This blog post is available as a video. The illustrations below are the slides from the video. NOTE: Not all of the works in this post are in the the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition on Delacroix, because some are too large and/or fragile to travel. For a list of works in the exhibition, see this page.

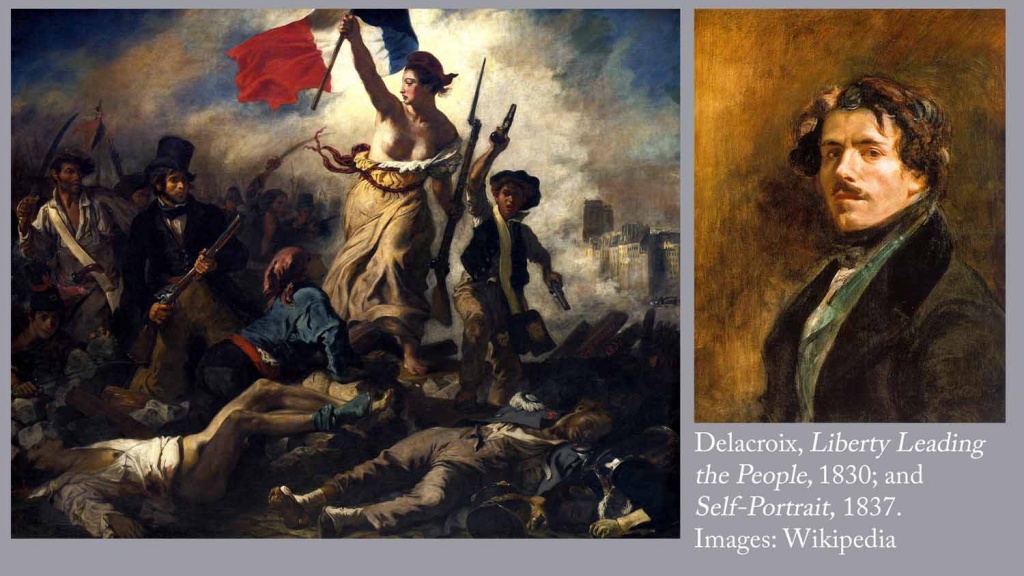

The Metropolitan Museum is running a major exhibition of Eugene Delacroix’s works through January 6, 2019. I will say up front that I’m not Delacroix’s biggest fan. With the possible exception of the self-portrait shown here, I wouldn’t want any of his paintings hanging in my home. But Delacroix was enormously influential in the 19th century. If you’re interested in the progression of 19th-c. art, or you’re a fan of Monet, Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, or a host of other painters of the late 19th century, he’s someone you should be familiar with. He’s also interesting for his viewpoint on reason, emotions, and the creation of art, which I’ll get to at the end of this essay.

The Met’s exhibition includes over 150 works by Delacroix, but few if any by earlier French artists. I’m maniacal about knowing context, so my goal here is to help those who aren’t well-versed in art history to understand Delacroix, by showing how his works fit into the art milieu of the time.

The Source of This Essay

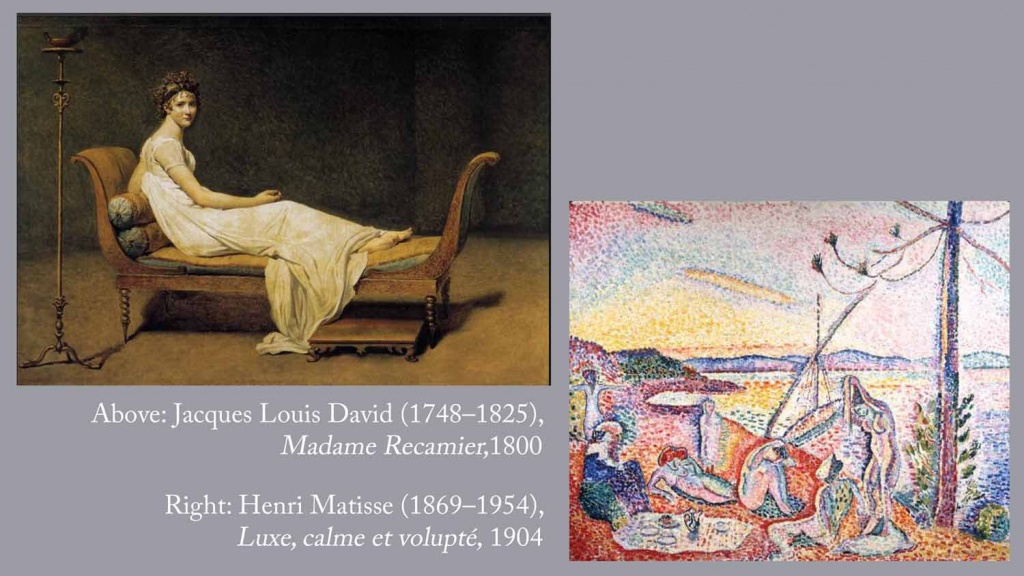

My discussion of Delacroix is part of a chronological survey called Seismic Shifts in Subject and Style: 19th-Century French Painting and Philosophy. The essay looks at how French artists switched from creating works such as Madame Recamier, by Jacques-Louis David (1800), to Luxe, Calme, et Volupte, by Matisse (1904).

Artistic trends are not the result of some collective consciousness working its will. They are simply the styles that the majority of individual artists in a given time choose to embrace. In Seismic Shifts, I seek the reasons for those changes via a combination of art analysis and philosophical detection … which happens to be the sort of problem that fascinates me. The essay covers eighteen French artists, from the Neoclassicists, Romantics, and Naturalists through Manet, the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Pointillists, Symbolists, and Academics.

In the philosophical-detection sections of the essay, I searched for the comments of those artists on four issues crucial for artists:

- The role of training for an artist: is it essential, optional, detrimental?

- What are the roles of reason and emotion in creating art?

- Is subject more important than style, or vice versa?

- Who is qualified to judge art?

Neoclassicism

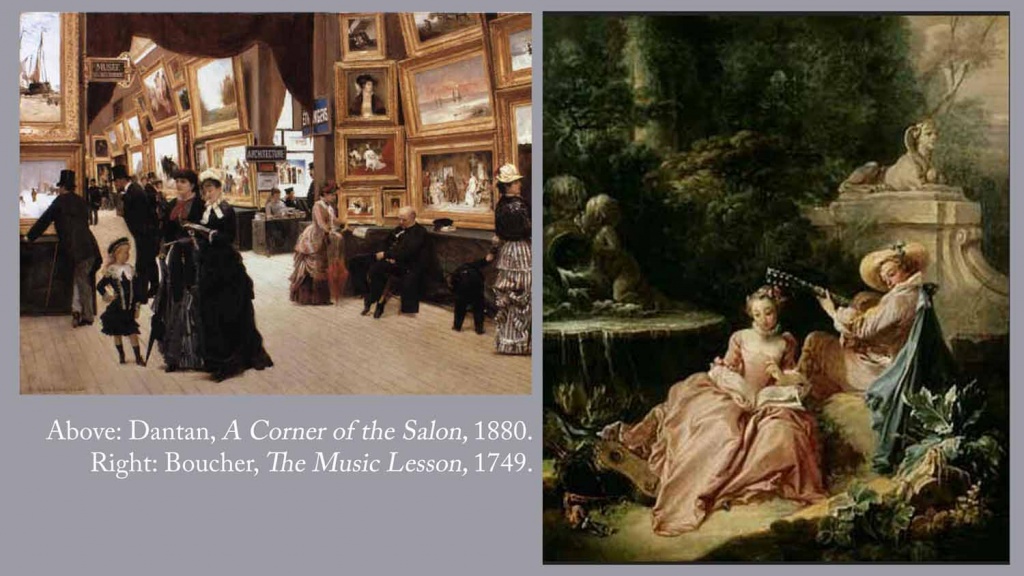

Because I’m focusing on Delacroix in this post, I’m skipping the sections of Seismic Shifts that discuss the French Academy, the French Salon, and the Rococo style.

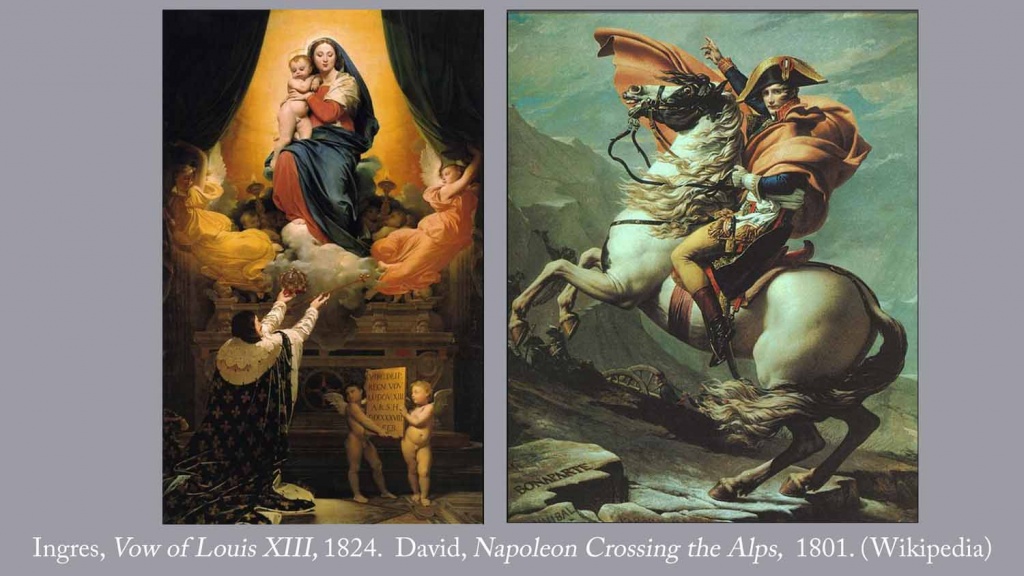

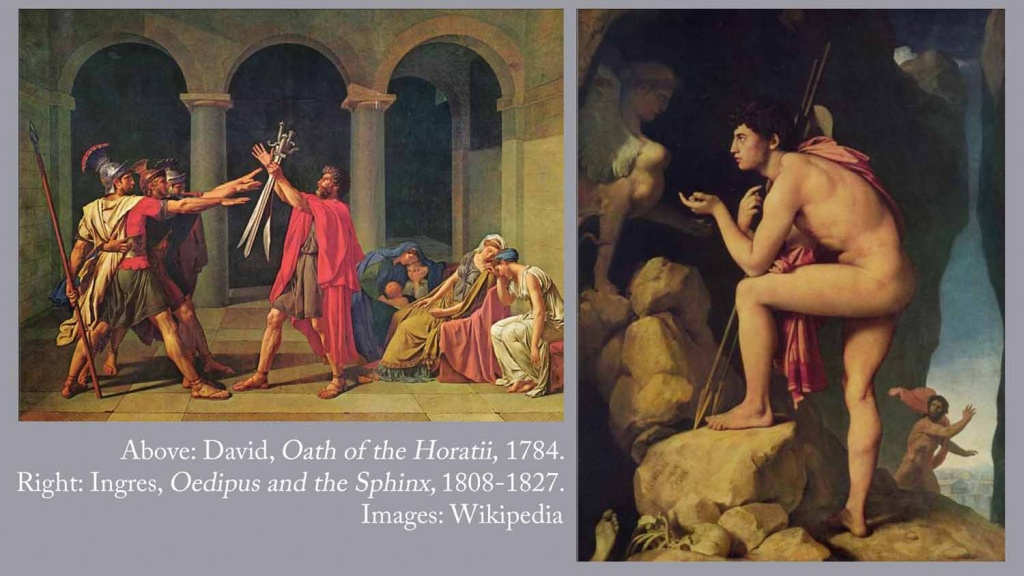

But we do need to look briefly at the Neoclassicists, the style that was dominant when Delacroix and other Romanticists came on the scene. The Neoclassicists were at their peak from the 1780s to the 1820s.

For centuries, artists had believed that the function of art was to educate men by showing the good and the beautiful. Neoclassical painters continued that tradition. The figures in their paintings were usually grand and heroic. They moved in a world where heroic and dramatic events are possible.

The Neoclassicists had a distinctive style for showing this world: precise lines, meticulous details, clear lighting, and balanced compositions.

Neoclassicists discuss art

How did the Neoclassicists respond to the four issues that we are following regarding art and philosophy? The most prominent figures, David and Ingres, seem to operate on the Enlightenment assumption that man can know reality through the senses and logical thought, and can act to improve himself and his world.

1. On the matter of training for artists: David and Ingres thought it was essential. They were both academically trained, and ran highly successful ateliers for aspiring artists.

2. What about the role of reason in the creation of art? David said, “The guide of genius is the torch of reason.” Ingres said good art is the product of hard work and education. On a broader scale, David and Ingres assumed reason was involved in art because they saw art’s purpose as didactic, and both teaching and learning involve disciplined mental effort.

3. What is the relationship between style and subject? David said that style is more important than subject, but he seems to have meant that it is acceptable to use well-known subjects, so long as one interprets them for oneself. Ingres apparently concurred when he said that artists did not need to seek out the new: “Our task is not to invent but to continue.”

4. Who should judge art? David thought the people should judge art, since artists themselves were not always competent to do so. Ingres said that taste is based on education and experience, which implies that esthetic judgement requires observation and rational thought.

Romanticism

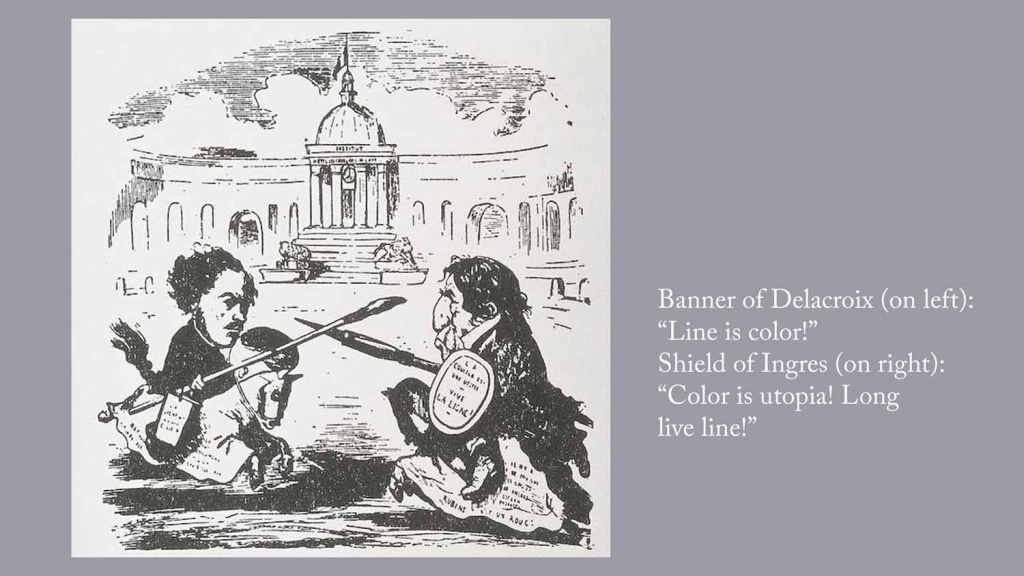

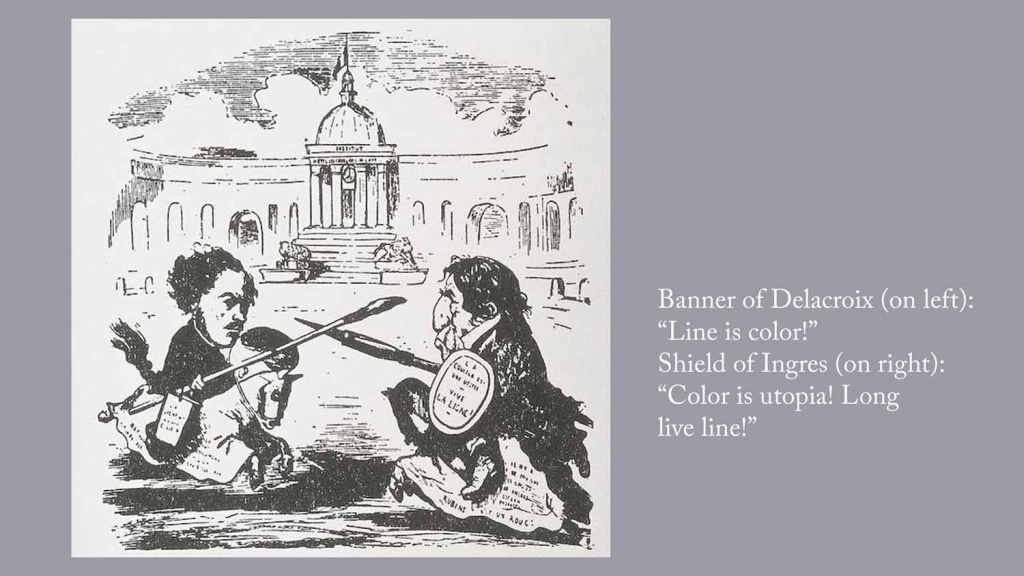

During the 1820s, Neoclassicism was replaced on the cutting edge of art by Romanticism. However, Neoclassicism and Romanticism continued to exist side by side for several decades. In 1855, Ingres and Delacroix each had a roomful of paintings on display at the Universal Exposition in Paris.

You might ask: what exactly is Romanticism? That’s a tricky question. Scholars agree that Romanticism’s origins reach back at least to Edmund Burke’s 1757 Inquiry into the Origins of the Sublime. But no artist at the time and no scholar since has been able to define what exactly “Romanticism” means. By the mid-1820s, about 150 different definitions had been suggested, none of which gained general acceptance. If you start considering modern definitions – Ayn Rand’s definition of “romanticism,” or the meaning behind a romantic dinner – the list gets far longer.

Perhaps the main reason for the early disagreements is that Romanticism’s premises and implications differed from one country to another, one decade to another, and particularly from one discipline to another.

In philosophy, German Romantics such as Fichte (1762-1814), Schelling (1775-1886), and Schopenhauer (1788-1860) advocated outright mysticism. “The whole body is nothing but objectified will, i.e., will become idea,” wrote Schopenhauer.

In literature, authors such as Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), Victor Hugo (1802-1885), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881), and Edmond Rostand (1868-1918) stressed the individual and his emotions.

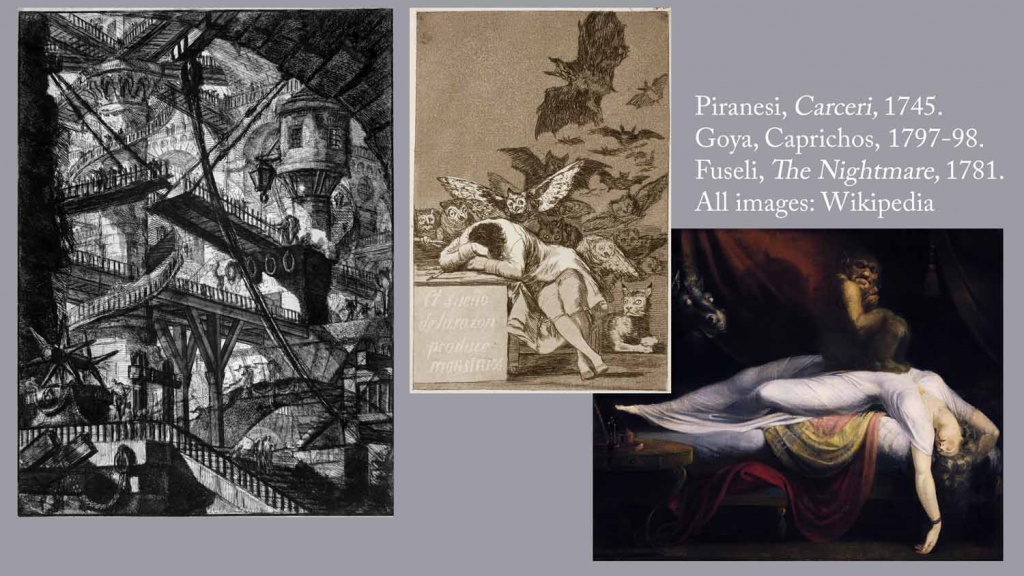

In the visual arts, Romanticism was largely confined to painting. Beginning with Giovanni Battista Piranesi Henry Fuseli, and Francisco de Goya, artists rebelled against the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” that Winckelmann had advocated, and which, in the form of Neoclassicism, had swept through Europe during the late 18th century. Romantic painters focused on subjects calculated to arouse strong passions. The passions could be as positive as love or as negative as terror. The important thing was to make the viewer feel something.

The first important French Romantic painter was Baron Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835). Gros’s Napoleon in the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804, a huge 18 x 23 feet, illustrates the Romantics’ striving to evoke emotions. General Bonaparte touches one of his soldiers suffering from bubonic plague. People of the time considered that action either magnificently brave or suicidal. Maybe both.

Theodore Gericault, the next important Romantic painter, favored anonymous modern figures in dramatic situations. His breakthrough painting was the twenty-three-foot wide Raft of the Medusa, 1819. Its depiction of a shipwreck that ended in death and cannibalism was calculated to rouse horror and pity in the viewers.

Eugene Delacroix

When Géricault died in 1824, at the age of 33, Delacroix (1798-1863) became the most prominent artist among the French Romantics. In 1827 he and Ingres each had significant works on display in at the Paris Salon.

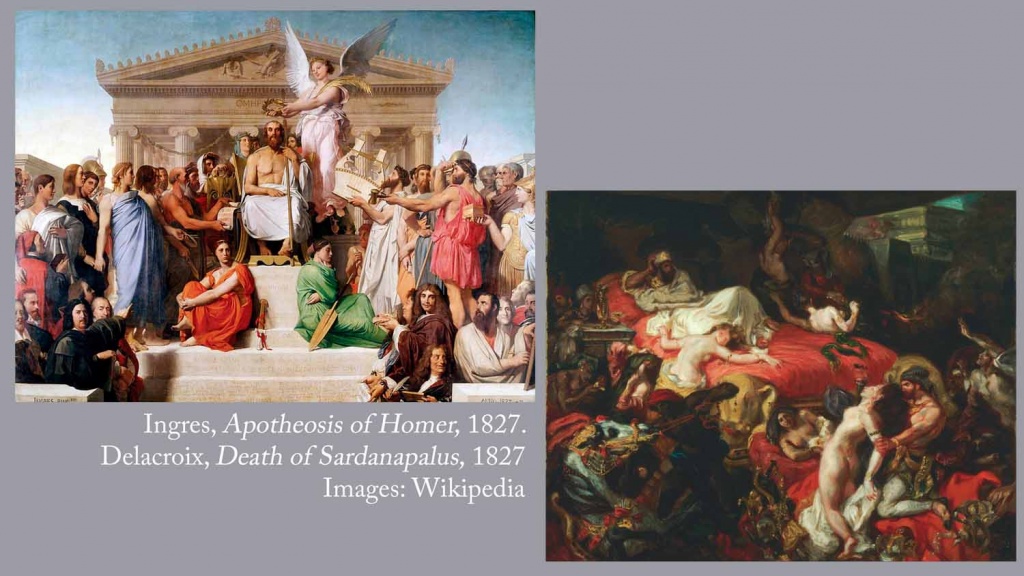

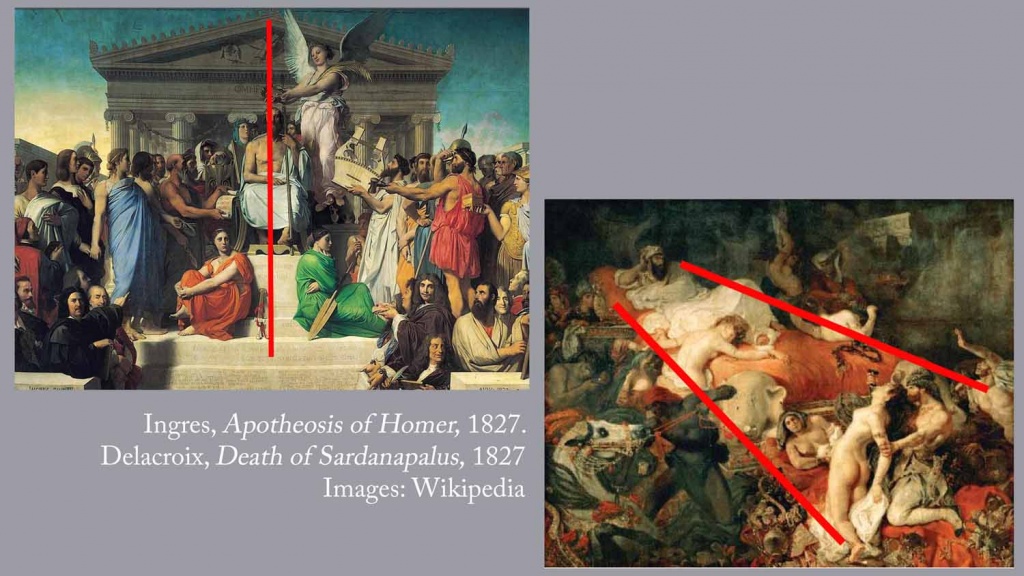

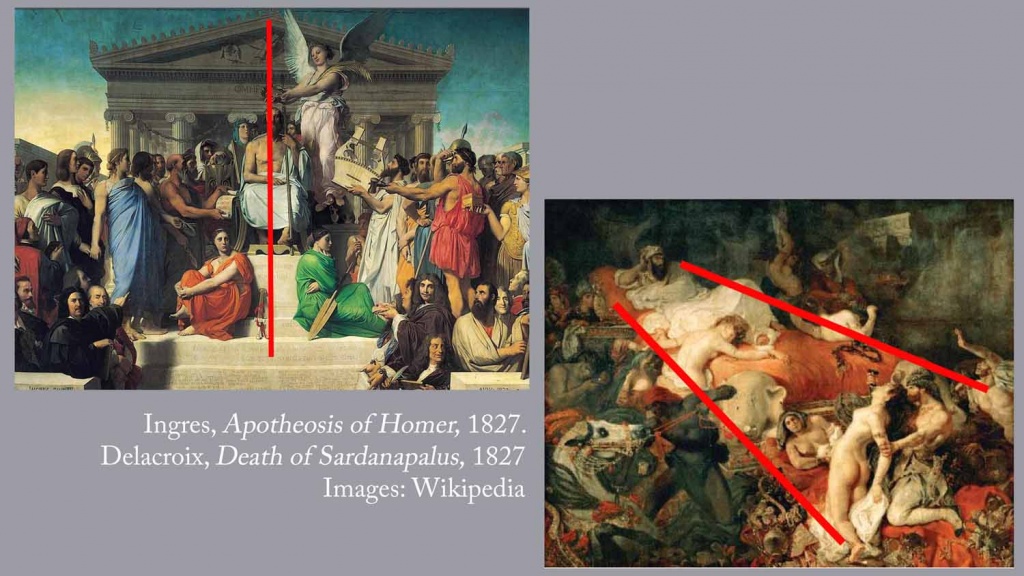

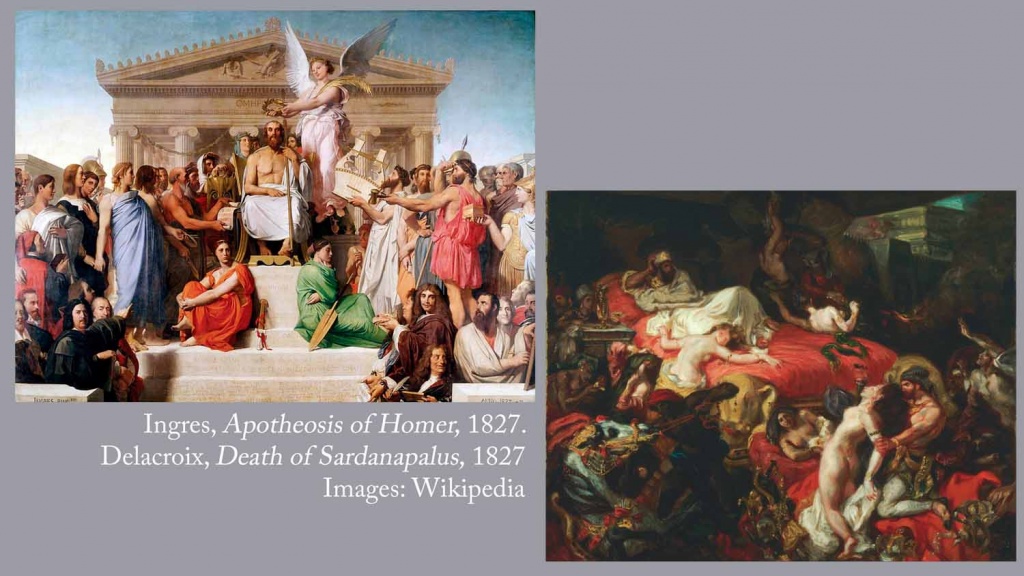

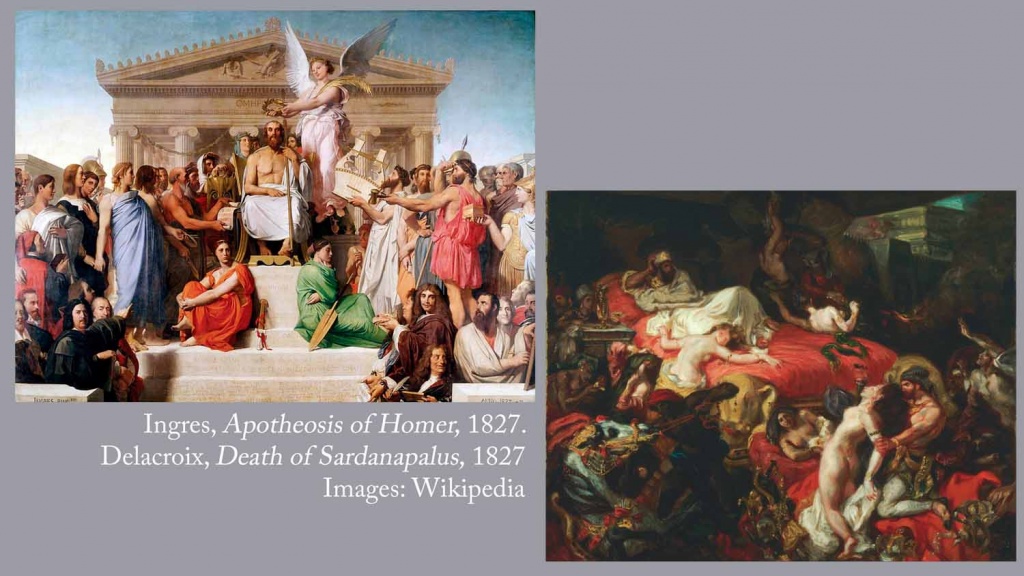

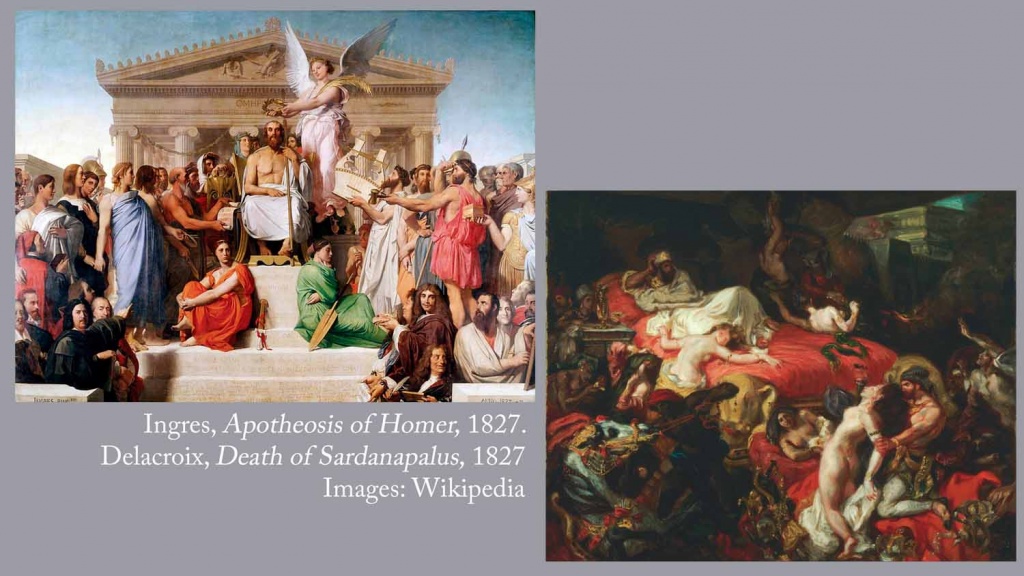

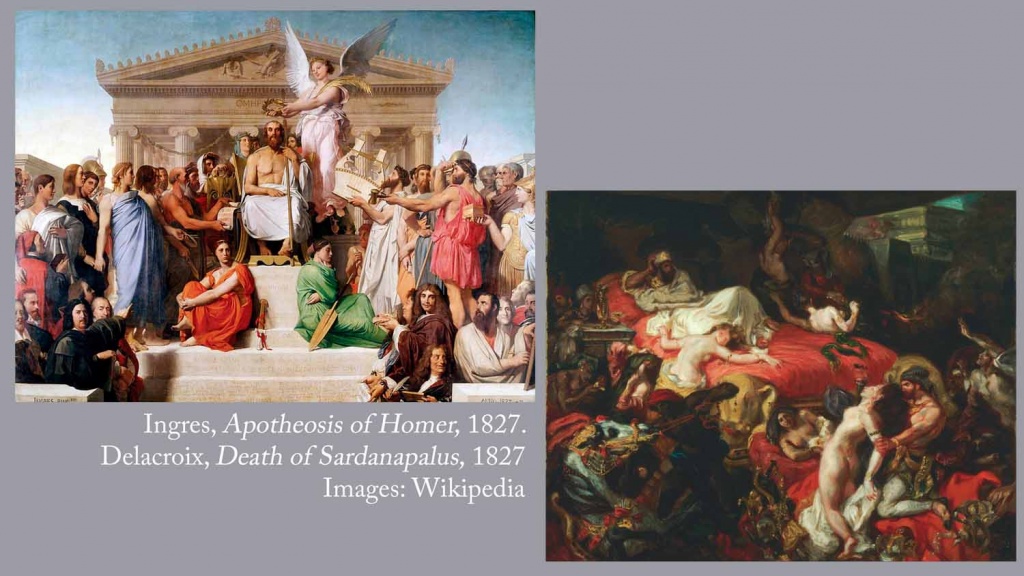

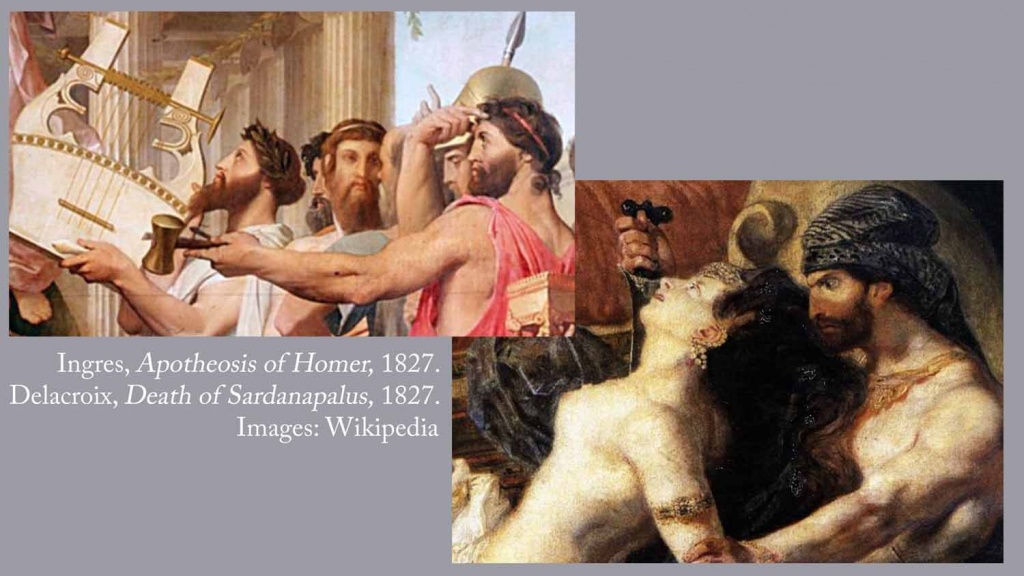

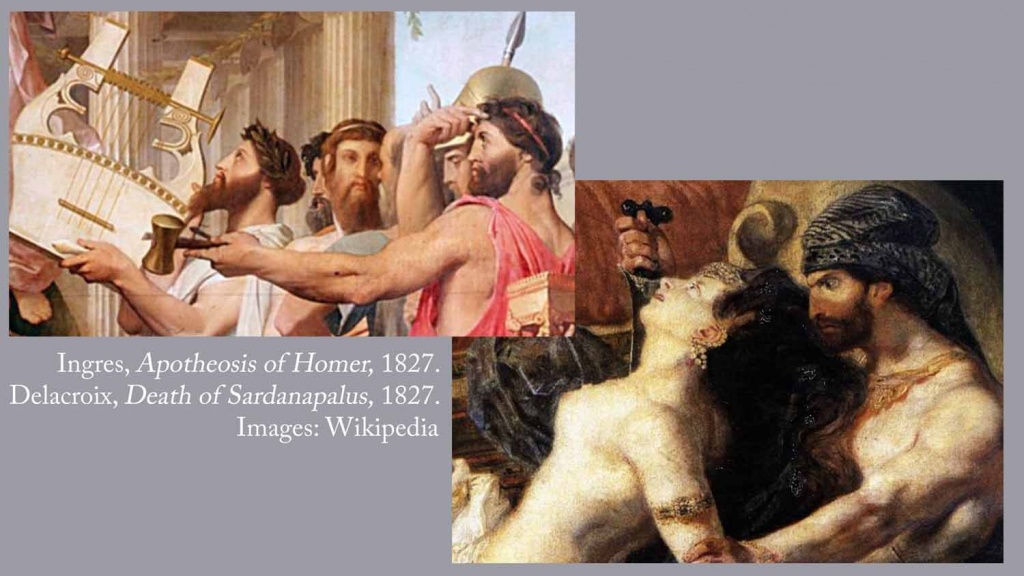

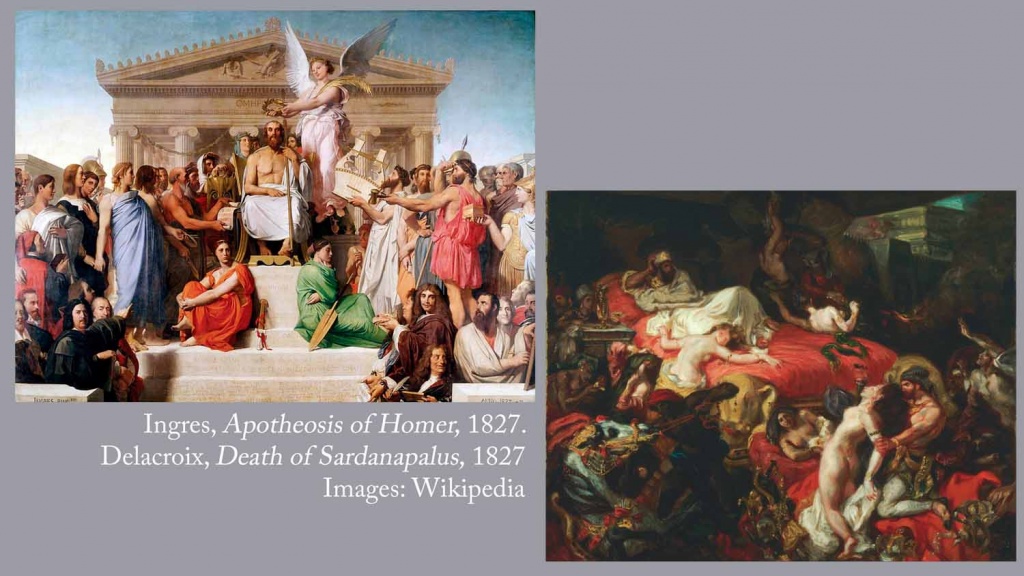

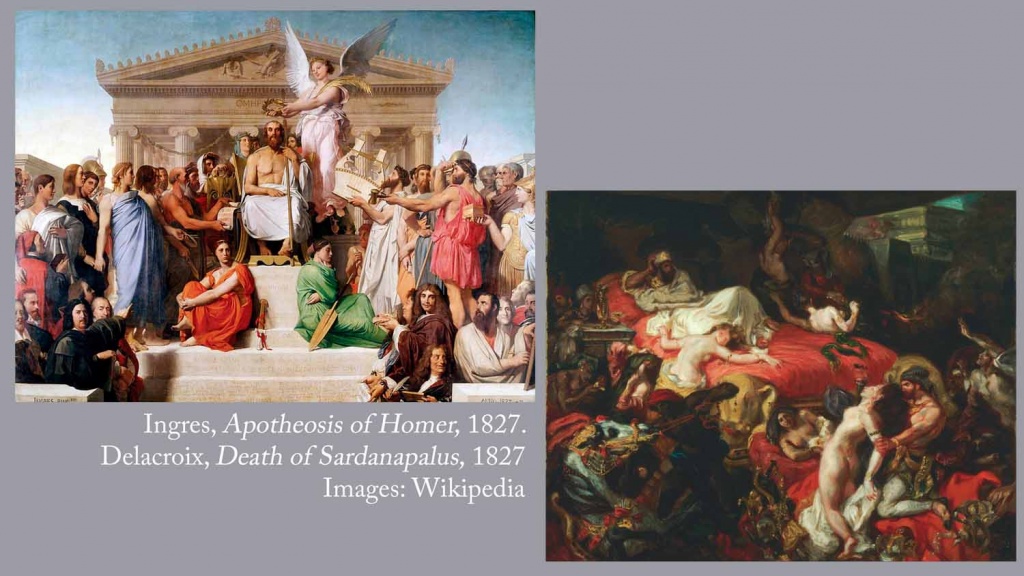

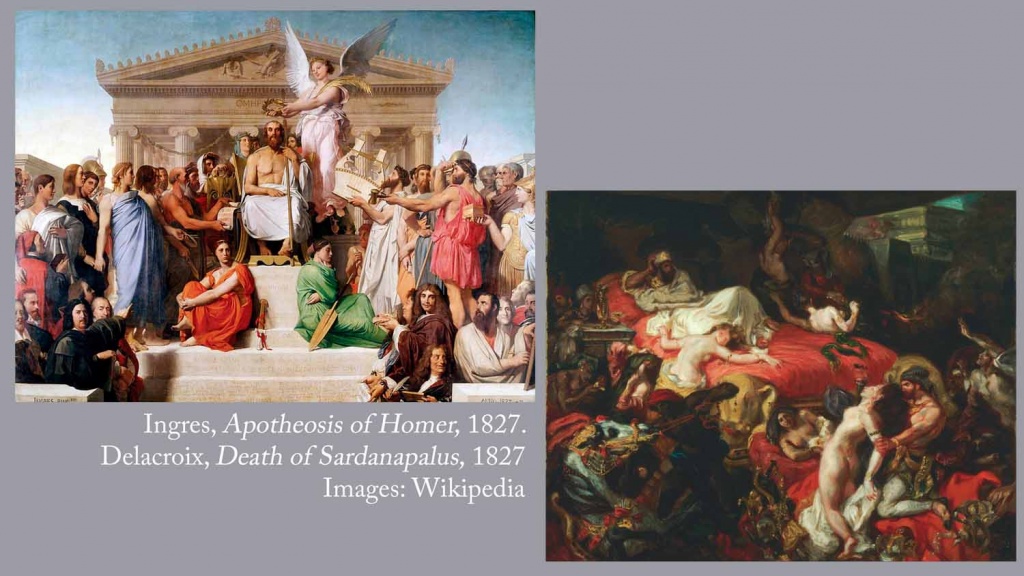

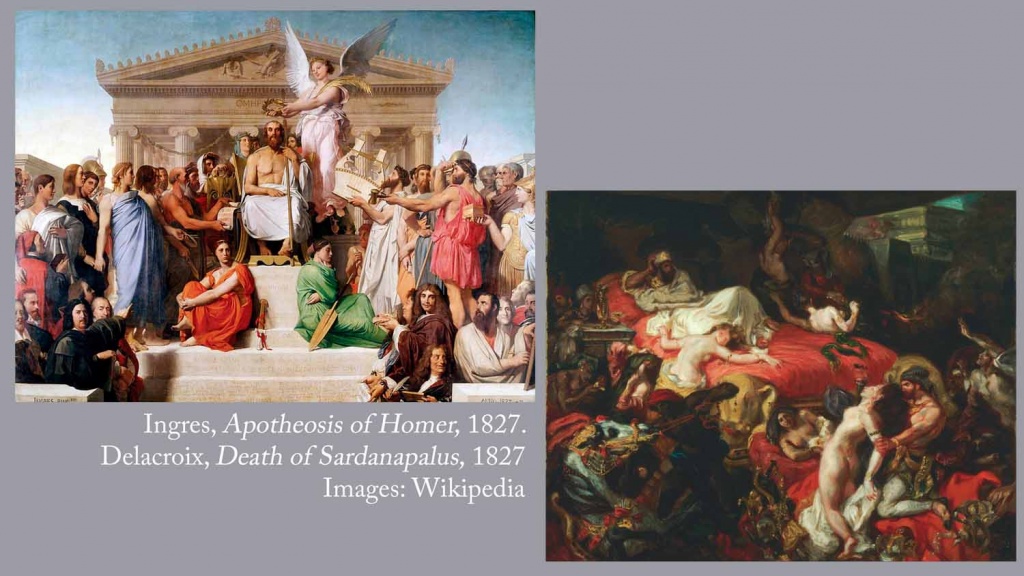

Ingres’s Apotheosis of Homer, 1827, and Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus, 1827 vividly illustrate the differences between the Neoclassicists and the Romantics. Seldom have two such radically different paintings been produced in the same city, within a year of each other. And each was an unmissable size, about 13 x 16 feet. (The Met’s Delacroix exhibition has a sketch of the Death of Sardanapalus and a small-scale reproduction painted by Delacroix. The original is too huge to travel transatlantic.)

The Apotheosis of Homer shows the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey as a genius to whom all ancient and modern artists pay homage. Homer and his admirers are arranged in front of a classical Greek temple, under a clear blue sky. The Death of Sardanapalus, on the other hand, shows a despot from ancient Assyria (modern Iraq) who, learning he was about to be conquered, ordered his henchmen to slaughter his harem girls and his horses so no one else could enjoy them. Sardanapalus, reclining at the upper left, impassively observes a maelstrom of death and destruction.

The styles as well as the subjects of these two paintings are diametrically opposed. Ingres’s composition is balanced and symmetrical, with a strong focal point established by the temple’s pediment and by the central placement of Homer and the angel who crowns him.

Delacroix’s composition has two long diagonals that move the viewer’s eye back to Sardanapalus’s reclining figure. The rest of the scene is asymmetrical, full of chaotic movement.

In the Ingres painting, the light pours in from our left, casting few deep shadows. In Delacroix, the room is dimly lit and full of shadows, making the scene even more turbulent and confusing.

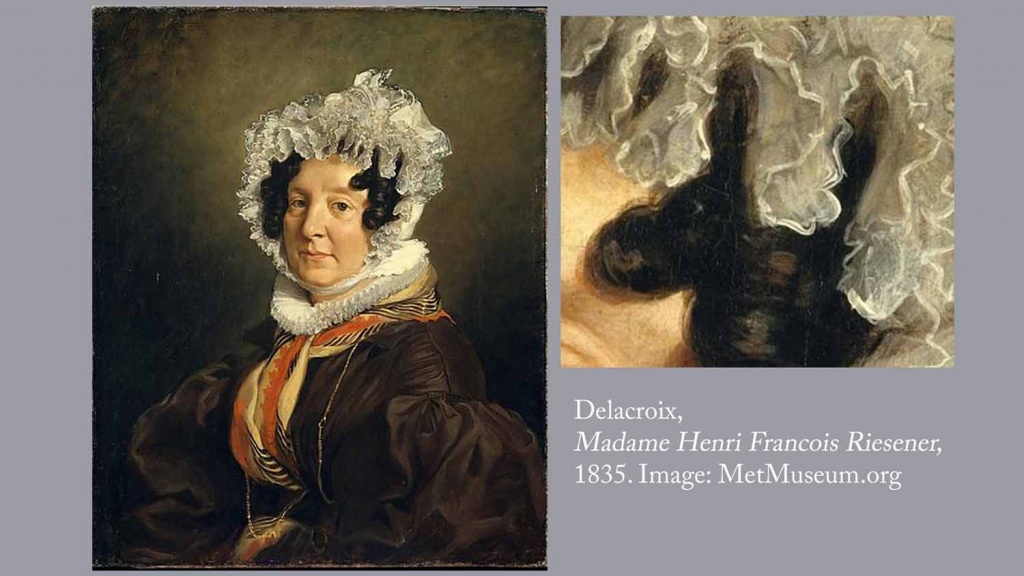

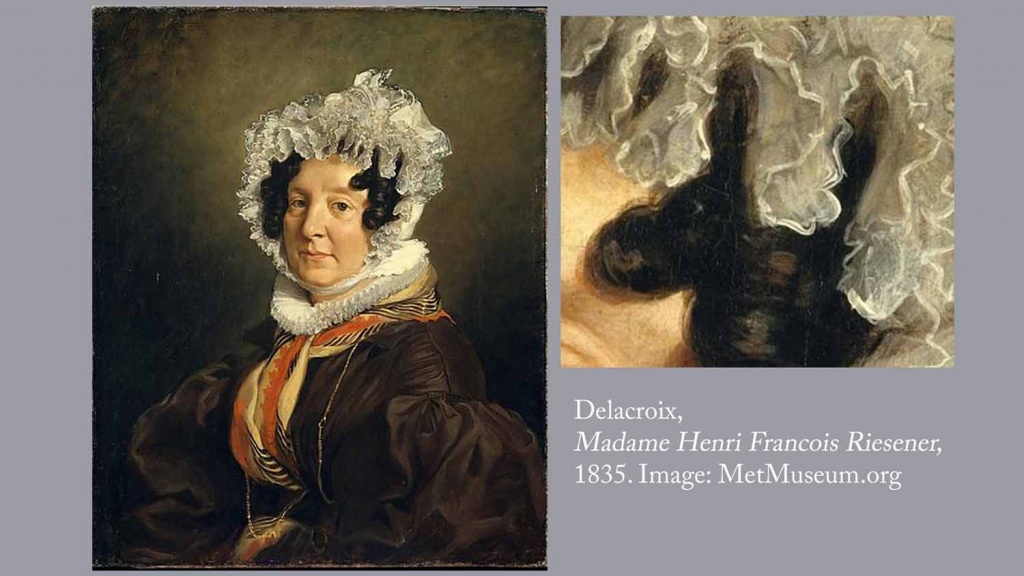

Side note: Delacroix was capable of executing a flawless finish, when he considered it appropriate for the subject. In a portrait of his aunt, he depicted the facial features with precision but the lace of her headdress with a very free hand.

For Ingres and the other Neoclassicists, the purpose of art was didactic: to depict truth and beauty, and thus to teach the viewer how to be a better, more moral person. The restrained, low-key mood is appropriate for such an intellectual aim. For Delacroix and the Romantics, the purpose of art was to evoke a strong emotion – in Sardanapalus, a dozen variations on terror. A gloomy and chaotic style was appropriate for that goal.

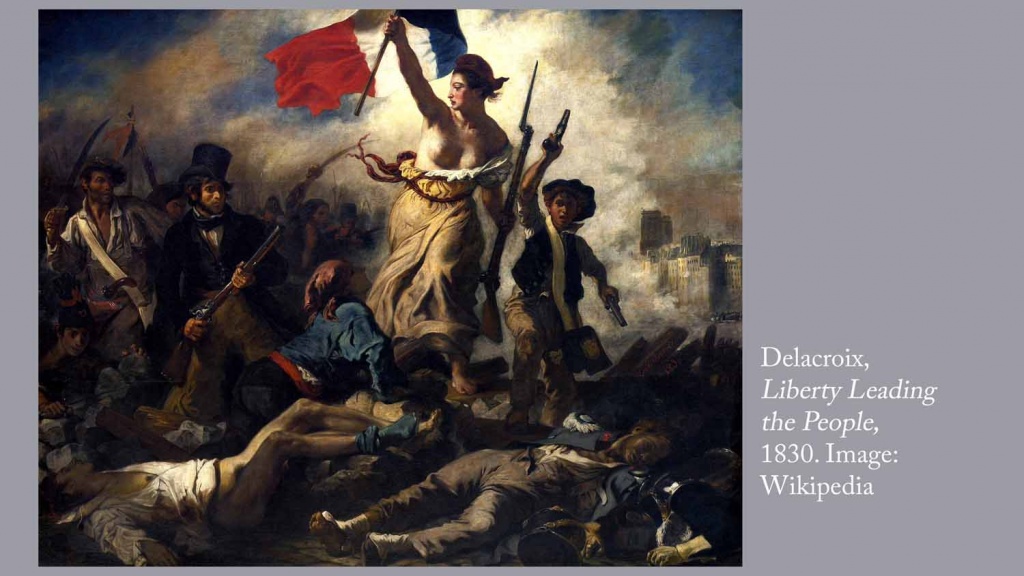

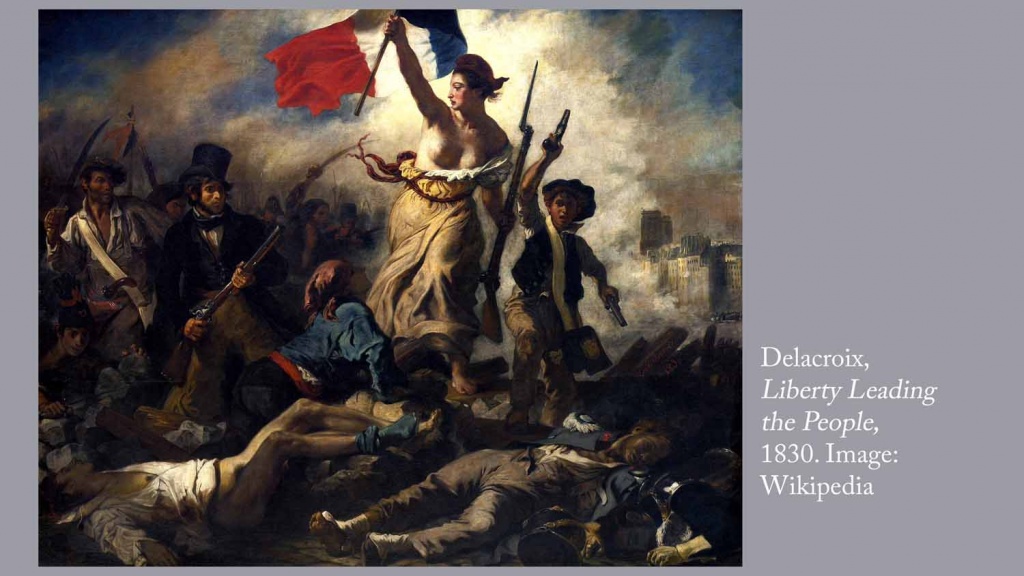

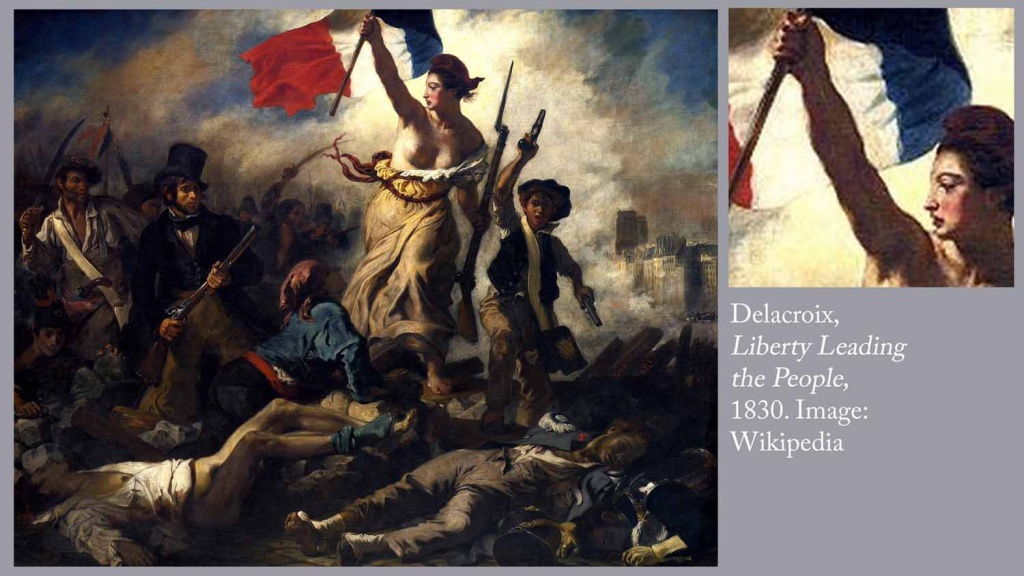

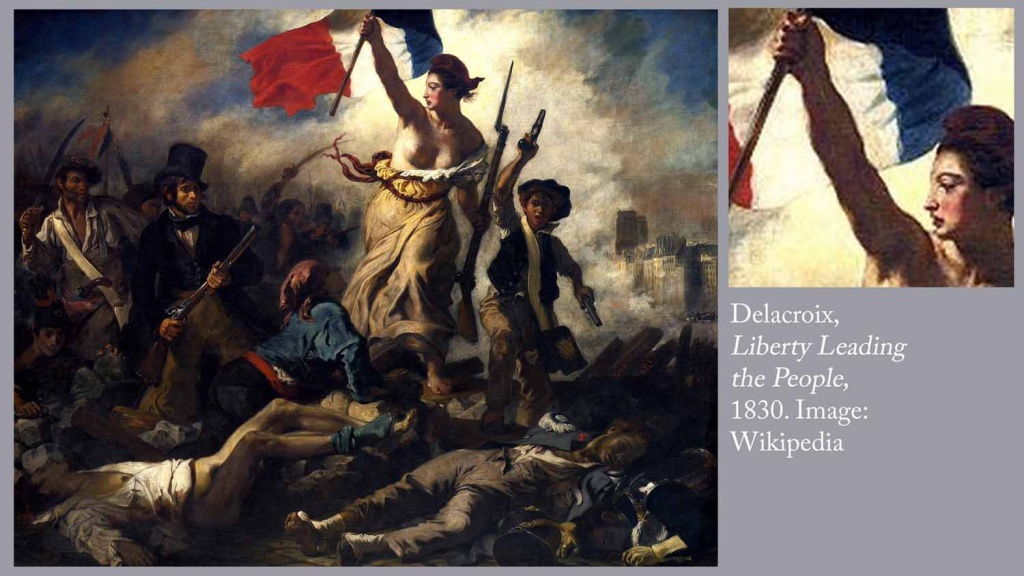

Evoking emotion is what Delacroix did best. In one of his most famous paintings, Liberty Leading the People, 1830, Delacroix showed common people in a dramatic situation, as Géricault had done.

Here, in a commemoration of one of Paris’s many rebellions against royal authority, the allegorical figure of Liberty triumphantly leads Parisians across piles of corpses and rubble. At the left, Delacroix included a self-portrait in a top hat. The boy on the right is often regarded as the inspiration for Gavroche in Hugo’s Les Misérables. (Bellos points out in The Novel of the Century that the boy is wearing a student’s cap, and Gavroche was a student only of the streets.) As in the Death of Sardanapalus, Delacroix here favors blurred details and murky colors.

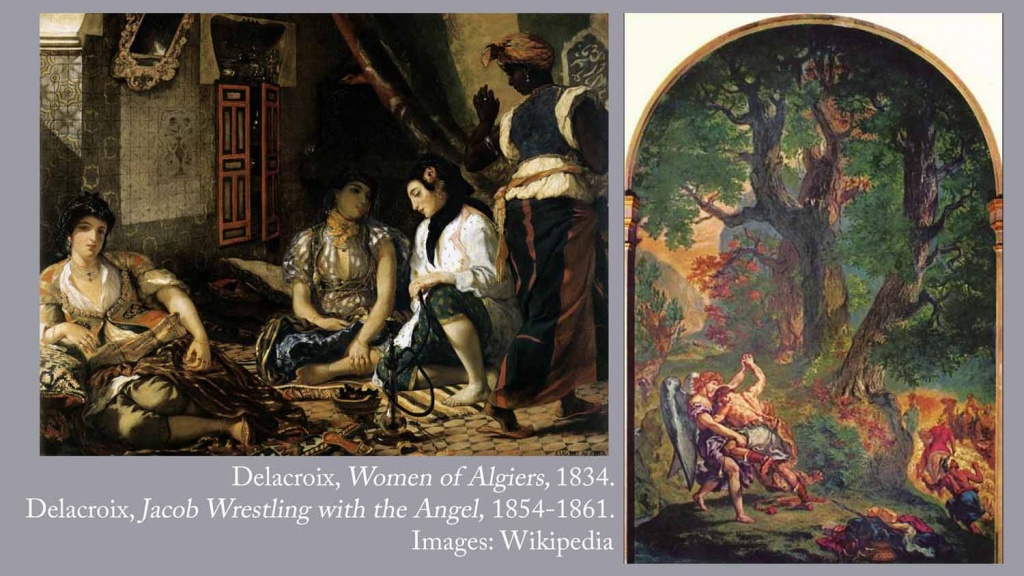

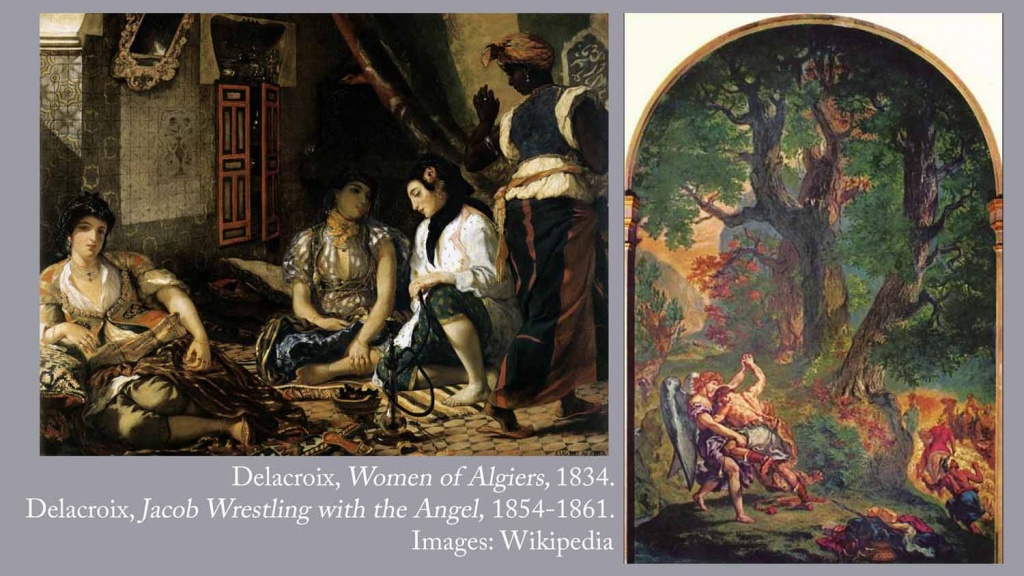

Delacroix seldom painted such contemporary events. He favored instead exotic milieus, religious subjects, and scenes from authors such as Shakespeare, Byron, and Sir Walter Scott.

In these, Delacroix used a brighter palette, but even here his colors are murky compared to the clear hues of Ingres. Murky colors and blurry details are characteristic of Delacroix’s style throughout his career.

Delacroix discusses art

What did Delacroix have to say on the issues that we are following regarding art and philosophy?

In 1853, Delacroix wrote:

Nature is far from being always interesting from the standpoint of effect and of ensemble. If each detail offers a perfection which I shall call inimitable, these details collectively, on the other hand, rarely present an effect equivalent to the one which results, in the work of the great artist, from the feeling for the ensemble and the composition.

Selecting details and arranging a composition implies that conscious thought has a role in the creation of art. Delacroix’s assertion that artwork conveys a message confirms this:

Is there not a moral attached even to a fable? Who should reveal this better than the artist, who plans every part of the composition beforehand in order that the reader or beholder may unconsciously be led to understand and enjoy it.

But Delacroix also saw emotions as invaluable, and disparaged rational thought when painting:

I do not at all like reasonable painting. I recognize that it is necessary for my turbulent mind to be agitated, to destroy its bonds, to try out a hundred manners before arriving at the goal, the need for which torments me in everything. There is an old leavening, a pitch-black depth to satisfy. If I am not agitated like a serpent in the hands of a pythoness, I am cold. This must be recognized and be submitted to; and this is a great pleasure. Everything that I have done well has been done in this way.

It is no wonder that Ingres, a highly cerebral painter, regarded France’s most famous Romantic as the devil incarnate. Passing Delacroix at an exhibition he growled, “I smell sulfur.”

Baudelaire and Delacroix

We now turn briefly to a man who is not an artist but an art critic – a relatively new phenomenon. During the 19th century, several factors combined to make art critics enormously influential. Due to the Industrial Revolution, the standard of living was rising, and more people could afford to purchase art. Increased wealth and productivity also led to widespread literacy and greater leisure, after centuries when most people had struggled from dawn to dusk for mere subsistence. Inventions such as the steam-powered printing press, wood engraving, photography, lithography, and inexpensive wood-pulp paper made it easier and faster to transmit ideas and images. More people than ever saw and read about the latest developments in art.

Yet there were still no accepted standards for judging art. This provided the perfect breeding ground for the emergence of professional art critics, who made it their mission to tell the public which type of art they ought to approve of. Critics’ reviews of the Paris Salon exhibitions were printed in periodicals and circulated widely in pamphlet form.

Among the critics who achieved lasting fame were Baudelaire (1821-1867), Ruskin, and Zola. It’s Baudelaire who matters for Delacroix.

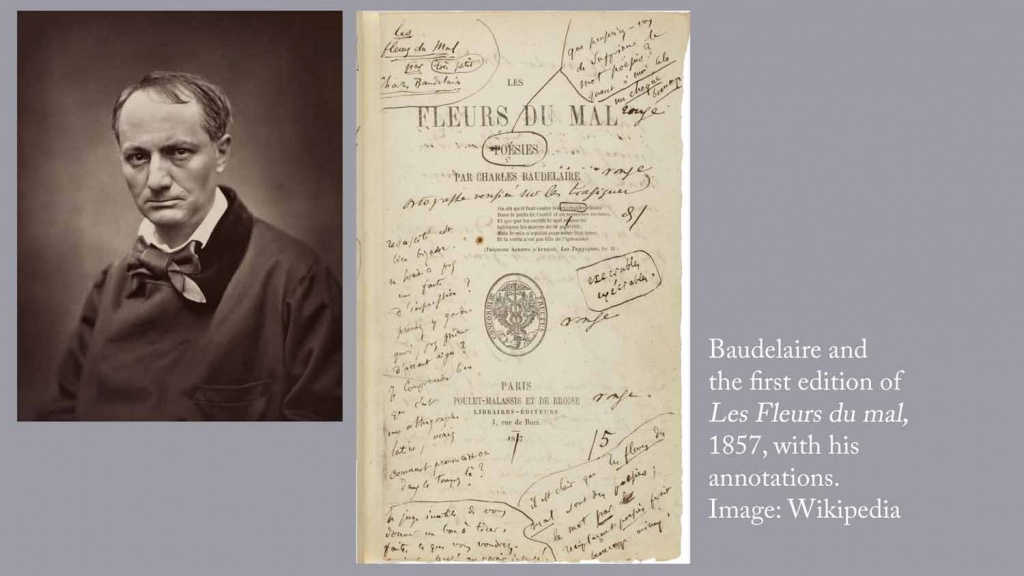

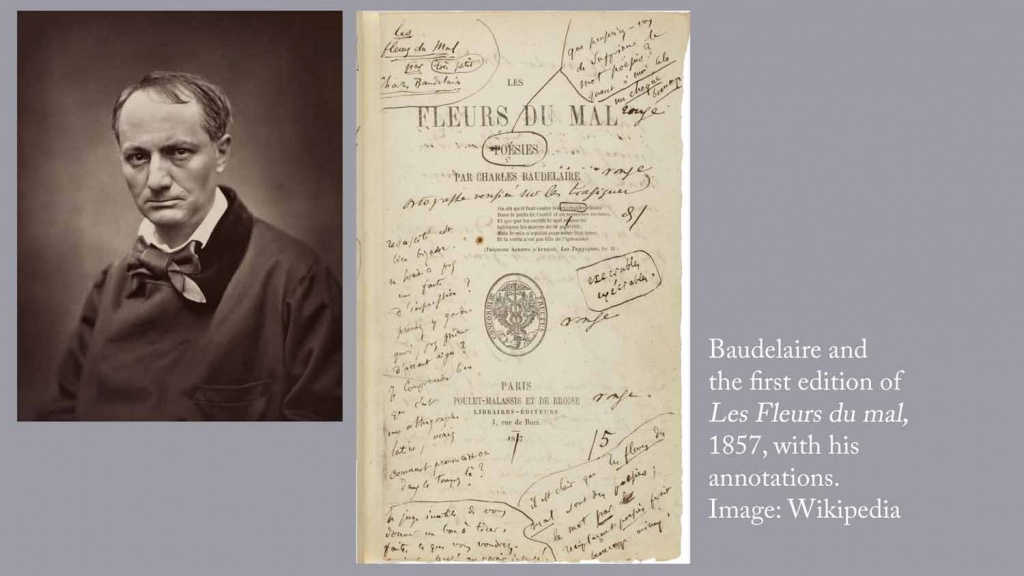

Baudelaire was born in 1821, about the time Romanticism burst onto the French art scene. He died in 1867, the same year as Ingres died. Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil, 1857, was arguably the 19th century’s most influential collection of poetry.

The opening lines of Flowers of Evil, addressed to his readers, reveal Baudelaire’s horrendous sense of life:

Stupidity, delusion, selfishness and lust torment our bodies and possess our minds, and we sustain our affable remorse the way a beggar nourishes his lice.

Baudelaire’s published comments praising Delacroix boosted Delacroix’s fame and influence. In fact, much of what is accepted as the Romantic attitude toward art was actually Baudelaire’s interpretation of Delacroix.

Regarding Delacroix’s style, Baudelaire said:

From Delacroix’s point of view, line does not exist; for no matter how thin it may be, a maddening geometer can always suppose it thick enough to contain a thousand others; and for colorists, who seek to imitate the eternal palpitations of nature, lines are never other than the intimate blending of two colors, as in the rainbow.

If you peer intently at Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (or many of the paintings in the Met’s Delacroix exhibition), the outlines actually seem to vibrate.

What makes Delacroix distinctive, according to Baudelaire, is not a style or subject but an emotion – a feeling, rather than a way of thinking or acting:

There remains for me to note one last quality in Delacroix to complete this analysis, the most remarkable quality of all and one that makes him the true painter of the 19th century: it is the singular and obstinate melancholy that runs through all his works, and that is expressed in his choice of subject, by the expression of his faces, through gesture, and in his kind of color.

In his obituary of Delacroix, Baudelaire pithily summed this up:

Delacroix was passionately in love with passion, and coldly determined to seek the means of expressing it in the most visible way.

More

- The original version of this essay appeared in The Objective Standard, vol. 1, no. 3 (Fall 2006). I published it as a Kindle book in 2012: Seismic Shifts in Subject and Style: 19th-century French Painting and Philosophy. If you’re interested in the development of French art during the 19th c., check it out. The Kindle version includes all the footnotes and the sources of the images.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.