Have you stopped to think about the way “My Shot” builds on the opening number of Hamilton: An American Musical? It sets him up as a young hero eager to change the world, but with a foreboding that drives him non-stop. Helluva number, and one of my favorites, for reasons I’ll explain in a bit.

Have you stopped to think about the way “My Shot” builds on the opening number of Hamilton: An American Musical? It sets him up as a young hero eager to change the world, but with a foreboding that drives him non-stop. Helluva number, and one of my favorites, for reasons I’ll explain in a bit.

But first, some entertaining sarcasm from Hamilton himself. Shift yourself back to the time when a clever soundbite wouldn’t send you viral on the Interwebs. What gets you attention – citywide or colonywide – is well-written, persuasive prose. If it’s witty, too, even better.

Rebellion stirring in the colonies

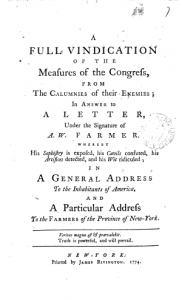

The Vindication was 17-year-old Hamilton’s first lengthy political tract, running to 35 pages in print. In eighteenth-century fashion, the title also functions as the table of contents and the dust-jacket blurb: “Vindication of the Measures of Congress, from the Calumnies of their Enemies; in answer to a letter, under the signature of A.W. Farmer. Whereby his sophistry is exposed, his cavils confuted, his artifices detected, and his wit ridiculed; in a general address to the inhabitants of America, and a particular address to the farmers of the Province of New-York. Veritas magna est & praevalebit. Truth is powerful, and will prevail.”

Before I conclude this part of my address, I will answer two very singular interrogatories proposed by the Farmer, “Can we think (says he) to threaten, and bully, and frighten the supreme government of the nation into a compliance with our demands? Can we expect to force submission to our peevish and petulant humours, by exciting clamours and riots in England?” No, gentle Sir. We neither desire, nor endeavour to threaten, bully, or frighten any persons into a compliance with our demands. We have no peevish and petulant humours to be submitted to. All we aim at, is to convince your high and mighty masters, the ministry, that we are not such asses as to let them ride us as they please. We are determined to shew them, that we know the value of freedom; nor shall their rapacity extort, that inestimable jewel from us, without a manly and virtuous struggle. But for your part, sweet Sir! tho’ we cannot much applaud your wisdom, yet we are compelled to admire your valour, which leads you to hope you may be able to swear, threaten, bully and frighten all America into a compliance with your sinister designs. When properly accoutered and armed with your formidable hiccory cudgel, what may not the ministry expect from such a champion? alas! for the poor committee gentlemen, how I tremble when I reflect on the many wounds and scars they must receive from your tremendous arm! Alas! for their supporters and abettors; a very large part indeed of the continent; but what of that? they must all be soundly drubbed with that confounded hiccory cudgel; for surely you would not undertake to drub one of them, without knowing yourself able to treat all their friends and adherents in the same manner; since ’tis plain you would bring them all upon your back. (Full text is at Founders Online.)

Also from the Vindication, here’s Hamilton’s passionate appeal to his fellow New Yorkers to fight for what they value, to “take their shot” – at this point metaphorically, in the form of an embargo on goods to Britain. He’s speaking to farmers, who were worried that the export ban would destroy their livelihood.

Is it not better, I ask, to suffer a few present inconveniencies, than to put yourselves in the way of losing every thing that is precious. Your lives, your property, your religion are all at stake. I do my duty. I warn you of your danger. If you should still be so mad, as to bring destruction upon yourselves; if you should still neglect what you owe to God and man, you cannot plead ignorance in your excuse. Your consciences will reproach you for your folly, and your children’s children will curse you.

You are told, the schemes of our Congress will ruin you. You are told, they have not considered your interest; but have neglected, or betrayed you. It is endeavoured to make you look upon some of the wisest and best men in the America, as rogues and rebels. What will not wicked men attempt! They will scruple nothing, that may serve their purposes. In truth, my friends, it is very unlikely any of us shall suffer much; but let the worst happen, the farmers will be better off, than other people.

Incidentally, the Congress in question is the First Continental Congress, whose “rogues and rebels” included John Adams, Samuel Adams, John Jay, Patrick Henry, and George Washington.

This post is already getting long, but do go to Founders Online and read the second paragraph – the one starting with “And first, let me ask these restless spirits, whence arises that violent antipathy they seem to entertain, not only to the natural rights of mankind; but to common sense and common modesty.” I used this paragraph in my walking tour of Hamilton sculptures years back (more on that here). Read aloud and with passion, it’s magnificent.

Hamilton’s death wish?

I would like to express how profoundly dissatisfied I am that no New York library has the Royal Danish American Gazette from 1776, and that no institution which owns it has digitized it. I want to read in full the letter Chernow quotes (p. 72):

It is uncertain whether it may ever be in my power to send you another line…. I am going into the army and perhaps ere long may be destined to seal with my blood the sentiments defended by my pen. Be it so, if heaven decree it. I was born to die and my reason and conscience tell me it is impossible to die in a better or more important cause.” (Cited by Chernow, p. 742, footnote 35, as “Extract of a Letter from a Gentleman in New York, dated February 18th,” published 3/20/1776.)

Newton, in the recent Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, questions whether Hamilton wrote this anonymously published letter. Still, I’d like to read the whole thing.

Rise up and pull down

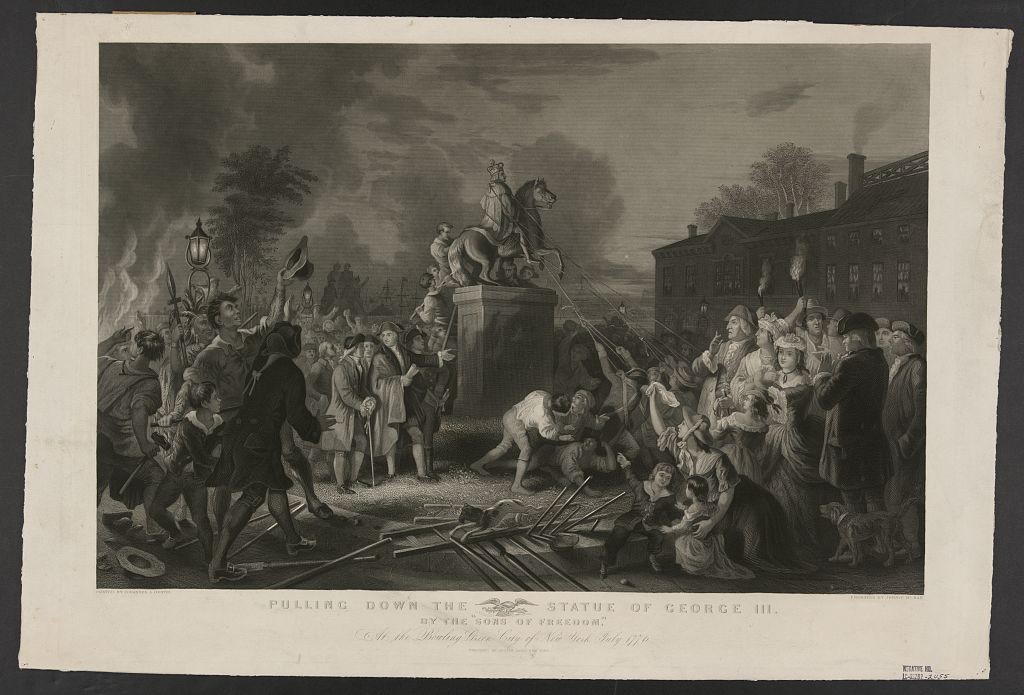

By the time the Schuyler Sisters appear in Hamilton: An American Musical, the Declaration of Independence has already been published. This post seems a good place to mention that when the Declaration was read in New York in July 1776, a mob led by the Sons of Liberty rushed from the Commons (City Hall) down to Bowling Green, where they yanked down a statue of King George III made of gilded lead. The lead was hauled off to Connecticut to be cast into bullets.

Three-quarters of a century later, the event was painted (rather … imaginatively) by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel. This article has fascinating details on the painting and the popular engraving done from it. Don’t miss the list of George’s surviving bits and pieces, including his horse’s tail and several others chunks at the the New-York Historical Society, which also has Oertel’s oil and a 20th-century sketched reconstruction of the what the King George sculpture actually looked like. For the modern reconstruction (3D!) see this post.

Artistic inspiration and artistic interpretation

Jumping ahead more than two centuries: the Hamilton soundtrack’s liner notes acknowledge elements of three songs in “My Shot”: “Shook Ones Part 2” (lyrics here), “Going Back to Cali,” and “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught.”

It seems to me that most of us listen to our parents’ favorite songs until we’re old enough to own a music player, and that we stop listening to new music after we hit our forties – which is coincidentally when our kids start finding their own music. My parents, whose favorite singers included Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, thought the Beatles were long-haired hippie freaks whose music would never last. Me and rap …. Well.

With that as an introduction, perhaps you’ll understand why the third song, from Rogers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific, is the only one of those songs that I’d want to hear again. But it was fascinating to see what Miranda did with the first two – like hearing a favorite performer do a riff on a piece I didn’t think I particularly liked.

My reasons for loving Hamilton: An American Musical

I was hooked on Hamilton: The Musical from the moment I heard “My Shot.” It has become my go-to song when I need to gather up my nerve and commit to a choice.

Untold numbers of people have weighed in with what they love about Hamilton: An American Musical, but none of them have named what sent the album to the top of my own playlist when so many other candidates are jostling for the position. Since I enjoy peeling my psyche like an onion, here’s what I’ve come up with. This is, of course, very much my own take. If you don’t agree, make a snorting noise and go read someone else’s blog.

1.The music is rhythmic, fast-paced, and often lyrical, which means I can hold it in my head and sing it. When music meanders so does my mind, usually in a diametrically opposed direction.

2. Lyrics. When I was 10 and there wasn’t much music competing for space in my brain, a cute pop lyric with a catchy tune would stick in my mind. (“Hey, hey, we’re the Monkees!” ?!?) But I grew up to be a polyglot polysyllabic philologist. I love the texture and precision of words. Common ones used in unusual ways. Uncommon ones that I seldom have the chance to use in conversation. Old-fashioned literary devices such as alliteration and assonance and consonance (“revolutionary manumission abolitionists”!). I’m amused by word play such as making “monarchy” almost rhyme with “anarchy”. Combine unusual vocabulary with rhymes that come so fast they almost trip over themselves, and I’m hooked. I can see the rap influence in the rhythm and rhymes and energy of Hamilton, but a great gulf separates the lyrics of “My Shot” from most hip-hop, rap, or mainstream pop lyrics.

3. Once is not enough. The words “my shot” are the start of a sequence. They’re referred to in the Lee duel, at Yorktown, in Philip’s duel, and in the Hamilton/Burr duel. The music reinforces the connections made by the words. The same happens with other key words and phrases, such as “satisfied,” “just you wait,” “rise up,” and “history has its eyes on you.” I love that, because it means that on the second (fourth, fifty-third) listening, I see layers of meaning that I didn’t grasp at first, as the lyrics twist, intertwine, and echo.

4. The positive sense of life. I am scarily susceptible to having my mood altered by music. Put me on hold with heavy metal and I turn into one mean mother. The mood throughout Hamilton is upbeat. Hamilton has strong opinions on what’s good and right. He uses all his considerable mental and physical energy to fight for it, and quite often, he achieves it. Such is the force of his personality that when he dies, Eliza and others remember his achievements and pick up the torch. If you think that’s a minor point: imagine the difference if the curtain dropped as soon as Burr fired his shot.

Take away any one of these four elements and I’d still like the soundtrack, but I wouldn’t be addicted. I still haven’t seen the show live, so I can’t say more than that, can I?

More

- For more on “sense of life,” see my essay “Vitamins, Minerals, and Harry Potter” or, even better, the discussion of “sense of life” by Ayn Rand, who coined the term.

- The book Hamilton: The Revolution, by Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeremy McCarter, will be published next month (4/12/16). It promises to trace the musical’s “development from an improbable performance at the White House to its landmark opening night on Broadway six years later. In addition, Miranda has written more than 200 funny, revealing footnotes for his award-winning libretto, the full text of which is published here.” Can’t wait!

- I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the eighth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.