- Sculptor: Daniel Chester French.

- Dedicated: 1907.

- Medium and size: Marble (ranging from 9.5 to 11 feet), each pedestal about 9 feet.

- Location: In front of the United States Customs House, facing Bowling Green between State and Whitehall Streets.

NOTE: This post is adapted from a chapter in Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. For other excerpts, click “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan book” in the tag cloud at right.

About the sculptures

An important part of learning to enjoy art is learning to focus on it for a substantial amount of time, and to figure out the effect of the details. Let’s practice on the Continents—one of the most complex ensembles in Manhattan.

A thought to bear in mind: what if the artist is attempting not to show not the inhabitants of a particular location, but something much broader?

Asia

At the far left of the Customs House facade sits Asia, eyes closed. Is she sleeping? No, because her back is erect and her chin up. Yet she’s willfully not looking at the world around her.

Her clothing seems almost too heavy to allow movement, and conceals the lines of her body. Her left hand rests on her lap, unmoving, next to a small statue of the Buddha. Held loosely within her right hand, almost like a scepter, is a poppy flower, source of narcotic drugs that deaden the mind. Up its stem slithers a snake.

While snakes have positive associations in some cultures, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition that predominates in the United States, snakes are the embodiment of evil. All is not well with this sedate figure, as becomes obvious when we look at what’s around her.

Asia’s footstool is supported by human skulls.

On the left is a tiger, strong, wild, and bloodthirsty. Significantly, he seems to be looking to the woman for orders, rather than wondering which part of her to eat first—his teeth and claws are not bared.

To our right of Asia are three men: almost naked, emaciated, hunched over, eyes closed. One has his hands tied behind his back: clearly he’s not a willing follower. Another is rolled into a ball with his face on the ground, in abject submission.

Behind Asia’s left shoulder is a radiant cross. Does she know it’s there? Is it meant as a symbol of hope, or to generalize the negative statement of the statue from Eastern religions to all religions? French leaves this ambiguous: he includes the cross, but doesn’t give it a prominent size or position.

Asia includes details that represent the refusal to look at reality, misery, tyranny, oppression, bloodthirstiness, drugged stupor, and evil. Could that be an accidental juxtaposition? Only if you believe French had a magic modeling tool that carved without his control. In fact, every detail in the Asia group had to be consciously selected by the sculptor. Because French presented these elements in this combination, we can assume that he believes there’s a relationship between religion (at least some kinds of religion), force, and human suffering.

Africa

At the far right side of the Customs House is Africa. Her partial nudity suggests heat so oppressive that action is unthinkable. Although she’s not emaciated like the men beside Asia, she’s sprawled in an exhausted sleep, too tired even to lie down. Her arm rests on a lion—a powerful beast, but also sound asleep.

To either side of her are reproductions of Ancient Egyptian monuments. On our right is a solar disk, the symbol of the god Horus; on our left is a sphinx, symbol of the pharaohs. Their decrepit appearance isn’t due to New York pollution. French carved them to look as if they are crumbling and decaying.

Behind Africa, to our left, sits a woman swathed in heavy robes. She’s not asleep—she’s upright, and holding her cloak across her face with one hand—but like Asia, she has closed her eyes and withdrawn from the world.

What does the Africa group say? Both the woman and the lion have great potential, but both sleep exhausted amidst the decay of once-great monuments. This figure did great deeds in the distant past, but has no energy to do anything now—not even to enjoy the memory of past greatness.

Europe

Europe, by contrast, sits proudly relaxed, looking outward. One hand is positioned as if to help her rise. She’s dressed regally, with a battlemented crown (it looks like a medieval fortress) and a breastplate reminiscent of the Greek goddess Athena’s aegis. The ropes of pearls twined into her hair indicate great wealth.

“Embroidered” around the hem of her gown are the arms of European royal families.

The items surrounding Europe recall her impressive history. The reliefs on her throne are copies of those on the Parthenon. At her shoulder sits the imperial Roman eagle. Behind her, on our left, are the prows of Viking ships: a reminder that Europeans had been exploring the world and trading for centuries.

Moving around to the right, we see that the woman’s arm rests on a huge book, which symbolizes the transmission of knowledge. (Neither Asia nor Africa has any books.) The book rests on a huge globe—the world that Europeans explored and then dominated for centuries.

Behind Europe a cloaked figure, aged and gaunt, hunches over a book and a laurel-wreathed skull. Laurels often represent victory and fame, but here the wreath encircles the skull of a man long dead. The combination suggests that Europe tends to dwell on past glory.

The difference between Europe’s and Africa’s ancient glories is that Europe is still aware enough to recall her discoveries, learning and trade. She’s rightfully proud of her accomplishments, even though she is now serenely sedate.

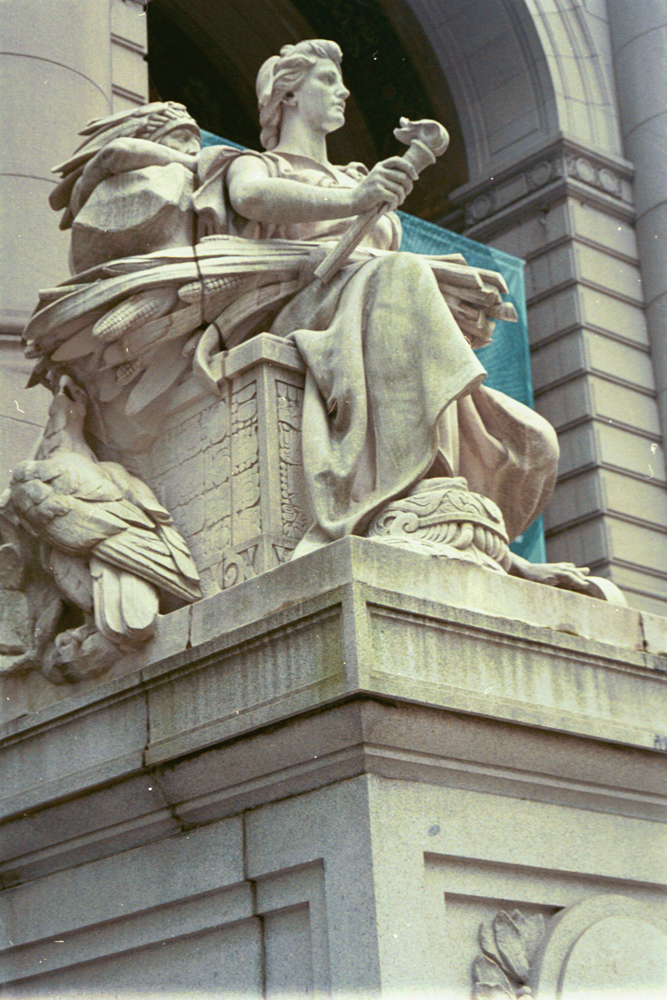

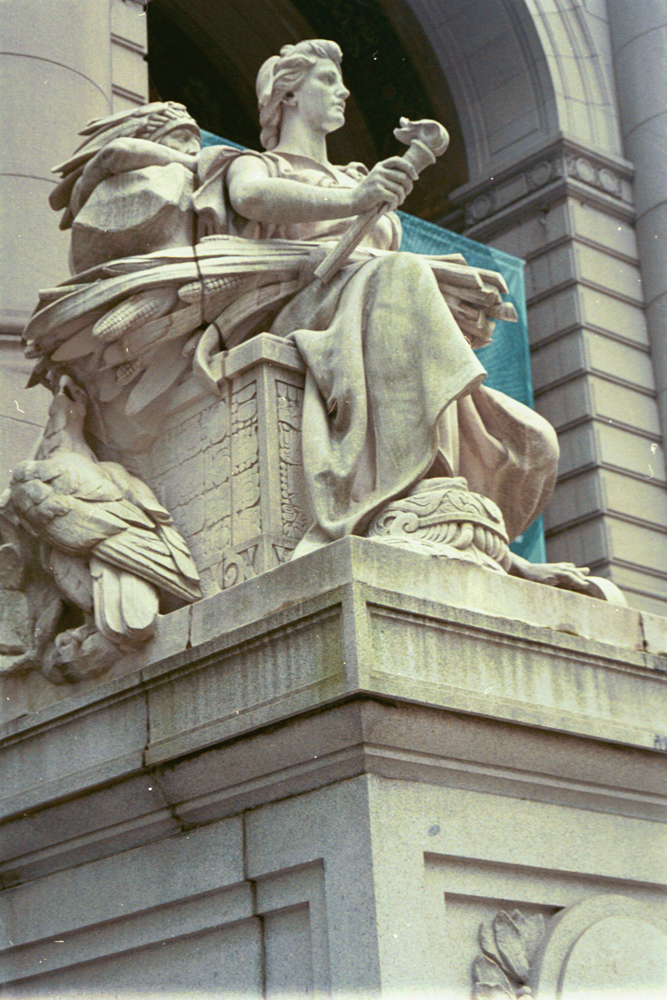

America

Finally there’s America. What’s different about her? She’s actually moving, with one leg shifted back to take her weight as she rises. The flowing dress outlines her torso, emphasizing her twisting movement. Her hair is looser and more natural than that of either Asia or Europe.

In America’s lap are stalks of corn, symbol of agricultural produce.

The nopal cactus on our left, a distinctively American plant, produces prickly pears and serves as food for the cochineal insect, which in turn produces an expensive red dye. America, French tells us, is a country that creates goods as much as monuments.

America’s right hand holds a torch, a symbol of enlightenment (as in the Statue of Liberty and the Verrazzano). Her left arm protectively encircles the man at her side, and she draws her cape forward to shelter him.

This man is a startling contrast to those who accompany Asia. He’s strong, healthy, energetic, alert. The chisel in his left hand and the paper in his lap imply that he has a plan for action.

With his other hand he pushes a “wheel of progress.” The symbolism of this is a bit obscure (although the same object appears on the spandrels above the windows in the Grand Central concourse), but it’s clear this man is going somewhere: wheels are for motion. Of all the figures accompanying the Continents, this man is the only one who’s healthy, alert, and cooperating with the main figure.

America is surrounded by Native American motifs. Her footstool is an ancient Aztec carving. Her throne bears Mayan glyphs. Behind her is the top of a totem pole from the Pacific Northwest, and below it, ceramic pots that look vaguely Southwestern.

Judging from his feathered headdress, the watchful figure peering over America’s right shoulder is a Plains Indian.

Why did French incorporate so many Native American motifs? Perhaps to emphasize how different America’s history is from that of Europe, Asia or Africa.

The Continents as a group

Consider the Continents not as representatives of the people who live on each continent, but as illustrations of states of mind and their results. Asia represents the type of person who focuses on an unseen, supernatural world; with this come misery, bloodshed and countless human deaths. America is alert, productive, and energetic, able to put natural resources to practical use; the humans and animals around her are peaceful and healthy. Europe is intelligent and proud, but living in her glorious past. Africa is exhausted amid the ruins of long-decayed greatness. The fact that French placed Asia and Africa at the outer edges of the building, and America and Europe at the center, flanking the building’s main entrance, makes it clear which states of mind French considers more important and admirable.

You’ll notice even more about these sculptures by comparing them with each other. For example, Europe and Africa both have reminders of the past, and both have a cloaked figure seated behind—but what differences in the details, and in the message!

French, Africa (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

French, Europe (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Asia and America both have nearly naked figures to one side, animals on the other side, and footstools: the similarity of these basic items makes the differences between them even more noticeable.

French, America (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

French, Asia (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Europe and America both have eagles on the left, but one is the heraldic Roman eagle, stiffly posed, while the other is so tame it nibbles on America’s sheaf of corn.

French, America (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

French, Europe (one of Four Continents), 1907. Customs House. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Cornice Sculptures

In keeping with the building’s trade-related function (see About the Subject), the sculptures along the Customs House cornice commemorate nations engaged in international trade through the ages.

From left to center, here they are.

Frank Edwin Elwell, Greece and Rome . Cornice of the Customs House, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

About the subject

Why is the Customs House so huge and elaborate? Money, money, money. Until the Sixteenth Amendment instituted the income tax in 1913, most federal revenue came from customs duties collected at American ports. About 75% of foreign commerce passed through the Port of New York. In 1905, while the Customs House was under construction, the federal budget was about $500 million. It collected $183 million of that through customs duties at New York.

No wonder, then, that one of the country’s outstanding architects, Cass Gilbert, was chosen to design the new home for New York’s Customs officials. No wonder Gilbert was allotted $4.5 million for the project, including funds for a lavish decorative program. As the New York Times chirpily put it in 1906:

When all the world comes to the Port of New York to be taxed, although they may grumble at some of Uncle Sam’s tariffs, they will at least enjoy the privilege of paying tribute in a building fronting on Bowling Green whose palatial dimensions and architectural adornments have not been equaled or attempted in any other Custom House in the world. Whether this privilege will act as a palliative to the foreign pilgrim when he comes in practical contact with the complications of our tariff is not altogether certain.

More

- In 1905 and 1906, the New York Times published articles on the models of French’s Continents. See here for excerpts.

- Daniel Chester French on creating art:

[French] was especially happy in his work. He never agonized over it and it was seldom drudgery to him. Each statue as it came along was an exciting challenge, each difficulty met with in the mechanics of his trade was an absorbing problem to be overcome.

Daniel looked forward to doing the Custom House groups with more enthusiasm than he had felt for anything in a long while. Then he realized that he really felt almost the same enthusiasm in practically everything he did. Each new commission was a separate experiment, a widely differing challenge.

Margaret French Cresson, The Life of Daniel Chester French: Journey into Fame, 1947

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and recurring support: details here.