New York is the greatest city in the world: no argument from me about that. But greatness has to start somewhere …

New York is the greatest city in the world: no argument from me about that. But greatness has to start somewhere …

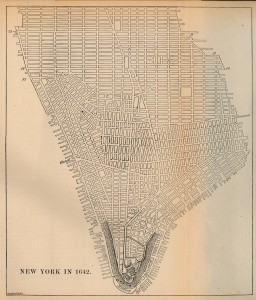

Here’s the Dutch settlement at the southern end of Manhattan in 1642 – just before Peter Stuyvesant was sent by the West India Company to manage New Netherland. The Dutch colony stretched from Schenectady to the southern end of Delaware, with its headquarters at New Amsterdam.

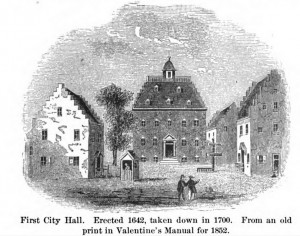

The image below shows what seems to have been the grandest building in the city during the 17th century. According to Shorto, it was the City Tavern until 1653, when the town was granted a municipal government. At that point it became City Hall. (There’s a joke there somewhere.) Shorto says the pavement at Pearl Street and Coenties Slip has an outline of the building, which is now on my must-stand-there list.

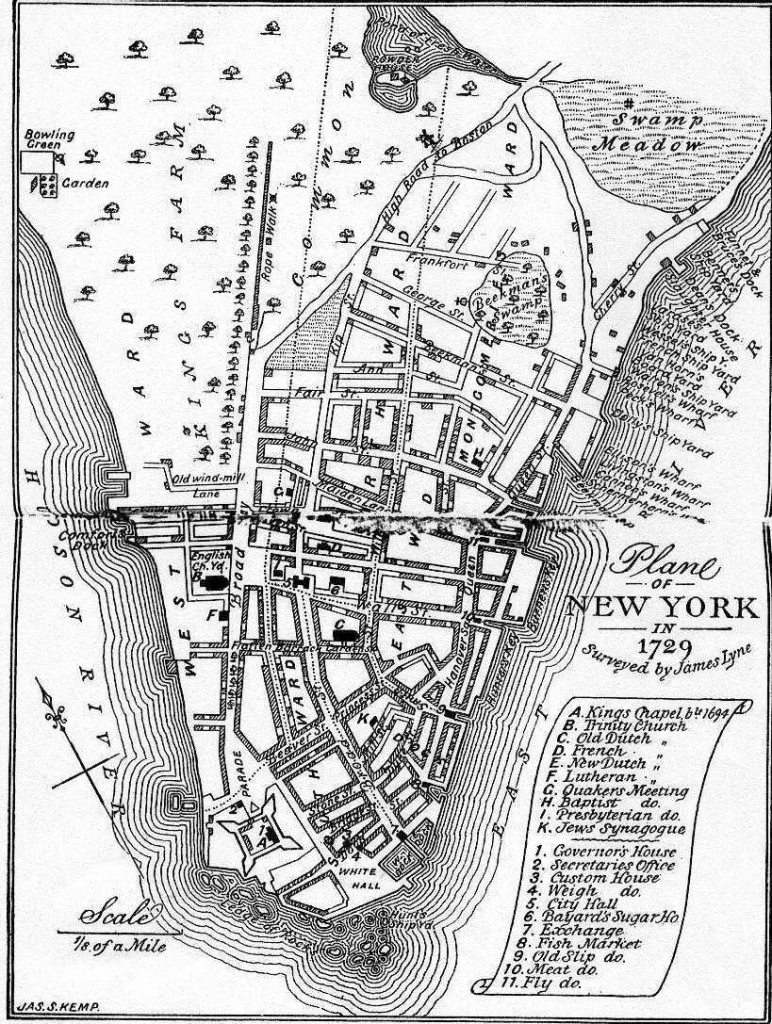

In the map below, you can see the Fort Amsterdam at the south end of Manhattan, which looks impressive.

Not so much. When four British men-of-war sailed into the harbor in 1664 to grab the island for King Charles II, Peter Stuyvesant wrote to his employers:

We have no soldiers, we have no gunpowder, we are short of food. Furthermore the citizens are completely disheartened. They cannot see that there is the slightest chance of relief in the case of a siege, and if the island falls into the hands of the invaders, they fear for the lives of themselves and their wives and their children.. It is clearly apparent that this town cannot possibly hope to hold out for more than a very few days.

The letter never reached the West India Company: no Dutch ship managed to evade the British men-of-war. Here’s the town just before it was surrendered to the British.

New Amsterdam became New York. Fort Amsterdam became Fort George, and the area under its battery of guns became … Well, you can guess.

On the 1729 map below – when the British had been in control for six decades – the town has grown, but you’re still in the country by the time you reach the pond that became the site of the notorious Five Points (Canal / Centre / Bowery / Park Row). Queen Street, where Hercules Mulligan eventually had his tailor shop, is near the river on the east side.

Below is a view of New York a dozen years before the Revolution – 1764, the year between the end of the French and Indian War and the passage of the much-resented Quartering Act and Stamp Act. Fort George is front and center, flying an British flag of extraordinary dimensions.

Revolution in New York

In April 1775, Americans clashed with British troops at Lexington and Concord, in Massachusetts. Two months later, Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army and Boston was besieged. Boston’s situation provoked many New Yorkers to flee their city for fear of similar reprisals. By mid-1776, when the British fleet sailed into New York Harbor, the city’s population is estimated to have plummeted from about 20,000 to about 5,000.

In September – a week after the Continental Army fled and the British occupied the city – a devastating fire ripped north from the Battery. It destroyed some 500 buildings, probably a third of the city’s total. As the British searched for arsonists, Nathan Hale was hauled in as a suspicious character, and hanged as a spy the following day.

The red area on the map below marks the fire damage.

Nothing was done to repair this damage during the British occupation: soldiers have other priorities.

A sensible person would end this post here … what the hell.

Here’s a selection of the few Revolutionary War-era buildings in Manhattan that are still standing, or have been more-or-less-faithfully reconstructed – working south to north.

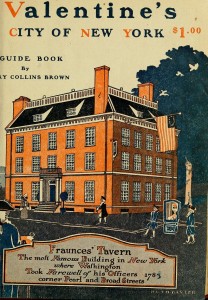

1. Fraunces Tavern

On November 25, 1783, General George Washington rode down Broadway to reclaim the city after the British finally evacuated it. (Pics here.) Then he visited tailor and ex-spy Hercules Mulligan. For the next ten days Washington resided at Fraunces Tavern (54 Pearl St., near Broad), where he held a farewell dinner on December 4 for his officers.

The Tavern was built in 1719. What stands on the site now is, according to the AIA Guide to New York City, “a highly conjectural construction – not a restoration – based on ‘typical’ buildings of ‘the period,’ parts of remaining walls, and a lot of guesswork” (p. 15 in the 4th ed.). Today the building contains an upscale restaurant and a gift shop.

2. Trinity Church

Alexander and Eliza were members of Trinity Church, on Broadway at Wall Street, whose current home dates to 1839. Trinity was one of the hundreds of buildings lost during the Great Fire of September 1776. St Paul’s Chapel (209 Broadway, at Fulton) was just barely outside the conflagration. Its construction date of 1766 makes it the oldest church standing in Manhattan.

At the entrance to St Paul’s is a memorial to General Richard Montgomery, who died in 1775 during the American invasion of Canada. (Yes, we did.) Philip Schuyler was nominally in command of that invasion, and Aaron Burr served under Montgomery. Inside St Paul’s, beneath the Great Seal of the United States, is the pew where President George Washington sat when he attended services in New York.

3. The Liberty Pole

If you stand on the west side of City Hall and crane your eyes skyward, you’ll see a flagpole that bears at its top a gilded plaque with the word “Liberty.” In April 1766, when the Stamp Act was repealed, the colonists believed it was due to the efforts of King George III. Grateful New Yorkers commissioned a gilded statue of him for Bowling Green – and a crowd of rowdy patriots stuck a pine tree on the northwestern corner of the Commons (now City Hall Park), proclaiming it a liberty pole. It bore a sign reading “George III, Pitt and Liberty.” On the one-year anniversary of the repeal, British regulars hacked down the tree. The Sons of Liberty raised another the very next day, axe-proofing it with iron bands. British soldiers knocked it down. Two days later the Sons of Liberty set up a third pole, and refused to let the British soldiers patrol or drill. George III told the governor of New York to refuse to sign any legislation passed by the Assembly until New Yorkers became properly submissive subjects again. (See Ellis, pp. 150-1.) The current pole dates to 1921.

4. Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument

The massively destructive fire of 1776 resulted in a shortage of buildings to house citizens and troops. When American prisoners-of-war from the Battle of Long Island and the Battle of Fort Washington were brought to Manhattan, they were shoved by the hundreds into large, sturdy, but unaccommodating buildings such as sugar warehouses. A window from the Rhinelander Sugar Factory is preserved near One Police Plaza. It’s Revolutionary War vintage, but the prisoners were probably kept in a warehouse owned by the Livingstons. See the Daytonian in Manhattan for a thorough discussion with lots of pics.

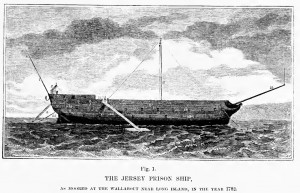

Washington did not make a practice of prisoner exchanges: well-trained British soldiers returned to their units would have been sent back out to capture or kill more Americans. So the number of prisoners in New York – which was the British army’s headquarters in the colonies – continually grew. Eventually many of these prisoners were shifted out of Manhattan, locked up in prison hulks in Wallabout Bay. That’s on the Brooklyn shore between where the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges now stand.

During the course of the Revolution, some 6,800 American soldiers died in battle. It’s estimated that 11,000 died as prisoners of war in New York. The Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument in Fort Greene is a belated tribute to them.

5. Morris-Jumel Mansion

The Morris-Jumel Mansion (65 Jumel Terrace, near Sylvan Terrace, at about 161st St.) is Manhattan’s oldest house, built in 1765. During the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776 it was Washington’s headquarters. In 1790, as president, he held a dinner there whose guests included John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton. Aaron Burr later married the woman who owned it.

6. Reconstruction of Hessian huts

You’d be surprised what obscure places you find when you homeschool a kid in New York. So:

The Dyckman family returned to Manhattan in 1783 to find that the British had burned down their farmhouse. In 1785, they rebuilt nearby, at what’s now 4881 Broadway (204th St.). Dyckman House is the oldest farmhouse standing in Manhattan; but then, there’s not much competition in that category, is there? When the farmhouse was being restored in the early 20th century, excavation of the area around it turned up the foundations of 60 huts that had housed Hessian mercenaries during the Revolutionary War. One “Hessian hut” was rebuilt. See the excellent Dayton in Manhattan post on the farmhouse and the hut.

Most American soldiers would have considered these luxury accommodations.

Upward mobility in New York

Russell Shorto argues New York became a place where anyone could rise above his station because of a unique combination of Dutch and English ideas. In 1653, the States General of Holland granted New Amsterdam a municipal government, in reaction to the Remonstrance of Adriaen van der Donck (an amazing character). Men could become citizens as “small burghers” – they could even pay the 18-stiver fee for that status in installments (forms here). As they prospered, they could rise to the status of great burgher (fee of 3 guilders), which gave them a voice in setting policy. That sort of social mobility wasn’t common in Europe. Nor was the tolerance for different races and creeds that was practiced in this out-of-the-way trading post.

In 1664, the name of the town changed from New Amsterdam to New York. But the people were the same. By the Articles of Capitulation that were signed when the British took over, the traders stayed put, and their systems of government and business remained intact. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: as Shorto points out, the melting pot that was New Amsterdam was turning a nice profit, and that’s why the British wanted to control it.

The English who came to New York in the 17th and early 18th centuries brought with them a firm conviction in individual rights (life, liberty, property), based largely on the writings of John Locke. Together, individual rights and social mobility made for a place where anyone could remake himself into a new and better man.

More

- This interview with historian David McCullough about New York during the Revolutionary War is fascinating.

- Russell Shorto’s Island at the Center of the World did for the Dutch settlement on Manhattan almost as much as Hamilton: An American Musical did for Alexander Hamilton. My favorite survey of the history of New York up to the 1960s is Edward Robb Ellis’s The Epic of New York City. Burrows & Wallace’s Gotham: A History of New York to 1898 has has a jaw-dropping depth of research, but it’s an extremely long, dense read; I prefer my history more narrative than statistical.

- The Grange wasn’t built until 1802, silly. See this earlier post.

- If you want to visit the sculptures of all the Founding Fathers that stand in Manhattan (plus others figures who date before 1800), a handy list is here.

- I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the thirteenth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.