This post, I thought blithely, will be fast and easy. Wouldn’t every gentleman carry a pocket-sized copy of the Code Duello for reference in affairs of honor? I’ll find a printed dueling code and post some screenshots of an edition Alexander Hamilton might have seen, and that’ll be it for “The Ten Duel Commandments.”

This post, I thought blithely, will be fast and easy. Wouldn’t every gentleman carry a pocket-sized copy of the Code Duello for reference in affairs of honor? I’ll find a printed dueling code and post some screenshots of an edition Alexander Hamilton might have seen, and that’ll be it for “The Ten Duel Commandments.”

In my folder of notes for upcoming posts, I found a print-out from a PBS page on the “Code Duello.” It says this code was

drawn up and settled at Clonmel Summer Assizes, 1777, by gentlemen-delegates of Tipperary, Galway, Sligo, Mayo and Roscommon, and prescribed for general adoption throughout Ireland. The Code was generally also followed in England and on the Continent with some slight variations. In America, the principal rules were followed, although occasionally there were some glaring deviations.

Woohoo, 1777! That’s early enough (barely) that it could have been used not only by Burr and Hamilton in 1804, but conceivably by Charles Lee and John Laurens in their 1778 duel.

But I’m a cautious, scholarly type. I prefer to go back to the original printed version to see the context and to make sure nothing has been cut.

The short version of this post and next week’s is: I can’t find any dueling codes printed in the 18th century. The earliest ones date to the 1820s. Furthermore, several of the “Ten Duel Commandments” aren’t in any of the four dueling codes that I have found. Which leads me to the question that’s been obsessing me for two weeks: where did the “Ten Duel Commandments” come from, and what’s their purpose in Hamilton: An American Musical?

Hush, Lin-Manuel, I know you know the answer. And yes, I’ll be mentioning Joanne Freeman’s Affairs of Honor presently.

The rest of you: part of the reason I spend time looking at primary sources is so that I can spend more time thinking about the musical, i.e., about art, which is one of my very favorite things to do. If the dueling codes don’t interest you, skip to the end of the second of these two posts (next week) for thoughts on the role of the commandments in the musical.

The Duel Commandments in the Hamilton Musical

Here are the “Ten Duel Commandments,” paraphrased so I don’t get into trouble for quoting a whole song. The cast recording with lyrics is here.

- Demand satisfaction; if the offender apologizes, the matter ends. Otherwise …

- Find a second to act on your behalf.

- Have the seconds meet to negotiate a peace, or to set a time and place for the duel.

- If the seconds don’t reach an agreement, get a set of dueling pistols and pay a physician to come to the dueling ground. Have him turn around so he can deny seeing anything illegal.

- Duel early in the day, and at a place that’s high and dry.

- Leave a note for your next of kin. Say your prayers.

- Confess your sins and get ready to fight.

- Have your seconds try one last time to negotiate a peace.

- Look your opponent in the eye, take aim, gather your courage.

- Count ten paces, fire!

I’ve found four dueling codes: Royal, Irish, French, American. I’ll give you the context for each, and we’ll see which of the Ten Duel Commandments appear in which codes.

The Royal Code, by Joseph Hamiton

NOTE: Alexander Hamilton’s family was from Scotland. Joseph Hamilton lived at Annadale Cottage, near Dublin. When Joseph Hamilton describes the Hamilton-Burr duel (which he does in several places, in two different works), he mentions no family connection. That strongly suggests there was none.

The Royal Code first appears in Joseph Hamilton’s 1829 work, The Only Approved Guide through All the Stages of a Quarrel: Containing the Royal Code of Honor; Reflections upon Duelling; and the Outline of a Court for the Adjustment of Disputes; With Anecdotes, Documents and Cases, Interesting to Christian Moralists Who Decline the Combat; to Experienced Duellists, and to Benevolent Legislators. The Only Approved Guide is currently available from Dover under the title The Duelling Code.

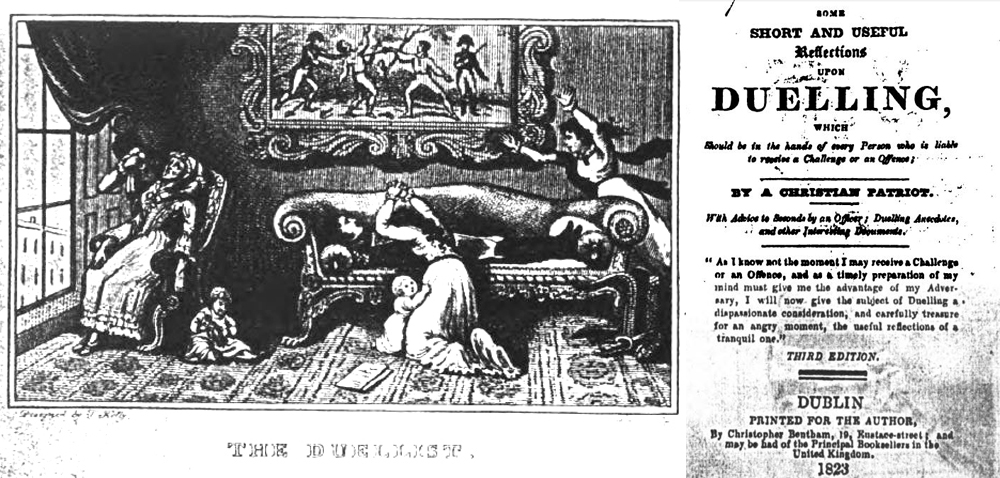

The backstory is crucial for understanding the Royal Code. Joseph (calling him “Hamilton” is just too confusing) was vehemently opposed to dueling. Back in 1823, he published Some Short and Useful Reflections upon Duelling. His attitude is obvious from the frontispiece.

In The Only Approved Guide through All Stages of a Quarrel, published in 1829 – six years after Some Short and Useful Reflections – Joseph also makes his position quite clear:

Before we composed our short reflections upon duelling, with a view to the total abolition of the practice, we carefully perused almost every publication which had appeared upon the subject [i.e., against duelling], and endeavoured to condense into the smallest possible compass, all the arguments which had been urged by the Christian, the moralist, and the man of common sense. We sent copies of that work to several courts in Christendom, and were unsuccessful in our effort to induce a simultaneous movement on the subject. … [Many told him], “It is impossible to eradicate this most pernicious custom.” (p. 16)

What to do when men refuse to give up such a barbarous custom?

Having failed in our endeavours to promote the abolition of the practice, we were next induced to try if we could lessen its attendant evils. We found, in several thousand anecdotes and cases, which we had collected during thirty years, a mass of evidence that the grossest atrocities and errors were committed hourly on the subject. We conceived that such atrocities and errors might possibly in future be prevented, by the extensive circulation of a well-digested code of laws, in which the highest tone of chivalry and honour might be intimately associated with justice, humanity, and common sense; and we were encouraged by several experienced friends, as well as by Plato’s strong assurance, that it is truly honourable to contrive how the worst things can be turned into better.

After carefully perusing our collection of remarkable quarrels … we sketched out a code, consisting of twenty articles, which we submitted to experienced friends in Ireland. We next forwarded manuscript copies to the first political, military, and literary characters of the age, and received the most complimentary assurances of approbation. In May, 1824, we forwarded printed copies for the several courts of Europe and America, as well as to the conductors of the public press, for the purpose of inducing the transmission of such corrections and additions as might, if possible, render it deserving of universal acceptation; and we have now the satisfaction of presenting to the world a collection of highly-applauded rules, for the government of principals and seconds, in our ROYAL CODE OF HONOUR. (pp. 17-18)

I eagerly read the sixty items in Joseph’s Royal Code to see if any of the rules coincided with the Ten Duel Commandments. Hmmm, not so much. Joseph frequently mentions seconds, but no rule explicitly states that you should seek one. In Rule 24, he notes that the duel should be held where there’s easy access to a surgeon, but he doesn’t say that one should be present at the duel (Commandment 4). He states in Rule 32 that a duel shouldn’t be scheduled until each participant has had the chance to “make a proper disposition of his property and trusts, for the advantage of his family, constituents, clients, wards, or creditors.” That’s not the same as “Leave a note for your next of kin” (Commandment 6). (Incidentally, Rule 43 prohibits those who don’t normally wear spectacles from wearing them at a duel.)

So: does the Royal Code have the equivalent of any of the Ten Duel Commandments? Yup. Wanna guess which? Numbers 3 and 8, both of which deal with negotiating peace. For example:

Rule XXIV. When bosom friends, fathers of large, or unprovided families, or very inexperienced youths are about to fight, the Seconds must be doubly justified in their solicitude for reconciliation.

By my count, twenty-four (out of sixty) of Joseph’s rules mention reparation, reconciliation, and/or valid reasons for refusing to duel. Not surprising, given that Joseph was so opposed to dueling.

We can judge the popularity of Joseph Hamilton’s Royal Code by the fact that the 1829 first edition of The Only Approved Guide through All the Stages of a Quarrel remained the sole edition until Dover began publishing reprints in 2007.

The Irish Code

Next up: the 1777 Code Duello on that PBS page that I mentioned at the beginning of this post. PBS cites as its source American Duels and Hostile Encounters, Chilton Books, 1963. Tut, tut, PBS: is that the best you can do for a scholarly citation? Never mind: I can probably track down an early edition just by Googling the opening words or a distinctive phrase.

Hmph, not so easy. The first reference I find is a reprint of the 1777 code in John Lyde Wilson’s The Code of Honor, or, Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling, 1838. Wilson, a Southerner, made up his own set of rules (the “American Code”: see below). He notes at the end of his book, “Since the above Code was in press, a friend has favored me with the Irish Code of Honor, which I had never seen” – so he printed those rules as an appendix to his own. Wilson says he saw the Irish code in the American Quarterly Review, “in a notice about Sir Jonah Barrington’s history of his own times” (p. 35). This turns out to be Barrington’s Personal Sketches of His Own Times, in two volumes, London, 1827.

All right, where did Barrington find the Irish Code?

Sir Jonah Barrington (1756/7-1834) was a member of the Irish bar and the Irish House of Commons. In his 50s, he moved to England and then to France, where he made his living as a writer. According to the authoritative Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, he was known for his panache and humor. Sir J (do you mind if I call you “Sir J”?) devotes a whole chapter, “The Fire-eaters” (pp. 286-318), to describing Irishmen’s love of guns and fighting. Two examples:

One of the most humane men existing, an intimate friend of mine, and at present a prominent public character, but who (as the expression then was) had frequently played both “hilt to hilt,” and “muzzle to muzzle,” [i.e., was a frequent duellist] was heard endeavoring to keep a little son of his quiet, who was crying for something: “Come now, do be a good boy! Come, now,” said my friend, “don’t cry, and I’ll give you a case of nice little pistols to-morrow. Come, now, don’t cry, and we’ll shoot them all in the morning.” – “Yes! yes! we’ll shoot them all in the morning!” responded the child, drying his little eyes, and delighted at the notion.” (p. 289)

And:

He was considered in the main a peacemaker, for he did not like to see anybody fight but himself; and it was universally admitted that he never killed any man who did not well deserve it. (p. 291)

It’s in this chapter on “fire-eaters” that Sir J introduces the rules of dueling. He has just explained that a society called the Knights of Tara, which existed to practice fencing as an art, had faded out of existence:

I can not tell why it broke up: I rather think, however, the original fire-eaters thought it frivolous, or did not like their own ascendency to be rivalled. … Soon after, a comprehensive code of the laws and points of honor was issued by the southern fire-eaters, with directions that it should be strictly observed by gentlemen throughout the kingdom, and kept in their pistol-cases, that ignorance might never be pleaded. This code was not circulated in print, but very numerous written copies were sent to the different county clubs, &c.

My father got one for his sons; and I transcribed most (I believe not all) of it into some blank leaves. These rules brought the whole business of duelling into a focus, and have been much acted upon down to the present day. They called them in Galway “the thirty-six commandments.”

As far as my copy went, they appear to have run as follows: –

The practice of duelling and points of honor settled at Clonmell summer assizes, 1777, by the gentlemen-delegates of Tipperary, Galway, Mayo, Sligo, and Roscommon, and prescribed for general adoption throughout Ireland.

Rule 1. – The first offence requires the first apology … [pp. 293-297, reprinted on the PBS page on the Code Duello]

Immediately after listing these rules, Sir J relates the story of his first duel, which occurred purely by accident: the challenger had sent his second to the wrong man. Citing Rule 7, Sir J’s second insisted that the men were obliged to fight, since they had come to the dueling ground. When, after having duly fired at the challenger, the curious Sir J asked the cause of the quarrel, the challenger replied that according to Rule 8, if an explanation was not requested before a shot was fired, it could not be requested afterward.

Here’s why we’re spending so much time with Sir J: I think the man has his tongue so far in his cheek that it’s a wonder he can pronounce dental consonants. Sir J’s Personal Sketches (including the Irish Code) appeared in 1827. That’s between 1824, when fellow Irishman Joseph Hamilton circulated his draft of the Royal Code, and 1829, when Joseph Hamilton published the sixty-item Royal Code.

I think Sir J read the early draft of the Royal Code and thought, “What namby-pamby stuff! Real Irishmen like to fight too much for all that negotiation. Let me tell you how they actually behave.” Here, for example, is Rule 9:

All imputations of cheating at play, races, &c., to be considered equivalent to a blow; but may be reconciled after one shot, on admitting their falsehood, and begging pardon publicly.

With one exception, in the Irish Code as Sir J prints it, every single rule that talks about shooting requires that at least one shot be fired. None of that sissy reconciliation and reparation business. The exception is Rule 5, which concedes that there is no need for shots if the offender hands a cane to the injured party for use on the offender’s own back.

The bloodthirstiness of the Irish Code was obvious even to American Code author John Lyde Wilson, who noted, “One thing must be apparent to every reader, viz., the marked amelioration of the rules that govern in duelling at the present time.”

Sir J has neatly covered his tracks by saying the rules were passed around only in manuscript copies – so you needn’t bother trying to find a printed edition. And he’s dated the rules fifty years back, long enough to make it difficult for his contemporaries to track down a record and contest Sir J’s account.

In his 1829 The Only Approved Guide through All the Stages of a Quarrel, Joseph Hamilton quotes the whole of Sir J’s rules (which had appeared in print a mere two years earlier) in a section entitled “Obsolete Regulations.” Then he briefly states,

Perhaps we should apologise for copying so many pages from Sir Jonah Barrington, who is generally considered an apocryphal authority (p. 168)

As I said, I think the Irish Code of 1777 is a tongue-in-cheek creation by Sir J in 1827. However, I’ve been known to misinterpret British humor as well as British accents, so I hauled out two substantial fencing and dueling bibliographies. (My day job is with a dealer in old and rare books: this is the kind thing I’m very experienced at.) Thimm’s Complete Bibliography of Fencing & Duelling as Practised by All European Nations from the Middle Ages to the Present Day, 1896, has no entries for the Irish code of dueling – I’ve searched under every title and subject I could think of.

Levi and Gelli’s Bibliografía del Duello, con numerose note sulla questione del Duello, 1903, mentions on pp. xxii-xxiii the recent adoption of a uniform dueling code, which makes a bad practice somewhat better (“a noi sembra evidente come evidente è la convenienza, anzi la necessità, dell’adozione di un unico razionale Codice Cavalleresco [see note 44], il quale, finchè dura il male, valga circonscriverlo …”). Levi & Gelli’s note 44 cites no printed code earlier than the 1820s. They, too, refer to Sir J as the earliest and only source for the Irish code.

I have spent only two weeks seeking evidence of early dueling codes, but Thimm, and Levi & Gelli spent years and years searching out every available work on fencing and dueling. If they didn’t find earlier evidence for the Irish code, then it’s a safe bet there isn’t any.

But for good measure, I logged into OCLC, the best online catalogue of holdings of libraries worldwide. (WorldCat is the layman’s equivalent.) I did various tricky searches for an Irish dueling code printed before Sir J’s time. Again nothing.

For extra good measure – because not all books are in institutions, and because I’m indefatigable when I get the bibliographic bit between my teeth – I searched ViaLibri, my favorite aggregator site for online booksellers. Yet again, nothing.

No matter where I look, the Irish code doesn’t appear until the first volume of Sir J’s Personal Sketches, 1827.

Sir J, you witty liar, I’m done with you.

Oh, wait, I almost forgot the point of this exercise. Only one rule in the Irish Code corresponds to any of the Ten Duel Commandments: that’s number 21. It mentions that seconds are to seek a reconciliation either before the principals meet (Commandment 3) … or (those bloodthirsty Irish!) “after sufficient firing or hits, as specified.”

More

- The credits to the Hamilton soundtrack and the Hamiltome list, as a source for the “Ten Duel Commandments,” Biggie Smalls’ “Ten Crack Commandments” (listen here, read lyrics here). If you still don’t know the difference between rap and Hamilton: An American Musical, here’s your chance to find out.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the twenty-seventh in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack. I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.