Part 2: My Analysis of the Puritan

Before you dive into this, why not have a closer look at the Puritan on your own, with the questions in last week’s post? Then you’ll have the fun of violently agreeing or disagreeing with me. If you want to look at the sculpture in 3-D, there’s a list of locations of copies of the work at the end of that post.

First Impressions

The first thing that strikes me about the Puritan is the overwhelming size of the figure: it’s tall as well as broad. It stands over eight and a half feet tall, and on its present site in Springfield is raised even higher by a round, stepped pedestal.

I know that some figures are large so they can be seen from a distance: the Statue of Liberty, for example. Others are large as a celebration of the over-life-size grandeur of the figure represented: Washington at Union Square comes to mind. Sometimes the size is simply attention-grabbing, the visual equivalent of shouting “Pay attention! This is important.” At this point I’m not sure why this particular figure is so large. Perhaps after I look closely at the details, it will become obvious.

Subject

The person represented is a Puritan: he’s immediately recognizable because of his hat, which appears in Thanksgiving decorations and on signs up and down the Massachusetts Turnpike. For more on how this costume came to be accepted as the standard Puritan outfit, see Part 3: Historical Notes (next week).

Objects

Contrasting the Puritan with MacMonnies’s Nathan Hale makes clearer to me the effect of many of Saint Gaudens’s choices in this work.

Hale is tall and slender. The Puritan is tall, but much more solidly built than Hale. Looking from the side, I can see that his back is very straight, which suggests energy and confidence. The position of the Puritan’s arms makes him appear even broader, because the cape flares over them, away from his figure. This is especially noticeable when looking at his back. (Alas, I have no photo of that.)

The Puritan faces front and has one foot far forward, so he seems to be taking long strides toward me, not just strolling along. His motion is energetic and purposeful.

The facial feature immediately noticeable is his mouth, held firmly closed in a long, thin line. The deep lines bracketing the mouth suggest that the man represented is at least fifty years old: it takes decades to develop such deep lines. The combination of the lines and the way he holds his mouth suggest that he’s perpetually in a grim mood.

Usually the most expressive feature of a face is the eyes, but the Puritan’s eyes are difficult to see in the shadow beneath his hat brim. After spending hours trying to see his eyes in photos and, later, when standing in front of this sculpture in Springfield, I had a revelation. If I can’t see a detail despite my best efforts, then either the artist did not emphasize it (hence it’s insignificant), or the artist did not want me to see that detail—he wanted to leave it ambiguous or mysterious. In this case, the expression in the Puritan’s eyes is less important than the grim mouth and the size and the movement of his body. Besides that, the fact that I can’t see his eyes makes him remote, perhaps even slightly sinister. It’s much easier to read someone’s intentions if I can see their eyes.

Nathan Hale’s hair is tousled, adding to the impression that he’s suffered rough treatment. The hair under the Puritan‘s hat seems to be cut short: it’s visible from the side only. Perhaps this suggests the type of person who has an aversion to making himself attractive: I’ll have to see if there’s other evidence for that.

What can I say about this figure so far? He’s a man in his fifties or sixties, tall and solidly built, who holds himself with confidence and moves forward with energy. He’s coming straight at me. His mouth is grim, his eyes hidden. To combine those observations into a statement that I can remember while looking at the rest of the sculpture’s details, I’ll need to figure out which characteristics are more important, and then subordinate or omit the others. My first attempt is: “A grim, stalwart Puritan strides toward the viewer.”

What can I learn from looking at the Puritan’s costume? The items he and Hale wear are basically the same: shirt, vest, trousers, hose, shoes. But what a difference in the details! Nathan Hale wears a shirt, pants, and vest that fit snugly, so I can see the young, slender body beneath. The Puritan is covered in heavy, loose clothing up to his chin and down to his wrists and toes.

His long vest seems to be made of stiff material that stands out from his body. Beneath it I can’t see any details of his torso, although it’s clear he’s sturdily built. The Puritan’s vest has twenty-two buttons, twelve of which are fastened, compared to Hale’s three. Surely these are too many buttons merely for keeping the vest closed: phrases like “buttoned up tight” and “straitlaced” come to mind. His shirt is fastened all the way to his chin, concealing his neck. Given all this, his short hair probably is another sign that he disapproves of personal adornment.

The hat’s high crown makes him appear even taller. The collar of the cape, reaching well above his chin, combines with the hat’s wide brim to throw his face into shadow and further obscure his features.

The folds of the heavy cape (it hangs nearly straight, even though the Puritan seems to be walking briskly) reach to his ankles, making him as broad as he is tall—as I noticed when looking at the position of his arms. The cape also makes it more difficult to see his body, which is already muffled under the heavy clothing.

The Puritan’s pants are baggy: I can’t see much of his legs. Thick ribbed hose obscure his calves. His shoes are large and ungainly, in comparison to the elegant footwear of Houdon’s Washington. They, too, obscure his anatomy.

What’s the point of this enveloping clothing? It reminds me, vividly and visually, that the Puritans did not approve of vanity, or even of letting others see one’s body.

In his right hand the Puritan grasps a thick, gnarled staff. Compared to the cane on which Houdon’s Washington casually leans, the Puritan’s staff looks rough-hewn, perhaps a reminder of a time when Americans focused on survival rather than elegance. But the staff also looks as if it could be a weapon—a cudgel. Given how stalwart and energetic our Puritan is, he certainly doesn’t seem to need the staff for support. Also, last time I twisted an ankle, I learned that if one uses a cane for support, one places it near the weak foot, not far out to the side. The Puritan appears to be using his staff not for support, but to cut an even wider swath than his cape and his bulk require.

In his left arm the Puritan holds a huge book – it’s the length of his leg from knee to ankle. Although its edges face forward so I can’t see the title, the only book of this size that a Puritan would be likely to carry is the Bible.

I recalled that Renaissance artists often showed the Four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) carrying Bibles, so I quickly Googled “Donatello St. Mark” and found that the Bible held by Donatello’s St. Mark is much smaller—not even the length of St. Mark’s forearm. Our Puritan’s huge Bible could almost be a shield—a defense against all comers—or even a battering ram. Hmmm, and I said the staff looked like a cudgel. What a militant figure he seems to be! “Onward, Christian soldiers, marching as to war …”

On the other hand, the way the Puritan carries his huge Bible also reminds me of images of Moses carrying the Ten Commandments, which calls to mind God-given authority and the rescue (with or without their consent) of those who have strayed from the path of righteousness. Saint Gaudens might well have had both these associations (soldiers and Moses) in mind when he sculpted the Puritan. The manner in which the Puritan carries his staff and Bible convince me that this is a figure of authority, somewhere between militant and menacing.

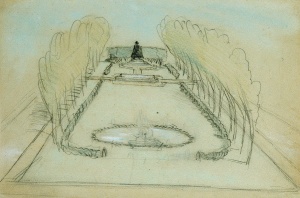

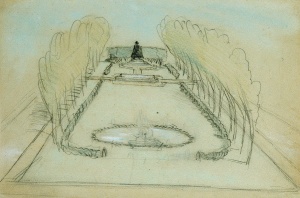

From reading about Saint Gaudens, I know that the original setting for the Puritan was designed by architect Stanford White, a friend of Saint Gaudens. That setting (in Stearns Park, Springfield) made the Puritan appear even more overwhelming. The over-life-size sculpture stood on a pedestal about six feet high and seventeen feet in diameter: the figure was not easily approachable, and in a very literal sense was looking down on visitors. The park in which the sculpture stood was a long, narrow rectangle. High hedges or trees blocked off the view to either side. The Puritan stood at the far end, with a hedge behind him that thwarted escape. In that context, the Puritan must have seemed to be advancing inexorably on the viewer, forcing him to give in or retreat. Alas, that effect is now lost. The Puritan presently stands on a small knoll in wide-open Merrick Park. But the high pedestal on a hill still lets it loom.

Earlier I proposed as a statement of the sculpture’s message: “A grim, stalwart Puritan strides toward the viewer.” From studying his clothing, staff, and Bible, and from imagining the effect of the original setting, I’ve added the idea that he is a menacing, militant figure, and that he’s enveloped in his clothing. The disapproval of showing almost any aspect of the human body is pretty much covered by the term “puritanical,” so perhaps I need not mention that specifically.

At this point I can say, in answer to my question under “First Impressions,” that this figure’s size is intended to intimidate: it looms, in fact. I revise my statement to include that: “A grim, looming Puritan armed with staff and Bible strides inexorably toward the viewer.” I could have simply said “militant,” but “armed with staff and Bible” is more evocative of this particular sculpture. If the figure could talk, he might say, “One way or another, I’ll make you believe.”

More

- Next week: the conclusion of my analysis and interpretation, and the historical context of this work.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.