A video of this post is here.

The exhibition of Leonardo’s St. Jerome at the Metropolitan Museum (7/15/19 through 10/6/2019) will probably be mobbed … but you should go if you can. Leonardo made multiple major innovations in painting – innovations that gave himself and all the artists who followed him greater power to make viewers like us stop, look, and think about paintings. Seeing and understanding the work of anyone on that level is always worthwhile. If you live in the United States, this is one of your few chances to see a Leonardo: the only one of his paintings that resides here permanently is Ginevra de’Benci at the National Gallery.

Since the whole point of going to the exhibition is to look at the painting, I’ll talk about that first. Afterwards I’ll talk about who Jerome was, the historical context of the painting, and Leonardo’s innovations in this painting.

Warning: Take headphones or earplugs! The audio from a nearby exhibition in the Lehman Wing is loud enough to hear in the room where Leonardo’s St Jerome is displayed. If you’re there for more than a minute, the noise is quite annoying.

The painting

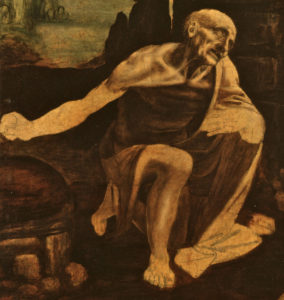

Leonardo began St. Jerome around 1480 and left it incomplete when he died in 1519. It was later sawed into pieces and then reassembled. Pieces are probably missing from the edges. Although we can’t judge this as a finished work, it reveals a great deal about what makes Leonardo’s work so fascinating and influential.

Here’s the painting as it exists today. This is not a bad photo – much of the painting is quite dark.

The area that immediately draws our eye is Jerome’s head and his right shoulder. Clearly these parts most interested Leonardo: he really worked on the detail here. The figure seems to be an emaciated old man. His face is wrinkled. His eyes, which strain upward, are sunk deep in his face. His cheekbones and jaw jut out. Only one tooth is visible in his mouth.

What about the rest of the figure? Although the shoulder is drawn with precise attention to bones and muscles, the rest of that arm and the hand are drawn only in outline. Yet their position tells us something about Jerome. He has a rock in his hand, and his hand is stretched away as far as possible. He’s going to beat his breast with that rock, and not gently, either: with as much force as his swinging arm can muster.

The loose drapery, barely sketched, is falling off. Beneath it we glimpse Jerome’s torso, where the ribs stick out like bare bones: another clue to how emaciated he is. His body twists and his leg is awkwardly bent into a kneeling posture. He looks wretched and humble.

No other human beings are present, but at Jerome’s feet, a lion is lightly sketched in. The lion is associated with Jerome because according to a later biography, Jerome realized that an angry lion who came to his monastery was being pained by a thorn in his foot. “Then this holy man put thereto diligent cure, and healed him, and he abode ever after as a tame beast with them.” (From Caxton’s translation of the Golden Legend; see below.) The lion looks up toward Leonardo. His mouth is open. Did Leonardo intend him to be roaring with anger at Jerome, or aghast? We’ll never know.

Jerome and the lion are in a dark cave. Behind Jerome at our left is the outside world – a mysterious rocky landscape, similar to that in his Virgin of the Rocks.

Jerome’s agitated gaze is focused at a break in the rocks to our right. The cross at which he gazes is within that bright area. It’s visible only as a few long vertical lines. In the distance within that same area, Leonardo sketched a church. Jerome is literally turning his back on the outside world in order to focus on God and the Church.

The direction of Jerome’s gaze is emphasized by the line of his arm: a strong diagonal from the hand through the arm, to the eyes, and then to the cross. Imagine if that arm hung at his side: our eyes wouldn’t move so surely upward and to the right. It’s the strong diagonal (the only one in the painting) that makes us look in that direction.

Let’s turn briefly from the “what” to the “how” of the painting: from the objects within it to their attributes. The amount of detail on Jerome’s face and shoulder is one reason we look immediately at them. Another reason is the highlights on Jerome’s bald head, cheekbones, jaw, and shoulder. The highlight on the front of his shin makes us notice that he’s humbly kneeling. Leonardo is famous for this technique: chiaroscuro, the contrast of bright light and darkness. In Virgin of the Rocks, which Leonardo worked on from 1495 to 1508, it makes the faces and gestures of the four figures stand out despite the darkness in the cave.

So: Leonardo’s painting shows an emaciated, humble, self-flagellating man who rejects the outer world (the landscape at left) to focus on religion (the crucifix, the church).

Jerome’s story

Jerome (ca. 347-420) ranks as one of the four Fathers of the Church due to his translation of the Bible into Latin (the “Vulgate”) and his extensive commentaries on the Old and New Testaments. Leonardo would have known of Jerome’s life from the Golden Legend, a collection of lives of the saints that was composed in the late thirteenth century. During the fifteenth century, it appeared in more editions than the Bible.

According to the Golden Legend, after becoming a cardinal at age 29 and studying with Gregory Nazianzen in Constantinople, Jerome retreated to the wilderness. There for four years he attempted to suppress his sexual desires by fasting and prayer. When he still had thoughts of earthly delights, he punished himself further. “I was oft fellow unto scorpions and wild beasts … and for to adaunt and subdue my proud flesh I rose at midnight all the week long, joining oft the night with the day, and I ceased not to beat my breast …” (Caxton’s translation of the Golden Legend.) In paintings that depict this part of Jerome’s life, he’s often shown staring at a crucifix while holding a stone with which to beat his breast.

Other paintings of Jerome

Because Jerome was one of the most important figures in the early Church, artists before Leonardo – and many after – tended to emphasize his dignity rather his suffering. Here are a few examples from the late fifteenth century.

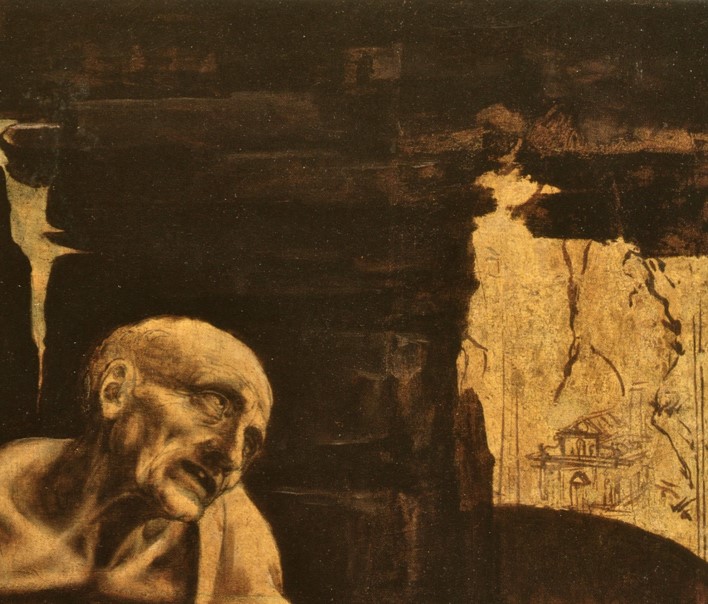

Ercole de’Roberti, St. Jerome, ca. 1470. Image: Wikipedia

Bernardino Pinturicchio, St. Jerome, ca. 1475-1480. Image: Wikipedia

And here are two from the early sixteenth century.

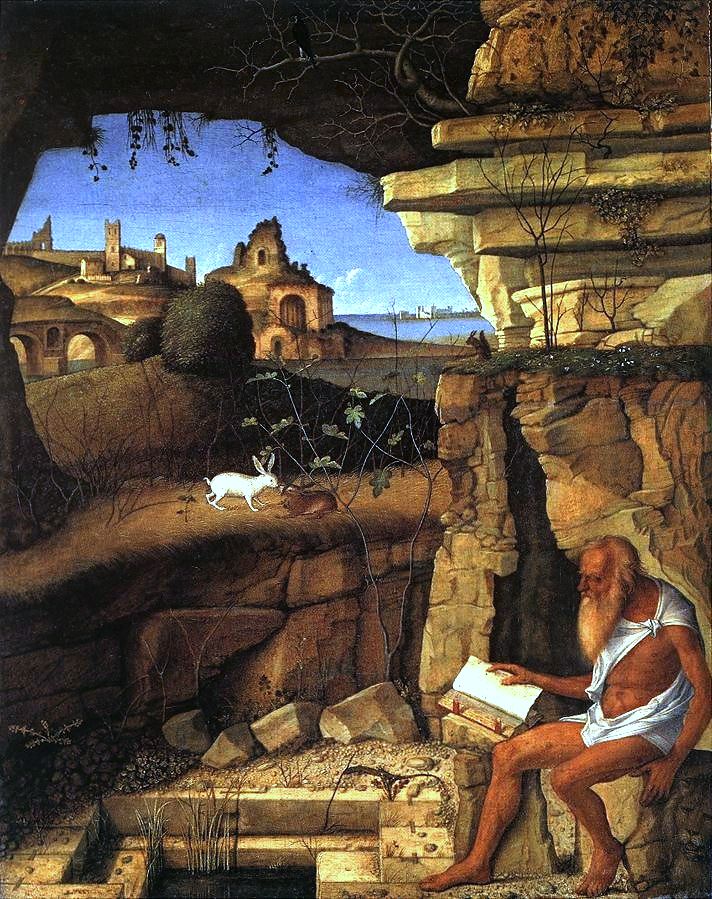

Giovanni Bellini, St. Jerome, 1505. Image: Wikipedia

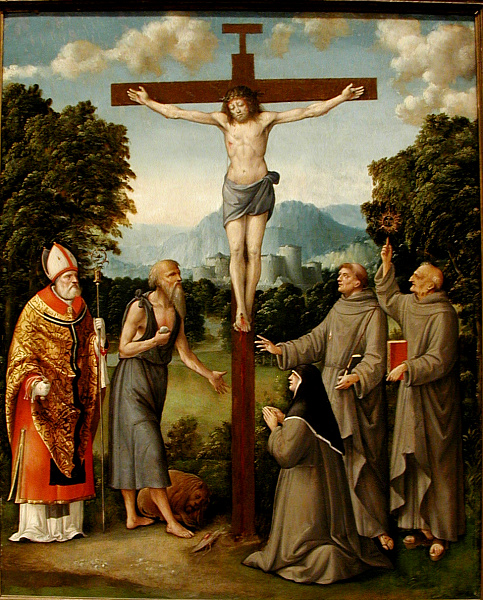

Martino Piazza, Crucifixion with Saints, 1515-1520. Image: MetMuseum.org

Unlike those artists, Leonardo didn’t say, “How would it be proper for a Father of the Church to look?” Leonardo is very much this-world oriented, even to the point of dissecting cadavers, a practice of which the Church strongly disapproved. Leonardo asked himself instead, “What would Jerome look like and feel like if he actually treated himself as brutally as he’s said to have done?” Leonardo’s answer: wrinkled, emaciated, bent, and almost toothless.

Leonardo as an innovator

What the Greeks and Romans knew about depicting man and this earth was lost after the Fall of Rome. During the Middle Ages, such subjects were not a priority. The important goal was to tell Biblical stories that would help save the souls of all those illiterate Christians.

Part of the frescoes from the Boscoreale Room, ca. 50-40 BC. Image: MetMuseum.org

Greco-Italian Madonna and Child, ca. 1250-1275. Image: Wikipedia

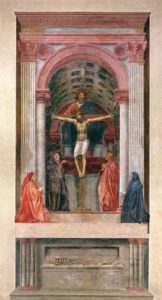

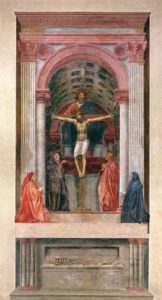

But beginning in the fourteenth century, European painters began relearning how to paint men and to create the illusion of three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface. In the early fifteenth century in Florence – the focal point of the Renaissance – Masaccio pioneered the use of mathematically calculated linear perspective in his Trinity and other works. Over the next few decades, Florentines painted charming, elegant, and dignified figures.

Meanwhile in Northern Europe, the use of oil paints allowed artists to render vivid colors, minute detail, and infinite gradations (useful for atmospheric perspective, among other things).

When Leonardo was born in 1452, his home town of Florence was the best place in Europe to learn about all the recent innovations in painting that had been discovered by Italian and Northern European artists. Leonardo proceeded to outdo all of his contemporaries in innovations. Only fifteen paintings are widely accepted as his work. Two of the largest and most complex are unfinished – this St. Jerome and his Adoration of the Magi. Yet of the two dozen or so major innovations in painting from cave paintings to the present, Leonardo was responsible for four. St. Jerome, begun in 1480, shows three of them.

One of the innovations is the sharp light/dark contrast known as chiaroscuro that throws a spotlight on certain parts of the painting. We saw that in the highlights that drew our eyes to Jerome’s head, shoulder, and bended knee. Using this, Leonardo had no need to emphasize important areas of the painting via distortions of size or garish colors.

Another of Leonardo’s innovations was the use of geometric forms in composition. In St. Jerome, the form is simply the diagonal line that runs from the rock in Jerome’s hand through his arm and his eyes to the crucifix. (In his Adoration of the Magi, 1481, the geometric forms are more complex.) With this sort of organization in his arsenal, Leonardo could include large groups of people or objects but still control where his viewers’ eyes focused.

A third innovation by Leonardo that’s illustrated in St. Jerome is the creation of portraits with riveting psychological depth. Italian painters of the early fifteenth century usually did portraits in profile, like portraits on Roman coins. Northern European artists produced exquisitely detailed portraits in three-quarter view (halfway between profile and full face). Artists from both areas created portraits that precisely rendered the physical characteristics of their sitters.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Woman at a Casement, ca. 1440. Image: MetMuseum.org

Memmling, Tommaso Portinari, ca. 1470-1480. MetMuseum.org

Memmling, Maria Portinari, ca. 1470-1480. MetMuseum.org

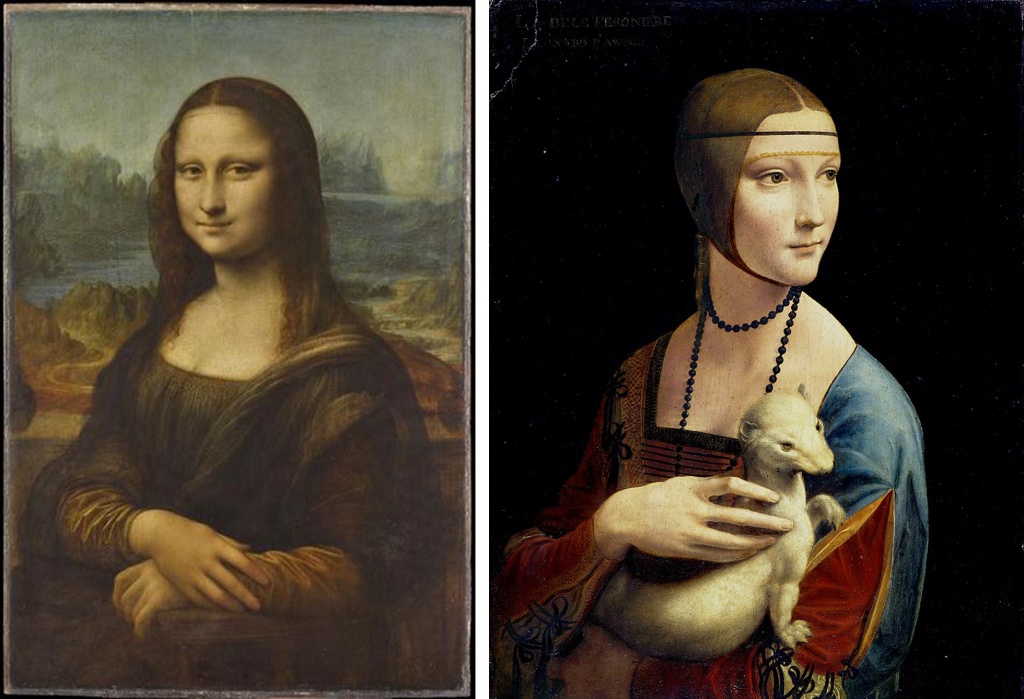

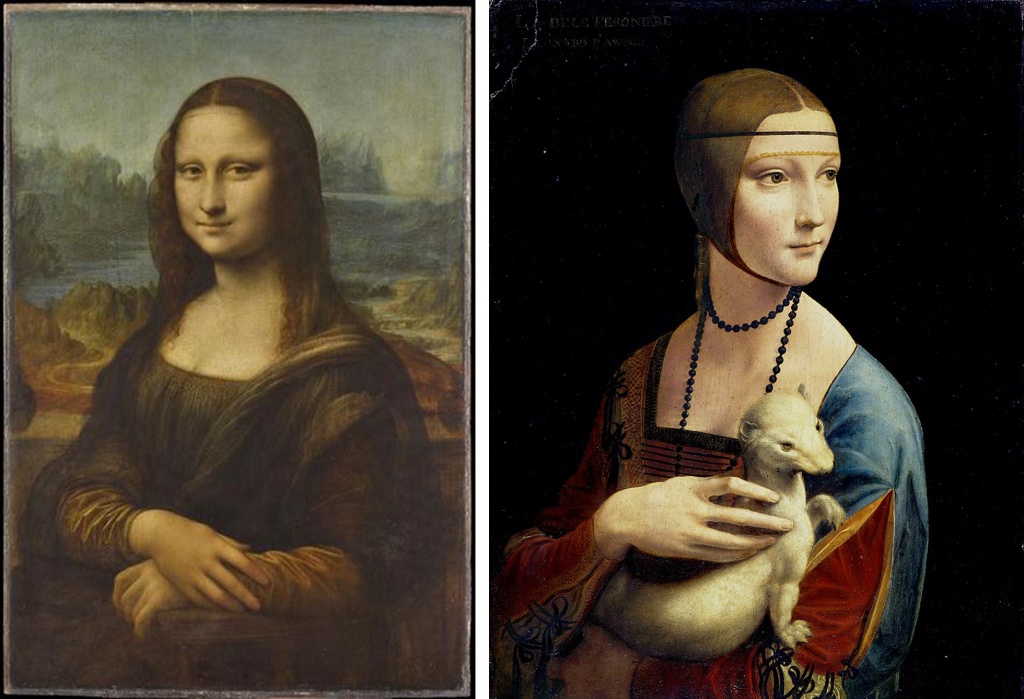

Leonardo’s innovation here was an obsession with showing not just the physical appearance of his sitters, but their inner lives – their characters. He conveys this partly by expression (which he renders with anatomical precision) and partly by the props and setting of his sitters. In finished paintings such as Woman with an Ermine (1473) and Mona Lisa (1503-1519), this psychological depth is obvious.

In St. Jerome, the character is conveyed by Jerome’s expression, his posture, his emaciated form, and his rejection of the outer world on the left for the religious symbols on the right. Whatever you think of Jerome’s desire to chastise himself by living in a cave in the wilderness, there’s no doubt that Jerome as depicted by Leonardo has achieved his goal. Jerome looks ghastly.

If you find Jerome difficult to look at … consider that Leonardo’s innovations gave artists such as Hals the ability to portray characters with emotional lives that you might find more appealing.

More

- In looking at St. Jerome for this essay, I’ve used the technique that I set out in How to Analyze and Appreciate Paintings: look at the image as a whole, identify the subject, look at the objects, look at their attributes, and finally look at the painting as a whole again.

- My book Innovators in Painting (with several chapters on Leonardo) is in progress. It focuses on innovations that gave the artists who created them- and all artists who followed – greater power to make viewers stop, look, and think about paintings. Innovators in Sculpture (2015) does the same for sculpture.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.