“Employ all your leisure in reading”

“Employ all your leisure in reading”

By early July 1780, Alexander and Eliza had been engaged for several months. (For Alexander’s list of requirements for a wife, his letter to sister Peggy about Eliza, and Papa Schuyler’s permission to marry, see last week’s post.) Since February, Eliza had been staying in Morristown with Dr. Cochran, George Washington’s personal physician. When the army left winter quarters, she set out for her parents’ home in Albany – and then we have letters from Alexander to her.

In the letter below, Alexander reminds Eliza of her promise to read widely so that they can have long talks about important subjects. It’s exactly the same attitude he showed to Kitty Livingston back in 1777, when he was a carefree bachelor: he’s willing, even eager, to talk with women as equals, on politics and other matters.

[Preakness, New Jersey, July 2–4, 1780]

I have been wishing my love for an opportunity of writing to you, but none has offered. The inclosed [see below] was sent to you at Morris Town, but missed you; as it contains ideas that often occur to me, I send it now. Last evening Doctor Cochran delivered me the dear lines you wrote me from Nicholson’s. I shall impatiently long to hear of your arrival at Albany and the state of your health. I am perfectly well, proof against any thing that can assail mine. We have no change in our affairs since you left us. I should regret the time already lost in inactivity if it did not bring us nearer to that sweet reunion for which we so ardently wish. I never look forward to that period without sensations I cannot describe.

I love you more and more every hour. The sweet softness and delicacy of your mind and manners, the elevation of your sentiments, the real goodness of your heart, its tenderness to me, the beauties of your face and person, your unpretending good sense and that innocent simplicity and frankness which pervade your actions; all these appear to me with increasing amiableness and place you in my estimation above all the rest of your sex.

I entreat you my Charmer, not to neglect the charges I gave you particularly that of taking care of your self, and that of employing all your leisure in reading. Nature has been very kind to you; do not neglect to cultivate her gifts and to enable yourself to make the distinguished figure in all respects to which you are intitled to aspire. You excel most of your sex in all the amiable qualities; endeavour to excel them equally in the splendid ones. You can do it if you please and I shall take pride in it. It will be a fund too, to diversify our enjoyments and amusements and fill all our moments to advantage.

I have received a letter from my Laurens [who had been captured by the British and was released on parole in Pennsylvania] solicitg an interview on the Pensylvania Boundary. The General has half consented to its taking place. I hope to be permitted to meet him; if so, I will go to Philadelphia and then you may depend, I shall not forget the picture you requested.

Yrs. my Angel with inviolable Affection

Alex Hamilton

July 2d. 80

It is now the fourth and no opportunity has offered. I open my letter just to tell you your Papa has been unwell with a touch of the Quinsey; but is now almost perfectly recovered. He hoped to be at Hd. Qrs. to day. He is eight miles off. I saw him last evening and heard from him this morning. I mention this lest you should hear of his indisposition through an exaggerated channel and be unnecessarily alarmed. Affectionately present me to yr Mama.

Adieu my love (Whole letter here)

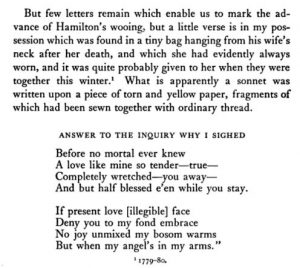

The “inclosed” that Alexander refers to above may be the poem that Allan McLane Hamilton reported was written on a slip of paper that Eliza treasured:

From Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, 1910, p. 126.

“Do you soberly relish the pleasure of being a poor mans wife?”

A month after the letter above, Alexander wrote to Eliza. Main points: 1) Please write me! And let’s number our letters so we know if we miss any. 2) I’ll quit the army if you ask me to, but please don’t. 3) Here’s the state of the war. 4) I don’t have a fortune: can you handle that?

[Teaneck, New Jersey, August, 1 1780]

Impatiently My Dearest have I been expecting the return of your father to bring me a letter from my charmer with the answers you have been good enough to promise me to the little questions asked in mine by him. I long to see the workings of my Betseys heart, and I promise my self I shall have ample gratification to my fondness in the sweet familiarity of her pen. She will there I hope paint me her feelings without reserve—even in those tender moments of pillowed retirement, when her soul abstracted from every other object, delivers itself up to Love and to me—yet with all that delicacy which suits the purity of her mind and which is so conspicuous in whatever she does.

It is now a week my Betsey since I have heard from you. In that time I have written you twice. I think it will be adviseable in future to number our letters, for I have reason to suspect they do not all meet with fair play. This is number one.

[Richard Kidder] Meade just comes in and interrupts me by sending his love to you. He tells you he has written a long letter to his widow asking her opinion of the propriety of quitting the service; and that if she does not disapprove it, he will certainly take his final leave after the campaign. You see what a fine opportunity she has to be enrolled in the catalogue of heroines, and I dare say she will set you an example of fortitude and patriotism. I know too you have so much of the Portia in you, that you will not be out done in this line by any of your sex, and that if you saw me inclined to quit the service of your country, you would dissuade me from it. I have promised you, you recollect, to conform to your wishes, and I persist in this intention. It remains with you to show whether you are a Roman or an American wife. [NOTE: He’s probably referring to Portia, the steadfast wife of Brutus, who is described in Plutarch’s Life of Brutus – rather than Portia in the Merchant of Venice.]

Though I am not sanguine in expecting it, I am not without hopes this Winter will produce a peace and then you must submit to the mortification of enjoying more domestic happiness and less fame. This I know you will not like, but we cannot always have things as we wish.

The affairs of England are in so bad a plight that if no fortunate events attend her this campaign, it would seem impossible for her to proceed in the war. But she is an obstinate old dame, and seems determined to ruin her whole family, rather than to let Miss America go on flirting it with her new lovers, with whom, as giddy young girls often do, she eloped in contempt of her mothers authority. I know you will be ready to justify her conduct and to tell me the ill treatment she received was enough to make any girl of spirit act in the same manner. But I will one day cure you of these refractory notions about the right of resistance, (of which I foresee you will be apt to make a very dangerous application), and teach you the great advantage and absolute necessity of implicit obedience.

But now we are talking of times to come, tell me my pretty damsel have you made up your mind upon the subject of housekeeping? Do you soberly relish the pleasure of being a poor mans wife? Have you learned to think a home spun preferable to a brocade and the rumbling of a waggon wheel to the musical rattling of a coach and six? Will you be able to see with perfect composure your old acquaintances flaunting it in gay life, tripping it along in elegance and splendor, while you hold an humble station and have no other enjoyments than the sober comforts of a good wife? Can you in short be an Aquileia and chearfully plant turnips with me, if fortune should so order it? If you cannot my Dear we are playing a comedy of all in the wrong, and you should correct the mistake before we begin to act the tragedy of the unhappy couple. [NOTE: I can’t sort out who Aquileia is, but among the Romans, turnips where the cheapest and most rustic food known.]

I propose you a set of new questions my lovely girl; but though they are asked with an air of levity, they merit a very serious consideration, for on their being resolved in the affirmative stripped of all the colorings of a fond imagination our happiness may absolutely depend. I have not concealed my circumstances from my Betsey; they are far from splendid; they may possibly even be worse than I expect, for every day brings me fresh proof of the knavery of those to whom my little affairs are entrusted. They have already filed down what was in their hands more than one half, and I am told they go on diminishing it, ’till I fear they will reduce it below my former fears. [NOTE: He’s talking about the subscription set up for him by the citizens of St. Croix, after the “hurricane letter.”] An indifference to property enters into my character too much, and what affects me now as my Betsey is concerned in it, I should have laughed at or not thought of at all a year ago. But I have thoroughly examined my own heart. Beloved by you, I can be happy in any situation, and can struggle with every embarrassment of fortune with patience and firmness. I cannot however forbear entreating you to realize our union on the dark side and satisfy, without deceiving yourself, how far your affection for me can make you happy in a privation of those elegancies to which you have been accustomed. If fortune should smile upon us, it will do us no harm to have been prepared for adversity; if she frowns upon us, by being prepared, we shall encounter it without the chagrin of disappointment. Your future rank in life is a perfect lottery; you may move in an exalted you may move in a very humble sphere; the last is most probable; examine well your heart. And in doing it, dont figure to yourself a cottage in romance, with the spontaneous bounties of nature courting you to enjoyment. Dont imagine yourself a shepherdess, your hair embroidered with flowers a crook in your hand tending your flock under a shady tree, by the side of a cool fountain, your faithful shepherd sitting near and entertaining you with gentle tales of love. These are pretty dreams and very apt to enter into the heads of lovers when they think of a connection without the advantages of fortune. But they must not be indulged. You must apply your situation to real life, and think how you should feel in scenes of which you may find examples every day. So far My Dear Betsey as the tenderest affection can compensate for other inconveniences in making your estimate, you cannot give too large a credit for this article. My heart overflows with every thing for you, that admiration, esteem and love can inspire. I would this moment give the world to be near you only to kiss your sweet hand. Believe what I say to be truth and imagine what are my feelings when I say it. Let it awake your sympathy and let our hearts melt in a prayer to be soon united, never more to be separated.

Adieu loveliest of your sex

AH

Instead of inclosing your letter to your father I inclose his to you because I do not know whether he may not be on his way here. If he is at home he will tell you the military news. If he has set out for camp, you may open and read my letters to him. The one from Mr. Mathews [delegate to Congress from South Carolina] you will return by the first opportunity. (Whole letter here; also Library of America, pp. 66-9)

“All the proofs I have of your tenderness and readiness to share every kind of fortune”

The main points: 1) I’m very sorry if I insulted you by asking whether you could bear to live in poverty: it’s because I don’t have a high opinion of most men and women. 2) Everyone at camp has fallen in love with the same cute girl, but she has no soul, so she doesn’t tempt me.

[Liberty Pole, New Jersey, September 3, 1780]

I wrote you last night the inclosed hasty note in expectation that your papa would take his leave of us this morning early; a violent storm in which our house is tumbling about our ears prevents him. He and Meade are propping the house (I mean the Marquis), and I sit down to indulge the pleasure I always feel in writing to you.

The little song you sent me I have read over and over. It is very pretty and contains precisely those sentiments I would wish my betsey to feel, and she tells me it is an exact copy of her heart. [NOTE: We don’t have that letter.] You seem by sympathy to have anticipated the inquiries I made in one of mine lately, and to have answered them all by this little song; a pretty method indeed when I am asking a set of sober questions, of the greatest importance, to answer me with a song. I confess however that they scarcely deserved a better and that if you should in reality refer me to your song, I shall be very well served. For after all the proofs I have of your tenderness and readiness to share every kind of fortune with me it is a presumptuous diffidence of your heart to propose the examination I did. But be assured My angel it is not a diffidence of my betsey’s heart, but of a female heart, that dictated the questions. I am ready to believe everything in favour of yours; but am restrained by the experience I have had of human nature, and of the softer part of it. Some of your sex possess every requisite to please delight, and inspire esteem friendship and affection; but there are too few of this description. We are full of vices. They are full of weaknesses; though I will not agree with the poet that they are, “Matter too soft, a lasting mark to bear. And best distinguished by black brown or fair.” Nor will I join in the exclamation of Adam against the Creators having formed woman, “a fair defect of nature.” Yet I have reason to think that these portraits are applicable to too many of the sex; and though I am satisfied, whenever I trust my senses and my judgment that you are one of the exceptions, I cannot forbear having moments when I feel a disposition to make a more perfect discovery of your temper, and character. In one of those moments I wrote the letter in question.

Do not however I entreat you suppose that I entertain an ill opinion of all your sex. I have a much worse of my own. I have seen more of yours that merited esteem and love, but the truth is, My Dear girl, there are very few of either that are not very worthless. You know my sentiments on this head. I think I have found a precious jewel. I pray you do not think your sex injured and undertake to be their champion; for it will be taking an unfair advantage of your influence over me.

We have been fortunate of late in Quarters. I gave you a description of a fair one in those we had at Tappan. We have found another here; a pretty little dutch girl of fifteen. Every body make⟨s⟩ love to her, and she receives every body kindly. She grants every thing that is asked and has too much simplicity to refuse any thing; but she has so much innocence to shield her, that the most determined rake would not dare to take advantage of her simplicity. This you will say is a very favourable character; but I have summed up all her excellencies—beauty, innocence, youth, simplicity. If all her sex were like her, I would become a disciple of Mahomet. I am persuaded she has no soul; and as I am squeamish enough to require a soul in a woman, I run no great risk of becoming one of her captives.

You see I give you an account of all the pretty females I meet with; you tell me nothing of the pretty fellows you see. I suppose you will pretend there is none of them engages the least of your attention, but you know I have been told you were something of a coquette, and I shall take care what degree of credit, I give to this pretence. When your sister returns home, I shall try to get her in my interest and make her tell me of all your flirtations. Have you heard any thing more of what I hinted to you about [François Louis Teisseydre, Marquis de] Fleury? When she returns, give my love to her and tell her, I expected, she would have outstripped you in the Hymenial line.

Adieu My love

A Hamilton [Whole letter here]

“What have we to do with any thing but love?”

Main points: 1) Why don’t you write me? 2) Here’s the military news. 3) We need a new form of government. 4) I’ve given up the idea of suicide if we lose this war, but how would you feel about moving to Switzerland?

[Bergen County, New Jersey, September 6, 1780]

I wrote you My Dear Betsey a long letter or rather two long letters by your father. I have not since received any of yours. I hope I shall not be much longer without thus enjoying this only privilege of our separation. [The Founders Archive notes: “The remainder of this paragraph, consisting of fourteen lines, has been crossed out in such a way that it is impossible to decipher the writing. These lines were presumably crossed out by J. C. Hamilton.”]

Most people here are groaning under a very disagreeable piece of intelligence just come from the Southward; that Gates has had a total defeat near Cambden in South Carolina. Cornwallis and he met in the night of the 15th. by accident marching to the same point. The advanced guards skirmished and the two armies halted and formed ’till morning. In the morning a battle ensued, in which the Militia and Gates with them immediately run away and left the Continental troops to contend with the enemy’s whole force. They did it obstinately, and probably are most of them cut off. Gates however who writes to Congress seems to know very little what has become of his army. He showed that age and the long labors and fatigues of a military life had not in the least impaired his activity; for in three days and a half, he reached Hills borough, one hundred and eighty miles from the scene of action, leaving all his troops to take care of themselves, and get out of the scrape as well as they could. He has confirmed in this instance the opinion I always had of him.

This event will have very serious consequences to the Southward. Peoples imaginations have already given up North Carolina and Virginia; but I do not believe either of them will fall. I am certain Virginia cannot. This misfortune affects me less than others, because it is not in my temper to repine at evils that are past, but to endeavour to draw good out of them, and because I think our safety depends on a total change of system, and this change of system will only be produced by misfortune.

Pardon me my love for talking politics to you. What have we to do with any thing but love? Go the world as it will, in each others arms we cannot but be happy. If America were lost we should be happy in some other clime more favourable to human rights. What think you of Geneva as a retreat? ’Tis a charming place; where nature and society are in their greatest perfection. I was once determined to let my existence and American liberty end together. My Betsey has given me a motive to outlive my pride, I had almost said my honor; but America must not be witness to my disgrace. As it is always well to be prepared for the worst, I talk to you in this strain; not that I think it probable we shall fail in the contest; for notwithstanding all our perplexities, I think the chances are without comparison in our favour; and that my Aquileia and I will plant our turnips in her native land. [NOTE: Again with the cheap veggies!]

Adieu my lovely girl

A Hamilton (Whole letter here)

“I shall never make you blush”

In a letter of 9/25/1780, after telling Eliza of Benedict Arnold’s treachery and Arnold’s wife’s distraught behavior, Alexander writes:

Could I forgive Arnold for sacrificing his honor reputation and duty I could not forgive him for acting a part that must have forfieted the esteem of so fine a woman. At present she almost forgets his crime in his misfortune, and her horror at the guilt of the traitor is lost in her love of the man. But a virtuous mind cannot long esteem a base one, and time will make her despise, if it cannot make her hate.

Indeed my angelic Betsey, I would not for the world do any thing that would hazard your esteem. ‘Tis to me a jewel of inestimable price & I think you may rely I shall never make you blush.

Thank you for all the goodness of which your letters are expressive, and I entreat you my lovely girl to believe that my tenderness for you every day increases and that no time or circumstances can abate it. I quarrel wit the hours that they do not fly more rapidly and give us to each other. [More here]

“I know I have talents and a good heart; but why am I not handsome?”

Main points: 1) Here’s the story on Major Andre and the traitor Benedict Arnold. 2) I want to be a better man for your sake.

[Tappan, New York, October 2, 1780]

Since my last to you, I have received your letters No. 3 & 4;1 the others are yet on the way. Though it is too late to have the advantage of novelty, to comply with my promise, I send you my account of Arnold’s affair; and to justify myself to your sentiments, I must inform you that I urged a compliance with Andre’s request to be shot and I do not think it would have had an ill effect; but some people are only sensible to motives of policy, and sometimes from a narrow disposition mistake it. …

I fear you will admire the picture so much as to forget the painter. I wished myself possessed of André’s accomplishments for your sake; for I would wish to charm you in every sense. You cannot conceive my avidity for every thing that would endear me more to you. I shall never be satisfied with giving you pleasure, and I am mortified that I do not unite in myself every valuable and agreeable qualification. I do not my love affect modesty. I am conscious of ⟨the⟩ advantages I possess. I know I have talents and a good heart; but why am I not handsome? Why have I not every acquirement that can embellish human nature? Why have I not fortune, that I might hereafter have more leisure than I shall have to cultivate those improvements for which I am not entirely unfit?

Tis not the vanity of excelling others, but the desire of pleasing my Betsey that dictates these wishes. In her eyes I should wish to be the first the most amiable the most accomplished of my sex; but I will make up all I want in love.

Two days since, the bundle directed to your papa was delivered to me. I beg you to present my affectionate compliments with it to your mama.

I am in very good health and shall be in very good spirits when I meet my Betsey.

Adieu

A Hamilton … (Whole letter here)

The wedding

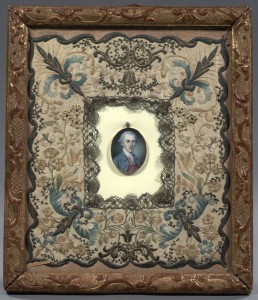

Alexander and Eliza were married on December 14, 1780, at Albany. This miniature by Charles Wilson Peale was perhaps commissioned by Eliza. She probably embroidered the mat, which is rather lovely.

On December 19, 1780, Hamilton wrote to General Washington:

Mrs. Hamilton presents her respectful compliments to Mrs. Washington and yourself. After the holidays we shall be at Head Quarters.

I believe I imparted to you General Schuylers wish that you could make it convenient to pay a visit with Mrs. Washington this winter. He and Mrs. Schuyler have several times repeated their inquiries and wishes. I have told them I was afraid your business would not permit you. If it should, I shall be happy you will enable me to let them know about what period will suit; when the slaying [ahem, Alexander: SLEIGHING] arrives, it will be an affair of two days up and two days down.

With the most respectful attachment I have the honor to be Yr. Excellys. Obed ser

A Hamilton (Whole text here)

Washington replied on December 27, 1780:

Mrs. Washington most cordially joins me, in compliments of congratulations to Mrs. Hamilton & yourself, on the late happy event of your marriage & in wishes to see you both at head Quarters. We beg of you to present our respectful compliments to Generl. Schuyler, his Lady & Family & offer them strong assurances of the pleasure we should feel, at seeing them at New Windsor.

With much truth and great personal regard I am Dr Hamilton Yr affecte. frd & Servt

Go: Washington (Whole letter here)

More

- Last week I finished Hamilton: The Revolution, by Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeremy McCarter. Having worked for a dealer in old and rare books for several decades, I love the fact that the printed version is done in eighteenth-century style: large quarto format, raised bands, spine labels, deckle edges. After seeing the fabulous photos, I almost feel like I’ve seen the show … Mmmm, no, not really. Still trying the lottery. But the book does include excellent photos. Aside from the lyrics with notes by Miranda, it also has a series of enlightening essays on the conception and production of the show. Highly recommended.

- I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the nineteenth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.