According to eyewitness accounts of the British surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, the British were valiant enemies, cowardly, and drunk; the Americans were ragged, brave, and snide; and the French … well, according to every single source, the French were beautifully dressed. Ça va sans dire. (Note: my two earlier posts on Yorktown are here and here.)

According to eyewitness accounts of the British surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, the British were valiant enemies, cowardly, and drunk; the Americans were ragged, brave, and snide; and the French … well, according to every single source, the French were beautifully dressed. Ça va sans dire. (Note: my two earlier posts on Yorktown are here and here.)

October 19: “The British army which so lately spread dismay and desolation … disrobed of all their terrors”

Events of the day:

- In the morning, Washington sent the Articles of Capitulation to Cornwallis, with the requirement that he sign by 11 a.m. Why the rush? There was still a chance that the British fleet would sail into Chesapeake Bay at any moment: Washington did not allow Cornwallis to stall. Washington signed the Articles soon after Cornwallis.

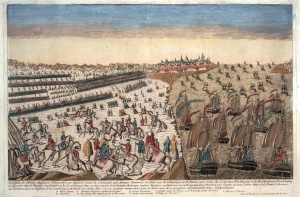

- At 2 p.m., the British marched half or three-quarters of a mile, through a double file of French and American troops, to a field outside Yorktown. There they surrendered their weapons, then marched back into Yorktown. Cornwallis, claiming sickness, sent General Charles O’Hara to preside over the surrender.

Third of the Articles of Capitulation:

The garrison of York will march out to a place to be appointed in front of the posts, at two o’clock precisely, with shouldered arms, colours cased, and drums beating a British or German march. They are then to ground their arms, and return to their encampments, where they will remain until they are dispatched to the places of their destination. (More here; on the honors of war, see last week’s post)

Corporal Stephan Popp (German in British service):

The terms of surrender were finally agreed on. … Everything was done in a regular military way. We were heartily glad the siege was over, for we all thought there would be another attack … During the siege the enemy had fired more than 8000 great bombs, of from 100 to 150 and 200 pounds. On the day of the surrender Corporal Popp was promoted to Lieutenant. …

Of munitions of war there were left only 23 kegs of powder.

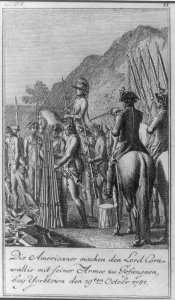

At 3-4 p.m. all of Lord Cornwallis’ troops, with all our personal effects and our side arms, colors covered, marched out of our lines on the Williamsburg road, between the Regiments of the enemy, which were all drawn up, with colors flying and bands playing, – our drums beating, – the French were on our right in parade, their General at the head, – fine looking young fellows the soldiers were, – on our left the Americans, mostly regular, but the Virginia militia too, – but to look on them and on the others was like day and night.

We were astonished at the great force and we were only a Corporal’s Guard compared to their overwhelming numbers. They were well supplied and equipped in every way. (Popp’s Journal, 1777-1783)

Johann Doelha (German in British service):

In the afternoon of the 19th of October, between 3 and 4 o’clock all the troops marched out of the lines and camp with bag and baggage, muskets and side arms, with standards cased, but with drums and fifes playing. Brigadier General O’Hara led us out and surrendered us …

On the right flank, every regiment of the French paraded white silk colors adorned with 3 silver lilies; beyond the colors stood drummers and fifers and in front of the colors the Haubisten [band] which made splendid music. In general the French troops appeared very well, they were good looking, tall, well-washed men … To our left as we marched out, or on the left flank, stood the American troops drawn up on parade with their generals, Washington, Gates, Green and Wayne. They stood in 3 ranks, first the regular troops which also had Haubisten and msuicians making beautiful music and appeared tolerable enough. After them were the militia from Virginia and Maryland who looked rather badly tattered and worn.

We, now prisoners, saw all these troops standing 3 ranks deep in a line over an English miles long, with wonder and great astonishment at the great multitude, which had besieged us. One saw, indeed, that they could have devoured us who were only a corporal’s guard compared with them. The lines of both armies were drawn out nearly 2 English miles. One can imagine that an army of more than 40,000 men, also when it is paraded in 2 lines 3 ranks deep, requires space. [NOTE: The combined American and French forces totaled at most some 19,000.] The enemy was much amazed at our small force as we marched out as they had supposed us numerous. …

As everything was now over, we marched back through the two armies – but in silence – into our lines and camp, having nothing more than our few effects in the packs on our backs. All spirit and courage which at other times animated the soldiers had slipped from us, especially inasmuch as the Americans greatly jeered at us like conquerors as we marched back through the armies. (“The Doehla Journal,” translated by Robert J. Tilden, William and Mary Quarterly 2nd series, 22:3 [July 1942], p. 257-9)

James Thacher (American):

This is to us a most glorious day; but to the English, one of bitter chagrin and disappointment. Preparations are now making to receive as captives that vindictive, haughty commander, and that victorious army, who, by their robberies and murders, have so long been a scourge to our brethren of the Southern states. Being on horseback, I anticipate a full share of satisfaction in viewing the various movements in the interesting scene …

The royal troops, while marching through the line formed by the allied army, exhibited a decent and neat appearance, as respects arms and clothing, for their commander opened his store, and directed every soldier to be furnished with a new suit complete, prior to the capitulation. But in their line of march we remarked a disorderly and unsoldierly conduct, their step was irregular, and their ranks frequently broken. (More here)

Lt. William Feltman (American):

The British army marched out and grounded their arms in front of our line. Our whole army drew up for them to march through, the French army on their right and the American army on their left. The British prisoners all appeared to be much in liquor. (More here)

Baron Ludwig von Closen (German in French service):

In passing between the two armies, they showed the greatest scorn for the Americans, who, to tell the truth, were eclipsed by our army in splendor of appearance and dress, for most of these unfortunate persons were clad in small jackets of white cloth, dirty and ragged, and a number of them were almost barefoot. The English had given them the nickname of Yankee Doodle. What does it matter! an intelligent man would say. These people are much more praise-worthy and brave to fight as they do, when they are so poorly supplied with everything. (The Revolutionary War Journal of Baron Ludwig von Closen 1780-1783, trans. & ed. Evelyn M. Acomb)

Lt.-Col. Saint George Tucker (American):

This Morning at nine oClock the Articles of Capitulation were signed and exchanged—At retreat beating last night the British play’d the Tune of “Welcome Brother Debtor”—to their conquerors the tune was by no means dissagreeable— …

Our Army was drawn up in a Line on each side of the road … the Americans on the right, the French on the left. Thro’ these Lines the whole British Army march’d their Drums in Front beating a slow March. Their Colours furl’d and Cased. I am told they were restricted by the capitulation from beating a French or American march. General Lincoln with his Aids conducted them—Having passed thro’ our whole Army they grounded their Arms & march’d back again thro’ the Army a second Time into the Town—The sight was too pleasing to an American to admit of Description— (More here)

Lt.-Col. Henry Lee (American):

Valiant troops yielding up their arms after fighting in defence of a cause dear to them (because the cause of their country), under a leader who, throughout the war, in every grade and in every situation to which he had been called, appeared the Hector of his host. Battle after battle had he fought; climate after climate had he endured; towns had yielded to his mandate, posts were abandoned at his approach; armies were con quered by his prowess; one nearly exterminated, another chased from the confines of South Carolina beyond the Dan into Virginia, and a third severely chastised in that State on the shores of James River. But here even he, in the midst of his splendid career, found his conqueror.

The road through which they marched was lined with spectators, French and American. On one side the commander-in-chief, surrounded by his suite and the American staff, took his station; on the other side, opposite to him, was the Count de Rochambeau, in like manner attended. The captive army approached, moving slowly in column with grace and precision. Universal silence was observed amid the vast concourse, and the utmost decency prevailed: exhibiting in demeanor an awful sense of the vicissitudes of human life, mingled with commiseration for the unhappy. The head of the column approached the commander-in-chief; O’Hara, mistaking the circle, turned to that on his left, for the purpose of paying his respects to the commander-in-chief, and requesting further orders; when, quickly discovering his error, with much embarrassment in his countenance he flew across the road, and, advancing up to Washington, asked pardon for his mistake, apologized for the absence of Lord Cornwallis, and begged to know his further pleasure. The General, feeling his embarrassment, relieved it by referring him with much politeness to General Lincoln …

Every eye was turned, searching for the British commander-in-chief, anxious to look at that man, heretofore so much the object of their dread. All were disappointed. Cornwallis held himself back from the humiliating scene; obeying sensations which his great character ought to have stifled. He had been unfortunate, not from any false step or deficiency of exertion on his part, but from the infatuated policy of his superior [General Henry Clinton], and the united power of his enemy, brought to bear upon him alone. There was nothing with which he could reproach himself ; there was nothing with which he could reproach his brave and faithful army: why not, then, appear at its head in the day of misfortune, as he had always done in the day of triumph? The British general in this instance deviated from his usual line of conduct, dimming the splendor of his long and brilliant career. (From Johnston, pp. 176-177)

Colonel Fontaine (American):

I had the happiness to see that British army which so lately spread dismay and desolation through all our country, march forth on the 20th inst. [19th] at 3 o’clock through our whole army, drawn up in two lines about 20 yards distance and return disrobed of all their terrors, so humbled and so struck at the appearance of our troops, that their knees seemed to tremble, and you could not see a platoon that marched in any order. Such a noble figure did our array make, that I scarce know which drew my attention most. You could not have heard a whisper or seen the least motion throughout our whole line, but every countenance was erect, and expressed a serene cheerfulness. Cornwallis pretended to be ill, and imposed the mortifying duty of leading forth the captives on Gen. O’Hara. Their own officers acknowledge them to be the flower of the British troops, but I do not think they at all exceeded in appearance our own or the French. The latter, you may be assured, are very different from the ideas formerly inculcated in us of a people living on frogs and coarse vegetables. Finer troops I never saw. His Lordship’s defence I think was rather feeble. His surrender was eight or ten days sooner than the most sanguine expected, though his force and resources were much greater than we conceived. (Quoted in Johnston, pp. 177-8)

Lt. Ebenezer Denny (American):

The British army parade and march out with their colors furled; drums beat as if they did not care how. Grounded their arms and returned to town. Much confusion and riot among the British through the day; many of the soldiers were intoxicated; several attempts in course of the night to break open stores; an American sentinel killed by a British soldier with a bayonet; our patrols kept busy. Glad to be relieved from this disagreeable station. Negroes lie about, sick and dying, in every stage of the small pox. Never was in so filthy a place – some handsome houses, but prodigiously shattered. Vast heaps of shot and shells lying about in every quarter, which came from our works. The shells did not burst, as was expected. Returns of British soldiers, prisoners six thousand, and seamen about one thousand. (More here)

Sergeant Joseph Plumb Martin (American):

The next day we were ordered to put ourselves in as good order as our circumstances would admit, to see (what was the completion of our present wishes) the British army march out and stack their arms. The trenches, where they crossed the road leading to the town, were leveled and all things put in order for this grand exhibition. After breakfast, on the nineteenth, we were marched onto the ground and paraded on the right-hand side of the road, and the French forces on the left. We waited two or three hours before the British made their appearance. They were not always so dilatory, but they were compelled at last, by necessity, to appear, all armed, with bayonets fixed, drums beating, and faces lengthening. They were led by General [Charles] O’Hara, with the American General Lincoln on his right, the Americans and French beating a march as they passed out between them. It was a noble sight to us, and the more so, as it seemed to promise a speedy conclusion to the contest. The British did not make so good an appearance as the German forces, but there was certainly some allowance to be made in their favor. The English felt their honor wounded, the Germans did not greatly care whose hands they were in. The British paid the Americans, seemingly, but little attention as they passed them, but they eyed the French with considerable malice depicted in their countenances. (More here)

Sara Osborn, wife of an American soldier (“deponent” in the selection below):

Deponent stood on one side of the road and the American officers upon the other side when the British officers came out of the town and rode up to the American officers and delivered up [their swords, which the deponent] thinks were returned again, and the British officers rode right on before the army, who marched out beating and playing a melancholy tune, their drums covered with black handkerchiefs and their fifes with black ribbands tied around them, into an old field and there grounded their arms and then returned into town again to await their destiny. Deponent recollects seeing a great many American officers, some on horseback and some on foot, but cannot call them all by name. (More here; on covering the drums and tying ribands on the fifes, see the More heading below)

Colonel Daniel Trabue (American):

The news [of the surrender] went far and near, and a vast number of people from Different towns and the country came forward to see the great and mighty sight.

The British had a very large gate in the South side of their fort, and on that side was a level old field. Our army was placed in a solid square column about half a mile or more around the fort gate ; it was a great sight. Part of our line was Continental Troops, part was Militia, and part was French. On the out-side of this column of soldiery was a vast number of spectators, mostly in carriages such as chariots, Fayatons, chairs, and gigs, also some common wagons. The carriages were full of gentlemen, ladies and children, besides a number on horse-back, and some on foot. Some had come as far as the city of Richmond, which was upwards of 70 miles. There were many thousands of these spectators.

General Washington and some of the officers with their aids were about the center of this vast column, immediately before the gate, and about 1/2 or 3/4 of a mile Distant. About the middle of the Day the big gate opened, and the red Coats marched out by Platoons in a solid column with some of their Officers. Our Officers, soldiers and spectators said “Did you ever see the like,” and many words were spoken but not loud.

It was the most Tremendous and most admirable Sight that I ever saw. The countenances of our Officers, and soldiers all seemed to claim some credit for the great prize; and the countenances of the spectators seemed to say, also, that they deserved credit. It was truly a wonderful sight to see so many British coming out in their red coats to ground their arms. They marched straight up to General Washington, and gave up their swords and ground their arms or stacked them, and then returned to the Fort. …

That night I noticed that the officers and soldiers could scarcely talk for laughing, and they could scarcely walk for jumping and Dancing and singing as they went about. …

The Continental Officers and soldiers guarded the Gates of the Fort, and none of the militia were allowed to go in the Fort; one reason was the small-pox was bad there. I had a relative who was a Continental Officer. He was Lieutenant John Trabue; the very next day I went with him all over the Fort. It seemed to be nearly one mile in length by 1/4 mile in width. It was truly a Dreadfully shocking sight to see the damage our bomb-shells had Done. When a shell fell on the ground it would sink under the ground so Deep that when it burst it would throw up a wagon load, or even more of Dirt; and when it fell on a house it Tore it to pieces. The British had a number of holes and Pits Dug all over the Fort, some large and some small with timber in the top edge; when the soldiers would see a shell coming near them they could jump in one of the pits and squat Down until it had burst.

They had some large holes under ground [i.e., caves] where Lord Cornwallis, and some of the nobles staid. They called them bomb-proof, but with all their caution a vast number of them were killed.

I have been told by some of the soldiers since, that there was always some one on the watch. They could see a shell coming, and at times there was Dreadful scampering, and sometimes they would come so often, they were much beset. Mr. Jacob Phillip told me a while before they surrendered they lost 40 men every hour. They threw a number of their arms and cannon in the Deep water.

When a shell would fall on any hard place, so that it would not go under the ground, a soldier would go to it and knock off the fiz, or neck, and then it would not burst. The soldier then received a shilling for that act. They said they did not care much about their life, but that the shilling would buy spirits! ...

The British Officers and Tories looked much dejected, and they had sad countenances, as I saw them passing I hardly heard them say a word. I thought the English soldiers, and Hessians Did not seem to Care much about it.

Everything in the Fort looked gloomy and sad. Lord Cornwallis and his other Officers looked not only sad, but ashamed. They had lived under the ground like ground Hogs [i.e., in caves]. The negroes looked condemned, for the British had promised them their freedom, but instead of freedom they made them haul wagons, by hand, with timber to build their works, and made them work very hard with spades.

I left their Fort and went to our army, and what a Great Contrast our men presented. They were pert and lively, and still rejoicing. … (More here)

Washington to Thomas McKean, President of the Continental Congress:

I have the Honor to inform Congress, that a Reduction of the British Army under the Command of Lord Cornwallis, is most happily effected—The unremitting Ardor which actuated every Officer & Soldier in the combined Army on this Occasion, has principally led to this Important Event, at an earlier period than my most sanguine Hopes had induced me to expect. … (More here)

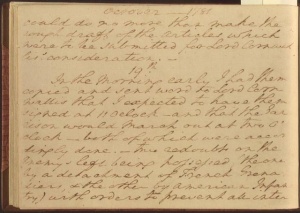

Commander-in-Chief George Washington’s diary entry for October 19, 1781. Just the facts, ma’am. Damn, I love GW.

In the morning early I had [the Articles of Capitulation] copied and sent word to Lord Cornwallis that I expected to have them signed at 11 o’clock, and that the garrison would march out at two o’clock, both of which were accordingly done, the redoubts on the enemy’s left being possessed, the one by a detachment of French Grenadiers, & the other by American Infantry with orders to prevent an intercourse between the army & country and the town, while officers in the several departments were employed in taking acct. of the public stores &c.

October 20: The final tally

Events of the day:

- In accordance with the Articles of Capitulation, the sloop Bonetta sailed for New York, carrying Cornwallis’s report to Clinton and as many loyalists and soldiers as it could hold.

- Casualties at Yorktown: on the American and French side, fewer than 100 killed, about 300 wounded; on the British side, 200-300 killed, 300-600 wounded. About 7,500 British and their German auxiliaries were taken prisoner.

- Among the articles surrendered: 82 ships (mostly small); 191 cannon, mortars, and howitzers; 2,749 cannon balls; 693 bombs, grenades, and canister shot; 23 kegs of powder, each 120 lbs. (but considerably more was lost in the explosion of a powder magazine the night of the 18th).

October 24: The British fleet arrives from New York

The British fleet, which had departed New York harbor on the 19th, arrived off the coast of Virginia after five days at sea. Near Chesapeake Bay it met a small ship whose passengers and crew informed General Clinton that Cornwallis had surrendered on the 19th. The fleet cruised the area for five days seeking confirmation, then sailed back to New York on October 29.

All the details of the operation were hardly concluded when the strong English squadron of twenty-seven sail, including the three of fifty [guns], appeared off Cape Henry on the twenty-seventh. It had on board a corps of troops under the joint command of General Clinton and Prince Frederick Henry [NOTE: actually Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, King George III’s younger brother]. After making sure that the aid they carried was useless, they stood out to sea. The fleet of M. de Grasse left on November 4 … (Rochambeau, “Memoire de la Guerre en Amerique,” ed. Claude C. Sturgill, The Virginia Magazine of History & Biography 78:1, part 1 (Jan. 1970), p. 63)

November 25: “Oh God! it is all over!”

News of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown arrived in London on November 25, 1781. Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall described the effect of the news on Lord North, Britain’s prime minister:

The First Minister’s firmness and even his presence of mind gave way for a time under this awful disaster. I asked Lord George afterward how he took the communication when made to him ? “As he would have taken a ball in his breast,” replied Lord George. For he opened his arms exclaiming wildly as he paced up and down the apartment, during a few minutes, “Oh God ! it is all over !” Words which he repeated many times, under emotions of the deepest agitation and distress. (Quoted in Johnston, pp. 179-180)

Eyewitness accounts of Yorktown

Thanks to Michael Newton, author of Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, for helping me expand my list of sources. If you know of others, email me at DuranteDianne@gmail.com.

Journals (written at the time of the siege)

- Denny, Lt. Ebenezer (American): Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny

- Doehla, Johann (German in British service): “The Doehla Journal,” translated by Robert J. Tilden, William and Mary Quarterly, 2nd series, 22:3 (July 1942), pp. 229-274

- Feltman, Lt. William (American): The Journal of Lieut. William Feltman, of the First Pennsylvania Regiment

- Popp, Col. Stephan (German in British service): Popp’s Journal, 1777-1783

- Thacher, James (American surgeon): Military Journal of the American Revolution

- Tucker, Lt-Col. St. George (American): “Journal of the Siege of Yorktown”

Letters

- Cornwallis, General Charles (British): letters to Commander-in-Chief Henry Clinton, reprinted in Tarleton’s A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781

- Hamilton, Lt. Col. Alexander (American): letter to Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton of October 12, report written October 15 regarding the attack on Redoubt 10, and letter to Elizabeth on October 18

- Washington, George (American): search the Founders Archive for letters written in September and October 1781

Narratives written an indefinite time later

- Fontaine, Col. (American): quoted in Henry Phelps Johnston, The Yorktown Campaign and the Surrender of Cornwallis, 1781 (Philadelphia, 1881)

- Lafayette, Marquis de (French): Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts of General Lafayette

- Lee, Lt.-Col. Henry (American): quoted in Johnston, The Yorktown Campaign and the Surrender of Cornwallis, 1781

- Martin, Sergeant Joseph Plumb (American): section of his narrative on Yorktown

- Osborn, Sarah (American, wife of a soldier): deposition filed in 1837

- Rochambeau, Comte / Admiral (French): “Memoire de la Guerre en Amerique,” ed. Claude C. Sturgill, The Virginia Magazine of History & Biography 78:1, part 1 (Jan. 1970), p. 63)

- Tarleton, Lt.-General Banastre (British): A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781

- Trabue, Col. Daniel (American): Colonial Men and Times, containing the Journal of Col. Daniel Trabue

More

- I wondered about Sara Osborn’s account of black-draped drums and fifes with black ribands. SFC Jay Martin of the United States Army Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps kindly replied to my query:

Her account comes from her submission for a pension. Individuals who did not have an official record of service to verify their service were required to provide a detailed account of their activities/contributions to the war. The obvious issue with these narrative accounts is that they were given decades after the fact and are subject to false, embellished or tainted (by stories heard or read in the interim) recollections.

Several other accounts address the marching out of the British troops to the sound of drums. The others that I have read do not mention the drums being covered. One description that comes up a couple of times is the drums playing a ‘slow march’. This would be a slow, understated march / rhythm typical of a somber occasion like a funeral. But her account is the only one I have read that describes the drums being covered.

Covering drums in black cloth for funeral processions was certainly done in that era and is still sometimes done today.

So, as far as 100% accuracy as you know, we cannot say. But, as you asked is it possible, certainly.Having said that, I’m sure there is a history buff or two out there who will tell you absolutely not because it was not specified in “X” or “Y” manuals. In reality, just like today, commanders and troops exercised a certain amount of discretion or improvisation in the moment.

In short, if one was trying to represent the event with as much accuracy as possible, I would stay away from covering the drums because we don’t know. If one was trying to add to the drama, or weight of the scene being depicted, I feel covering the drums in black would certainly fall with in very reasonable artistic license.

- Did you notice that I didn’t mention the British playing “The World Turned Upside Down?” Clever you. More on that next week.

- I’ve started adding comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical: a fantastic resource. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the thirty-seventh in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. My intro to this series is here. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.