In 2022, I emailed 158 art-related items to my members of my free Sunday Recommendations list. For supporters, I recommended 52 more items. This week: my favorites in the categories of painting and sculpture. Eight of these were originally shared only with supporters: those are marked with a pair of asterisks.

This post is available as a video at https://youtu.be/CC3otefRj8Y.

Painting

TIED FOR FIRST:

- **Michelangelo. Sistine Ceiling (1508-1512). When I visited the Sistine Chapel years ago, I was part of a group tour, and was hustled out of the room long before I could finish squinting up at the ceiling. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition includes nearly every part of the Sistine painted by Michelangelo, via high-definition, life-size photos displayed at floor level. (Exception: the Last Judgment is smaller than the original, and the ignudi are mostly missing.) Size does matter: seeing these at full-scale is very different from seeing them in a coffee-table book or on a computer monitor. The exhibition is touring the US well into 2023: details here. If you walk through it with the audio guide, it’ll take at least 2 hours. People often talk with awe about Michelangelo’s muscular bodies, but I was most impressed by the variety of ages and expressions on the faces. This is a collage of photos I took of photos that someone else took.

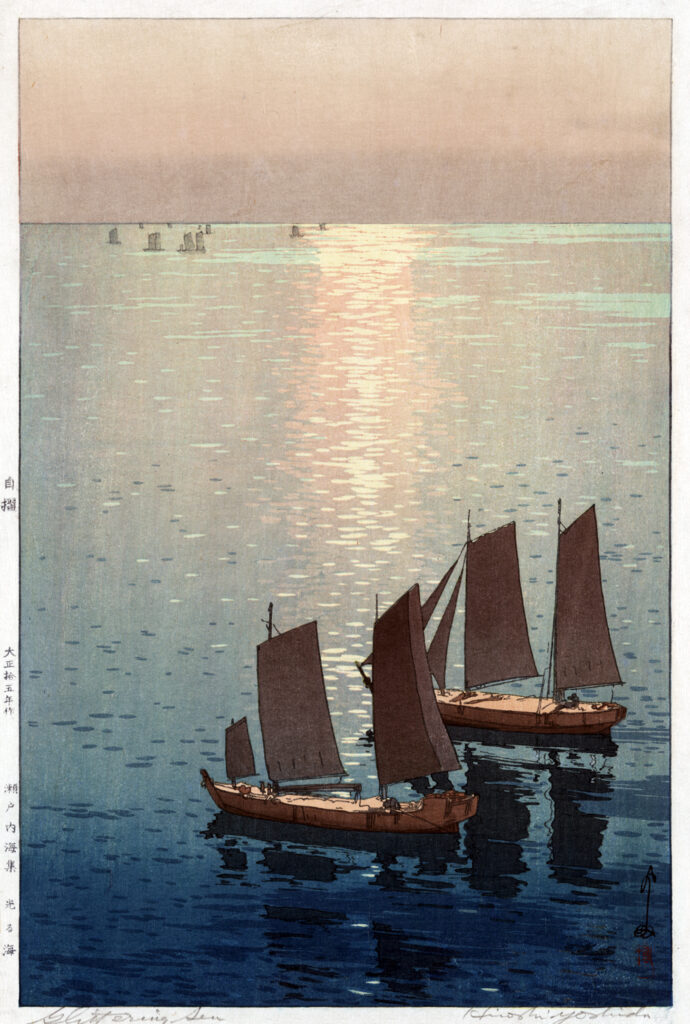

- **Yoshida, Hiroshi (1876-1950). The Sparkling Sea (1926). In the mid-nineteenth century, ukiyo-e woodblock prints became popular in the West, with subjects such as beautiful women, actors, wrestlers, folk tales, and historical scenes. Such prints fell out of fashion in the early 1900s. But beginning in 1915, Watanabe Shozaburo single-handedly created a revival of woodblock prints by publishing and selling a new style known as shin-hanga. Shin-hanga prints feature a fusion of Japanese and Western art, with natural subjects such as birds, animals, flowers, and landscapes. As many as 20 separate blocks may be cut to add colors for each print. Yoshida, one of the greatest artists of the shin-hanga style, is famous for landscapes and for seascapes such as this one. More on Yoshida here; more examples of shin-hanga here. Many of these prints are available for sale, from a couple hundred to a couple thousand dollars each.

RUNNERS UP

- **Armstrong, Rolf. Self Portrait (1914). Armstrong (1889-1960) studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and at the Académie Julian in Paris, then began focusing on paintings of glamorous women for magazine covers. (This was the Golden Age of American Illustration: see my comments on Maxfield Parrish’s early career in Artist-Entrepreneurs.) From 1912 through 1936, Armstrong created about 200 cover illustrations, including many of silent-screen actors. In the 1920s and 1930s, as color photography replaced illustrations on magazine covers, Armstrong began to create calendar art and advertisements, among them some of the most reproduced art of World War II. The New York Times dubbed him “creator of the calendar girl”. His self-portrait is striking: look at the way the light models his face. My favorite among the dozens of his works I’ve seen is a skier from 1934, apparently created for an ad.

- Metcalf, Willard (1858-1925) On the Suffolk Coast (private collection) (1885). Metcalf was a member of the Cornish Colony, which formed after Saint Gaudens began summering in Cornish, NH. I would not want to be in this boat on those seas, but I very much like the colors and composition of this painting. Suffolk County is at the eastern end of Long Island.

- Wyeth, N.C. Winter (1909). Thirty years or so ago, I saw this work on exhibition at the Brandywine Museum in Chadds Ford, PA. Since I didn’t remember the title, it’s taken me that long to find it again. The subject doesn’t particularly grab me, but that composition! Circular but not symmetrical. The way the cloak and the bird complete the light’s circle is so satisfying. I love many of N.C. Wyeth’s works, and was pleased to discover that the Brandywine now has an online catalogue raisonné of them.

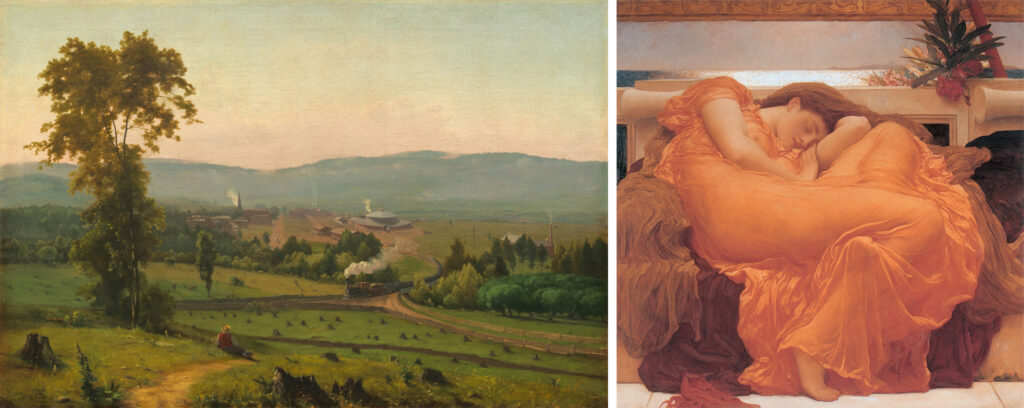

- **Inness, George. Lackawanna Valley (ca. 1856), at the National Gallery, Washington. A scene in Pennsylvania, not far from where I grew up. I still feel a strong pull for low mountains that roll into the distance. Inness (1825-1894) was commissioned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to depict the railroad’s first roundhouse at Scranton, Pennsylvania. As in Thomas Cole’s 1836 The Oxbow (View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm), industrial progress is contrasted with wilderness. I used Inness’s painting in Central Park: The Early Years to illustrate the Hudson River School’s idea that man can look at nature and enjoy it, or he can explore, tame and settle it.

- Leighton, Frederic Lord. Flaming June. The Museo de Ponce (Puerto Rico) was severely damaged in an earthquake in 2020. While repairs are under way, they’ve sent a few of their works out on loan. From October 2022 until February 2024, Flaming June will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. I’m working on a series of posts on Flaming June: can’t promise when they’ll be ready. Check my Instagram feed.

Sculpture

TIED FOR FIRST

- **Frishmuth, Harriet Whitney. The Vine (1923). One of my favorite sculptures – even more so when I look at the abstract works that critics were beginning to acclaim in the decade Frishmuth sculpted this. I did blog posts on The Vine in 2016 (here and here), before I started the Sunday Recommendations.

- **French, Daniel Chester. Spirit of Life (The Trask Memorial) (1915). Spencer Trask (1844-1909) helped Saratoga Springs, NY, regain its reputation as a health resort. The figure French created for his memorial holds a bowl from which water (presumably the famous Saratoga Springs water) falls into a pool. For the lovely model of the head of this figure at Chesterwood, see this post. In the 1910s, Daniel Chester French was America’s most prominent sculptor.

- **[Greek]. Kritios Boy (ca. 480 BC). When watching a video tour of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens (HT Teresa H.), I saw an old (a very old) friend from my first art history course. He’s only three feet ten inches high, but enormously important. Background: around 600 BC, the Greeks began creating life-size sculptures based on Egyptian models. Over the next hundred years, the symmetrical, formal poses of the models were kept, but one sculptor after another taught himself to represent accurately the shapes and details of the human body. By 500 BC, anyone who visited the Acropolis in Athens would have seen a series of kouroi and korai (standing sculptures of men and women) that were lessons in how to represent ears and ankles and knees and other anatomical details. In 490 BC, the Persians invaded the Greek mainland and were repelled. In 480 BC, the Persians attacked again. This time they sacked Athens twice, razing buildings and destroying sculptures. The Greeks regarded their final defeat of the Persians (at sea in 480 BC, on land in 479 BC) not just as a military victory, but as a validation of government by citizens rather than an absolute ruler, and of order over irrationality. (Read Herodotus’s history of the Persian Wars for more, and see my video on Byron’s “The Isles of Greece.”) The Athenians buried the sculptures that had been destroyed on the Acropolis where they fell, and began creating art again. Confident in the superiority of their culture, they carved new sculptures with no trace of the stylized symmetry they had adopted from the Egyptians a century earlier. The new sculptures were all in what is known as the Classical style, in which each figure was shown not as a fascinating assemblage of details, but as an organic whole. We know that style had just begun in 480 BC, because the Kritios Boy, who stands in contrapposto rather than in the Egyptian model of one foot forward, was buried in the rubble left by the Persians – and he’s the only sculpture in this style to be found in the Acropolis excavations. More on the Greek study of anatomy and contrapposto in Innovators in Sculpture.

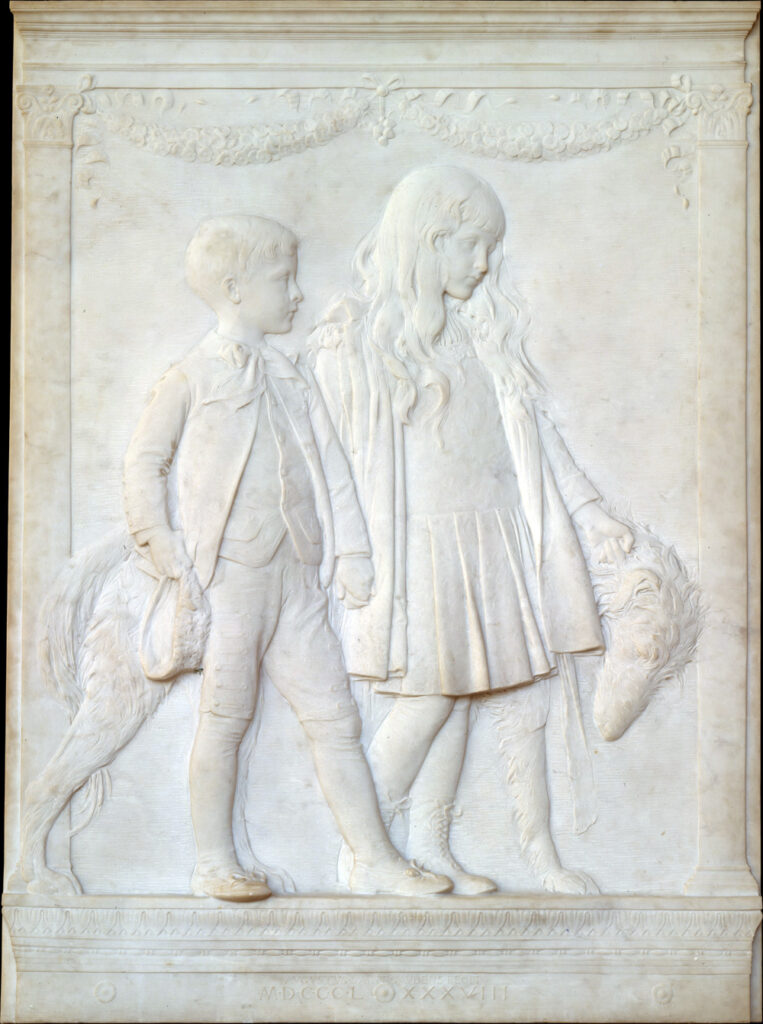

- Saint Gaudens, Augustus. The Schiff Children (1885; this copy 1905). Saint Gaudens, who worked as a maker of cameos in his teens, later used his knowledge to sculpt this beautiful low-relief portrait of two children with a Scottish deerhound. Jacob H. Schiff (1847-1920), an immigrant from Germany, became a prominent banker at Kuhn, Loeb & Co., where he funded the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese War and financed several American railroads. He was a major donor to Jewish charities in the United States and a leader of the Jewish community from 1880 to 1920. Schiff left an estate of about $50 million ($740 million today). He was succeeded at Kuhn, Loeb by his son Mortimer Leo Schiff, who appears as an 8-year-old on this relief. According to a label at the Saint Gaudens National Historical Site, the deerhound belonged to Saint Gaudens, not the Schiffs. In 1905, Jacob Schiff paid for this replica for the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. For more on the career of Saint Gaudens, see Artist-Entrepreneurs.

RUNNERS UP

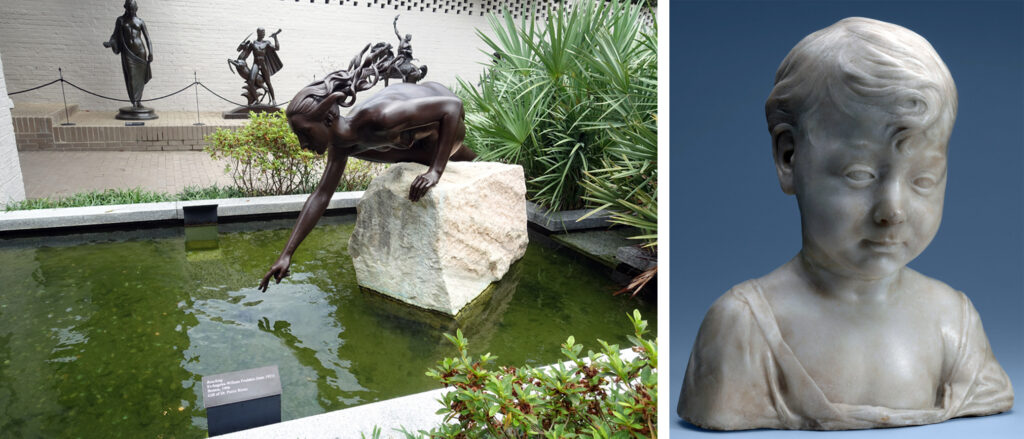

- Frudakis, EvAngelos. Reaching (1996). One of my favorite sculptures at Brookgreen Gardens. Frudakis (one of a family of sculptors) also created The Signer in Philadelphia.

- **Desiderio da Settignano. Young Boy (Christ Child?) (ca. 1460), at the National Gallery in Washington. Look at the the way the marble rises and falls over the cheeks, under the eyes, around the chin. Look at the way the texture of the hair is rendered: you can tell its thickness and the way it curls. Look at the tilt of the head on the neck: it’s just slightly asymmetrical, suggesting movement. Have you ever seen a sculpture that looks so much like a living person? And yet it’s not naturalistic. This isn’t a random boy in a random pose that the sculptor just happened to copy. Desiderio da Settignano (ca. 1428-1464), Bernardo and Antonio Rossellino, and Benedetto da Maiano all worked in Renaissance Florence during the mid-1400s. They produced charming, exquisitely carved works such as this one in a “Sweet Style” inspired by Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna, ca. 1425-1430. (See Innovators in Sculpture, Ch. 8.)

More

- In 2022 I published 3 books: Starry Solitudes: A Collection of Inspiring and Thought-Provoking Poetry (98 poems I’ve recommended over the past five years); Sunny Sundays: Highlights of Five Years of Sunday Recommendations (more here); and Timeline 1900-2021: Events Worldwide, US Politics & Culture, Economics, Science & Technology, Books, Visual Arts, Architecture, Film & TV, Music (more here).

- For more of my writings, see the Books and Essays page. All my books are available in Kindle and/or print format via my Amazon author page. And check out dozens of videos from 2021 on my YouTube channel.

- For favorites from earlier years, see the Favorite Recommendations and Photos link.

- Want wonderful art such as these recommendations delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.