This ten-part series is based on a walking tour I offered some years ago. Click “NYC walking tour” in the tag cloud for others in the series. Look for videos on my YouTube channel.

Introduction

On this tour, we’ll see:

- The building with more sculptures than any other in New York City

- Portraits of two media moguls

- One of the best sculptures of Washington in the United States

- A representation of the spirit of nineteenth-century capitalism

- The sculpture that’s probably been reproduced more often than any other in the history of the world

- And two of my own favorite sculptures – anytime, anywhere.

When I give a tour or a lecture on sculpture, I have two goals. First, I want you to understand and appreciate (if not like) the sculptures we look at. Second, I want you to learn how to look at and appreciate any other sculptures you see. In other words, I want you to be able to look for yourself, not just nod at what I say that I see. Aside from that, there are two recurring themes in this particular tour: allegorical figures (what they are, how to interpret them) and the importance of setting.

1st stop: Surrogate’s Court, sculptures at ground level on Chambers Street

We’re looking at two figures on the south side of the Surrogate’s Court, which are visible at sidewalk level in this photo, on either side of the three arched entrances.

Here they are in close-up.

My usual approach to a sculpture is to look at the details, then identify the subject, and then work my way to the theme of the work – what the artist is saying is important and worth noticing. Only then do I consider the reasons for my emotional reaction and try to judge the work in esthetic or philosophical terms. (See this book for more on my method.)

Taking that approach with these two sculptures caused me many frustrating hours. Eventually I decided I couldn’t identify the figures because they’re not meant to be stand-alone sculptures. They’re allegorical figures attached to a building, and to understand their meaning, one must understand their context. So we’ll start with a few words on allegorical figures and on this building.

Allegorical figures

An allegorical figure is a human figure that represents not a real or fictional person, but an abstract idea or concept. Lawyers will be familiar with Justice, shown with a blindfold and holding the scales of justice and a sword. Other common examples are Liberty, Music, Fame, and Victory.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, allegorical figures featured prominently on many government buildings. The Municipal Building just across Centre Street is a nearby example.

Allegorical figures on government buildings tell us: “These ideas or these virtues are important for citizens of this city (or state, or nation).” Many allegorical figures are interesting and well executed. But they’re best appreciated if you approach them as an intellectual puzzle, rather than as stand-alone works meant to evoke an immediate personal reaction. You figure out what they represent first; the emotional reaction, if any, comes from that.

Surrogate’s Court

The Surrogate’s Court Building, completed in 1907, has more sculptures on it than any other structure in New York City. The fifth-floor cornice has eight life-size portrait sculptures. On the four facades are about thirty allegorical figures, including Chemistry, Electricity, Summer, WInter, History, Navigation, and Philosophy. This blog post lists all of them.

We’re going to look only at the two groups at ground level. Both are by Philip Martiny. Before we go any further, consider: do you like these? Note your gut reaction.

The Surrogate’s Court was originally the Hall of Records, a.k.a. the New York City archives. It was where the city’s historical documents were stored. Each of the two groups on the Chambers Street side, at street level, represents New York at a different historical period.

Allegorical figures on the right (east) side of the south facade

Let’s look first at the group on the right.

On one side of that group is an Indian, with a feathered head-dress, a loincloth, and a leather shield.

I don’t know if those details are ethnographically correct for any of the Native Americans who once inhabited Manhattan, but they certainly make the figure identifiable as an Indian. This figure suggests that this group is related to New York’s early history.

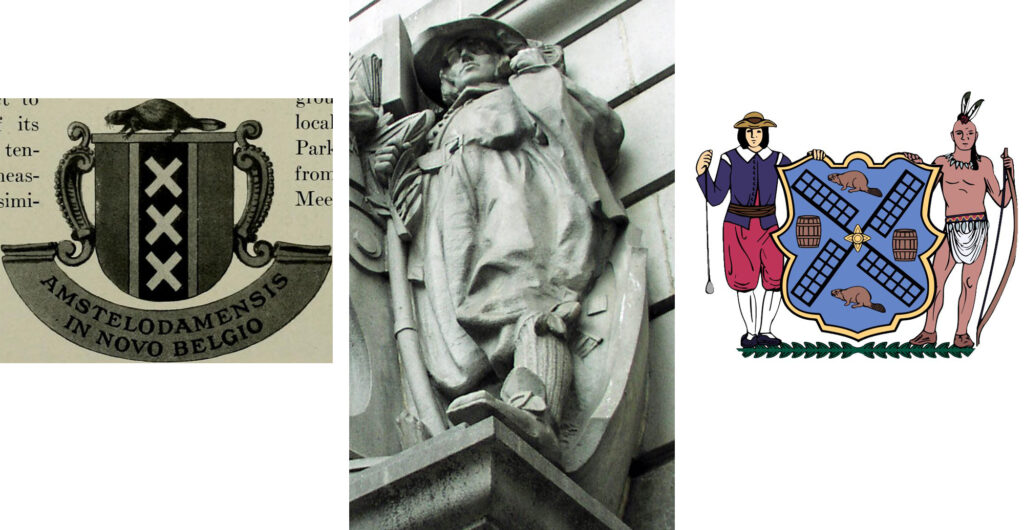

On the other side of this group is a man with a tall hat with a buckle and a feather, baggy trousers, and square-toed shoes.

Who in American history dressed like that? Either the seventeenth-century English (for example, the Puritans in Massachusetts) or the seventeenth-century Dutch.

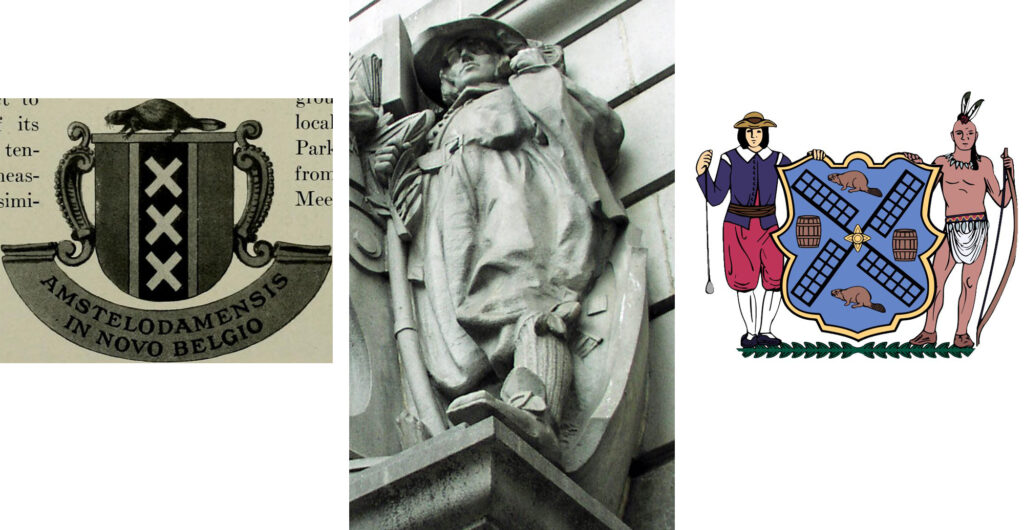

The Dutch founded New Amsterdam in lower Manhattan in 1624. The colony’s arms had three X’s down the center and a beaver on top. But the shield behind our figure doesn’t look like that: it shows a corner of a windmill, which appeared on arms of colonial New York. (They’re carved over one of the doors of the Surrogate’s Court.) So this figure must be English. The English took over New Amsterdam and renamed it New York in 1664.

The central figure of this group, a woman, shows what Martiny (the sculptor) thought New York was like under English rule. She wears a low, round crown, a reminder that the colony was ruled by a monarch.

Above and behind the woman is a palm branch. That’s a standard symbol for victory. Given the context, it’s probably the English victory over the Indians and the Dutch.

The woman has books in one hand, a rolled paper in another. That implies that the people of the time were educated, not illiterate. The cover of one of the books has the title “Lex,” i.e., “law”, and the paper has a seal that suggests it’s a legal document.

The message of this allegorical sculpture is that after the English took over New Amsterdam in 1664, the colony of New York was under the rule of a monarch, but also under the rule of law. Law and literacy suggest a fairly high level of civilization.

Allegorical figures on the left (west) side of the south facade

What’s the profession of the figure on the left of this group? He’s a soldier: he wears a uniform and helmet, and holds a rifle.

He’s standing in front of a shield with the motto “Honi soit qui mal y pense,” the motto of England. So this soldier represents the might of the British Empire.

The woman on the right side wars a long dress in the style of the eighteenth century. She’s outdoors, wearing a hat and carrying a bunch of flowers. I’m pretty sure that’s a tool of some kind in her other hand. Behind her head are laurel leaves, which symbolize victory.

The shield peeking out behind her skirt bears stars and stripes. She represents Americans who, although they were mostly farmers, emerged from the Revolutionary War triumphant against the might of the British Empire.

The woman at the center of this group represents Martiny’s idea of what was important about New York City at the time of the Revolutionary War. She wars a helmet: she’s willing to fight.

In one hand is a torch. A torch often represents enlightenment, as in the Statue of Liberty.

Her other hand supports a globe.

This seems odd because at the time of the Revolutionary War, the United States was certainly not a global super-power. But this sculpture was completed in 1907, less than a decade after the Spanish-American War, fought in Cuba and the Philippines. The globe in this figure’s hand foreshadows America’s international power by the early twentieth century.

Between the woman’s hand and the globe is an owl.

The owl combined with the helmet and the classical drapery make this woman identifiable not only as New York, but as Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom, war, and justice. By making the central allegorical figure of New York share Athena’s attributes, Martiny associates New York and her citizens with those qualities.

These two groups portray New York as it was before and after the Revolutionary War: in colonial times, with a literate population and rule of law, and after independence, with justice, wisdom, and the ability to defend herself.

I asked at the beginning of the tour if you liked these at first glance. How do you feel about them now? Do you like them more or less? In allegorical figures, as with most works of visual art, knowledge makes a difference. Allegorical figures can be superb technically, but an emotional reaction usually comes only after you understand their content and context.

Next week: the highly controversial allegorical sculpture that used to stand in front of City Hall.

More

- Since 2019, I’ve been posting New York’s outdoor sculptures in chronological order on my Instagram feed. My current series of blog posts are on outdoor sculptures in New York City that I haven’t written about over the past twenty years.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.