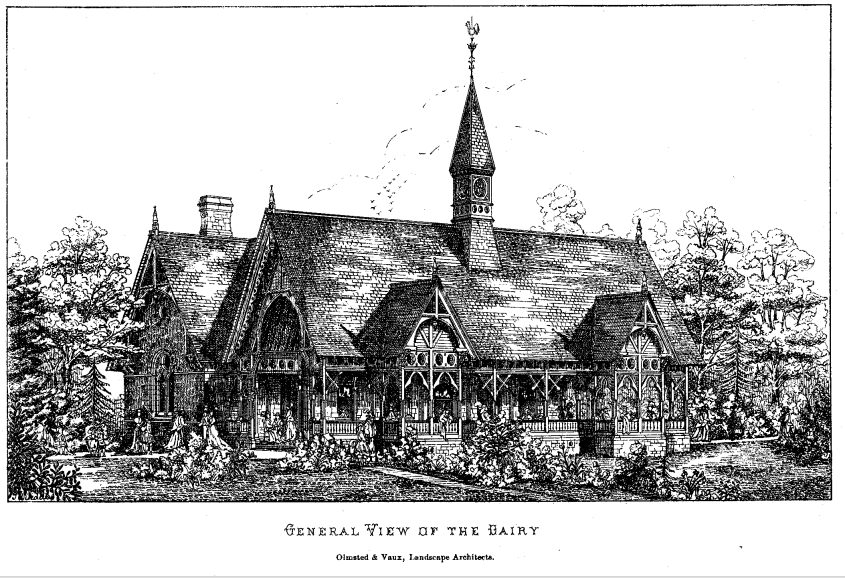

While researching Calvert Vaux, I suddenly wondered: Why was Vaux asked to design a building called “the Dairy” for Central Park? Yes, Olmsted and Vaux wanted a pastoral vibe, but having livestock on site (except for a flock of sheep) wasn’t in the plan.

I soon discovered that the Dairy was built in the aftermath of the “swill milk scandal” of the 1850s-1860s. Here’s the usual version of the swill-milk story.

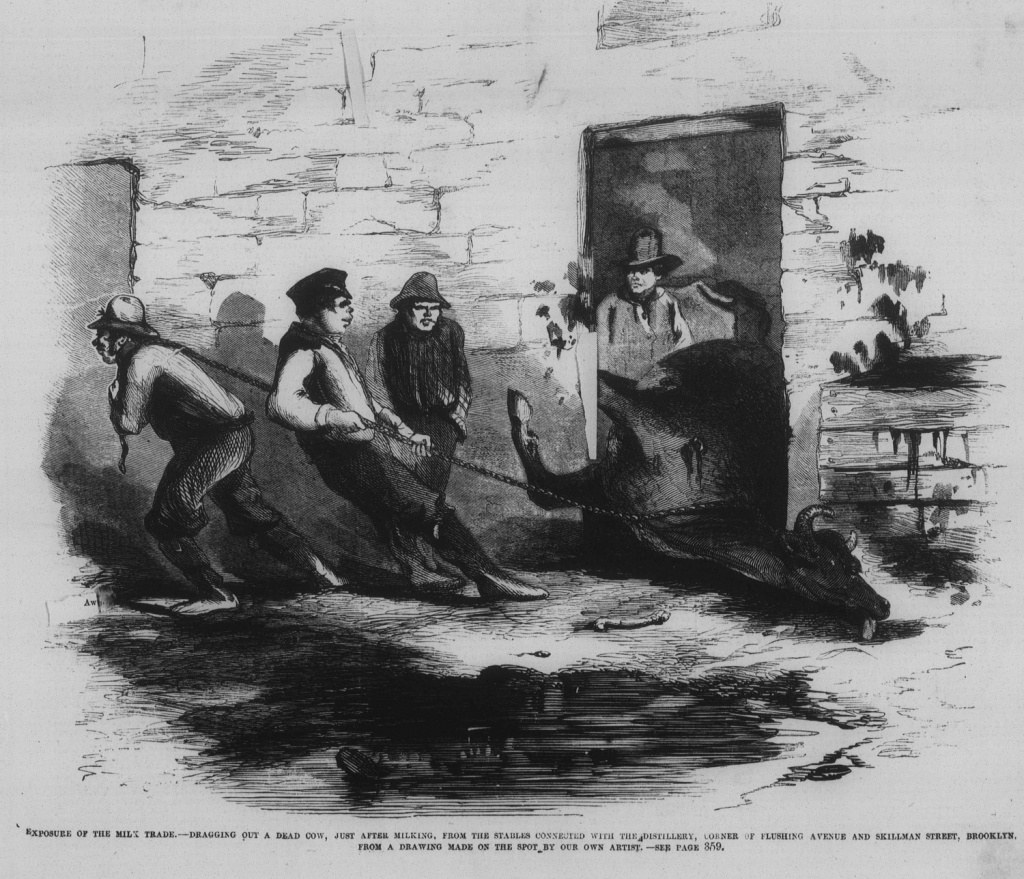

In the mid-19th century, owners of Manhattan distilleries started running dairy businesses on the side. They fed the cows what was left over of grain after it had been processed for alcohol. On this diet, the cows sickened, lost body parts (teeth, hooves, legs, tails), became too weak to stand, and died. In the meantime, they produced thin, bluish milk. To make this unappetizing product look better, the owners threw in an assortment of unsavory ingredients: flour, starch, plaster of Paris, etc. Every year some 8,000 children who drank such “swill milk” died. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper ripped the lid off the swill-milk story in summer 1858, with a series of front-page articles. In 1862, the New York State legislature made it illegal to sell swill milk or to adulterate milk. Problem solved.

Front-page story from the first Frank Leslie’s article on swill milk, 5/8/1858

That’s the usual story, but it left me with a couple nagging questions. As a farmer’s daughter and a sometime business owner, I couldn’t believe the owners of a whole agricultural sector would knowingly murder customers by selling a deadly product. As a mother, I knew that if the connection was obvious between feeding my child milk and watching him die, I would be a) raising hell with dairy owners and b) desperately seeking another other source of nutrition for my child.

So what explains the swill-milk story? I can’t get a sample to send for scientific analysis, and I can’t visit a distillery-dairy. So instead, I sat down to try to understand the context, based on what I know of the 19th-century from episodes of the Monuments of Manhattan (MoM) and Central Park videoguide apps. (More about those here.)

1. Why cows? Where cows?

Until the 20th century, canned food and pre-packaged baby formula didn’t exist. Milk from dairy cows was the main food for infants, once they were weaned.

From studying the early history of Central Park – why it was created and where it was located – I know that Manhattan’s population grew from 60,000 in 1800 to 500,000 in 1850. In 1800, you could probably keep a cow in your backyard or walk down the street to get milk from a neighbor’s farm. By 1850, Manhattan real estate was too much in demand to be used for grazing and stabling livestock. Dairy farms relocated to far-off places like Orange Country, West Chester County, and New Jersey.

But milk spoils easily, especially in the warm weather that New York experiences (when we’re lucky) for at least half the year. So how do you get the milk from those distant farms to Manhattan without spoilage?

2. Transportation

I know from reading up on Sherman (MoM #31) that in the early 19th century, any and all items that moved were transported on foot, by horses, or by ship. Ships – especially steamships, after 1807 – were faster than horses (Clinton and the Erie Canal, MoM #48), but ships weren’t large enough to make bulk transportation of liquids cheap.

Railroads came to New York in the 1840s, but from writing the essay on Alexander Lyman Holley (MoM #11), I know that early trains didn’t move very fast, because rails were of iron rather than steel. Iron rails couldn’t withstand the stress of speeding trains. The productive genius and competitive spirit of Cornelius Vanderbilt (MoM #25) made railroad transportation fast and cheap, but not until the 1860s. (Refrigerated train cars date to the1890s.)

Given the difficulty and expense of transporting milk from distant farms, I’m guessing that the creation of “distillery-dairies” was spurred by the fact that milk shipped in from the country was unaffordable for many families, and/or was often spoiled on arrival. (On 6/5/1858, Frank Leslie’s addressed the question “What are we to do when Swill Milk is abolished?” by blithely calculating the area within a 12-mile radius of Manhattan, and assuming it would provide plenty of area for dairy farms – without any consideration of whether the land was available for farming, suitable for grazing, or within reach of transportation.)

3. Germ Theory

From reading about Dr. J. Marion Sims (MoM #47), I know that well into the 19th century, even physicians didn’t know that diseases are caused by germs. That’s why (as I learned in researching the 7th Regiment Memorial for the Central Park app) amputations were so common the Civil War. It was safer to lop off a wounded limb and cauterize the stump than to hope that a wound wouldn’t lead to a deadly infection.

Ignorance of germs had a lot of repercussions.

a) Diseases without symptoms didn’t get diagnosed. When I was reading up on the swill-milk scandal for the Dairy episode, I learned that some cows had latent bovine tuberculosis, which could be passed to humans through milk. TB transmitted via milk must have caused many infant deaths. But at a period when physicians couldn’t diagnose and treat TB in humans, we can hardly blame farmers or distillery-dairy owners for not being able to diagnose and treat TB in cows.

b) Also because the germ theory of disease wasn’t known, many workers in the dairies – city and country – probably arrived at work filthy and/or sick, and unwittingly contaminated the milk or put it into filthy containers. The scientific reasons for requiring stringent sanitary procedures were not yet known. Again, we can’t blame the business owners for being in the same ignorant state as everyone else in the population.

c) From researching the Reservoirs, Viele, and Eagles with Prey (all for Central Park), I learned that waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid were commonly transmitted via the New York water supply. Never mind that the Croton Aqueduct had brought clean water from upstate since 1842. All that was required to contaminate that sparkling clear water was touching it with dirty hands or storing it in filthy containers. According to contemporary sources, milk was sometimes watered down by producers so they had more to sell. It was probably also watered down by consumers, to make it stretch further. Neither one was deliberately setting out to kill children, but if the water was contaminated, death could be the result.

4. Political corruption

Reading about the management of Central Park under Boss Tweed’s cronies and about the antics of Roscoe Conkling (OMOM #18), I was reminded that during the 1850s-1860s, corruption of government officials was widespread. Newly elected politicians handed out jobs to supporters, regardless of qualifications. Many of those supporters took the jobs with the intention of siphoning off as much public money as they could and extorting as much private money as possible.

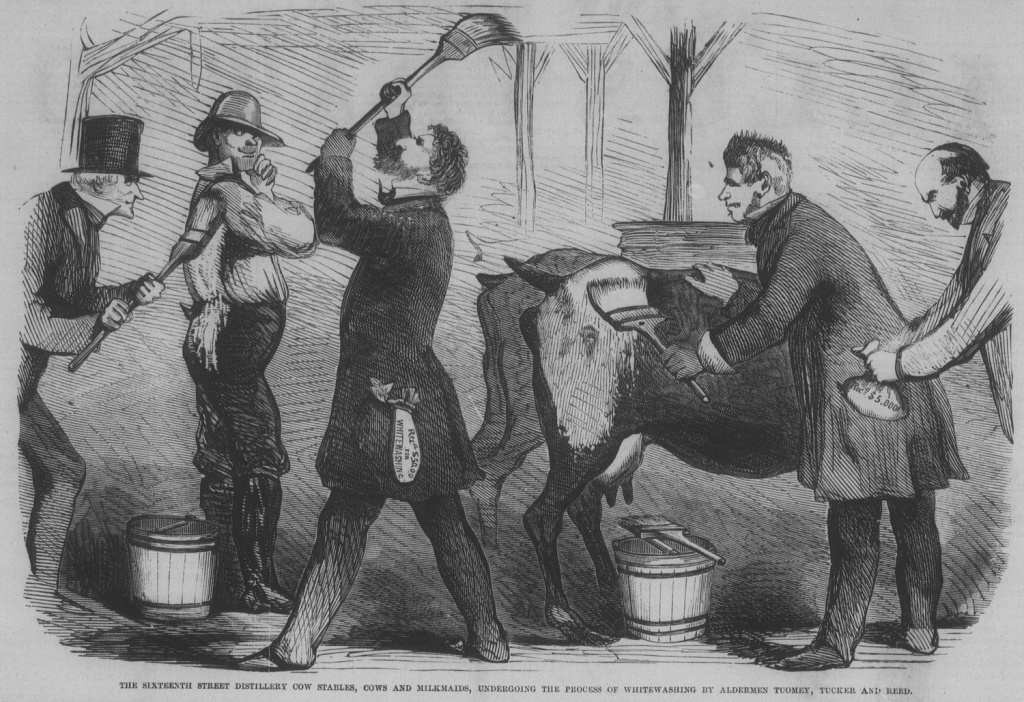

The milk-drinking masses, busy with their own lives, trusted the city’s Board of Health to shut down dangerous operations. According to Frank Leslie’s, the most egregious offenders among distillery-dairy owners simply paid the health inspectors to look the other way.

Where money is to be made, there are usually a couple vicious operators who get away with what they can, for as long as they can. Judging from the stories in Frank Leslie’s, some distillery-dairies were run under atrocious conditions: overcrowding of livestock, filthy conditions, sick cows, adulterated and contaminated milk. Whether vicious operators end up in jail or working another scam often depends on politicians. In the distillery-dairy business, corrupt politicians helped the worst operators stay in business. Frank Leslie’s reported in July 1858 (7/10/1858) that the Committee appointed by the Board of Health to investigate the distillery-dairies reported that all would be well if some minor improvements to ventilation were made.

From Frank Leslie’s (7/19/1858): Politicians whitewashing a distillery-dairy, its owner, and a decrepit cow. One of the politicians sued Leslie for libel.

5. Why the Dairy was built

The Dairy in Central Park was built in the late 1860s, a decade after the swill-milk scandal hit the front pages. For a nominal fee, parents who brought their kids to the Children’s District in the Park could buy milk that was guaranteed fresh.

Although the building retained the name “Dairy,” it was soon turned into a restaurant, and later a warehouse. Today it’s a visitors’ center.

6. A few words on raw milk today

Drinking raw milk has recently become fashionable. For the record, I drank raw milk from the cow down the lane until I was at least 10 years old. I don’t recall ever being sick from it. But living as I now do, far from that country lane, I wouldn’t drink raw milk if I didn’t know that it had been produced with the best of 21st century practice: the cow tested for communicable disease, the employee who milked it or managed the equipment trained in sanitary procedures, the vessels in which it was stored sterilized, the transportation by which it was conveyed to me refrigerated.

Drinking raw milk is no longer the risky business that it was in the 19th century. But speaking as a farmer’s daughter, it takes a lot of science and technology to go “natural” safely. Nature can be one mean mother.

7. References

- John Mullaly, The Milk Trade in New York, 1853.

- “Swill Milk: History of the agitation of the subject – The recent report of the Committee of the New-York Academy of Medicine,” New York Times 1/27/1860. An overview of reports on swill milk beginning in the 1840s. The rebuttal to this somewhat snarky review appeared in the New York Times on 2/1/1860, as “Swill Milk: A vindication of Dr. Percy’s report to the Academy of Medicine.”

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (via Accessible Archives, by subscription): lengthy articles in the issues of 5/8/1858, 5/15/1858, 5/22/1858, 5/29/1858, 6/5/1858, 6/12/1858, 6/19/1858, 6/26/1858, 7/10/1858, 7/17/1858, 7/24/1858, 7/31/1858, 8/7/1858. The articles include illustrations of several distillery-dairies, cows in various states of decay and disintegration, “milkmaids” (burly men) attacking reporters, corrupt politicians defending the dairy-owners at government meetings, and long lists of the routes of the milk-delivery wagons that set out from the distillery-dairies.

- The Guides Who Know app “Monuments of Manhattan” (preview here) is based on Dianne Durante’s Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide, New York University Press, 2007. The episode numbers above correspond to the essays in Outdoor Monuments, so if you don’t have an Android phone to run the app, try the book.

Addendum

I wondered if cows were intended to be kept in the basement of the Dairy, for exceedingly fresh milk. There were sheep in the Park; why not cows? On the north side of the Dairy, opening onto the 65th Street Transverse, there’s a door where cows (not very large ones, though!) might have entered the Dairy’s basement. But digging through the reports of the Board of Commissioners of Central Park and other contemporary sources, I found no evidence that cows ever took up residence.

Further reading

- On Governor Alfred E. Smith and milk regulation in New York, see here.

More

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.