I posted my thoughts on the removal of sculptures back in September, as “Politics and Portrait Sculptures.” At around the same time Bill de Blasio formed the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers to consider the possible removal of some New York City sculptures. The Commission has held public hearings, but would not accept any written statement unless the author handed it in at one of the hearings. The Commission was slated to submit its recommendations to Mayor DeBlasio about three months after its formation – so presumably some time in December 2017. An online survey is here.

I couldn’t justify taking time off work to attend a hearing, so I was especially happy when my friend G.A. Mudge headed to the Bronx to submit testimony on November 27, 2017. Mr. Mudge is the author of two books on sculptures in Central Park that are beautifully illustrated with his own photographs: Alice in Central Park: Statues in Wonderland and Two Alice Statues in Central Park. This post is excerpted from the written testimony that he submitted to the Commission. The views and opinions expressed are those of Mr. Mudge, and do not necessarily reflect my own; nor does his appearance on this blog imply that he agrees with all my opinions.

The photos in this post are also by Mr. Mudge. His books on statues in Central Park are available through the above links or directly from Fotobs Books at fotobs@aol.com. Archival prints of his photographs of the statues are available from gamudge@aol.com. See also www.fotobs.com.

From Mr. Mudge:

I have written, photographed, and published two books on the statues in Central Park. My testimony is limited to these monuments. The opinions in this testimony are my own and do not reflect the views of any organization or other person.

The Statues in Central Park

While Angel of the Waters at the Bethesda Terrace is the only statue in the original plan for the park, there are now 60 statues which have emerged without a uniform set of guidelines. The first was dedicated in 1859 to commemorate the centennial birthday of German philosopher Johann C. F. von Schiller. The most recent was dedicated in 2011 to honor Frederick Douglass, a fugitive slave who became an inspirational anti-slavery orator and publisher of abolitionist newspapers. A new monument is being planned – the Woman Suffrage Movement Monument to honor Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and other leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement.

There is remarkable variety in the existing family of statues. For example, there are four military monuments, one statue of a Native American, nine statues of musicians and dancers, nine of poets and writers, two statues of Christopher Columbus and two of Alice from Alice in Wonderland, one statue of a sculptor, one of a doctor, one of a husky, and many more. Four statues celebrate Latin American independence from Spain. This rich variety would not have emerged if one set of guidelines had been in place over the last 160 years. The collection reflects the evolution of values and sensitivities of New Yorkers over time.

Funding for the statues came from a variety of sources – immigrants to honor heroes in the home country, the City of New York, federal grants for relief programs in the Depression, public subscriptions, gifts from foreign governments and cities, and many individuals including small donors and wealthy philanthropists.

Each statue is a combination of fact and fantasy – the fact of bronze or stone in a certain shape and color and the fantasy of the sculptor and of each individual viewer. Each sculptor has exercised artistic license to be both creative and selective in the portrayal of the subject. Each viewer has artistic license to assess and interpret a statue, but not to vandalize it, either physically or by unfair criticism.

To the extent any statue tells a story, that story is not complete; and each statue asks the viewer to step back into history – history of the park, New York City, the United States, art, music, and the world – and to understand and assess the statue as art in the broader historical context.

The Task of the Commission

Part of the task of the Commission is to identify any “symbols of hate” or “offensive” monuments and make recommendations.

The term “symbol of hate” almost defies definition. The terms “target of hate” or “targets of vandalism” may be easier to understand. If a statue is intensely disliked, for whatever reason, perhaps it should be removed, moved, or explained. This said, we must question brief sound bites of hate aimed at any particular statue and try to understand the broad context in which a statue was originally created and dedicated.

Specific Statues

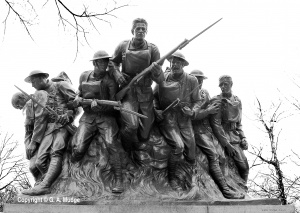

1. 107th Infantry Memorial

This remarkable statue is almost certainly a symbol of the horror, courage, and hate in trench warfare during World War I. Two of seven soldiers are wounded, one severely; two care for the wounded; and three are charging with bayonets drawn. The courage and hate in their faces are unmistakable.

This monument should remain on Fifth Avenue at 67th Street as a memorial to the 107th Infantry, which suffered heavy casualties.

Hate portrayed in a monument does not make the monument per se offensive to require removal.

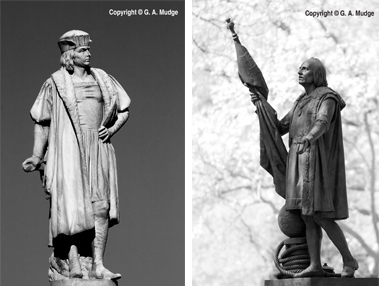

2. Christopher Columbus

There are two statues of Christopher Columbus in Central Park, one at Columbus Circle and one at the south end of the Mall. Both statues commemorate the 400th anniversary of the 1492 landing of Columbus in the West Indies. The statues celebrate the voyage to and the safe landing in the New World.

Neither statue portrays the cruelty, slavery, and torture of indigenous peoples during the subsequent administration by Columbus of colonized territories. These unfortunate aspects of the legacy of Columbus are not honored by either statue.

Neither statue is a symbol of hate or offensive, and both should remain in their current locations. We should recognize and appreciate both statues for what they are and not criticize them for what they are not.

3. James Marion Sims

The statue of Dr. James Marion Sims portrays the doctor standing in the surgical uniform of his day. The statue does not depict the doctor operating on any person. The statue does not display horror or hate in any way. The statue is in good taste by any test of its visible appearance. The statue is not a symbol of hate or offensive as such.

Nevertheless, the statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims is understandably controversial. For example, NYC Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito alleges that Dr. Sims conducted “horrific, painful, medical atrocities on non-anesthetized enslaved Black women with free-reign” and calls for the removal “of this repugnant statue from our neighborhood once and for all.” (emphasis added). In sympathy with the East Harlem community in which the Museum of the City of New York is located, the statement of the Museum acknowledges “that there is a compelling argument to be made for the statue’s removal as a symbol of unethical racist medical practice.” Also in sympathy with the East Harlem community in which The New York Academy of Medicine is located, the letter dated August 25, 2017 from the President of the Academy to Mayor Bill de Blasio objects to “performing surgical experiments on enslaved women without anesthesia and without consent” and further states that public honors should be reserved “for those who have made achievements in health and medicine without infringing on the civil and human rights of others.”

There are two questions:

1. Given these accusations, why was the statue ever permitted by NYC officials to be erected and twice dedicated, first in 1894 in Bryant Park and then in 1934 in its current location on Fifth Avenue opposite The New York Academy of Medicine?

2. What should be done now with the statue?

The answer to the first question can be found in the medical journals. I recommend to all members of the Commission one article in particular titled “The Medical Ethics of Dr. J Marion Sims: A Fresh Look at the Historical Record” by L. Lewis Wall, MD. This article is well researched, well written and balanced. It appeared in the Journal of Medical Ethics in June 2006 and is available here. The introductory abstract of this article states “… the charges that have been made against Sims are largely without merit.” (emphasis added) A complete quotation of the abstract and the conclusion of this article are included after the photograph of the statue. [See More at end of this post.] The entire article merits reflective study by anyone trying to understand the importance of the contributions of Dr. Sims and the controversy around him.

The answer to the first question is simple: Dr. Sims was considered in 1894 and 1934 to be a great doctor by both the medical profession and his patients, and there was no public controversy.

What should be done with the statue now that there is public controversy?

There seem to be five options. Briefly:

1. Maintaining the statue as is in its current location is not a good option. The antipathy of the East Harlem community and its leaders is intense and not likely to abate. The statue is surrounded by a barricade and subject to vandalism. The current situation is not fair to the community, to Dr. Sims, or to the statue and its sculptor.

2. Adding a plaque near the statue in its current location to provide historical context and explanation has been discussed. A plaque would require text that respects and honors both Dr. Sims and the slave women who were his patients and cured by his care. Obtaining agreement on a balanced text may be an insurmountable challenge. Further, a plaque may not be sufficient to dissipate the intense antagonism to the statue.

3. Removing the statue to storage would be a sad result.

4. Moving the statue to a hospital or medical center should be considered. This would require an institution willing to accept and maintain the statue and quite probably adding a plaque near the statue in its new location. A plaque would involve the issues identified above.

5. Moving the statue to a site inside Central Park is a viable option.

This would remove the statue from the hostility of the East Harlem community. Several statues in Central Park have been moved from their original locations, and moving this statue a second time should be possible.

The Woman Suffrage Movement Monument is currently being planned for a location on the Mall. There is room on the Mall just south of this site for another monument – a Woman Health Monument which would consist of two equally important elements:

* The current statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims, and

* Statues honoring Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey, three slaves who were patients of Dr. Sims and whose affliction and cure contributed to the advancement of medicine so important to women.

The current statue is appropriate to honor Dr. Sims, but additional statues are appropriate to honor his slave patients. Without statues that honor the patients, the statue honoring Dr. Sims does not by itself tell the story of the important medical advances made together by the doctor and his patients.

Thank you.

G.A. Mudge

More

- My essay “Politics and Portrait Sculptures” is available as a printable PDF: feel free to share! Guest posts on this subject: Zenos Frudakis and Quent Cordair, Francis Morrone.

- The report of the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers is available at www1.nyc.gov/assets/

monuments/downloads/pdf/mac- monuments-report.pdf (Mr. Mudge’s full testimony is available at page 5 of the link to the public testimony available on page 39 of the Report.) - The abstract of L. Lewis Wall’s article “The Medical Ethics of Dr. J. Marion Sims: A Fresh Look at the Historical Record,” published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, June 2006:

Vesicovaginal fistula was a catastrophic complication of childbirth among 19th century American women. The first consistently successful operation for this condition was developed by Dr J Marion Sims, an Alabama surgeon who carried out a series of experimental operations on black slave women between 1845 and 1849. Numerous modern authors have attacked Sims‘s medical ethics, arguing that he manipulated the institution of slavery to perform ethically unacceptable human experiments on powerless, unconsenting women. This article reviews these allegations using primary historical source material and concludes that the charges that have been made against Sims are largely without merit. Sims‘s modern critics have discounted the enormous suffering experienced by fistula victims, have ignored the controversies that surrounded the introduction of anaesthesia into surgical practice in the middle of the 19th century, and have consistently misrepresented the historical record in their attacks on Sims. Although enslaved African American women certainly represented a “vulnerable population” in the 19th century American South, the evidence suggests that Sims‘s original patients were willing participants in his surgical attempts to cure their affliction-a condition for which no other viable therapy existed at that time.

- Lewis’s conclusion, in its entirety:

It is difficult to make fair assessments of the medical ethics of past practitioners from a distant vantage point in a society that has moved in a different direction, developed different values, and has wrestled—often unsuccessfully—with ethical issues of sex, race, gender, and class that were not perceived as problematic by those who lived during an earlier period of history. J Marion Sims was a dedicated and conscientious physician who lived and worked in a slaveholding society. As such, he was often called upon to care for slaves with legitimate medical needs. Among the needs that many 19th century women faced—both white and black—was the need for treatment of catastrophic complications of childbirth such as vesicovaginal fistulas. The operations carried out by Sims on black slave women from 1845–1849 represented his attempt to cure them of an odious and devastating condition that was then considered incurable. His operations, which at first were unsuccessful, were performed explicitly for therapeutic purposes and, as far as we can tell from the surviving sources, were carried out with the patients’ cooperation and consent. At the time Sims began his efforts to close vesicovaginal fistulas, there was no effective alternative to surgical treatment and the quality of life to which such patients were reduced by their injuries was acknowledged by all medical writers of the time as unendurable. There is no doubt that slaves in the mid‐19th century American South were a “vulnerable” population who were often subjected to significant abuse by the slaveholding system. To suggest, however, that for that reason alone no attempts should have been made to cure the maladies of such enslaved women, especially when they were desperate for help and no other viable alternatives existed, seems ethically bankrupt itself. Whatever his other failings may have been, J Marion Sims pursued this clinical goal with vigour, determination, and perseverance, and both his patients then and countless thousands of women since, benefited from his success.

More

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.