This is a rough transcription of a talk given at Hamilton Grange for Fleet Week 2019. I’ll post a link to the video as soon as it’s available. On why the Coast Guard honors Alexander Hamilton, see my post from the dedication of the sculpture in October 2018. All photos are copyright © 2018 Dianne L. Durante unless otherwise noted.

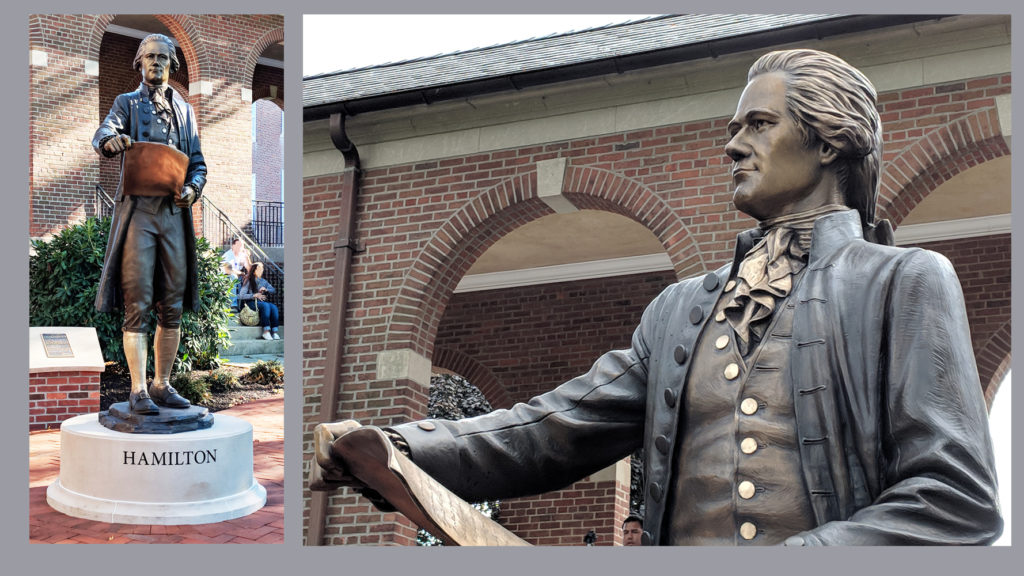

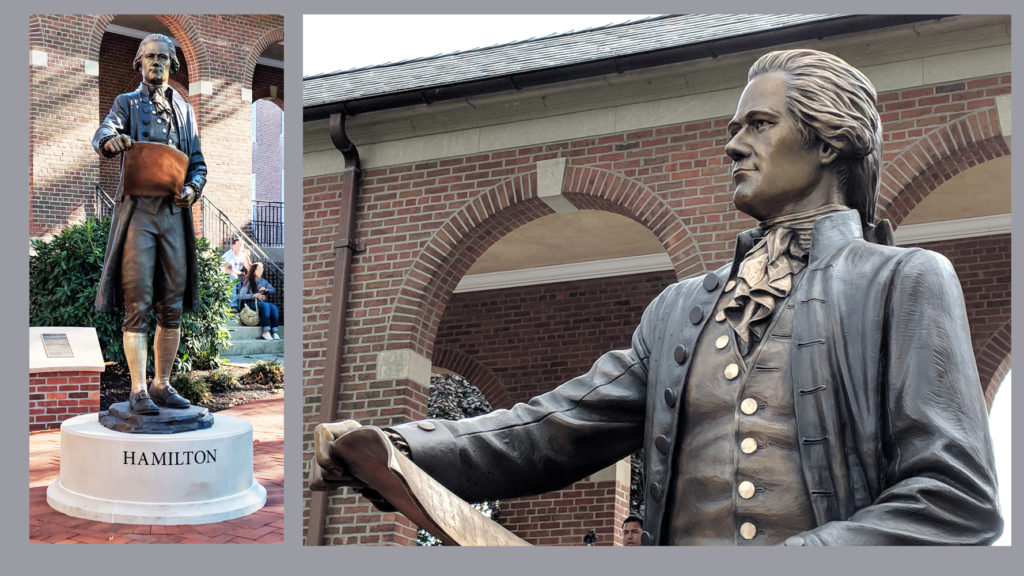

I’m a historian and an art historian, and I love talking about both those topics. But I’m especially happy when I get to talk about history to people interested primarily in art, or about art to people interested primarily in history. Many thanks to the Grange, to the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society, and to the United States Coast Guard Class of 1963 for giving me the chance to talk at historic Hamilton Grange about Benjamin Victor’s sculpture of Hamilton at the Coast Guard Academy.

When the Class of ’63 decided to donate a sculpture of Hamilton to the Academy, many wondered why they’d give a sculpture rather than books, training equipment, computers, and so on. The value of a sculpture has to do with the very basic question of why humans need art. I’m going to circle back to that at the end of the talk, after we look at the details of this sculpture.

I want to start instead with a different question. Why look at the details? After all, we already know what Hamilton looked like.

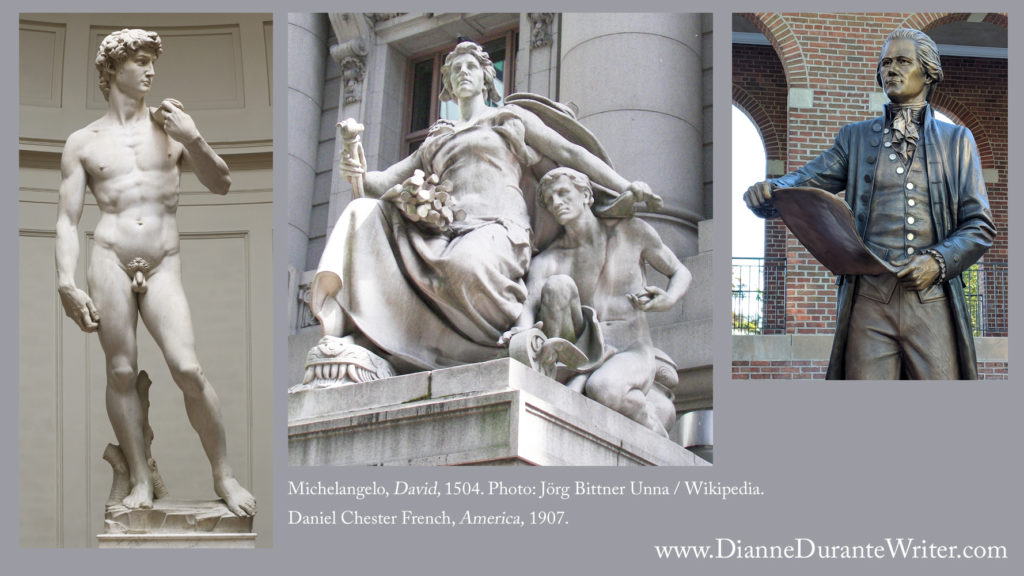

Here’s why: A sculptor starts with a lump of clay or a block of stone. Even if his subject’s face is well known, the artist makes all sorts of choices about how to show him. Will the head be tilted or straight? Will the eyes be looking up, down, or straight ahead? Will the skin be smooth or wrinkled? Will the mouth be frowning, smiling, or neutral? The options go on and on.

Even if the sculptor working on a portrait has been given very specific guidelines, there are still many, many choices to make. The artist must select among them based on which aspects of a person he wants to emphasize. If he does his job well, then when you and I look at the sculpture he created, we notice those details and understand his message about that person.

To highlight the choices Victor made, I’ll compare his sculpture with several others of Hamilton. Because New York City is my bailiwick (or my wheelhouse, if you like), we’ll look at outdoor sculptures of Hamilton in Manhattan. Our aim is to see what Victor conveyed about Hamilton’s character and accomplishments.

Face, Pose & Pedestal: Conrads in Central Park

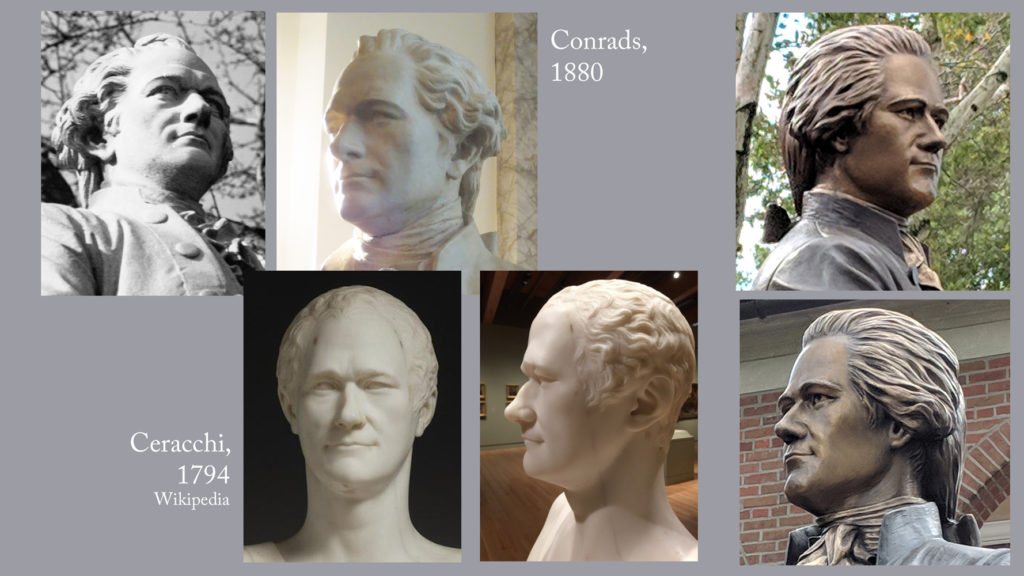

The first sculpture we’ll look at for comparison is by Carl Conrads. It’s the oldest outdoor sculpture of Hamilton in New York City, dedicated in 1880. It stands in Central Park, just west of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The plaster model for it is in the Museum of American Finance in lower Manhattan. (Unfortunately, the MoAF is temporarily closed.)

The sculptures by Conrads and Victor have the same hair style and the same outfit, but there are important differences.

The only sculpture of Hamilton that was carved while he was alive is a bust by Giuseppe Ceracchi, carved in 1794. Since Hamilton purchased a copy, he presumably agreed that it was a good resemblance. Eliza kept a copy of the bust for decades. At the Grange, there’s a version upstairs in the entrance hall.

The Conrads sculpture in Central Park was commissioned by Alexander’s son John. It was based on Ceracchi’s bust, and presumably also agrees with John’s memory of his father.

Let’s compare these the faces of the Conrads and Victor sculptures. Is the man shown by Conrads older or younger than the one shown by Victor? He’s older. There are wrinkles around the eyes and mouth, and the skin is a bit looser as it covers the bones.

Is the Conrads figure more or less relaxed than Victor’s? Less. We can see frown lines on the Conrads figure’s brow. The face of Victor’s sculpture has a smooth brow and a slight smile. He looks younger, more relaxed, very much at ease with what he’s doing.

An important note: I’m not saying one of these faces is better or worse than the other. “Better or worse” is a judgment that depends on the purpose of the sculpture. John Hamilton probably wanted to see his father as he remembered him; and John was only 12 years old when Alexander died in 1804, at age 47. But Hamilton wrote the instructions for the Revenue Marine in 1791, when he was 34, so showing him much younger made sense for Victor.

The Conrads figure stands next to a pillar. His hand rests on it, holding a sheaf of papers. It’s a thick sheaf – perhaps the Federalist Papers, or a report to Congress, or one of his series of polemical essays. The pose is neither pugnacious nor meek. He looks upright and confident, ready to defend verbally whatever the ideas on those page are.

The posture of Victor’s figure is also upright and confident. He’s holding not a roll of papers, but several very large pages, unrolled.

What does the size of those papers tell us? That these are official, important documents. No one would use that size pages for notes for a speech, for example.

Victor’s Hamilton is in the classic pose for reading a decree. How do we know he’s not doing so? Because his mouth is closed.

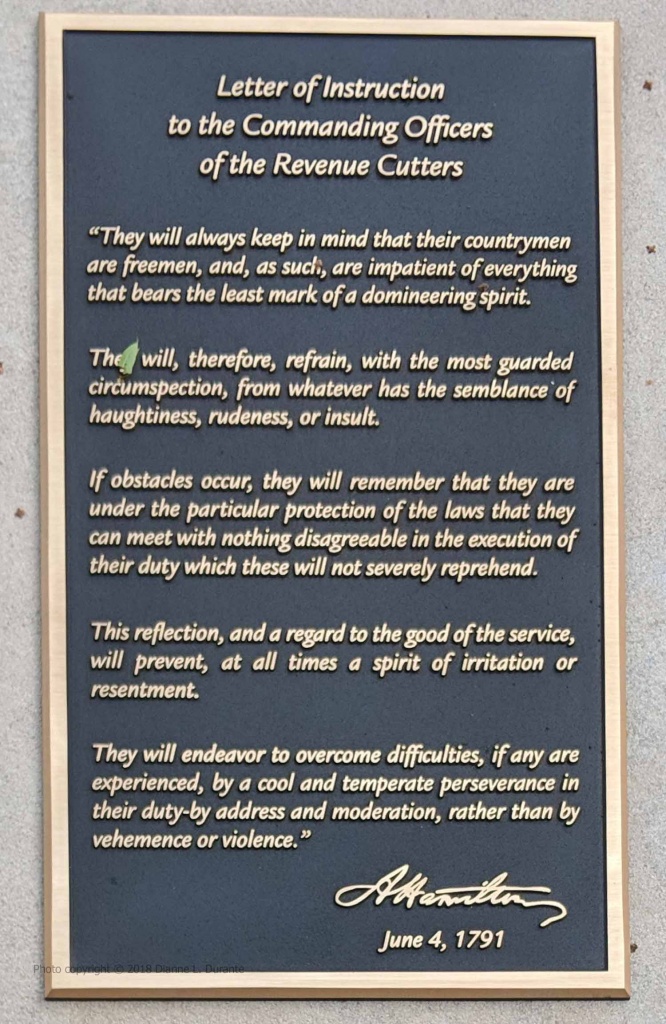

The text on the top sheet of bronze “paper” is the final page of Hamilton’s Letter of Instruction to the Commanding Officers of the Revenue Cutters. The text has been carefully reproduced from the manuscript in Hamilton’s handwriting at the Library of Congress. Victor and his studio assistants laid a full-size photograph of the document on the clay and pricked all the letters so they could create a faithful copy in bronze.

Obviously the Letter is a crucial document for the Coast Guard … but it’s also an example of Hamilton’s careful thought and attention to detail. Americans of 1791 were not accustomed to having a federal government that gave orders and expected to be obeyed. In forming the Revenue Marine, Hamilton was trying to safeguard federal revenue without rousing the hostility of his fellow citizens, especially merchants and seamen. Hence sentences such as, ”They will, therefore, refrain, with the most guarded circumspection, from whatever has the semblance of haughtiness, rudeness, or insult.”

Victor’s Hamilton is definitely not reading this document aloud. Is he even looking at it? No. If he were, his eyelids would be tilted down. Instead of reading it, he seems to be seeing what will result from it. He’s considering its consequences.

That forward-looking orientation is supported by his stance. The Conrads figure is standing still: we can tell because the weight is on the back leg, and the hand is resting on the pillar. In Victor’s figure the weight is on the forward leg and the other heel is about to lift. This figure is about to move, about to take action. He’s still thinking, but he’s not frozen in thought.

The base of Conrads’s sculpture includes a military hat, a sword, and a scabbard. Just below Hamilton‘s feet are thirteen stars, representing the original thirteen states.

On his frock coat is yet another reference to his military service. The medal on his coat is that of the Society of the Cincinnati, a hereditary organization for men who fought in the Revolutionary War. It’s the only ornament this Hamilton wears, which makes it significant. So: although this Hamilton is in civilian clothes, we are being reminded of his military service in the Revolutionary War.

The Conrads figure is seven or eight feet tall. The pedestal is a bit higher than that, and sits atop a hill in Central Park. We have no choice but to look up to this Hamilton.

On the other hand, the pedestal of Victor’s Hamilton is only a foot and a half high. Since the sculpture is over eight feet high, we still look up to him … but he’s much more approachable. You can touch the folds of his frock-coat, if you like. (I do.)

Again: I’m not saying the Conrads or Victor sculpture is better with respect to the pedestal. “Better” depends on the purpose of the sculpture. John Hamilton was constantly struggling to have his father’s contributions recognized: the sculpture he commissioned insists that Hamilton be looked up to. Victor’s Hamilton is meant to inspire Coast Guard cadets and staff. The immediacy of having him within reach helps achieve that.

Let’s more briefly compare Victor’s sculpture with a few other sculptures of Hamilton.

Patina: Partridge at Columbia

Manhattan has two sculptures of Hamilton by William Ordway Partridge, one at Columbia (dedicated 1908) and one near Hamilton Grange (dedicated in 1893 at the Hamilton Club of Brooklyn; donated to the Grange in 1936). Both of Partridge’s figures wear frock coats, so we’re again seeing Hamilton as a civilian. In both, the figure has his chin up and is gazing forward.

The poses in the Partridge sculptures are more dynamic than that of Conrads’s figure. In the one at Columbia, Hamilton’s proper left arm is twisted back as he steps forward. It’s not a pose one would hold for long: he seems to be in mid-motion, mid-gesture. A small role of papers in this figure’s hand suggests notes for a talk. Hamilton seems ready to persuade people to go along with his plans and his point of view.

You’ve probably noticed by now that Victor’s sculpture has several different patinas – it’s not all the same tone, as Partridge’s two bronze sculptures are. Adding variations in color to a sculpture is unusual enough to attract attention. If the colors have no purpose other than novelty, however, then they’re just distracting. So what do these variations achieve?

In the photo at the far right, I’ve darkened the parts with a lighter patina (the calves, vest, buttons, and cravat) and made the eyes and face brighter. Having those three bright spots makes our eyes jump about. It’s difficult to settle on one part of the sculpture, which means it’s difficult to decide what’s the most important feature.

In the sculpture as it is, the lighter parts lead our eyes upward: calves to buttons to cravat to face. A figure can express a great deal with posture and gesture, but in a portrait sculpture, the emphasis ought to be on the face. The use of a different-color patina helps make that happen here.

Inscriptions: Partridge at the Grange

We saw with the Conrads sculpture in Central Park that the pedestal can help convey a message about the figure it supports. Partridge’s sculpture at the Grange has a simple inscription on the front of the pedestal: “Hamilton 1757-1804”. On the left and right sides of the pedestal are four quotes that describe Hamilton as a man who helped implement the Constitution, as an orator, as an intellectual, and as a military hero.

- From Guizot: “There is not in the Constitution of the United States an element of order, of force or of duration which he has not powerfully contributed to introduce or caused to predominate.”

- From Story: “The model of eloquence and the most fascinating of orators.”

- From Stevens: “His rare powers entitle him to the fame of being the first intellectual product of America.”

- From Ames: “The name of Hamilton would have honored Greece in the days of Aristides.” [Aristeides the Just was an Athenian general during the Persian Wars. Herodotus called him “the best and most honourable man in Athens.”]

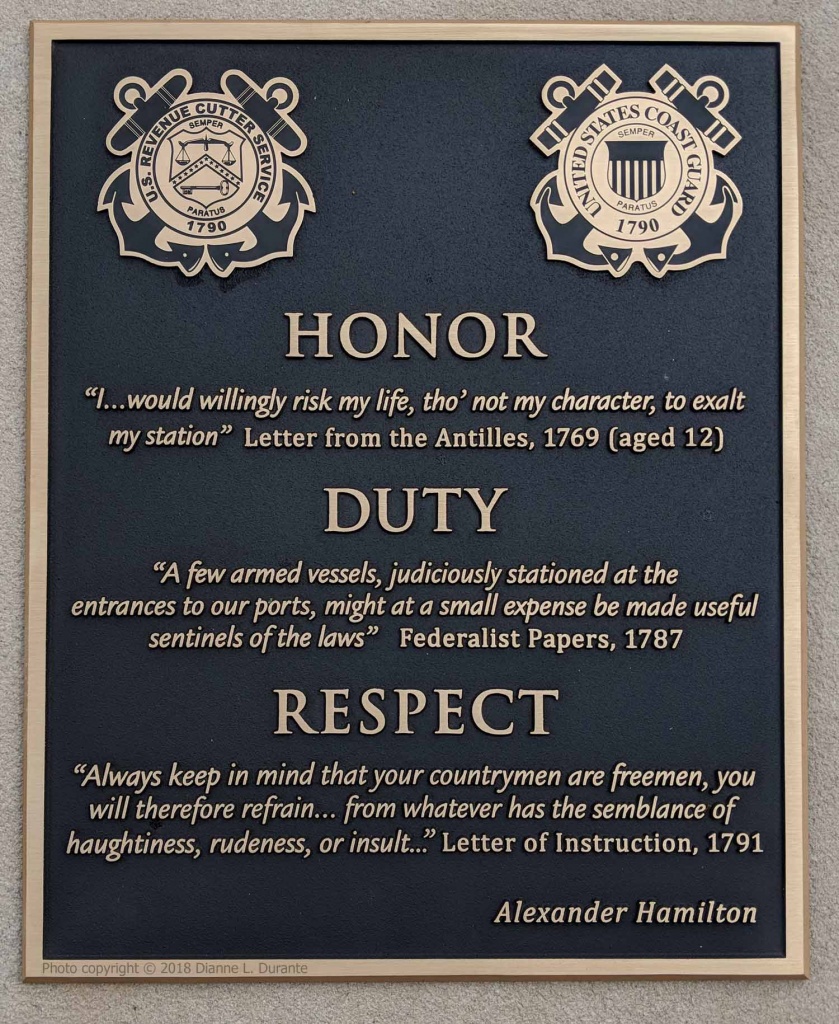

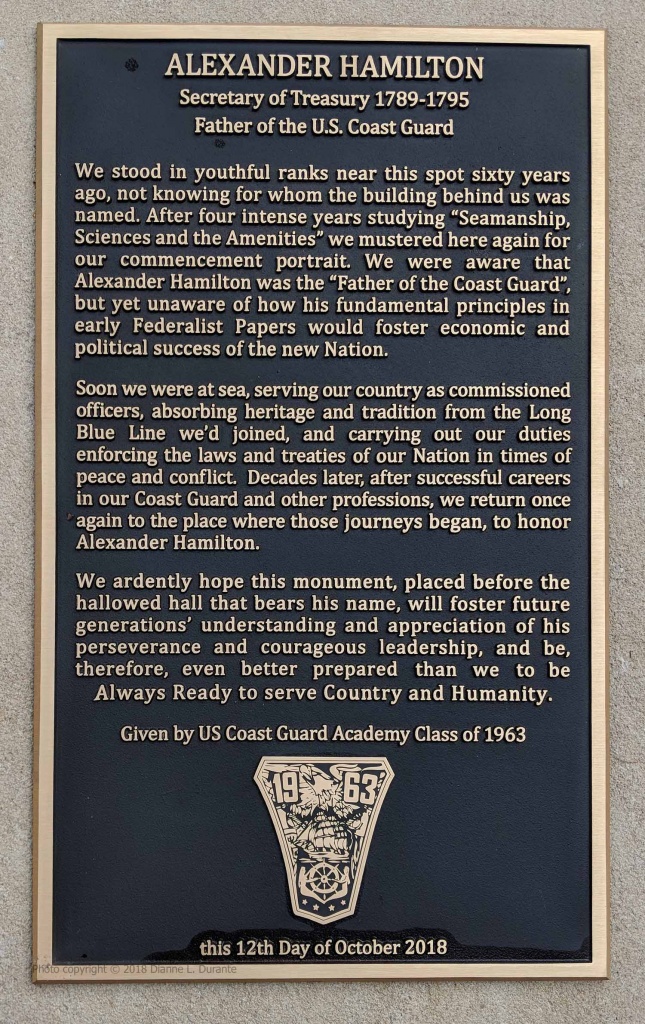

At the Academy, Victor’s sculpture has a setting designed by landscape architect Brian Kent. Behind the figure are five plaques set in an arc.

- The first plaque, at the far left, includes part of Hamilton’s 1791 instructions to the Revenue Marine: the same text as the document Hamilton holds.

- The second plaque includes quotes of Hamilton regarding honor, duty, and respect. This highlights Hamilton as a role model for virtuous behavior.

- The third plaque is the dedication and tribute from the Class of ’63, honoring Hamilton for his courage and perseverance. Again, Hamilton is presented as a role model.

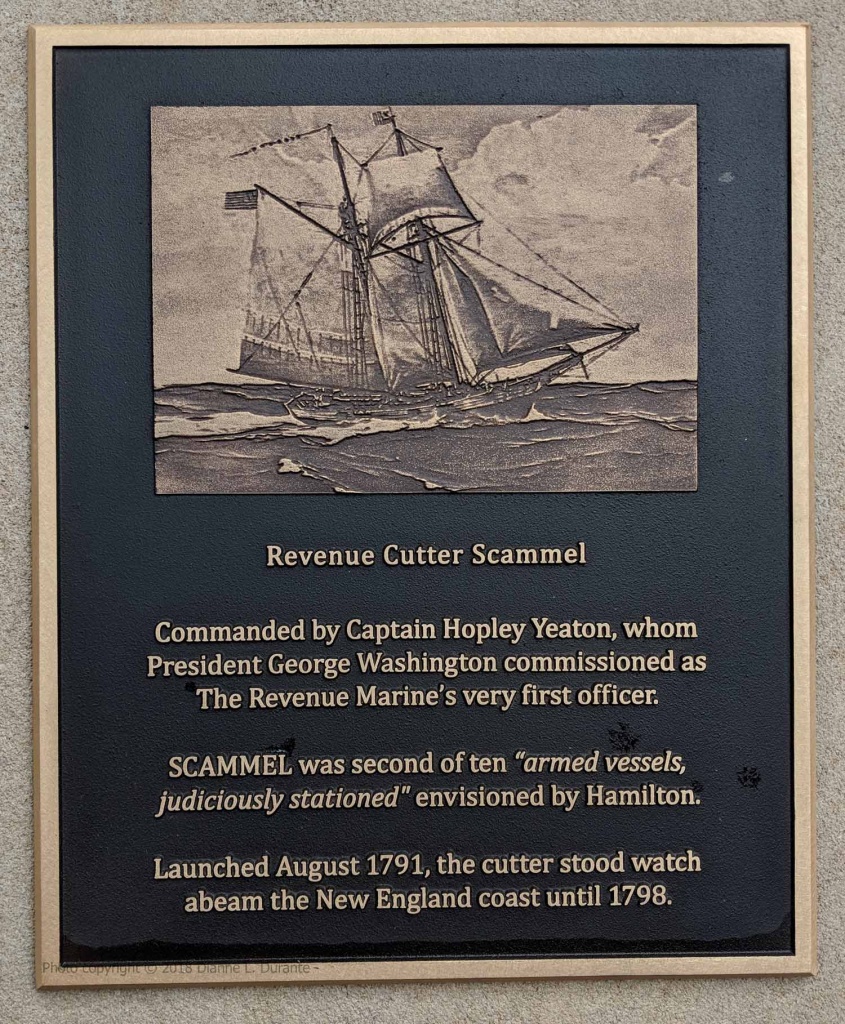

- The fourth plaque shows one of the early revenue cutters, so it’s related to the Coast Guard.

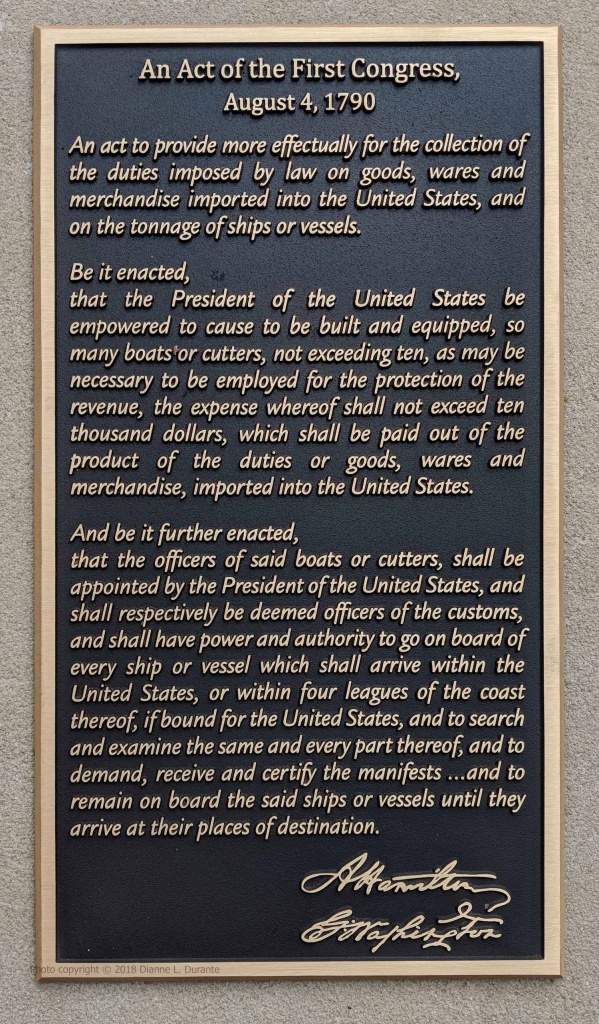

- The fifth plaque reproduces the text of the 1790 Act of Congress creating the Revenue Marine, with the signatures of George Washington and Hamilton.

Taken together, these five plaques highlight Hamilton as the Father of the Coast Guard and as a role model.

Setting: Weinman at the Museum of the City of New York

We’ll look at one more sculpture of Hamilton, dedicated at the Museum of the City of New York in 1941. Its face is similar to the face of Conrads’s figure, but the frown appears to be even deeper. The pose is similar to the Conrads and Partridge sculptures: Hamilton is standing beside a pillar, holding a roll of papers, twisting slightly to one side. The sculpture is in a lovely marble niche topped by an American eagle.

The setting of the Hamilton at the Museum includes the block-long facade of the Museum, which contains a second niche holding another sculpture. Even though the figures are at opposite ends of the building, in combination they convey a message that Hamilton alone would not.

If the sculpture at the other end were Aaron Burr, it would remind us of the very different characters, goals, and methods of those two men, and of Hamilton’s death at Burr’s hands. But the sculpture is not Burr.

If the sculpture at the other end were Thomas Jefferson, it would remind us of his healthy exchange of ideas with Hamilton regarding the nature of the United States government … or their “battle for our nation’s very soul,” if you like. But the sculpture at the opposite end is not Jefferson.

If the sculpture at the other end were George Washington, it would remind us of Hamilton’s military career and of his service as secretary of the Treasury during Washington’s presidency. But the sculpture at the opposite end is not Washington.

The figure at the opposite end of the Museum’s façade is De Witt Clinton, who served for almost two decades as either mayor of New York City or governor of New York State. Clinton is famous for promoting the Erie Canal, which made New York City the transportation hub for the Midwest and the East Coast. That led to New York becoming America’s business center. Putting Hamilton in combination with Clinton reminds us that Hamilton fostered business and the growth of New York City: highly appropriate for the facade of the Museum of the City of New York.

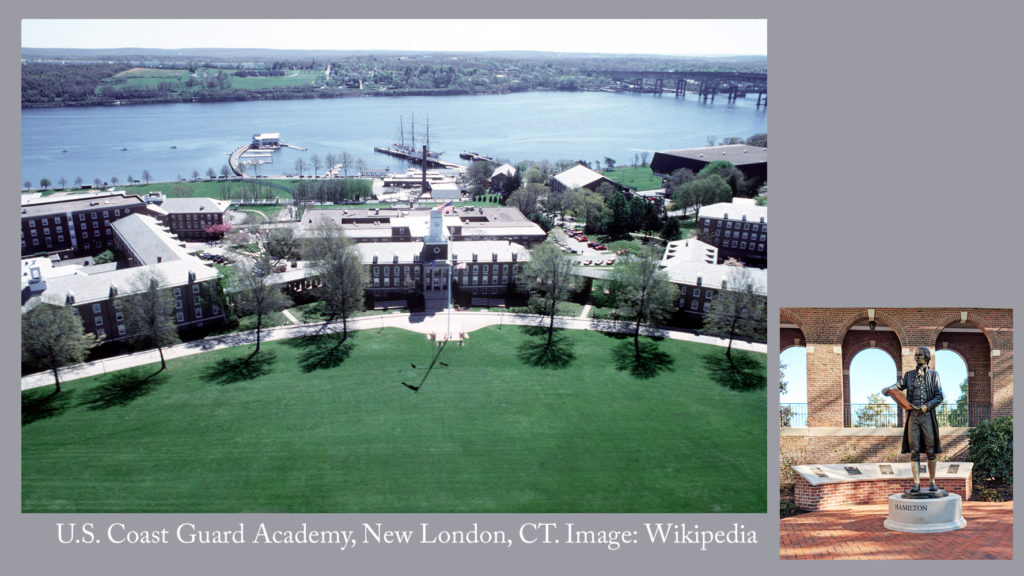

Clearly the broadest setting of a sculpture can affect how it’s interpreted. What’s the setting of Hamilton at the Academy?

The Coast Guard Academy has many memorials on shaded walks in secluded areas. Their settings invite us to stop and contemplate what they commemorate. But Hamilton is set against the arches next to Hamilton Hall. Hamilton Hall and the parade ground it faces are the heart of the Academy campus. Cadets, staff, and visitors cannot miss Hamilton.

Hamilton has been positioned so that his gaze is fixed on the flagpole at the front and center of the parade ground. What’s the message? He’s not a visionary gazing at a pie-in-the-sky future. His focus on the flag suggests that he’s considering the long-term good of his country.

The position of Hamilton on the Academy’s campus says that Hamilton is extremely important for the United States Coast Guard Academy, and the details tell us why that is so.

The message of Victor’s Hamilton

The papers in Hamilton’s hand show that he’s working on a specific, practical goal: the creation of the Revenue Marine. He’s not merely a dreamer: he’s about to step forward, into action, and he’s fixing his gaze on the symbol of the United States. His youthful face and slight smile tell us he’s calm and at ease, facing a problem but confident that he can solve it. The posture and expression suggest a style of thought: confident, detail-oriented, but long-sighted as well.

This is what Victor conveyed by choosing these particular details of expression and pose, and what Brian Kent conveyed by designing this particular setting. These details were not inevitable or obvious. Kudos to Ben Victor, Briant Kent, and the Class of ’63, and all those involved for creating such a work when facing a very tight deadline.

What’s the use of a portrait sculpture?

Returning to our original question: what’s the good of a portrait sculpture? After all, real people have flaws that we don’t want to emulate.

Washington led his country in war and in peace as no one else could have … but he owned slaves.

Dr. J. Marion Sims did research that saved thousands of women from horrible deaths due to mysterious “female complaints” … but his first patients were slaves, and he could not prove he had their consent.

Jose Marti roused Cubans to fight for independence from Spain … but he ran into battle against the orders of his military commanders and was shot dead.

Alexander Hamilton fought bravely in the Revolutionary War. He wrote many of the Federalist Papers. He helped implement the Constitution and get the new United States government on its feet. He had a grasp of business and finance unmatched in his generation. … but he had that notorious affair with Maria Reynolds. In fact, he met her around June 1791, the time when he was writing the Instructions for the Revenue Marine.

Why do we need images of such flawed people?

Well, here’s the thing. Unlike a photo or a video, a sculpture is selective. It can emphasize a person’s particular, specific traits or accomplishments, as we’ve seen in the sculpture of Hamilton at the Academy. It can remind us of what’s admirable about someone, and thereby remind us of values we share with that person and want to hold on to.

For the cadets and staff at the Academy, for its graduates and for its visitors, the sculpture of Hamilton does’t replace the manuals, mottos, physical exercise, or days at sea. But it is a quick visual reminder of Hamilton’s achievements and his style of thought. To give direction to their daily tasks and their future plans, that’s very valuable.

Alexander Hamilton’s achievements and style of thinking aren’t what every single person needs as inspiration. The art that’s right for each one of us depends on what each of us as an individual thinks is important. But whatever those values are, the right work of art can condense them into a visual package we can call to mind in a split second.

In a world that includes Twitter and Snapchat and 732,000 Netflix series, a work of art can remind us how the world – and the people in it – can and ought to be. Art – sculpture, painting, music, movies – is not a frill. It’s essential.

More

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my Sunday Recommendations list: details here. Want to say, “Well done, Dianne”? See the link on the right, just below the list of recent blog posts.