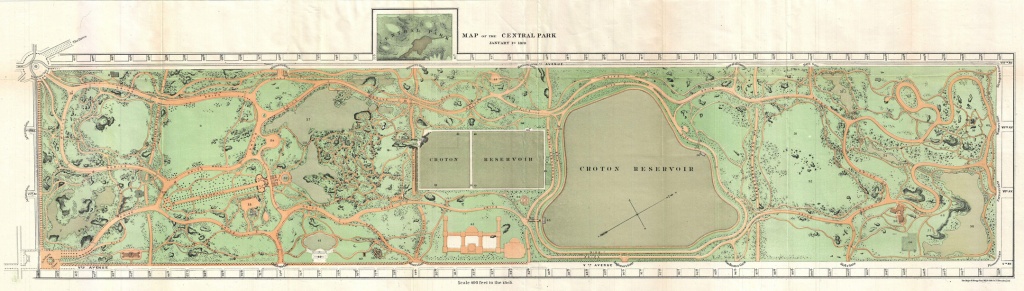

Third in a series of three posts giving the full text of the “Report on Nomenclature of the Gates of the Park,” 1862. The first post in the series includes background information. The second includes gates named for artisans, artists, merchants, scholars, farmers, warriors, hunters, woodmen, mariners, and engineers.

Having thus generalized all the preeminently practical pursuits of life, and acknowledged the obligations that the city is under to those who follow them, it is fitting that a welcome should be extended to the men who devote their energies to making new discoveries that enlarge the field of human action and add to the value of civilized life. The labors of such men as Columbus and Hendrick Hudson can never be forgotten, and their lofty vocation, even if they alone were its representatives, must always be held in grateful estimation by the citizens of New York.

The example set by them has, however, been so diligently followed, that a glance at the numerous expeditions that have been undertaken by Americans within the experience of the present generation, is sufficient to establish the claim of the “Explorer” to a cordial recognition. [NOTE: There is no Explorers’ Gate, but there is a Pioneers’ Gate.]

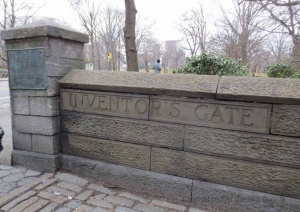

Akin to this idea, and yet widely differing from it, is that of the “Inventor,” whose labors are devoted to the study of natural laws, and to a searching analysis of the various mechanical possibilities that are within the scope of human effort, with a view to combine the results of the knowledge thus obtained in such a way as to confer fresh benefits on the race. To this class of minds we are indebted for the printing-press, the steam-engine, the electric telegraph, and for a thousand other but little less important discoveries.

The various industrial ideas that are constantly working to the advantage of a metropolis, having been thus typified, it seems desirable in a public work like the Central Park, to give attentive consideration to two ideas of a somewhat different character before proceeding to the embodiment of the domestic relations which are of such vital interest to the well-being of every civilized community.

The one is, that the city, although metropolitan by position, is cosmopolitan in its associations and sympathies, and is every ready to extend a courteous welcome to all peaceably disposed “Strangers,” or “Foreigners,” who may be led by inclination or business to pass their time within its boundaries; this welcome being offered, however, not merely as a matter of courtesy, but as a recognition of the fact, that it is highly important, both to the general and the particular interests of the whole nation, that its cities should be visited, and its institutions studied and comprehended by intelligent and industrious travellers from other countries, for by such means only can unworthy prejudices be removed, and incorrect estimates rectified.

The Foreigners’ gate may also, in its sculptural decoration, directly acknowledge the obligation that the owners of the Park are under to liberal and disinterested men of other nations, like Lafayette, for instance, who, in times past, have given active aid, and who, at the present hour, are rendering important service to the best interests of the Republic, of which the city of New York is the commercial centre.

The other idea remaining to be developed is, that, while the success of a metropolis springs, to a considerable extent, from the activity and energetic industry of the individuals who contribute to its material in intellectual advancement, its real prosperity depends, in a far higher degree, on the virtue and integrity of the citizens who live in it, and of the rulers who are intrusted with the control of its affairs; it seems desirable, therefore, to have one gate to the Park, that, under the name of “All Saints,” will respectfully acknowledge the importance of the influence that is exercised, to a greater or less degree, over the whole community by the pure and holy men of all ages, whose beneficent example has helped to raise the standard of public morals, and give elevation to the idea of private character.

Although the Park is intended to afford ample opportunity for personal relaxation and repose to all the hard-working and energetic representatives of manly labor, it has another class of individuals to provide for, whose contributions to the prosperity of the metropolis are no less valuable, and whose claims to a loving welcome are equally deserving of illustration in the nomenclature of the entrance gates.

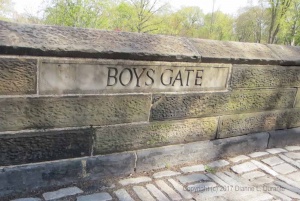

It aims to provide within the city limits an extensive rural play-ground, and a country experience generally, for the whole domestic circle, so that, in future, “The Boys,” “The Girls,” “The Women,” and “The Children” may all have an opportunity to escape, at intervals, from the close confinement of the city streets, and to spend pure and happy hours in direct communication with the beauties of nature.

The Park is already used freely, and enjoyed heartily by troops of young children, and the Children’s gate will help to keep in mind the fact, that, in the course of the next twenty years, the whole army of industrious workers, who are now vigorously laboring for the general welfare, must have received large reinforcements from the band of little ones who are to-day so tender and helpless, or its ranks will already be perceptibly thinned, and its efficiency seriously impaired.

The Boys’ gate and the Girls’ gate will convey the idea that ample opportunity for physical development is considered a necessary part of the free educational system of the city, and will recognize the fact that it is not thought sufficient for the young students of either sex to be liberally provided with schools, school-teachers, and school-books, but that they must also be induced to study freely the works of nature, and be led to an intelligent appreciation of the sermons that are to be found in stones, the books that are printed in the running brooks, and the good that exists in everything that comes from the bountiful hand of the Creator.

There seems, moreover, a particular fitness at the present time in thus publicly recognizing in a pleasure ground like the Central Park, that an importance is felt to attach to the youth of both sexes, not as helpless sons and daughters, dependent on their industrious parents. but individually, as American boys and girls springing directly from God the Father of all, and freely given by the Omnipotent Creator to the whole world; for the sentiment thus conveyed may be looked on as a landmark showing the point to which, in a certain direction, the civilization of the nineteenth century has reached.

The crudest idea of government allows to a single individual despotic power over all his subjects; the feudal system, while limiting the scope, increases the number of the holders of power, and includes the idea of responsibility to some extent, but is still essentially despotic in principle.

The republican system of government, on the other hand, is based clearly on the idea of equal rights, and as civilization advances, this system, under various titles, is practically superseding the others. Feudalism has, however, long retained in “the family” the sway that it has lost in “the state,” and it has been the time-honored custom throughout the world to consider “minors” as the subjects of Divine right of their parents.

The adhesion to the central idea of a republican government has been so thorough and complete in America during the present century, that it has had a gradual influence over this popular habit of contemplating the family relation from a feudal point of view, and as a habit, it may almost be said now to have lapsed into disuse. The change that has taken place, although quite natural, is a result of convictions formed with reference to different objects, and it has not yet attracted attention enough to secure its complete development. It is indeed a common criticism of foreigners on American habits and customs that the younger portion of the community are allowed to occupy a more prominent position than is altogether desirable, and the objection may, perhaps, be permitted to pass without denial, but we cannot fail to perceive that it will, in the future, be far easier to restrain the enlarged idea within proper limits than it was in the past to free it from the selfish popular error with which, for ages, it had been clogged.

If we seek for subjects of illustration suitable for the Boys’ gate, David, with the sling, Casabianca, the young Tell, and other similar examples at once occur to the mind as universally recognized instances of heroism, obedience, and confidence that belong exclusively to the era of boyhood.

For the decoration of the Girls’ gate we have the whole range of the poets, who delight especially in describing this evanescent and suggestive phase of feminine life, and who have given us expressive idealizations of all the more beautiful types of girlish character.

In the Women’s gate, it is not intended to convey the idea that the various industrial pursuits recognized at the other entrances to the Park, are followed by one sex only, for the names of women who have distinguished themselves in the various arts and sciences of life, will readily suggest themselves to the mind of every one, but it is desired to express in an especial manner, a sense of the all-important services that are rendered by women in their domestic capacity alone, and to recognize the fact that as maids, wives, and mothers, they are justly entitled to a hearty recognition as valuable contributors to the happiness and prosperity of the whole community.

A list of twenty names is thus obtained that seems to be somewhat appropriate for the object in view. We have the Artizan, the Artist, the Merchant, the Scholar, the Cultivator, the Warrior, the Mariner, the Engineer, the Hunter, the Fisherman, the Woodman, the Miner, the Explorer, the Inventor, the Foreigner, the Boys, the Girls, the Women, the Children, and All Saints – [sic]

The artistic adaptability of the general system of nomenclature above suggested, has already been proved, and worthy types of the Miner, the Trapper, and the Sailor, are now in existence, that have been conceived by American artists.

At present, it would only be desirable to arrange the gateways with a view to possible elaboration hereafter, for although it can scarcely be considered within the proper scope of the Commissioners to provide out of the Park funds, artistic decoration of a really high character, at all the various entrances, an outlet may readily be left open for future effort in this direction by private subscription, and if such an opportunity is offered in connection with a popular system of nomenclature, it will probably, in course of time, be accepted and improved, for each separate gateway will have a special claim to the affectionate consideration of some particular portion of the community.

In suggesting to the Board a systematic nomenclature that may be representative of the pursuits of the whole people, and of the vocations to which the city especially owes its metropolitan character, the Committee have not been unmindful of the difficulty of giving currency to unfamiliar names.

The Egyptian prison in Centre street, for instance, is called “the Tombs,” by general consent, and unless familiar words and easy names are adopted by the Board, it is possible that the nomenclature of the guide-books may by degrees be superseded by some other which accidental circumstances will provide for ordinary use.

Although a regular system seems to be a desideratum, it is not absolutely necessary, and it is evident that attractive names may be given to the gates without reference to any system, taking one perhaps of a distinguished statesman, another of a patron saint, others again from the constellations, the rivers, mountains, hills, lakes, trees, or flowers, or from the affections or the sentiments, – all would afford a nomenclature, varied, unsystematic, and uncontrolled except by fancy, and from so boundless a field, it would seem easy to draw names sufficient and appropriate; but it has not been found an easy task to select in this way names combining dignity and appropriateness, with that homely quality that will ensure their general acceptance.

While the nomenclature suggested above is the best as a system that has occurred to the Committee, it is quite possible that in individual instances, other names of the same signification may be substituted for those given, though the language has been very thoroughly searched for the words best adapted to express the ideas intended to be conveyed.

Dated New York, April 10th, 1862

H.G. Stebbins, C.H. Russell, And. H. Green, Committee

More

- Andrew Haswell Green was the prime mover of the consolidation of Manhattan and the patchwork of 40-odd cities, towns, and villages surrounding into the City of New York in 1898. He was presented with a gold medal and proclaimed “Father of Greater New York.” A quarter century after his death, he was honored in Central Park with a simple bench backed by five trees symbolizing the five boroughs of New York.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.