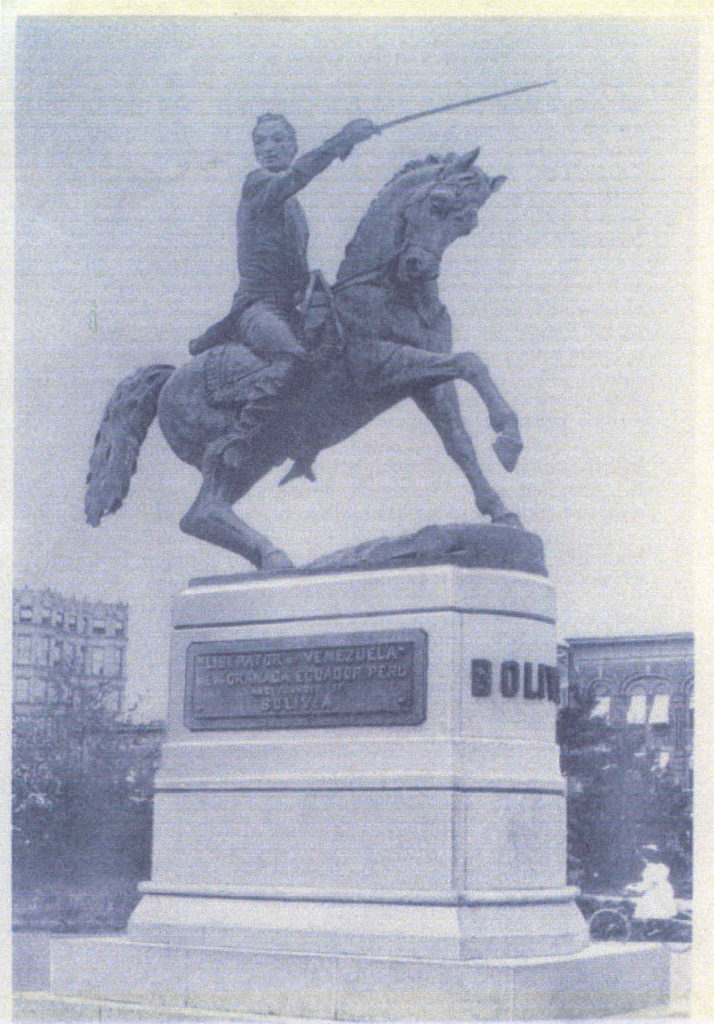

- Sculptor: Sally James Farnham

- Pedestal: Clarke and Rapuano

- Dedicated: 1921; relocated and rededicated 1951

- Medium and size: Bronze (13.5 feet), granite pedestal (20.3 feet)

- Location: Central Park South at Avenue of the Americas

June 24, 1821: Bolivar Wins the Battle of Carabobo

The victory of Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) over Spanish royalists at the Battle of Carabobo sealed the independence of Venezuela – after two failed attempts and ten years of war, during which between 80,000 and 100,000 Venezuelans either died or emigrated.

Bolivar’s View on the Struggle for Latin American Independence

In the midst of the battle for independence from Spain, Bolivar wrote to a friend:

The abuses, neglects, lack of organicity, are the result of causes it has not been in my power to correct, for many reasons: first, because a man in brief time and with scant general knowledge cannot do everything: not well, not even badly; second, because I have had to devote myself to expelling the enemy; third, because in our frightening chaos of patriots, traitors, egoists, white, colored, Venezuelans,Granadans, federalists, centralists, republicans, artistocrats, good and bad, and the whole caboodle of hierarchies in which every band is split, there are so many conditions to be observed that, dear friend, I have been forced many a time to be unjust in order to be politic – and when I’ve been just I’ve paid for it! — Simon Bolivar, Letter to Antonio Narino, April 1821

In a letter to Bolivar, Daniel Webster (whose statue stands on the 72nd St. traverse in Central Park) hailed him as “the image of our venerated Washington.” What intrigues me is how unlike Washington Bolivar was. He professed to admire the American constitution, but served in several of the countries he liberated as absolute ruler; and he died at age 47, in exile, with barely the shirt on his back. A month before he died he wrote bitterly to a friend, “America is ungovernable. Those who serve the revolution plough the sea. The only thing to do in America is to emigrate.”

The City Beautiful Movement (part 3): Manhattan’s First Bolivar

See also Part 1 (Pulitzer Fountain) and Part 2 (Surrogate’s Court).

Farnham’s statue of Bolivar at the north end of Avenue of the Americas is the third sculpture of the Liberator designed for New York. The first, by R. de la Cora (or Cuva?), was given to the city by the government of Venezuela in 1884. It was condemned as a “monsterpiece,” and indeed it was an unattractive work, with the horse disproportionately small, strangely muscled, and rearing awkwardly.

The city put the first Bolivar at an out-of-the-way site near Central Park West and 82nd St. Even there, it was ridiculed so often that the government of Venezuela offered to pay for a new statue. The de la Cora Bolivar was removed from its pedestal in the late 1880s or 1890s.

(Special thanks to George Haskins, who provided the photo of the first Bolivar from Saltus and Tisne, Statues of New York, 1923.)

Venezuela then found that it could not simply present a different sculpture. Members of the National Sculpture Society, founded in 1893 to promote excellence in sculpture (early members included Daniel Chester French and Augustus Saint Gaudens), examined a clay model in 1897 and politely opined that it “failed to suit the artistic taste of New York.”

In the 1890s New York City’s government decided it was time to start controlling what sculptures were erected on City property: see the essays on the City Beautiful movement, part 1 (on the Pulitzer Fountain) and part 2 (on Surrogates’ Court). From 1898 on, potential donors had to get the approval of the Art Commission for permanent installation on city property of any work of art. Today, the Art Commission still oversees the placement of sculpture on city property; see Encyclopedia of New York City pp. 16-17 for more details.

Diedrich’s Greyhounds

After Venezuela’s second offeringwas rejected, the Bolivar pedestal remained empty until Farnham’s statue was dedicated in 1921. … Except for one April night in 1916, when a boisterous group of artists and friends helped Hunt Diederich (Wilhelm or William Hunt Diederich, 1884-1953) hoist his pair of bronze greyhounds onto the pedestal. The dogs had been recently displayed at a Paris salon, but had been rejected by a jury at the National Academy of Design. See a sample of Diederich’s work here.

The New York Times account of this romp in the Park is so vivid that its reporter must have been on the scene. The comments of the conspirators provide an glimpse into what was considered avant-garde art among the Bohemian set in 1910s in New York. (Less than a year later, Marcel Duchamp and several friends climbed to the top of the Washington Arch and declared the independence of Greenwich Village. Their Declaration consisted of the word “whereas,” repeated over and over.)

The New York Times’ account is well told, and I haven’t seen it reprinted, so herewith, some extensive excerpts (4/5/1916):

The leading machine was a taxicab. On the front seat with the chauffeur was an enormous bronze of two hounds playing. It was about seven feet long and three wide. A tall man with a small blonde mustache shouted directions in an accent slightly German to the chauffeur and to five or six occupants of the car. On the top was a ladder, and through the window of the cab projected a long bar and several planks.

This car was followed closely by a low gray limousine with six other occupants, who were talking and laughing loudly, and wondering in loud tones “if the police will catch us.” …

A ladder and two planks were swung to the top of the ten-foot pedestal, ropes were put around the bronze group, and, on the orders of the blonde man, given in a suppressed whisper, three men on the top of the pedestal and seven others below heaved and tugged.

“More men on top! More men on top!” shouted the blonde man, and in a moment two others were up. “Now heave!” came the command, and the scraping of the metal base on the stone whined in the night.

The woman with the party clapped her hands and jumped up and down. “Oh, the hounds are up! And the cops didn’t catch us, and no matter what the critics say, the dogs of Paris will bark in the park.”

The man whom the others called Nicholas and the poet swept his hat from his head with his hand, clasped his hand to his breast, and cried: “Ah, Hunt, it is up. It is up. The hounds. The hounds. What do we care for the critics or the academicians or the Art Commission or the cops now? The dogs are up. Let them take them down if they can, if they will. But they will not when the riders see the beautiful dogs playing.” …

[Louis W. Fehr, Secretary of the Park Board] said that all statues or ornaments in public parks must be approved by the Landscape Architect and the Municipal Art Commission before they were put up. …

The police did not discover the statue till long after the beautifiers of the landscape had gone away. And when they had found it they said, It was not up to them to do anything, so the pedestal was still occupied by the greyhounds up to 4 o’clock this morning.

From the Times on the following day, 4/6/1916:

General Simon Bolivar of Venezuela held title to his unoccupied pedestal in Central Park yesterday against the attack of Modern or Impressionist Art, represented by William Hunt Diederich’s “Levriers,” or “Greyhounds,” only with the timely aid of park police reinforcements. Three hours after they had been placed on the equestrian statue base by friends of the artist the playing dogs of Paris were thrown ten feet to the ground and “damaged almost beyond repair.” …

Although the affair did at first smack of a Bohemian prank, the artists who put up the canine effigy say they did have a serious desire to give it to the city, and that since General Bolivar deserted his post more than fifteen years ago the blank pedestal on the eminence had no artistic value whatever. As Diederich told Paul Manship, the artist, who thought it would be in keeping with the spirit of modern art and impressionism to invade Central Park with a gift, and not with the usual spirit of thievery, “there is that pedestal screaming for a bronze, and there are my hounds whining for a pedestal.” …

The Parks Department was in a quandary, too. Many have stolen from the parks, but few have given. It was so unusual that it was startling.

Then they ran across the section of the ordinances reading:

“No horse or other animal shall be allowed to go at large in any park or in any park street, except dogs that are restrained by a chain or leash not exceeding six feet in length.”

“Are they leashed and muzzled?” asked the [New York Police Department] Lieutenant. “If they’re not, catch them and bring them in.”

That marked the downfall of the dogs of Paris.

Changing Taste in Art

In 1899 Layton Crippen, art critic of the New York Times, wrote:

Let a tract of land be selected in some secluded country vale far from the city’s bustle (as far away as possible) and there let the marble and bronze figures of the departed be removed. In a few years – who knows – the equestrian statue of Gen. Bolivar might become almost beautiful with Virginia creeper, and even the Worth Monument [Fifth Avenue at 25th St.] be picturesque, with clinging ivy. Thither might be taken the seated figure of William H. Seward which now occupies valuable room in [the southwest corner of] Madison Square, together with the equestrian Washington, with the abnormal tail to the horse, from Union Square. Like the people in the Mikado’s song, neither Horace Greeley nor William E. Dodge would be missed from the neighborhood of Broadway and Thirty-third Street, nor would the loss of the figure of Dr. Sims, with the combination toga-overcoat, be deeply felt by the frequenters of Bryant Park. — Layton Crippen, “Unsightly New York Statues,” New York Times 5/7/1899

Bolivar and the Avenue of the Americas

By 1949, Sixth Avenue had been renamed “Avenue of the Americas,” and the City was collecting statues of South American heroes to adorn it. The Parks Department wanted to move Bolivar from West 82nd St. down to Central Park South. City elections that year brought a vituperative exchange over funding for a new Bolivar site and pedestal between a candidate for Manhattan borough president and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses (“Ignorance could rise to no dizzier heights … There isn’t one iota of accuracy or decency in your comments”). In the end, the government of Venezuela stepped in with funds to have the piece moved to its present location, where it faces San Martin and Jose Marti.

More

- For more on this sculpture, see Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan.

- For more on the South American independence movements, I do not recommend John Lynch’s The Spanish American Revolutions 1808-1826. It’s the worst type of modern historiography: wallowing in concretes, deliberately avoiding value judgments. Reading Lynch, you could discover the percentage of the Peruvian mestizo population engaged in agriculture in 1824, but not the three most important figures in the South American independence movements.

- Much better is van Loon’s 1943 Life and Times of Simon Bolivar. Some of van Loon’s assumptions and principles are moot, but he gives a broad view of South America during the colonial period that’s invaluable if you’re just beginning to learn about the period.

- Incidentally, van Loon’s 1921 Story of Mankind is a well written and entertaining world history. Originally directed at young people, it’s also suitable for adults filling in gaps in their knowledge. The Story of Mankind is in the public domain, and can be downloaded free on the Net; it’s also still in print, and availabe as an ebook.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.