Back in high school, I was taught that America’s alliance with France was crucial for winning the Revolutionary War. Today’s question: just what did the French contribute?

Back in high school, I was taught that America’s alliance with France was crucial for winning the Revolutionary War. Today’s question: just what did the French contribute?

King Louis XVI didn’t love the Americans nearly as much as he hated the British, who a decade earlier had walloped the French in the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). When the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, the French began sending supplies (mostly gunpowder) and allowing high-ranking military men to go “on leave” to advise the Americans.

What French aid cost the French king

Over the course of the Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783, the French spent 1.3 billion francs aiding the Americans. (So says Schiff, A Great Improvisation, p. 5.) This was twice the normal annual income of the French government. Rather than figuring out what this would be in 2016 currency, let’s just imagine how much deep financial trouble you or I would be in if we suddenly spent twice our annual income, and still had to cover all normal living expenses.

Coping with this debt is often cited as one of the reasons for the political and economic instability in France just before the French Revolution (1789). You could say King Louis lost his head over the debt.

The Franco-American Treaty of Alliance

On February 6, 1778, France and America signed the Treaty of Alliance, which had been negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. France and the United States were now officially military allies against Great Britain. Neither was to make a separate peace with the British, and American independence was to be a condition of any peace agreement. Since France was one of the leading nations in Europe at this time, in terms of wealth and population, this alliance was a major coup for the Americans.

France and the United States became commercial allies, too. By the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (also 2/6/1778), the two countries agreed to a number of mutual protections regarding commerce: most-favored-nation status, protection of cargoes in each others’ territories, right to due process if contraband was seized, restoration of property stolen by pirates, and so on.

The French fleet arrives

In August 1778 – six months after the Treaty of Alliance was signed – a French fleet under Admiral d’Estaing was sent to help the Americans. As it approached the British-held harbor at Newport, Rhode Island, the weather turned foul. The fleet hustled back out to sea. The Americans under General John Sullivan narrowly escaped capture by the British. Not an auspicious start for the partnership.

In September and October 1779, Admiral d’Estaing commanded a Franco-American force attacking Savannah, Georgia. He failed to capture it from the British, and was recalled to France. Not an auspicious second attempt by the partnership.

Lafayette as mediator

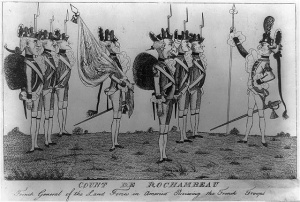

The nineteen-year-old Marquis de Lafayette arrived in America in June 1777 and fought beside Washington until late 1778. Then he sailed back to France to help persuade King Louis XVI to send troops and money. He returned to America in April 1780, just in time to serve as Washington’s liaison with Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau.

Rochambeau arrived at Newport with 5,500 men and instructions from Louis XVI to put his force at Washington’s disposal. He also brought hard currency to pay for all the French army’s needs – a boon, given the state of American currency. (See last week’s post.)

Washington, delighted to hear of the French fleet’s arrival, wrote to Rochambeau on July 16, 1780:

Sir,

I hasten to impart to you the happiness I feel at the welcome news of your arrival; and as well in the name of the American Army as in my own name to present you with an assurance, of our warmest sentiments for Allies, who have generously come to our Aid.As a citizen of the United States and as a Soldier in the cause of liberty, I thankfully acknowledge this new mark of friendship from his Most Christian Majesty—and I feel a most grateful sensibility for the flattering confidence he has been pleased to honor me with on this occasion. …

The Marquis De La Fayette has been by me desired from time to time to communicate such intelligence and make such prepositions as circumstances dictated. I think it so important immediately to fix our plan of operations and with as much secrecy as possible, that I have requested him to go himself to New London, where he will probably meet you. As a Genl Officer I have the greatest confidence in him—as a friend he is perfectly acquainted with my sentiments & opinions—He knows all the circumstances of our Army & the Country at large; All the information he gives and all the propositions he makes, I entreat you will consider as coming from me. I request you will settle all arrangements whatsoever with him …. (Whole letter here)

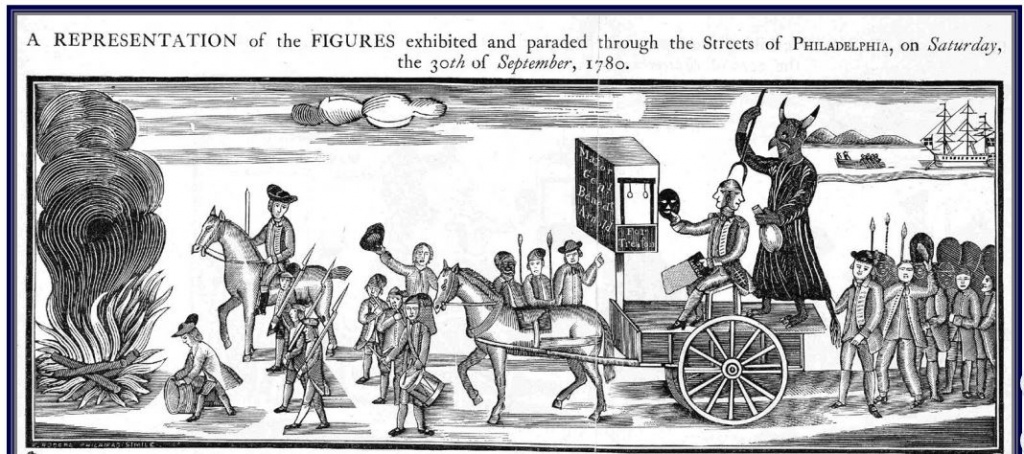

Despite their mutual regard, Washington and Rochambeau’s relationship had its glitches. In September 1780, Washington felt he had to comment on the shocking treason of General Benedict Arnold, who had planned to hand the fortifications at West Point – along with Commander-in-Chief Washington and General Lafayette – over to the British.

Sir

On my arrival here a very disagreeable scene unfolded itself. By a lucky accident a conspiracy of the most dangerous kind the object of which was to sacrifice this post. has been detected. General Arnold, who has sullied his former glory by the blackest treason, has escaped to the enemy. This is an event that occasions me equal regret and mortification; but traitors are the growth of every country and in a revolution of the present nature it is more to be wondered at, that the catalogue is so small than that there have been found a few. (9/26/1780; whole letter here)

In March 1781, Arnold – now a brigadier-general in the British army – was rampaging through Virginia. Lafayette was sent with several thousand American soldiers to harass him. The Chevalier Destouches, in Rhode Island, dispatched a few ships from the French fleet to Virginia. They were too few to trap Arnold. Crippled by gout (serve him right!), Arnold returned to New York, the British headquarters in America.

In a personal letter to his estate manager, Lund Washington, George Washington complained that those French ships had been far too few and far too late. The letter was waylaid by the British and published in the New-York Gazette.

I haven’t been able to find the Gazette’s version … but I suspect it sounded something like these comments by Washington to John Laurens (4/9/1781), who was still serving as American envoy in Paris.

[T]he Chevr Destouches had sent a Ship of the line and two or three frigates to Chesapeak bay which not only retarded the plan I had proposd (by awaiting their return) but, ultimately, defeated the project, as the enemy in the meantime remasted the Bedford with those taken out of the Culloden & following the French fleet, arrived off the Capes of Virginia before it—where a Naval combat glorious for the French (who were inferior in Ships and Guns) but unprofitable for us who were disappointed of our object was the issue.

The failure of this Expedition, (which was most flattering in the commencement of it) is much to be regretted; because a successful blow in that quarter, would, in all probability, have given a decisive turn to our Affairs in all the Southern States—Because it has been attended with considerable expence on our part, & much inconvenience to the State of Virginia, by assembling its Militia—And because the World are disappointed at not seeing Arnold in Gibbets. above all, because we stood in need of something to keep us a float, till the result of your mission is known for be assured my dear Laurens, that day does not follow night more certainly than it brings with it some additional proof of the impracticality of carrying on the War without the aids you were directed to sollicit. (Whole letter here)

Washington’s intercepted letter, as printed in the Gazette, was brought to Rochambeau’s attention. Rochambeau repeated the part he found most disturbing, but kept his temper admirably:

Newport, April 26th, 1781

Sir,

The New-york Gazette has published a Supposed intercepted Letter wrote, as it says by your Excellency to Mr Land Washington, and in which is this Paragraph. “It is very unlikely [NOTE: for “unfortunate”?], I say it to you in confidence that the French fleet and detachment did not undertake this present expedition at the time I proposed it. The destruction of Arnold’s corps would have been unavoidable, and over before the British squadron could have put to sea: Instead of this, they have sent the small squadron that took the Romulus and some other vessels, But as I had foreseen it, it could do nothing at Portsmouth, without the help of some Land Troops.”If really this Letter has been wrote by Your Excellency, I shall beg Leave to observe, that the result of this reflexion should seem to be, that We have had here the choice of two expeditions proposed, and that We have preferred the Least to a more considerable undertaking which your Excellency desired. … I hope that your Excellency is fully persuaded that the King having put me under your orders, I shall always follow them with as much exactness as any General Officer of your Excellency’s army, being bound to do so as much by my inclination as my duty. … (Whole letter here)

To Lafayette, his most trusted liaison with the French, Washington wrote on 4/22/1781:

I am very sorry that any letter of mine should be the subject of public discussion, or give the smallest uneasiness to any person living—The letter, to which I presume you allude, was a confidential one from me to Mr Lund Washington (with whom I have lived in perfect intimacy for near 20 Years)—I can neither avow the letter as it is published by Mr Rivington, nor declare that it is spurious, because my letter to this Gentn was wrote in great haste, and no copy of it was taken—all I remember of the matter is, that at the time of writing it, I was a good deal chagreened to find by your letter of the 15th of March (from York Town in Virginia) that the French fleet had not, at that time, appeared within the Capes of Chesapeak; and meant (in strict confidence) to express my apprehensions and concern for the delay; but as we know that the alteration of a single word does often times, pervert the Sense, or give force to expression unintended by the letter writer, I should not be surprized at Mr Rivingtons or the Inspector of his Gazette having taken this liberty with the letter in question; especially as he, or they have, I am told, lately published a letter from me to Govr Hancock and his answer, which never had an existance but in the Gazette. That the enemy fabricated a number of Letters for me formerly, is a fact well known—that they are not less capable of doing it now few will deny. as to his asserting, that this is a genuine copy of the original—he well knows that their friends do not want to convict him of a falsehood and that ours have not the oppertunity of doing it, though both sides are knowing to his talents for lying.

In the next paragraph is one of Washington’s few references to Alexander Hamilton’s resignation from his staff.

The event, which you seem to speak of with regret, my friendship for you would most assuredly have induced me to impart to you in the moment it happened had it not been for the request of H—— who desired that no mention might be made of it: Why this injunction on me, while he was communicating it himself, is a little extraordinary! but I complied, & religiously fulfilled it. With every sentiment of Affecte regard I am Yrs

Go: Washington (Whole letter here)

Rendezvous with Rochambeau

By May 1781, the options for a joint Franco-American attack had been reduced to New York or Virginia, where Lafayette (with some 4,500 men) was harassing Lord Cornwallis. Cornwallis, who answered only to Sir Henry Clinton at British headquarters in New York, was in command of some 8,000 troops.

In August, when word arrived that a French fleet under Admiral De Grasse would be available for joint operations in the southern states from September until mid-October, the decision was made. Virginia would be the target.

The French troops marched south from Newport, meeting Washington’s army in August at Philipsburg, New York. From there, they continued south in separate columns spread out over a considerable distance, to make gathering provisions on the march easier – and to confuse the British about the army’s size and destination. In Maryland, many of the troops embarked on transports to carry them to the Virginia Peninsula, where Cornwallis had hunkered down at Yorktown.

Of this 500-mile odyssey, one German serving under the French wrote home:

I hope that you have received my last letter that I had the honor to write to you while passing through Philadelphia. Since then we have traveled through a lot of country with the American army and been subjected to a lot of fatigues …

The campaign has been pretty hard on us, but in return I had the satisfaction of seeing a large part of the country. Here are the names of the provinces I marched through between 2 June and September 29. We stopped at Philippsburg for 15 days, which is in the province of New York, to rest up; Rhod Island, Connecticut, Jork Statt, Jersey, Pinsilvani, Mariland, Virgini. Judge for yourself, my very dear uncle, that we were exhausted and desirous to go into winter quarters. (Wilhelm Graf von Schwerin; quoted here)

Winter quarters: Not … yet.

Hamilton gets a command

Alexander Hamilton finally received his longed-for field command on July 31, 1781. At that point, the objective of the Franco-American army had not yet been decided, but within a month he knew where he was headed.

Haverstraw [New York] Aug 22d. 81

In my last letter My Dearest Angel I informed you that there was a greater prospect of activity now than there had been heretofore. I did this to prepare your mind for an event which I am sure will give you pain. I begged your father at the same time to intimate to you by degrees the probability of its taking place. I used this method to prevent a surprise which might be too severe to you. A part of the army My Dear girl is going to Virginia, and I must of necessity be separated at a much greater distance from my beloved wife. I cannot announce the fatal necessity without feeling every thing that a fond husband can feel. I am unhappy my Betsey. I am unhappy beyond expression, I am unhappy because I am to be so remote from you, because I am to hear from you less frequently than I have been accustomed to do. I am miserable because I know my Betsey will be so. I am wretched at the idea of flying so far from you without a single hour’s interview to tell you all my pains and all my love. But I cannot ask permission to visit you. It might be thought improper to leave my corps at such a time and upon such an occasion. I cannot persuade myself to ask a favour at Head Quarters. I must go without seeing you. I must go without embracing you. Alas I must go.

But let no idea other than of the distance we shall be asunder disquiet you. Though I said the prospects of activity will be greater, I said it to give your expectation a different turn and prepare you for something disagreeable. It is ten to one that our views will be disappointed by Cornwallis retiring to South Carolina by land. At all events our operations must be over by the latter end of October and I will fly to the arms of my Betsey.

Let me implore you my Dear My amiable wife, let not the length of absence or the distance of situation steal from me one particle of your tenderness. It is the only treasure I possess in this world. I shall loath existence if it should be lost or even impaired. A miser is greedy of his gold, but the comparison would be cold and poor to say I am more greedy of your love. It is the food of my hopes, the object of my wishes, the only enjoyment of my life. Neither time distance nor any other circumstance can abate that pure that holy that ardent flame which burns in my bosom for the best and sweetest of her sex. Oh heaven shield and support her. Bring us speedily together again & let us never more be separated

Adieu Adieu My Betsey

A HamiltonI have had too little time to write this. I will write you again at large this day. Dont mention ⟨I am⟩ going to Virgin⟨ia⟩ (Whole letter here)

Next week: what’s the big deal about Redoubt 10? And why did they take the bullets out of their guns?

More

- Read more about Rochambeau and Washington on the sites of the National Park Service, the Museum of the American Revolution, and Xenophon Group. Most of the numbers and dates above are from one or the other of those articles.

- I’ve started adding comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical: a fantastic resource. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the thirtieth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. My intro to this series is here. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.