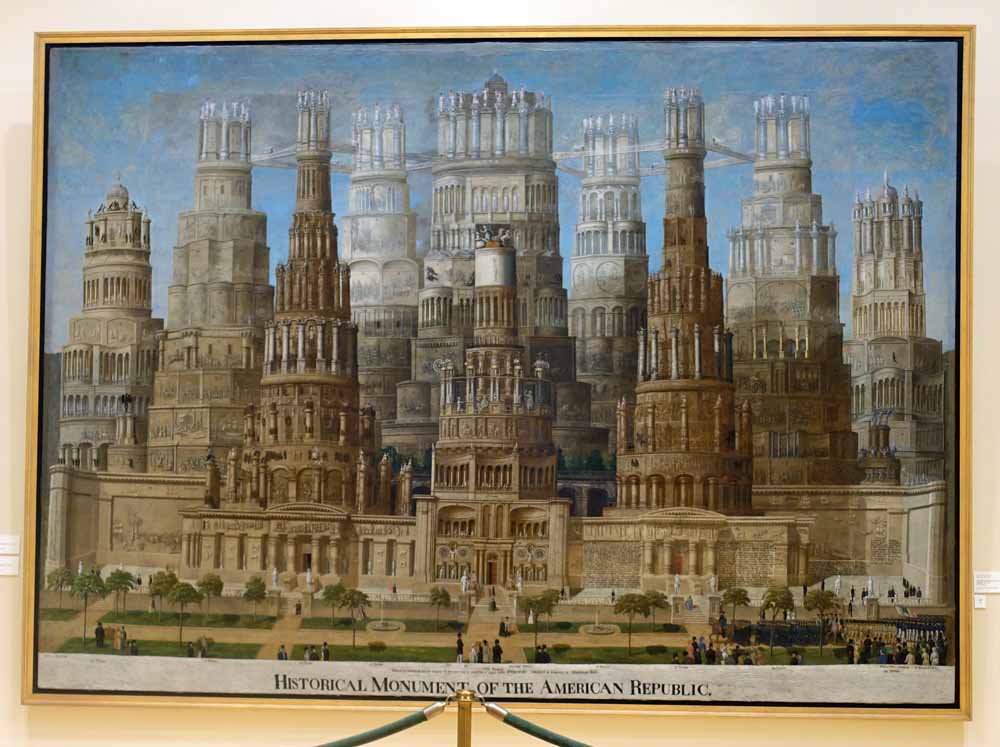

In my weekly email of Sunday Recommendations, I promise “art-related suggestions meant to inspire, to provoke wonder or thought, or simply to amaze by sheer beauty.” The Historical Monument of the American Republic by Erastus Salisbury Field falls into the “provoking wonder” class. Here’s why I couldn’t resist making trip to Springfield, Massachusetts, to see it:

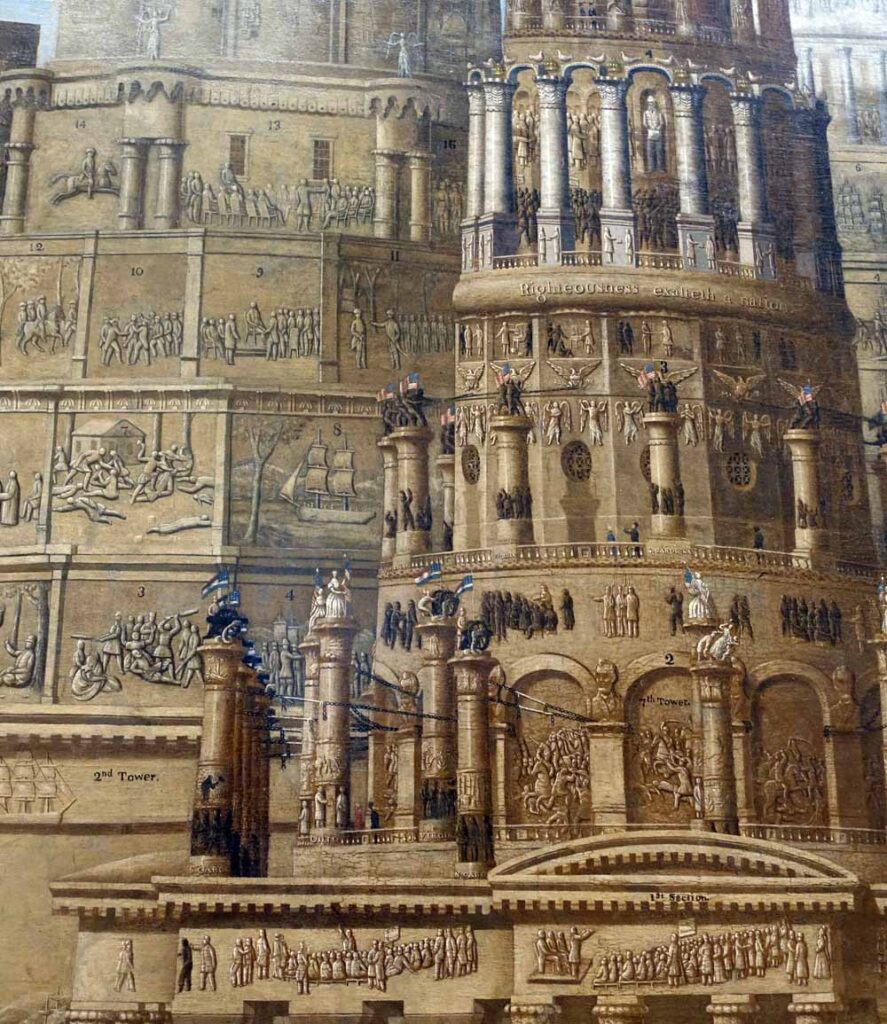

- It’s enormous: 9 feet wide, 13 feet high.

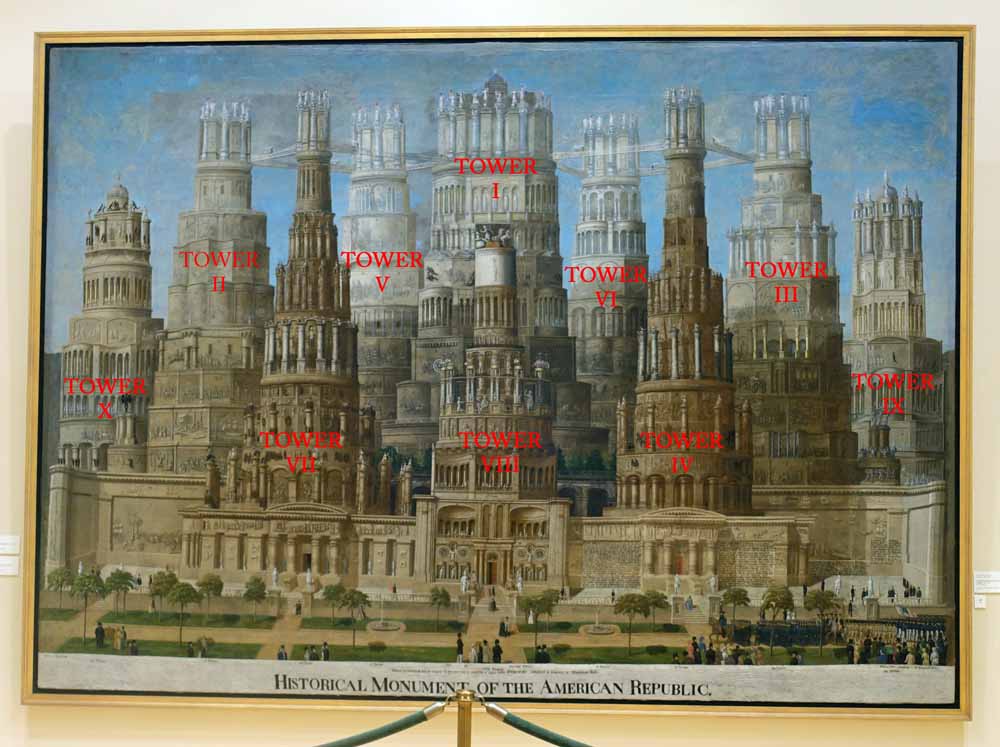

- It shows a 500-foot-high cluster of towers with steam-powered trains running between their tops.

- The artist aimed to represent the whole history of the United States, from the settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, to his own time.

Here is the Historical Monument in its current home, the Michele & Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, part of the Springfield Museums complex.

I have argued quite often that art shouldn’t be didactic – that its purpose is not to teach a historical narrative, but to present the artist’s view of what’s important. (See the chapters on medieval art in Innovators in Painting and Innovators in Sculpture.) Field’s Historical Monument is miles across the line into being didactic … but as history presented by a painter with a very distinctive viewpoint, it’s fascinating.

Erastus Salisbury Field

Field (1805-1900), a native of Leverett, Massachusetts, traveled to New York City in 1824 to study with Samuel Morse. Before Morse invented the telegraph he painted portraits of such celebrities as General Lafayette, John Adams, and James Monroe. Field was in Morse’s studio only a few months before Morse’s wife died and Morse closed his studio. Field returned to Massachusetts, becoming an itinerant artist who painted hundreds of portraits for middle-class families who couldn’t afford the likes of Morse. He never did learn to show anatomy properly: the proportions of his figures are odd, and they move awkwardly. He also had a penchant for symmetry and decorative designs. Today his work is considered folk art.

By the late 1840s, the daguerreotype was providing cheaper and faster portraits than any painter could. Field offered his services as a daguerreotypist in Massachusetts, and switched to painting historical subjects.

Historical Monument of the American Republic

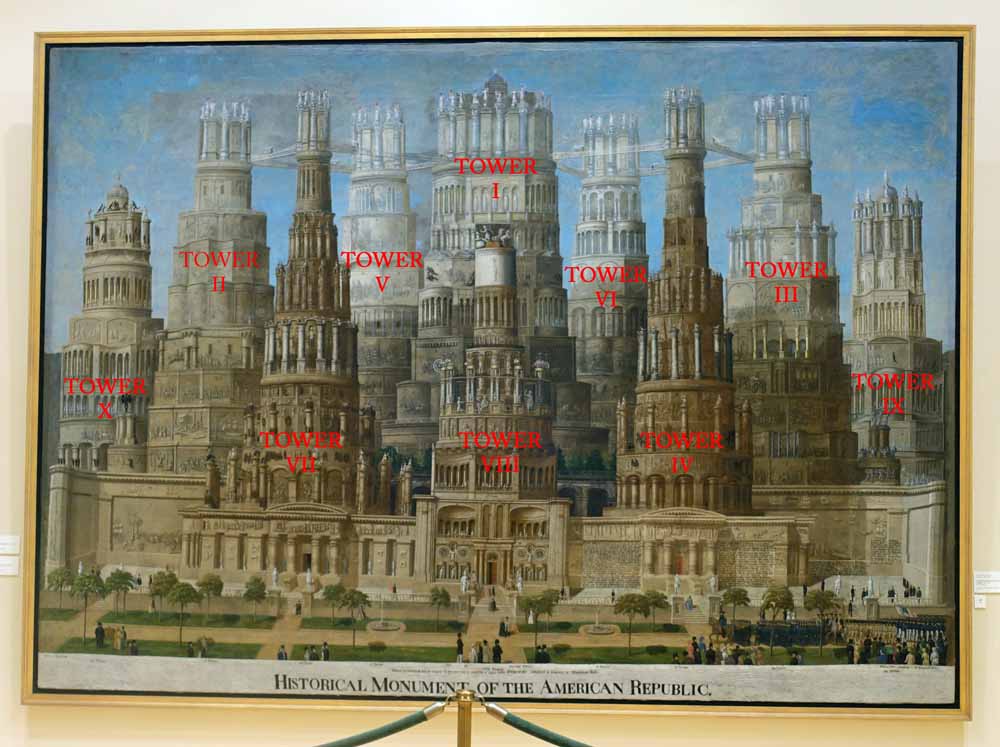

Field may have begun the Historical Monument in just after the Civil War or in 1874, when a competition was announced for the design of the central building for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The painting was mostly completed by 1876, with eight towers.

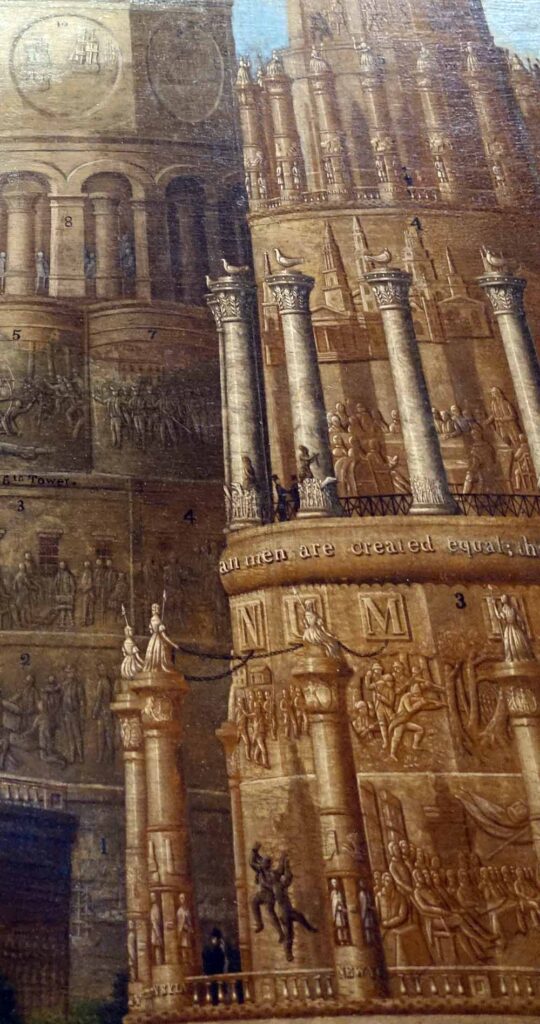

There is no particular order to the topics shown tower by tower, or to the scenes on each tower. Some scenes have inscriptions. Some don’t. To help viewers decipher the painting, Field published an eleven-page pamphlet explaining it scene by scene: Descriptive Catalogue of the Historical Monument of the American Republic (Amherst, MA, 1876). The pamphlet accompanied an engraving of the painting done in the same year.

Field planned to raise money by exhibiting the painting around the country, as artists such as Albert Bierstadt were doing (quite profitably) with large landscape canvases.

Judging from the Descriptive Catalogue, Field apparently hoped that his monumental towers would actually be constructed. The tallest would have been some 500 feet tall. (The Washington Monument is 555 feet, but of course not nearly so wide or so elaborately decorated.) In Field’s painting, the towers are set in a park in which elegant ladies and gentlemen stroll. A few mount the stairs at center front to enter the towers. “A professed architect, on looking at this picture, might have the impression that a structure built in this form would not stand,” Field wrote. But he proposed to circumvent the structural problems by making the towers solid, except for a central circular staircase. Via the staircase, visitors could visit the latest American innovations on display on the upper stories.

In 1888, Field added the ninth and tenth towers, at the far left and far right. No explanation of the scenes on these towers has ever been found.

Field died in 1900, his towers never having been built. In 1933, the Historical Monument was found rolled up in an attic. It’s now hailed as a grand example of American folk art, and hangs in a place of honor at the Michele & Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield.

Only one copy of Descriptive Catalogue of the Historical Monument of the American Republic seems to exist in American libraries, and alas, no one has uploaded a copy of it to the Net. I’ve compiled the highlights of the towers from the sources listed at the end of this post.

Towers VIII and I

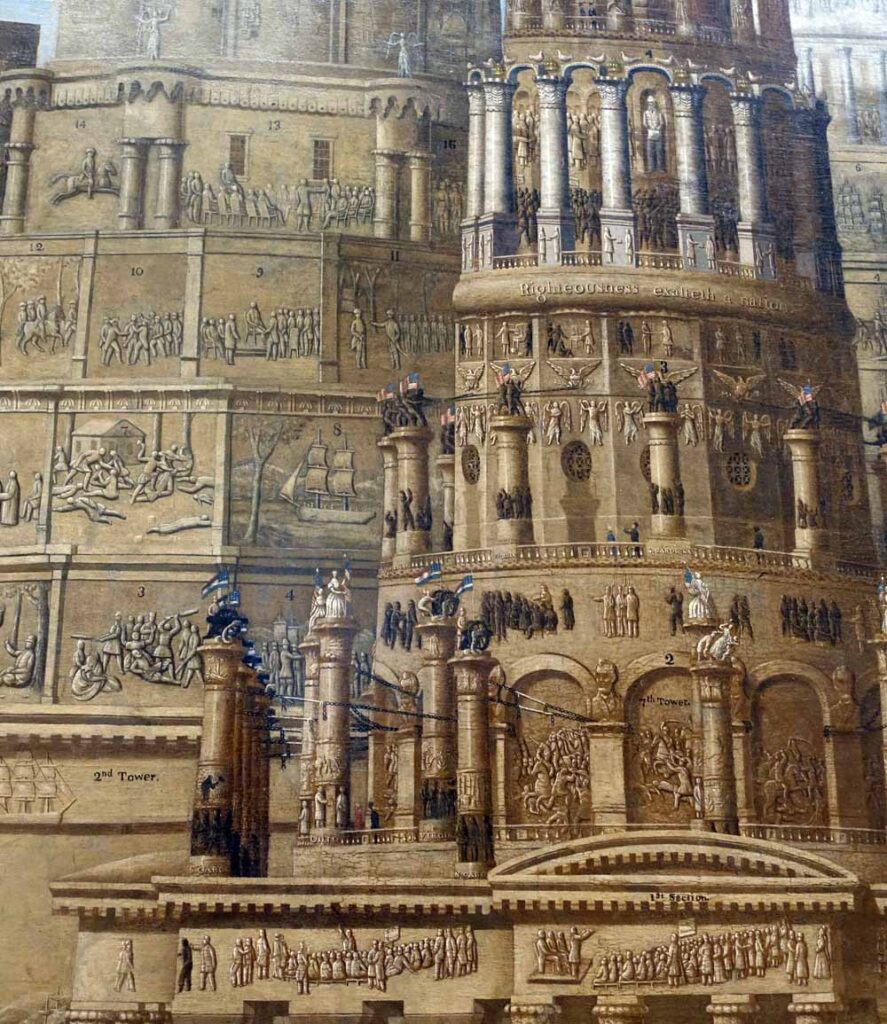

The lower of two towers at the center of the painting, Tower VIII, focuses on Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. At the top of Tower VIII, Lincoln rides to heaven on a fiery chariot. Midway up the tower Lincoln is assassinated by Booth, as George Washington watches, aghast, at the right.

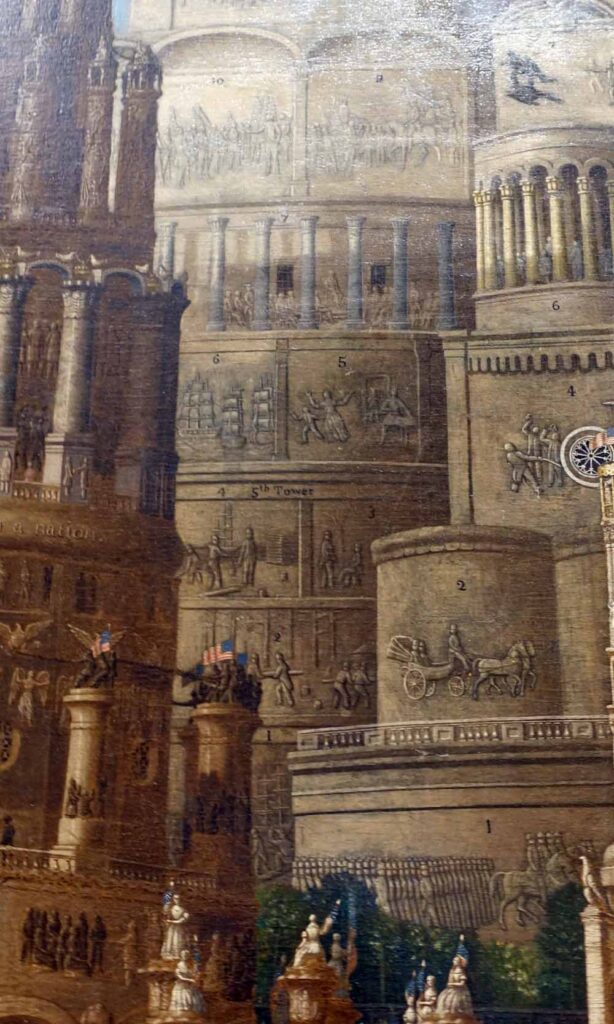

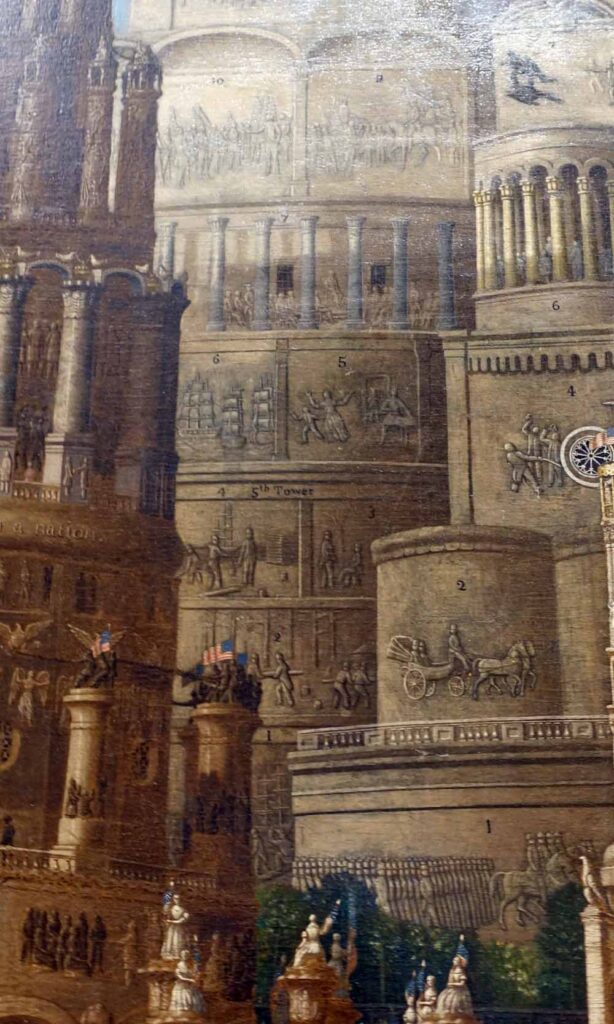

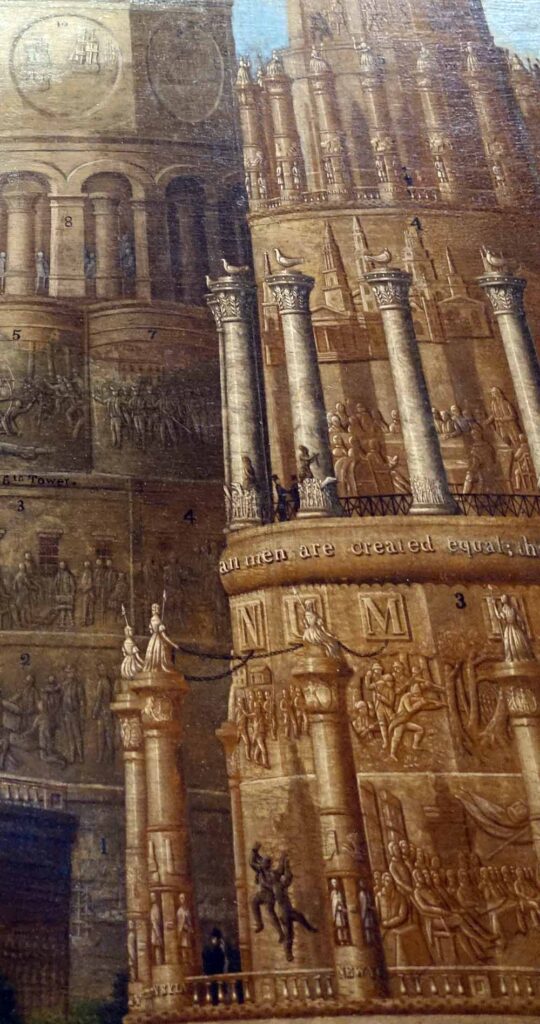

Tower I, the tallest tower, is behind Tower VIII. It shows events following Lincoln’s assassination. At the very top of this and six other tall towers, dancing women wave American flags, presumably celebrating the American Centennial in 1876. Six towers are connected by a series of iron-truss bridges, on which six steam locomotives can be seen chugging along.

Near the top of Tower I are the initials “T.T.B.” These also appear near the top of Towers II through VII. Field explained that these stood for “The True Base”. Field’s belief in the importance of religion for the country also comes out in the inscription related to the Bible at the base of Towers III and IV (on which, more below).

Towers II, VII, and V

These three towers are just left of the central towers (VIII and I). The focus here is on events that occurred in the South.

The large rectangular relief at the base of Tower II (the second tower from the left) shows the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. That one’s easy to spot. According to various sources, higher up on Tower II are scenes from the Jamestown Massacre (1622), Bacon’s Rebellion (1675-1676), the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the War of 1812, and the deaths of Adams and Jefferson in 1826. I have to admit, here and in many of the other towers, that I can’t tell which scene is which.

Rising from the base of Tower II (above the Jamestown relief) is a short tower topped by a jaunty figure of Satan. Below him is an inscription in Field’s somewhat shaky lettering: “The institution of Slavery we inherited from the good old patriarch, please let us alone all ye trouble of Israel.”

Tower VII, just right of Tower II, shows scenes preceding and during the Civil War.

Tower V, just right of Tower VII, includes (from the base up) early settlements in Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia; scenes from the French and Indian Wars; Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown; Robert Fulton’s steamboat; and Daniel Webster‘s famous 1830 speech (“Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”).

Towers III, IV, and VI

Towers III, IV, and VI show scenes from the North.

At the base of Towers IV and III is a lengthy inscription. Usually one has to put some effort into figuring out an artist’s metaphysical views. Field puts his views front, and nearly center. Excerpts:

The Bible is a brief recital of all that is past, and a certain prediction of all that is to come. It settles all matters of debate, resolves all doubts, and relieves the mind of its scruples. It reveals the only living and true God …The Bible is a book of laws, to point out right and wrong; a book of wisdom, which condemns all foolishness and vice; and a book of knowledge, which makes even the simple wise … It is the ignorant man’s school-master, and the wise man’s dictionary. It furnishes knowledge, witty inventions for the ingenious, and dark sayings for the grave; and it is its own interpreter …

Tower III, the second tower from the right side, starts at the base with the landing of the Pilgrims in 1610. It includes the Boston Massacre (1770), the Boston Tea Party (1773), Washington’s inauguration (1789), the Whiskey Rebellion (1794), and Samuel Morse inventing the telegraph. At the top of the tower are Washington and Ulysses S. Grant.

Tower IV, just left of Tower III, celebrates the freedom of the American people. It includes the Continental Congress (1774), the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Constitutional Convention (1787), and wars over Florida and Mexico. At the top of the tower is Bleeding Kansas (1854-1859).

Tower VI, just right of Towers I and VIII, and left of Tower IV, shows at the base the settlement of New York (1610) and William Penn’s treaty with the Indians (1682-1684). Above are the Stamp Act (1765) and the War of 1812. At the top, the Fugitive Slave Act is signed (1850).

Towers X and IX

Towers X and IX were added in 1888 to the far left and far right, respectively.

No key to them has ever been found. Tower X, at the left, is clearly related to the South (as are the other towers left of center), because on the bases of the columns near the top are abbreviations for Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina. But what else is going on, we have no idea.

Tower IX is at the far right. I am fascinated but perplexed by the second set of reliefs from the top (just below the columns), in which a Janus-faced man holding a pointer and a sheet of paper (?) looks at different groups of men in three separate scenes.

To read more about the Historical Monument of the American Republic, see the following sources.

Sources

Simpson, Kay. “Erastus Salisbury Field, 1805-1900).” Handout at the Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield (a.k.a. Michele & Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts).

Stait, Paul. “Erastus Salisbury Field, 1805-1900. Historical Monument of the American Republic, 1867-1888.” Originally published in Selections from the American Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts and the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, 1999; available online at http://tfaoi.com/aa/3aa/3aa157.htm.

“Erastus Salisbury Field Paints … And Paints … And Paints His Masterpiece.” New England Historical Society, unsigned, undated. https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/erastus-salisbury-field-paints-paints-paints-masterpiece/

Robinson, Frederick B. “The Eight Wonder of Erastus Field.” American Heritage, vol. 14, issue 3 (April 1963). https://www.americanheritage.com/eight-wonder-erastus-field

More

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon print and Kindle formats.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.