Introduction

I find Reflecting Absence, the memorial on the site of the World Trade Center, profoundly unsatisfying. If you do, too, this essay will help you understand why landscape architecture and a list of names don’t make for a memorable memorial.

NOTE: Click “Portraits to Puddles” in the Obsessions cloud to see all the posts in this series. The illustrations are from the video, available here. The complete series is also available in print and as a Kindle book: details in this post.

Today most of us remember vividly the events of 9/11, and we are deeply moved when we stand at the site of the terrorist attacks. But a hundred years from now, no one alive will remember the smiles of loved ones setting out to work on that bright September day in 2001. No one standing at the site will remember what he or she was doing when the Towers fell, and the world changed.

What will Reflecting Absence say then? What will the pools, trees, and lists of names tell our great-grandchildren about how we want to remember the people who died that day? Surely we can offer the victims of 9/11 a better tribute than a gloomy park that lingers like a scar in the business district of one of the world’s great cities.

But what makes an effective tribute? What makes a memorable memorial?

One easy way to grasp the possibilities is to look at what previous generations have erected as memorials. The many sculptures in nearby Battery Park provide some excellent examples of memorials created over the past hundred years. In this essay, I’ll point out the lessons we can learn from half a dozen of them that can be applied to a memorial for the World Trade Center – and I’ll explain how our memorials declined from portraits to puddles.

This essay is based on a walking tour that I gave in 2003 – when the competition was being held for the World Trade Center memorial – of sculptures in Battery Park and the southern end of Manhattan. Since 2012, it’s been available as a Kindle book: From Portraits to Puddles: New York Memorials from the Civil War to the World Trade Center Memorial (Reflecting Absence). The essay will be spread out over a series of blog posts: click “Portraits to Puddles” in the Obsessions cloud to see them all. When all the parts have appeared, it will also be available as a video on YouTube.

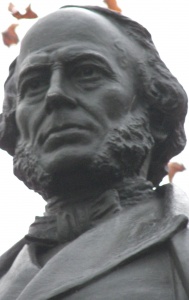

John Ericsson

Our first stop is a portrait sculpture of John Ericsson. It’s toward the east side of Battery Park, near the Starbucks on State Street. Since the sculpture is 10 feet tall and stands on an 11-foot pedestal, you shouldn’t have trouble spotting it.

The Parks Department has provided a historical marker that tells you all about Ericsson. Resist reading it for the moment: it’s better to look at a sculpture without preconceptions.

The Ericsson sculpture

Looking at Ericsson from the west, what we notice first is his posture: spine upright, shoulders back.

Moving around to the front, we can see from his expression that he’s serious, even frowning slightly.

The strange object in his left hand suggests that he deals with something mechanical.

The device peeking out of his breast pocket – a compass, maybe? – also suggests something mechanical, mathematical or scientific.

The roll of papers in his right hand suggests that whatever he works on, it’s complex enough to require a lot of blue prints or specifications.

It may be news to you that you can look at details of a sculpture and make such deductions about the subject. In fact, this is the nature of art in general and portrait sculptures in particular. Because this work was created by an artist from scratch, we can assume that every detail is there for a reason: to tell us something about Ericsson. If he’s standing straight and tall, rather than hunched from decades of leaning over drafting tables, that’s significant. If he’s holding a model rather than an umbrella, and his pocket holds a compass rather than a handkerchief, that’s significant as well.

Together the details of this portrait sculpture tell us that Ericsson was confident, that he worked in some sort of mechanical field, and that he takes his work seriously. (In Getting More Enjoyment from Art You Love, I discuss at much greater length how to observe the details of a sculpture and figure out their significance.)

Let’s get back to that strange object Ericsson holds. It’s a model of the invention that he’s most famous for, the ironclad warship Monitor. The battle of the USS Monitor and the CSS Merrimac in March 1862 was a crucial event in the Civil War. I want to set the context for that battle by giving you some background on naval warfare and Ericsson’s career as an engineer.

Naval propulsion and naval warfare

Recall what you know of the early 1800s. How were warships propelled? Think of Horatio Hornblower. If you’re better on history than on TV and movies (which would make you quite rare and admirable these days), think about the Battle of Trafalgar in the Napoleonic Wars.

Ships at that time were propelled by sails: big, billowing sails that had to be hauled up and down by hand, and that would move the ship only if the wind blew.

And how did such ships attack the enemy? They shot cannonballs – big lumps of metal – from a row of guns along the side of the ship.

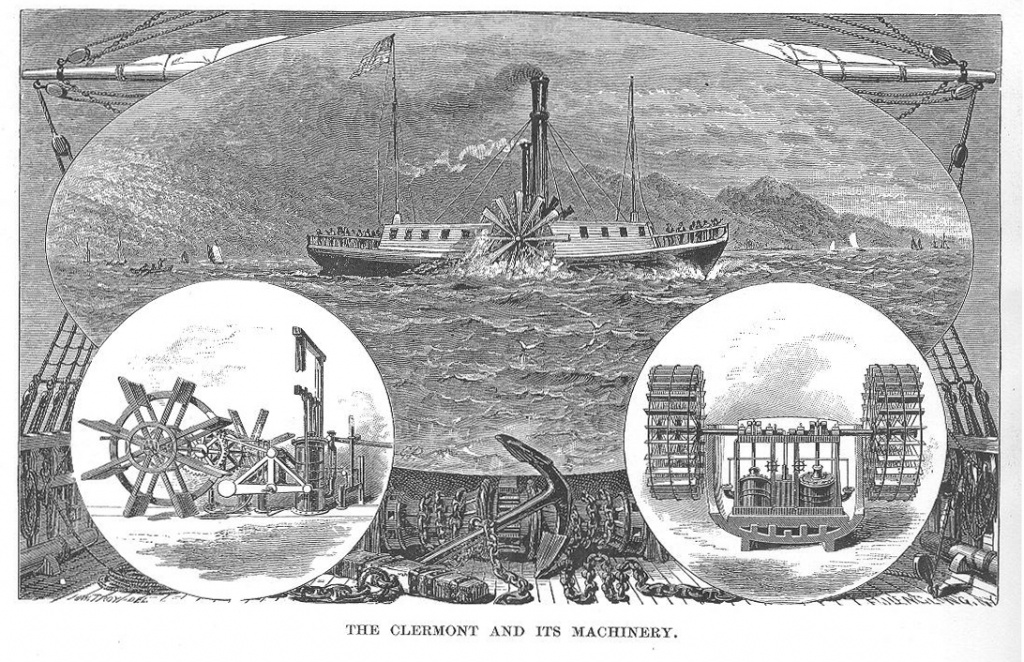

In the 1810s came a major technological advance: the use of a steam engine to move a paddlewheel that drove the ship.

This was the biggest advance in propulsion since the 15th century, when the Portuguese added a movable, triangular sail to square-rigged ships and thereby made the Age of Exploration possible.

The advantages of a steam engine will be obvious if you’ve ever spent an windless afternoon bobbing up and down on a sailboat, or if you’ve tried to sail in one direction while the wind resolutely blew from the opposite quarter. Steam power made ships much faster and much more maneuverable.

The next major development in naval warfare was artillery shells. A shell isn’t solid metal or stone like a cannonball. It has an explosive charge inside. Shells had devastating effects on wooden-hulled ships, and especially on their paddlewheels, which made easy targets.

Now we come to Ericsson. By the 1830s, Ericsson had conceived a screw-propelled vessel. The propellers were beneath the water line, like those of a modern motor boat. The United States Navy learned of Ericsson’s idea and hired him to design a screw-propelled warship. So Ericsson moved from Sweden to New York, where he spent the rest of his life and became a familiar sight.

Ericsson as fire-fighter

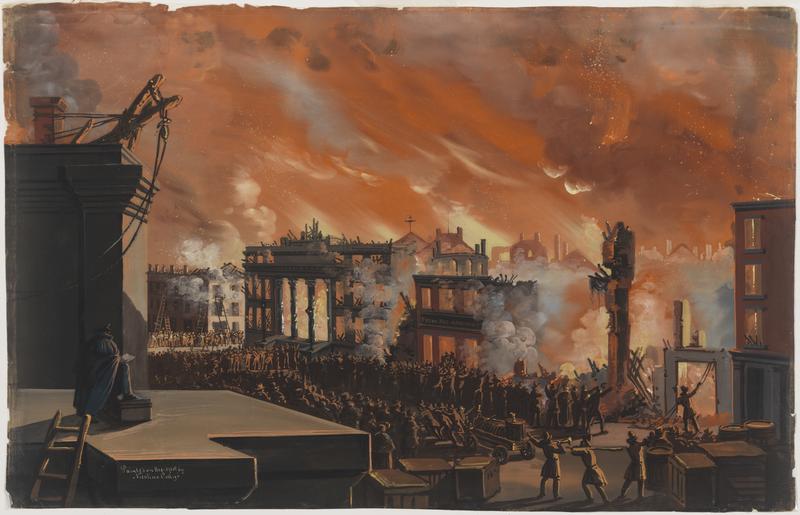

Ericsson arrived in New York in 1839. Four years earlier, the Great Fire of 1835 had destroyed 600 buildings in lower Manhattan. One of them was the Merchants’s Exchange, with its brand-new, fifteen-foot-tall marble sculpture of Alexander Hamilton.

In 1840, while the screw-propelled warship was in the works, Ericsson won a competition for a steam-driven fire engine that threw water much farther than firemen with buckets could. He helped solve a problem that terrified New Yorkers. Face the Ericsson sculpture and walk around the pedestal to your left. The relief there shows Ericsson’s steam-powered fire engine in use.

Screw-propelled warships

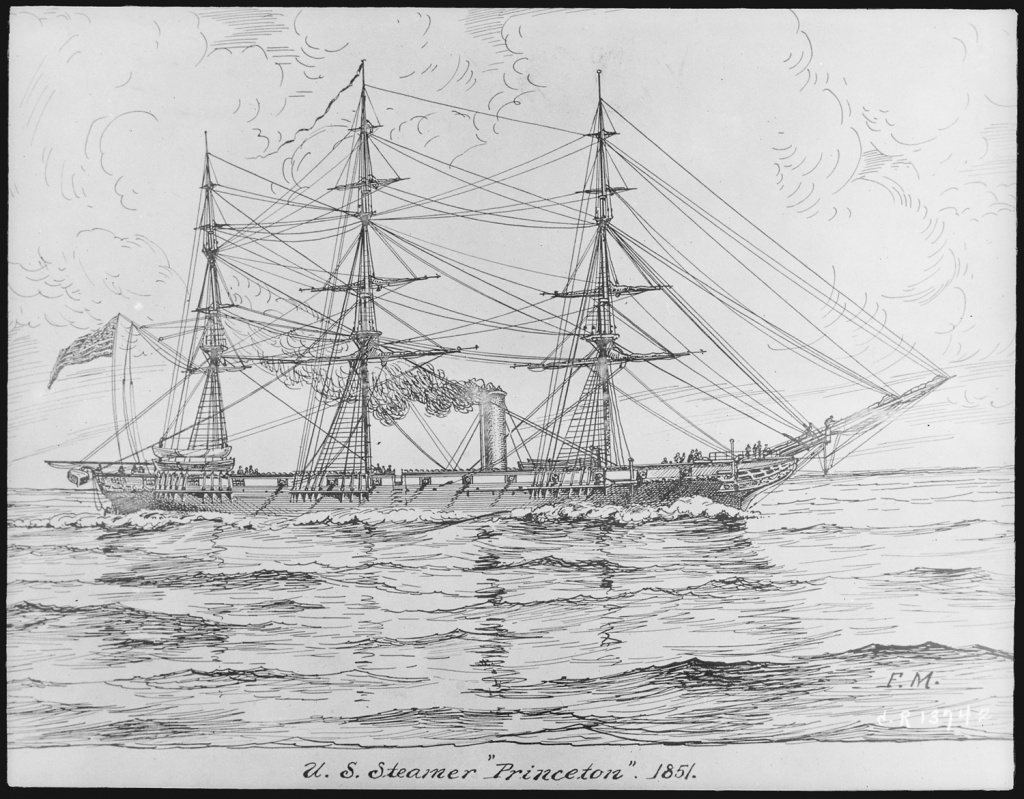

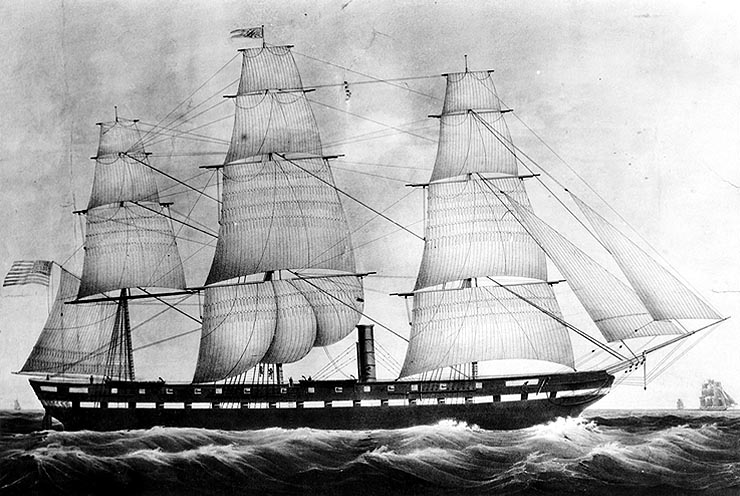

The relief on the front of the pedestal shows Ericsson’s screw-propelled warship, the USS Princeton.

The Princeton was a hybrid vehicle. It has sails (quite a lot of them) as well as a steam funnel in the center. The sails were probably a back-up system in case something went wrong with that new-fangled engine and propeller.

When she was launched in 1843, the Princeton was the most formidable warship in the world.

She had a 12-inch gun that could launch a 225-pound projectile five miles. Imagine the damage that could do to a wooden-hulled ship at close range!

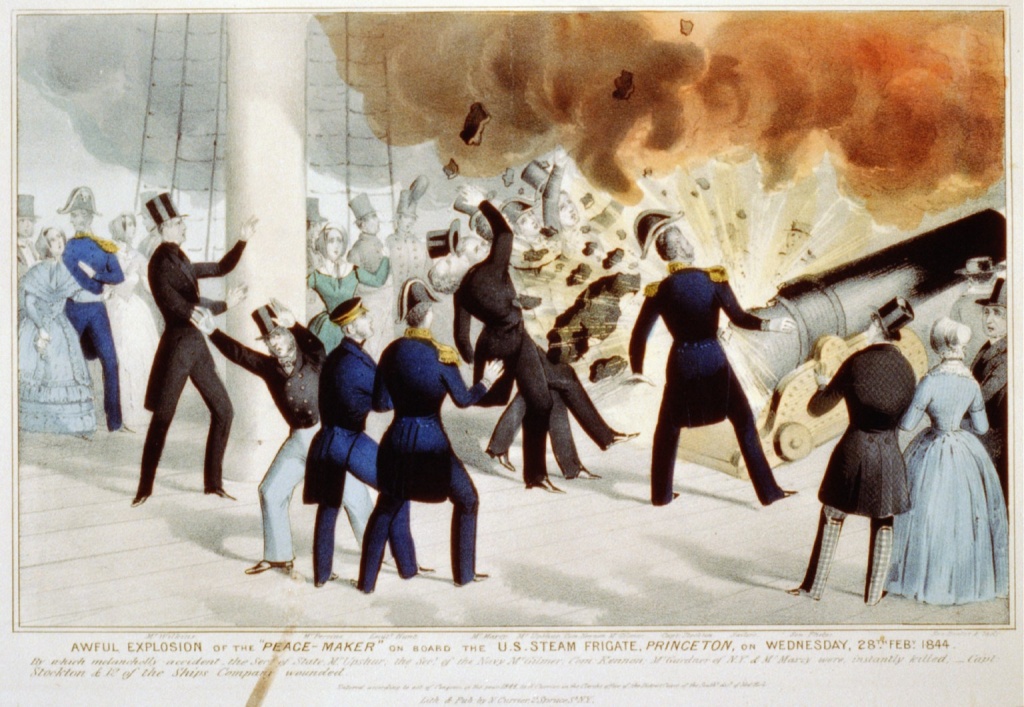

Unfortunately, Ericsson’s colleague Capt. Robert F. Stockton also designed a gun for the Princeton … and he designed it badly. During the Princeton’s trials Stockton’s gun exploded, killing the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of State, and the father of President Tyler’s fiancée.

Stockton managed to shift the blame to Ericsson and to arrange that Ericsson not be paid for his work on the Princeton. Through the 1850s, Ericsson lived in New York, worked as an engineer, pursued his own research on naval warfare – and kept his distance from the U.S. government.

By 1861, when the Civil War began, screw-propelled vessels like Ericsson’s Princeton were still state-of-the-art in naval warfare, but the artillery shells then in use could wreak havoc on such wooden-hulled vessels.

The ironclads

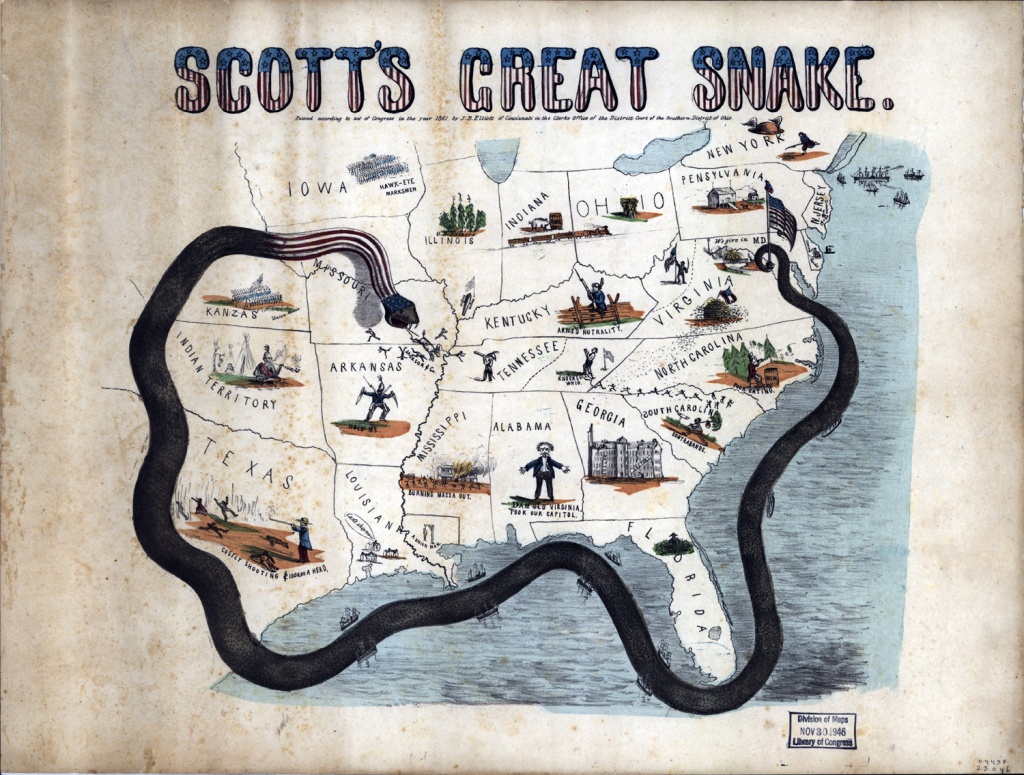

Now we shift our attention from New York to Virginia. As part of a strategy devised by General Winfield Scott, the Union was blockading the Confederacy’s ports, cutting Southerners off from trade and from outside assistance. The largest port in the South was Hampton Roads, Virginia. In this contemporary cartoon, Hampton Roads is near the tail of the snake.

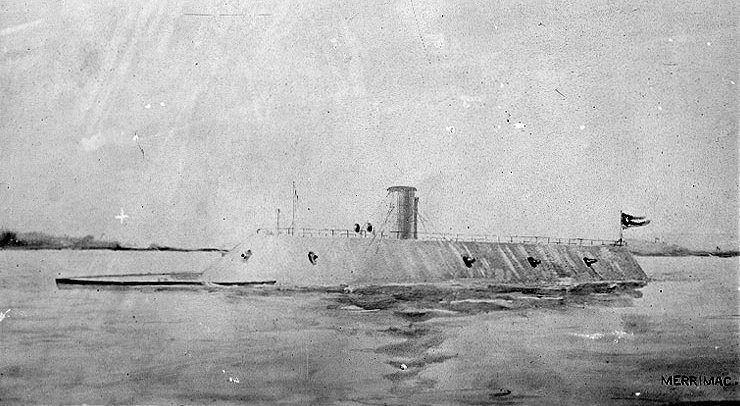

When the South seceded late in 1860, several US Navy ships were trapped in Hampton Roads. Union sailors burned and sank them so the ships wouldn’t fall into Confederate hands. One of those ships was the screw-propelled Merrimac.

The Confederates raised the Merrimac and covered her with iron plates. Salt water had severely damaged her engines. She sailed lopsided. Nevertheless, she was the most powerful warship afloat, because she could withstand artillery shells while bombarding her opponents. She was renamed the CSS Virginia, but since the Union won the war and wrote most of the histories, she’s usually still referred to as the Merrimac.

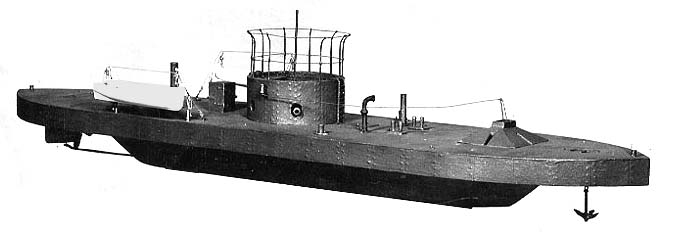

As soon as news of the Confederacy’s plans for the Merrimac leaked out, the United States Navy urgently requested proposals for an ironclad ship. Ericsson submitted a design for a radically new type of ship. Our Ericsson is holding a model of it.

It had the iron plates the Navy required, but its other features were Ericsson’s inspiration, based on years of experience as a naval engineer.

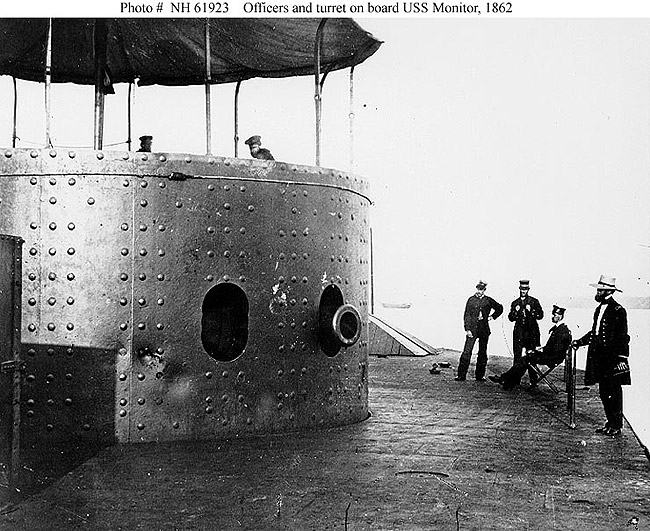

The ship was small, with a crew of only 58. (Some warships of the time had crews of 500.) Because of its steam engines and small size, the Monitor was very maneuverable. While it had only two guns, those two were very powerful and were set in a rotating turret. What made that idea so brilliant? A rotating turret meant the ship could fire in almost any direction. It didn’t have to maneuver broadside to the enemy.

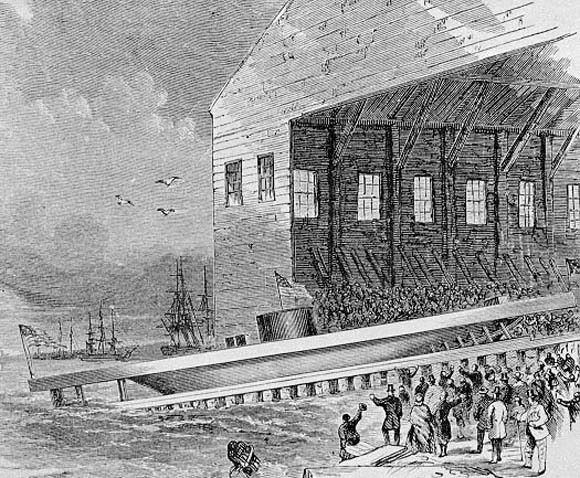

The Navy accepted Ericsson’s proposal for an ironclad. Ericsson supervised the construction of the prototype, coordinating work between three shipyards in Manhattan and Brooklyn, in the dead of winter, in a hundred days flat – at a time when no bridges connected Manhattan and Brooklyn. And he saw the ironclad successfully launched in front of a horde of skeptical New Yorkers who were certain an iron ship would sail directly to the bottom of the East River.

In early March 1862, as the Monitor wallowed southward through heavy seas, the telegraph flashed the news to New York and Washington that the Merrimac, on her maiden run from Norfolk, had rammed and sunk a fifty-gun Union frigate, set another on fire, and run a third aground.

In a single day’s battle, the Confederacy suddenly had the chance to break the Union blockade and become an international sea power.

Reports of this foray caused panic in Northern coastal cities. George Templeton Strong, a prominent New Yorker, wrote in his diary on February 27, 1862:

Sunday came the … disastrous tidings that the Merrimac was on the rampage among our frigates in Hampton Roads, smiting them down like a mailed robber-baron among naked peasants. General dismay. What next? Why should not this invulnerable marine demon breach the walls of Fortress Monroe, raise the blockade, and destroy New York and Boston? And are we yet quite sure that she cannot? — Strong, Diary, entry for 2/27/1862 (3:209-10)

Terrified New Yorkers instructed the Common Council to appropriate the enormous sum of $500,000 for harbor defenses, “at any sacrifice and at every hazard.”

Battle of the Ironclads

When the Merrimac returned the next day to finish her work, her crew saw what an eyewitness described as “an immense shingle floating on the water, with a gigantic cheese box rising from its center; no sails, no wheels, no smokestack, no guns.” The Monitor had arrived at Hampton Roads.

The Battle of the Ironclads on March 9, 1862, is one of the most familiar stories of the Civil War. It ended after more than four hours, when the Merrimac ran out of ammunition and lumbered away. Although both ships were largely unscathed, in the long term the battle was a Union victory. The blockade remained intact, and the Merrimac was bottled up at Hampton Roads.

Although Ericsson’s Monitor went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras later in 1862, her effect on naval warfare was profound. The British Navy – the most formidable in the world – cancelled all outstanding orders for wooden sailing ships. Iron plating, rotating turrets, steam power and screw propellers were to be the characteristics of the warship of the future.

The United States alone built 66 Monitor-type vessels. The last remained in service until 1925.

New Yorkers’ gratitude toward Ericsson for saving their city is expressed in the inscription on the back of the pedestal, which describes him as “a citizen whose genius has contributed to the greatness of the Republic and the progress of the world.”

If you haven’t read the Parks Department plaque on Ericsson, feel free to read it now. The text is available online.

Also take some time to look at the sculpture of Ericsson on your own. I haven’t discussed every detail of the figure and pedestal. Try focusing on one detail or one aspect such as Ericsson’s face or the textures used to represent hair, skin and cloth. How does that detail or aspect help convey Ericsson’s character? You may be surprised at how much you can observe, once you stop, look and think.

Lesson #1

This tour is a chronological survey, and we’ve now covered our Civil War memorial. Let me draw a lesson from it that we’ll later apply to the World Trade Center memorial.

This sculpture shows a man whose efforts helped win the Civil War. He holds a prop – a model of the Monitor – to help remind viewers of what his most important invention was. The reliefs on the base further explain his achievements.

So here’s our first lesson: The point of this sculpture isn’t to teach. If you want to know Ericsson’s biography, the words on the Parks Department’s plaque are far more effective than the sculpture. In a way that words on a plaque cannot do, however, this sculpture reduces Ericsson’s achievements to essentials, so that you can quickly understand and vividly remember what sort of man Ericsson was.

It’s a memorial. That’s what memorials do: they help us remember.

Your emotional response to this memorial comes from what you know about the man represented. If I told you that instead of a naval engineer, Ericsson was a slave-owning plantation owner, your reaction to the sculpture would immediately change. Emotional reactions come from what you see and what you know.

More on that in the next section of this essay. For the moment, remember that memorials are to help you remember, and that your emotional reaction comes from what you know about what you remember.

More

- This essay was provoked in 2003 by the competition for the World Trade Center memorial. I originally gave it as a walking tour of sculptures in Battery Park and the southern end of Manhattan. Since 2012, it’s been available as a Kindle book: From Portraits to Puddles: New York Memorials from the Civil War to the World Trade Center Memorial (Reflecting Absence). The end of the book has an illustrated, annotated list of 30 memorials in Manhattan dedicated to people whose job is to keep us safe: soldiers, policemen, firemen, and so on. If you want to see other memorials that are both effective and memorable, it’s a great place to start.

- The parts of the essay will appear as a series of blog posts: click “Portraits to Puddles” in the Obsessions cloud at right to find them.

- This blog post is available as a video to my recurring supporters. (Thank you!)

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.