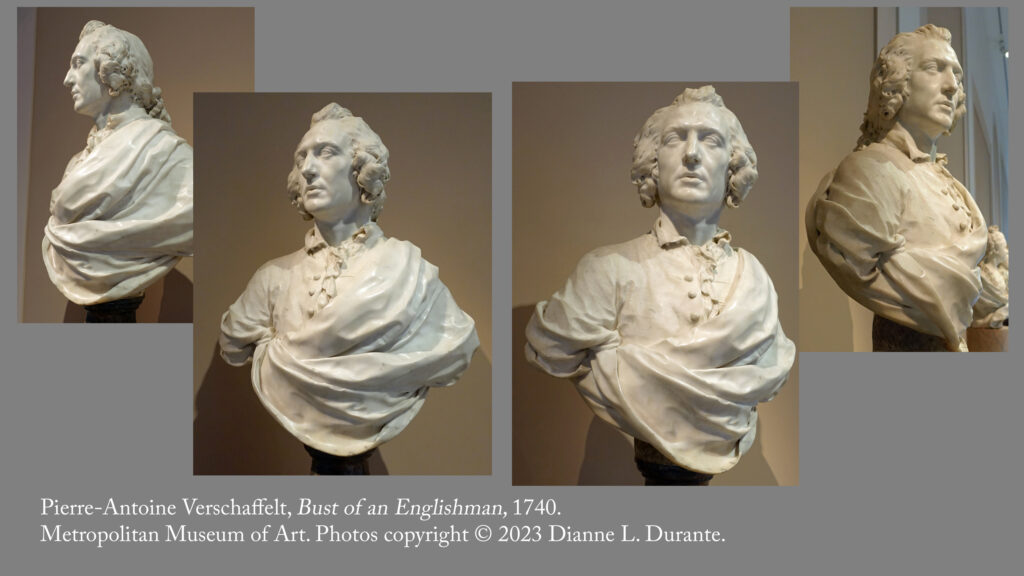

2. Verschaffelt, Pierre-Antoine. Bust of an Englishman (1740). The good thing – and also the bad thing – about institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art is that they have as many items in storage as on display. After decades of visits, I still often discover artworks that I’ve never seen before, and that are not new acquisitions. As of June 2023, this bust was at the end of a row of Rococo portrait busts in the Petrie Court. The modeling of the planes of the face is superb, and the personality intrigues me much more than the busts nearby. Verschaffelt – a truly international artist – was born in Ghent (modern Belgium) in 1710, and educated in France. He created this bust during a 14-year sojourn in Rome (1737-1751), then spent the remaining 40 years of his life in Mannheim, Germany, as court sculptor to the Elector of the Palatinate. After seeing the MMA’s bust I went looking for more of Verschaffelt’s works, but it turns out they are mostly rather mundane allegorical and mythological figures for the gardens of the Elector’s palaces. So I have to wonder: did Verschaffelt end up in Mannheim because he actually liked doing that sort of work, and found someone willing to pay him for it; or was he willing to do that sort of work for the sake of having a patron and a reliable income?

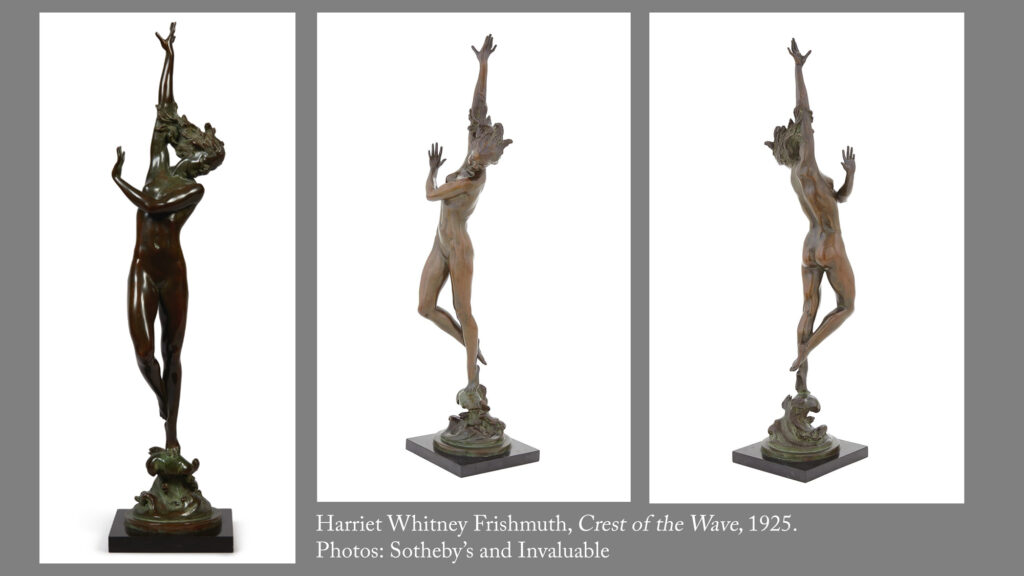

3. Frishmuth, Harriet Whitney. Crest of the Wave (1925). One of Frishmuth’s delightful, energetic sculptures. More on Frishmuth here and here. Small versions of this work come up regularly at auction: Sotheby’s sold one in early 2022 for $18,900.

Next week: Favorite Recommendations for 2023 in Architecture and Museums.

More

- A quick summary of what I did in 2023: At the Resurrecting Romanticism conference in Spartanburg, SC, in October 2023, I gave a talk on Romanticism and painting (1.25 hrs.) and another on painting at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago (.5 hours). I also participated in a panel discussion, “Nurturing the New Romantics”. These will eventually be available as videos. When they are, links will be on the Books & Essays page.

- Subscriptions from supporters are also helping me work on two books that will appear in 2024: Getting More Enjoyment from Paintings You Love (companion volume on sculpture here), and Timeline 1700-1900 (a prequel to Timeline 1900-2021).

- For my writings in 2022 and earlier, see the Books and Essays page. All my books are available in Kindle and/or print format via my Amazon author page, and via Ingram at major booksellers such as Barnes and Noble. And check out dozens of videos on my YouTube channel.

- For favorites recommendations from earlier years, see the Favorite Recommendations and Photos link.

- Want wonderful art such as these recommendations delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my Sunday Recommendations list: details here.