This essay is adapted from Chapter 16 of Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. I’ve kept cross-references to other chapters in the book, all of which will eventually be updated and posted on this site. Click on “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan book” in the Obsessions cloud at lower right to see which are already here.

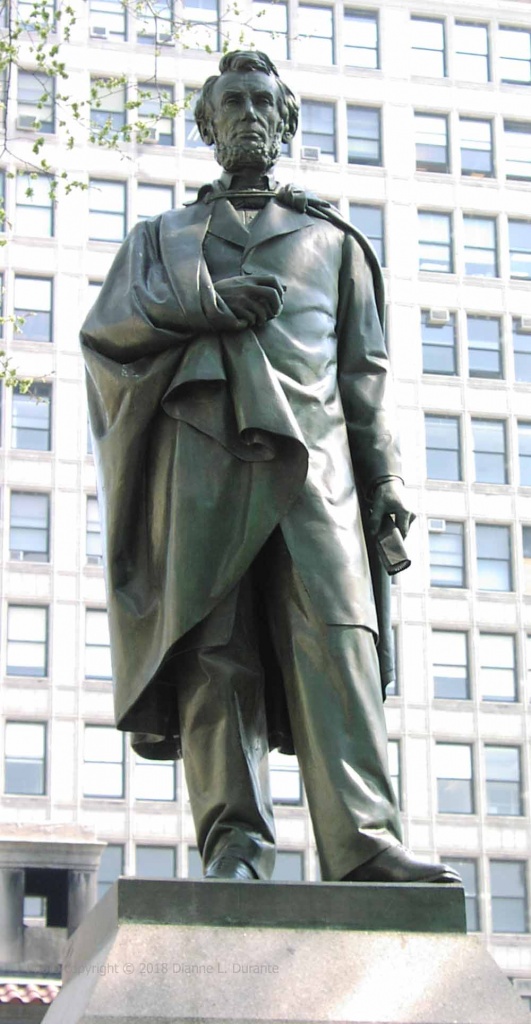

- Sculptor: Henry Kirke Brown

- Dedicated: 1870

- Medium and size: Bronze (11 feet), granite pedestal (approximately 14.5 feet)

- Location: North end of Union Square, on a line with 16th Street

About the sculpture

Ask any critic to name the country’s best statues of Abraham Lincoln, in purely artistic terms, and this statue won’t even make the short list. In a moment I’ll discuss which one would probably be chosen, but first: how can we judge the esthetic quality of this or any sculpture? Is there a way to do it rationally and objectively, rather than just making arbitrary assertions?

Whether you admire or detest Lincoln’s actions as president is irrelevant to a discussion of this sculpture in esthetic terms. Evaluating art as art means evaluating the means rather than the content: the “how” rather than the “what.” In turn, that requires knowing what art’s function is—otherwise we can’t say if it fulfills that function, or how well.

The function of art is to summarize an attitude toward the world, a sense of life, in a form so memorable that you can call it up in a split second when you need to reaffirm what you stand for. It’s not a substitute for observing the world. It’s not a substitute for thinking. It doesn’t tell you what principles to live by or for. A work whose sense of life agrees with yours, however, visually reminds you of what you consider important about man and the world. It helps you remember what you want to focus on, amid the innumerable impressions that assault your senses every minute of every day.

This connection between art and ideas explains why humans were creating art tens of thousands of years before they had written language, and why art created hundreds or thousands of years ago can still have such powerful emotional impact. (More on this in Chapter 8, on Hale.)

The function of art leads to two closely related esthetic requirements – requirements of art as art.

First, a work of art must be clear. We, as viewers, must be able to figure out what the piece is about and what the artist thinks about it. Michelangelo’s David shows a young, muscular man armed with a sling who seems relaxed (the stance) but also alert for an approaching danger (the frown lines). According to the Biblical story, he’s going to fight a giant and win. The message: with courage, strength, and alertness, you can triumph. The Hellenistic Laocoon Group shows a muscular man and his teenage sons desperately struggling against monstrous snakes. According to the myth, they were murdered because Laocoon told a truth that one of the gods didn’t want known. The message: you can be brave, strong, and honest, and still die horribly. We may disagree with the artist’s point of view, but the message in both cases is perfectly clear.

The second requirement of a work of art is that it be integrated. Every detail must help convey the message. None can lead the viewer off on a tangent by making him wonder what the devil it’s doing there. Imagine David wearing only one sandal, or Laocoon clutching a bouquet of flowers. For us as viewers, combining such disparate elements is like trying to fit the pieces of two different jigsaw puzzles together. As soon as we start worrying about why the artist included certain odd details, we stop seeing the work of art as a single, memorable image.

Now let’s return to Lincoln. The critics’ choice for best sculpture of Lincoln standing up would probably be Saint Gaudens’s Standing Lincoln in Chicago (1887).

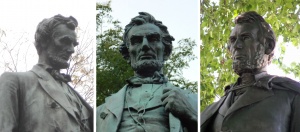

Brown’s and Saint Gaudens’s figures are both recognizable portraits of Lincoln. Both are dressed in appropriate period costume. Yet Saint Gaudens’s effort is esthetically superior, because it presents Lincoln’s character more vividly.

How? The head of Saint Gaudens’s Lincoln is bent, as if he’s deep in thought. His furrowed brow confirms that. Brown’s Lincoln gazes into the distance; we can’t read any emotion on his face.

Saint Gaudens’s Lincoln wears snugly fitting clothes that reveal his lean, angular body. The gauntness combined with the bent head and furrowed brow suggest that this is a man whose concerns are so pressing that he doesn’t have the time or the desire to eat.

Brown’s Lincoln wears looser garments that conceal his body. The cape looped over his arm, a neoclassical touch reminiscent of a Roman orator, gives Lincoln some time-honored associations and authority (see Washington, Chapter 6), but makes his figure even bulkier.

In pose and costume, Brown’s Lincoln could be any late nineteenth-century notable. The eminent rank of Saint Gaudens’s careworn Lincoln is indicated by the chair behind him, on which the American eagle spreads its wings. It’s a seat proper only for a president.

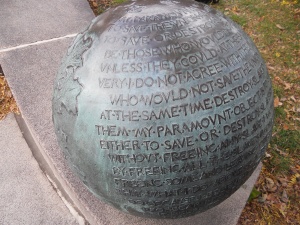

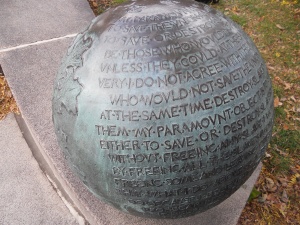

Saint Gaudens’s Lincoln has another advantage: it’s set in an large plaza that clears space in the park around it, suggests the importance of Lincoln, and offers two of his speeches.

In purely artistic terms, Saint Gaudens’s Lincoln is undeniably better than Brown’s, for the same reasons that Hartley’s second Ericsson (Chapter 2) was better than the languid earlier version, and Ward’s Greeley (Chapter 7) is better than Doyle’s. Its details make the sitter’s character more obvious; that makes it esthetically a better sculpture.

Note that how we react to a sculpture emotionally is a different matter from how we evaluate it esthetically. On emotional evaluation, see Booth and Conkling (Chapters 17, 18).

About the subject: Lincoln, Vallandigham, and Habeas Corpus

In March 1863, the third year of the Civil War was about to begin. After a series of devastating defeats, the number of volunteers for the Union Army had slowed to a trickle. Congress passed and Lincoln signed the Enrollment Act, which authorized the draft.

Clement Vallandigham, a prominent “Copperhead” politician (a.k.a. a “Peace Democrat” or Southern sympathizer) closed a rousing speech in New York City with an exhortation to fellow Democrats: “He denied that we owe any obedience to our conscription act … We are under no obligation to respond beyond the limits of law constitutionally enacted” (reported in the New York Times). Two months later in Ohio, Vallandigham told another crowd that the war was “wicked, cruel and unnecessary – a war not being waged for the preservation of the Union, but for the purpose of crushing out liberty and establishing a despotism – a war for the freedom of the blacks and the enslaving of the whites.”

The Military Department of the Ohio included the state of Kentucky, a front-line zone. Vallandigham was arrested a few days after his speech on charges he had violated Union General Burnside’s decree that “the habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy will no longer be tolerated in this Department.” Vallandigham’s arrest caused a furor in Dayton, where telegraph lines were cut and the local newspaper office was torched.

Vallandigham was court-martialed, convicted and sentenced to close confinement in (horrors!) Boston. His lawyer promptly requested a writ of habeas corpus, which would have required Vallandigham’s appearance before a civil court to determine if he was being held illegally. Unfortunately for Vallandigham, Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus throughout the United States in September 1862, in an attempt to curb the spying and disinformation campaigns of Southern sympathizers. Vallandigham was one of 15,000 or so civilians detained without trial. In his case, a judge of the federal district court ruled that no civil court was competent to determine whether Vallandigham’s arrest was justified for the government’s self-preservation.

Lincoln, who had a sense of humor as well as a canny political mind, transmuted Vallandigham’s sentence, ordering that he spend the duration of the war in the Confederacy. Writing in June 1863 to the irate Albany Democratic Committee, Lincoln explained:

[H]e who dissuades one man from volunteering, or induces one soldier to desert, weakens the Union cause as much as he who kills a Union soldier in battle. Yet this dissuasion or inducement may be so conducted as to be no defined crime of which any civil court would take cognizance.

Ours is a case of rebellion – so called by the resolutions before me – in fact, a clear, flagrant, and gigantic case of rebellion: and the provision of the Constitution that ‘the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it,’ is the provision which specially applies to our present case. …

[Mr. Vallandigham] was not arrested because he was damaging the political prospects of the Administration, or the personal interests of the Commanding-General, but because he was damaging the army, upon the existence and vigor of which the life of the nation depends. He was warring upon the military, and this gave the military constitutional jurisdiction to lay hands upon him. …

I can no more be persuaded that the Government can constitutionally take no strong measures in time of rebellion, because it can be shown that the same could not be lawfully taken in time of peace, than I can be persuaded that a particular drug is not good medicine for a sick man, because it can be shown not to be good food for a well one. — Lincoln to the Albany Democratic Convention, 1863

Vallandigham promptly fled the South for Niagara Falls. By mid-1864 he had resumed his political life, without any interference from the Lincoln administration.

In the meantime, his case had inspired Edward Everett Hale’s classic 1863 short story, “The Man Without a Country.” The protagonist, Philip Nolan, was enmeshed as a young army lieutenant in Aaron Burr’s traitorous schemes. At his court-martial he petulantly desired never again to hear of the United States. The judge obligingly ordered Nolan’s guards to ensure that he did not. Hale’s narrator offers the story as “a warning to the young Nolans and Vallandighams and Tatnalls of to-day of what it is to throw away a country.”

Vallandigham’s arrest was a cause célèbre at the time, although it turned out to be of negligible consequence to the outcome of the war. But it does raise some fascinating questions that are still worthy of debate. Are there limits to free speech when a country is at war? Do civilians ever fall under military jurisdiction? Can a government established to protect individual rights temporarily abrogate those rights, if the very existence of the government is at stake – if some citizens are attempting to overthrow the government by force, rather than by the means established in the Constitution?

More

- The other Lincoln in the running for best portrait is, of course, Daniel Chester French’s seated sculpture in the Lincoln Memorial, 1920.

- Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886) was born in Leyden, Massachusetts. Among his most notable works are Major General Nathanael Greene, 1867 and Brevet Lt. General Winfield Scott, 1871 (both in Washington, D.C.). Aside from Lincoln, Manhattan has Washington at Union Square, 1856 (Chapter 13). Brooklyn has DeWitt Clinton, ca. 1850 (Green-Wood Cemetery), and another Lincoln, 1866 (Prospect Park – see this post).

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.