- Sculptor: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

- Date: 1936

- Location: Stuyvesant Square, between 16th and 17th Sts., west of Second Ave.

Whitney, Peter Stuyvesant, 1936. Stuyvesant Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Whitney, Peter Stuyvesant, 1936. Stuyvesant Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

Whitney, Peter Stuyvesant, 1936. Stuyvesant Square, New York. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

August 1664: Peter Stuyvesant surrenders New Amsterdam to the British

Late in August 1664 four British frigates sailed through the Narrows and trained their guns on Fort Amsterdam, the run-down defense of a thriving Dutch commercial town. In the name of the Duke of York, brother King Charles II, Colonel Nicolls offered every man his “Estate, life, and liberty” if the town capitulated peacefully. Director-General Peter Stuyvesant at first flatly refused to surrender, but under pressure from the residents, finally signed the Articles of Capitulation. In September, New Amsterdam and New Netherland officially became New York.

For a serious, scholarly account of Stuyvesant’s tenure as director general and the surrender of New Amsterdam, read Burrows & Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York pp. 41-73. The descriptions below – much more amusing, but much less accurate – are from Knickerbocker’s History of New York, 1809. Purporting to be written by a cantankerous elderly gentleman named Diedrich Knickerbocker, the History was in fact the work of rising literary star Washington Irving. Later editions warned that it was a “whimsical and satirical work, in which the peculiarities and follies of the present day are humorously depicted in the persons, and arrayed … in the grotesque costume of the ancient Dutch colonist.”

This statue of Stuyvesant stands on land that was once part of his farm.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

The sculptor, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1941), also produced the Inwood (Washington Heights) War Memorial at Broadway and 168th St. In 1930 she founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, devoted solely to twentieth-century American art, with a core collection of 500 pieces that the Metropolitan Museum had refused to accept as a gift. The Whitney Biennial, held in even-numbered years, is one of the most prestigious contemporary art exhibitions in the country. If you want to see the sort of art that’s currently critically acclaimed, it’s the place to go. Two glasses of wine on an empty stomach will put you in the right state of mind.

Excerpts from Washington Irving, Knickerbocker’s History of New York, 1809

Click here for the full Gutenberg text.

To say merely that he was a hero would be doing him great injustice; he was, in truth, a combination of heroes; for he was of a sturdy, raw-boned make, like Ajax Telamon, with a pair of round shoulders that Hercules would have given his hide for (meaning his lion’s hide) when he undertook to ease old Atlas of his load. He was, moreover, as Plutarch describes Coriolanus, not only terrible for the force of his arm, but likewise for his voice, which sounded as though it came out of a barrel; and, like the self-same warrior, he possessed a sovereign contempt for the sovereign people, and an iron aspect, which was enough of itself to make the very bowels of his adversaries quake with terror and dismay. All this martial excellency of appearance was inexpressibly heightened by an accidental advantage, with which I am surprised that neither Homer nor Virgil have graced any of their heroes.

This was nothing less than a wooden leg, which was the only prize he had gained in bravely fighting the battles of his country, but of which he was so proud, that he was often heard to declare he valued it more than all his other limbs put together; indeed, so highly did he esteem it, that he had it gallantly enchased and relieved with silver devices, which caused it to be related in divers histories and legends that he wore a silver leg. …

Irving, Knickerbocker’s, book 5

There is something exceedingly sublime and melancholy in the spectacle which the present crisis of our history presents. An illustrious and venerable little city–the metropolis of a vast extent of uninhabited country–garrisoned by a doughty host of orators, chairmen, committee-men, burgomasters, schepens, and old women–governed by a determined and strong-headed warrior, and fortified by mud batteries, palisadoes, and resolutions–blockaded by sea, beleaguered by land, and threatened with direful desolation from without; while its very vitals are torn with internal faction and commotion! Never did historic pen record a page of more complicated distress, unless it be the strife that distracted the Israelites during the siege of Jerusalem, where discordant parties were cutting each other’s throats at the moment when the victorious legions of Titus had toppled down their bulwarks, and were carrying fire and sword into the very sanctum sanctorum of the temple!

Governor Stuyvesant having triumphantly put his grand council to the rout, and delivered himself from a multitude of impertinent advisers, despatched a categorical reply to the commanders of the invading squadron, wherein he asserted the right and title of their High Mightinesses the Lords States General to the province of New Netherlands, and trusting in the righteousness of his cause, set the whole British nation at defiance!

My anxiety to extricate my readers and myself from these disastrous scenes prevents me from giving the whole of this gallant letter, which concluded in these manly and affectionate terms:—-

“As touching the threats in your conclusion, we have nothing to answer, only that we fear nothing but what God (who is as just as merciful) shall lay upon us; all things being in His gracious disposal, and we may as well be preserved by Him with small forces as by a great army, which makes us to wish you all happiness and prosperity, and recommend you to His protection.–My lords, your thrice humble and affectionate servant and friend,

“P. STUYVESANT.”

Thus having thrown his gauntlet, the brave Peter stuck a pair of horse-pistols in his belt, girded an immense powder-horn on his side, thrust his sound leg into a Hessian boot, and clapping his fierce little war-hat on the top of his head, paraded up and down in front of his house, determined to defend his beloved city to the last.

While all these struggles and dissentions were prevailing in the unhappy city of New Amsterdam, and while its worthy but ill-starred governor was framing the above quoted letter, the English commanders did not remain idle. They had agents secretly employed to foment the fears and clamors of the populace; and moreover circulated far and wide through the adjacent country a proclamation, repeating the terms they had already held out in their summons to surrender, at the same time beguiling the simple Nederlanders with the most crafty and conciliating professions. They promised that every man who voluntarily submitted to the authority of his British Majesty should retain peaceful possession of his house, his vrouw, and his cabbage-garden. That he should be suffered to smoke his pipe, speak Dutch, wear as many beeches as he pleased, and import bricks, tiles, and stone jugs from Holland, instead of manufacturing them on the spot. That he should on no account be compelled to learn the English language, nor eat codfish on Saturdays, nor keep accounts in any other way than by casting them up on his fingers, and chalking them down upon the crown of his hat; as is observed among the Dutch yeomanry at the present day. That every man should be allowed quietly to inherit his father’s hat, coat, shoe-buckles, pipe, and every other personal appendage; and that no man should be obliged to conform to any improvements, inventions, or any other modern innovations; but, on the contrary, should be permitted to build his house, follow his trade, manage his farm, rear his hogs, and educate his children, precisely as his ancestors had done before him from time immemorial. Finally, that he should have all the benefits of free trade, and should not be required to acknowledge any other saint in the calendar than St. Nicholas, who should thenceforward, as before, be considered the tutelar saint of the city.

These terms, as may be supposed, appeared very satisfactory to the people, who had a great disposition to enjoy their property unmolested, and a most singular aversion to engage in a contest, where they could gain little more than honor and broken heads: the first of which they held in philosophic indifference, the latter in utter detestation. By these insidious means, therefore, did the English succeed in alienating the confidence and affections of the populace from their gallant old governor, whom they considered as obstinately bent upon running them into hideous misadventures; and did not hesitate to speak their minds freely, and abuse him most heartily, behind his back.

Like as a mighty grampus, when assailed and buffeted by roaring waves and brawling surges, still keeps on an undeviating course, rising above the boisterous billows, spouting and blowing as he emerges, so did the inflexible Peter pursue, unwavering, his determined career, and rise, contemptuous, above the clamors of the rabble.

But when the British warriors found that he set their power at defiance, they despatched recruiting officers to Jamaica, and Jericho, and Nineveh, and Quag, and Patchog, and all those towns on Long Island which had been subdued of yore by Stoffel Brinkerhoff, stirring up the progeny of Preserved Fish and Determined Cock, and those other New England squatters, to assail the city of New Amsterdam by land, while the hostile ships prepared for an assault by water.

The streets of New Amsterdam now presented a scene of wild dismay and consternation. In vain did Peter Stuyvesant order the citizens to arm and assemble on the Battery. Blank terror reigned over the community. The whole party of Short Pipes in the course of a single night had changed into arrant old women–a metamorphosis only to be paralleled by the prodigies recorded by Livy as having happened at Rome at the approach of Hannibal, when statues sweated in pure affright, goats were converted into sheep, and cocks, turning into hens, ran cackling about the street.

Thus baffled in all attempts to put the city in a state of defence, blockaded from without, tormented from within, and menaced with a Yankee invasion, even the stiff-necked will of Peter Stuyvesant for once gave way, and in spite of his mighty heart, which swelled in his throat until it nearly choked him, he consented to a treaty of surrender.

Words cannot express the transports of the populace on receiving this intelligence; had they obtained a conquest over their enemies, they could not have indulged greater delight. The streets resounded with their congratulations–they extolled their governor as the father and deliverer of his country–they crowded to his house to testify their gratitude, and were ten times more noisy in their plaudits than when he returned, with victory perched upon his beaver, from the glorious capture of Fort Christina. But the indignant Peter shut his doors and windows, and took refuge in the innermost recesses of his mansion, that he might not hear the ignoble rejoicings of the rabble.

Commissioners were now appointed on both sides, and a capitulation was speedily arranged; all that was wanting to ratify it was that it should be signed by the governor. When the commissioners waited upon him for this purpose they were received with grim and bitter courtesy. His warlike accoutrements were laid aside; an old Indian night-gown was wrapped about his rugged limbs; a red nightcap overshadowed his frowning brow; an iron-grey beard of three days’ growth gave additional grimness to his visage. Thrice did he seize a worn-out stump of a pen, and essay to sign the loathsome paper; thrice did he clinch his teeth, and make a horrible countenance, as though a dose of rhubarb-senna, and ipecacuanha, had been offered to his lips. At length, dashing it from him, he seized his brass-hilted sword, and jerking it from the scabbard, swore by St. Nicholas to sooner die than yield to any power under heaven.

For two whole days did he persist in this magnanimous resolution, during which his house was besieged by the rabble, and menaces and clamorous revilings exhausted to no purpose. And now another course was adopted to soothe, if possible, his mighty ire. A procession was formed by the burgomasters and schepens, followed by the populace, to bear the capitulation in state to the governor’s dwelling. They found the castle strongly barricaded, and the old hero in full regimentals, with his cocked hat on his head, posted with a blunderbuss at the garret window.

There was something in this formidable position that struck even the ignoble vulgar with awe and admiration. The brawling multitude could not but reflect with self-abasement upon their own pusillanimous conduct, when they beheld their hardy but deserted old governor, thus faithful to his post, like a forlorn hope, and fully prepared to defend his ungrateful city to the last. These compunctions, however, were soon overwhelmed by the recurring tide of public apprehension. The populace arranged themselves before the house, taking off their hats with most respectful humility; Burgomaster Roerback, who was of that popular class of orators described by Sallust as being “talkative rather than eloquent,” stepped forth and addressed the governor in a speech of three hours’ length, detailing, in the most pathetic terms, the calamitous situation of the province, and urging him, in a constant repetition of the same arguments and words, to sign the capitulation.

The mighty Peter eyed him from his garret window in grim silence. Now and then his eye would glance over the surrounding rabble, and an indignant grin, like that of an angry mastiff, would mark his iron visage. But though a man of most undaunted mettle–though he had a heart as big as an ox, and a head that would have set adamant to scorn–yet after all he was a mere mortal. Wearied out by these repeated oppositions, and this eternal haranguing, and perceiving that unless he complied the inhabitants would follow their own inclination, or rather their fears, without waiting for his consent; or, what was still worse, the Yankees would have time to pour in their forces and claim a share in the conquest, he testily ordered them to hand up the paper. It was accordingly hoisted to him on the end of a pole, and having scrawled his hand at the bottom of it, he anathematised them all for a set of cowardly, mutinous, degenerate poltroons–threw the capitulation at their heads, slammed down the window, and was heard stumping downstairs with vehement indignation. The rabble incontinently took to their heels; even the burgomasters were not slow in evacuating the premises, fearing lest the sturdy Peter might issue from his den, and greet them with some unwelcome testimonial of his displeasure.

Within three hours after the surrender, a legion of British beef-fed warriors poured into New Amsterdam, taking possession of the fort and batteries. And now might be heard from all quarters the sound of hammers made by the old Dutch burghers, in nailing up their doors and windows, to protect their vrouws from these fierce barbarians, whom they contemplated in silent sullenness from the garret windows as they paraded through the streets.

Thus did Colonel Richard Nichols, the commander of the British forces, enter into quiet possession of the conquered realm, as locum tenens for the Duke of York. The victory was attended with no other outrage than that of changing the name of the province and its metropolis, which thenceforth were denominated New York, and so have continued to be called unto the present day. The inhabitants, according to treaty, were allowed to maintain quiet possession of their property, but so inveterately did they retain their abhorrence of the British nation that in a private meeting of the leading citizens it was unanimously determined never to ask any of their conquerors to dinner.

Irving, Knickerbocker’s, book 7

Stuyvesant’s Image

For a couple centuries, Americans’ ideas of Peter Stuyvesant were based on his portrayal in Knickerbocker’s History of New York, anonymously published by Washington Irving in 1809 as a satire on self-important histories. In 2004, Russell Shorto’s fascinating The Island at the Center of the World began to sweep away misconceptions. A few of his comments on Stuyvesant:

Now Stuyvesant could lead. He could turn his attention to matters of genuine importance. And so he did, moving with ferocious competence. Had a lesser man been given the commission to strengthen the Dutch hold on their North American territory, the English would have swept in decades sooner than they did, and the Dutch imprint on Manhattan Island would have been too faint to make a difference to history. The problems that literally surrounded the colony were considerable and they had been allowed to fester. Stuyvesant had stepped into a chess game in which his predecessor had been an inferior player who had committed his resources into one ill-conceived strike while ignoring attacks from other areas. Stuyvesant assessed the threats, ranked them in order of priority, and went to work. … – Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World

Stuvesant’s Homes

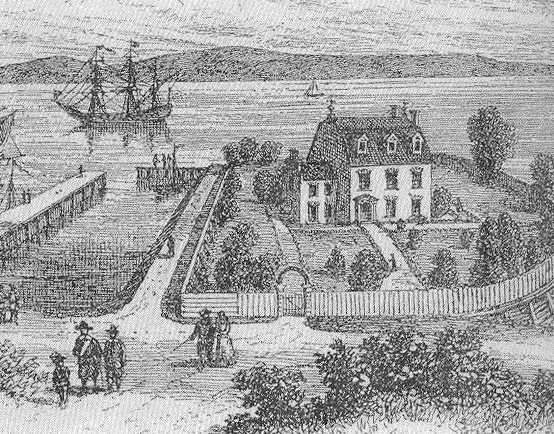

Stuyvesant’s official residence was White Hall, near the southern tip of the island at Pearl and Whitehall Streets, more or less where the Whitehall subway station (N and R trains) is.

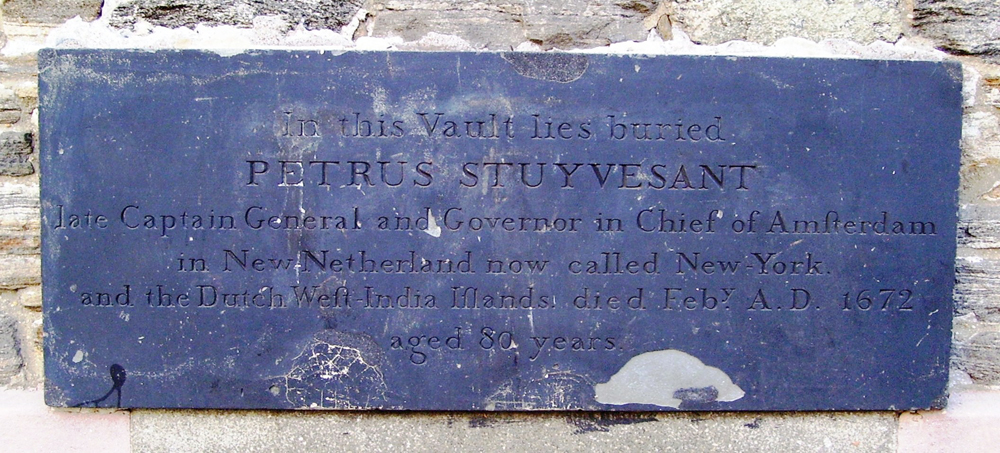

Stuyvesant’s farm, or bouwerie (after which the Bowery is named), stretched from 5th St. to 17th St. and from 4th Ave. to the East River. He’s buried at St. Mark’s in the Bowery (131 East 10th St., at Second Avenue).

Plaque over Stuyvesant’s vault at St. Mark’s. Photo: Wikipedia / Beyond My Ken

The bouwerie passed to his descendants. In 1836 Peter Gerard Stuyvesant (co-founder of the New York Historical Society and one of the richest men in America at his time) sold 4 acres of the farm to the city. In 1850 it opened as the park called Stuyvesant Square, where the sculpture of his ancestor Peter Stuyvesant now stands. The cast iron fence surrounding the park is one of the oldest in New York City.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

Whitney (1875-1942) was born into the prominent New York family founded by Cornelius Vanderbilt. She trained with James Earle Fraser (see Theodore Roosevelt) and others. Her first major commission was the Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C., 1914. During and immediately after World War I, she designed a number of memorials, including the Inwood -Washington Heights War Memorial, 1922 (Broadway and St. Nicholas Avenue, between 167th and 168th Streets).

A leading promoter of progressive American art, she was the founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art (1931), whose core collection of 500 pieces the Metropolitan Museum had refused to accept as a gift. Near the end of his life, Daniel Chester French (whose works in New York include the Continents and the Hunt Memorial) found that his studio on Eighth Street was too large for his needs. He sold it to Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who used it as the first home of the Whitney Museum. The Whitney Biennial is one of the contemporary art world’s most prestigious exhibitions.

Manhattan has Whitney’s Stuyvesant and Inwood-Washington Heights Memorial. The Bronx has the Untermeyer Memorial (Woodlawn Cemetery).

More

- Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan sets Stuyvesant’s historical context and has a long quote on him from van Loon’s classic Life and Times of Peter Stuyvesant. On Knickerbocker’s History, see Burrows & Wallace pp. 415-9. Shorto’s Island at the Center of the World is a much more balanced and modern view than Knickerbocker’s History, although it’s less likely to make you chortle.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.