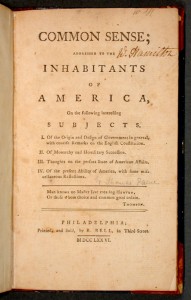

The pamphlet Common Sense, which Angelica mentions in “The Schuyler Sisters,” was published anonymously in Philadelphia, on January 10, 1776. Within a few months, British expatriate Thomas Paine was known to be the author. Although others had made many of the same points [but see the note under More, below], Paine’s confidence in America’s potential and his plain-spoken but forceful writing made copies of Common Sense fly off booksellers’ shelves.

Ranking books according to the percentage of people who read them, Common Sense remains the best-selling book in American history. In 1776, the colonies had a population of about 2.5 million. About 100,000 copies of Common Sense were sold within 3 months. That number soon rose to half a million. The book was frequently read aloud and shared, so its effective circulation was much wider.

Not everyone agreed with Paine (see the second John Adams excerpt below), but Common Sense provided a focal point for discussion. Hamilton’s Vindication of the Measures of Congress,1774 (see also this post), discussed a wide range of topics that concerned the colonists: taxes, trade embargoes, petitions, events in Boston, the merits of the British Parliament vs. the British king. After Common Sense appeared, the debate shifted to one question: whether or not the colonies ought to be independent.

- Of the Origin and Design of Government in general, with concise Remarks on the English Constitution

- Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession

- Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs

- On the Present Ability of America, with some Miscellaneous Reflections

I recently read Common Sense, for the first time ever as far as I can recall. (What were my American History teachers thinking?) The first and second sections were interesting as a reminder that people really did believe monarchs were anointed by God, and that rebellion against a king was a rebellion against God. However, most of my favorite quotes are from the third and fourth sections. I’ll give some of them later in the post. But first, a few contemporary reactions, by people who were as excited as Angelica was about reading Common Sense.

Charles Lee

On January 24, 1776, Major General Charles Lee (“Makes him second in command … He’s not the choice I would have gone with”) wrote to General George Washington:

Have You seen the pamphlet Common Sense? I never saw such a masterly irresistible performance—it will if I mistake not, in concurrence with the transcendant folly and wickedness of the Ministry give the coup de grace to G. Britain—in short I own myself convinc’d by the arguments of the necessity of seperation.

The whole letter, with Lee’s charmingly erratic spelling and punctuation, is here. For Lee and the Battle of Monmouth, see Hamilton Musical posts 22, 23, 24, 26.)

John Adams, February 1776

When Common Sense was published in Philadelphia in January 1776, John Adams (“I know him, that can’t be …”) was in the city as a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. He wrote to his beloved wife Abigail on February 18, 1776:

I sent you from New York a Pamphlet intituled Common Sense, written in Vindication of Doctrines which there is Reason to expect that the further Encroachments of Tyranny and Depredations of Oppression, will soon make the common Faith: unless the cunning Ministry, by proposing Negociations and Terms of Reconciliation, should divert the present Current from its Channell.

Full text of the letter here.

General George Washington, April 1776

Washington not only read Common Sense, but observed its profound impact on his countrymen:

No man does, no man can, wish the restoration of peace more fervently than I do; but I hope, whenever made, it will be upon such terms, as will reflect honor upon the councils and wisdom of America. With you, I think a change in the American representation necessary. Frequent appeals to the people can be attended with no bad, but may have very salutary effects. My countrymen I know, from their form of government, and steady attachment heretofore to royalty, will come reluctantly into the idea of independence, but time and persecution bring many wonderful things to pass; and by private letters, which I have lately received from Virginia, I find “Common Sense” is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men.

Letter to Joseph Reed, April 1, 1776, from The Writings of George Washington.

John Adams, ca. 1801

A quarter century after Common Sense appeared, Adams began jotting down autobiographical notes regarding events in Philadelphia during the spring of 1776. By that time he was less enthusiastic about Common Sense and its author.

I dreaded the Effect so popular a pamphlet might have, among the People, and determined to do all in my Power, to counter Act the Effect of it. My continued Occupations in Congress, allowed me no time to write any thing of any Length: but I found moments to write a small pamphlet which Mr. Richard Henry Lee, to whom I shewed it, liked so well that he insisted on my permitting him to publish it: He accordingly got Mr. Dunlap to print it, under the Tittle of Thoughts on Government in a Letter from a Gentleman to his Friend. Common Sense was published without a Name: and I thought it best to suppress my name too: but as common Sense when it first appeared was generally by the public ascribed to me or Mr. Samuel Adams, I soon regretted that my name did not appear. …

—Paine soon after the Appearance of my Pamphlet hurried away to my Lodgings and spent an Evening with me. His Business was to reprehend me for publishing my Pamphlet. Said he was afraid it would do hurt, and that it was repugnant to the plan he had proposed in his Common Sense. I told him it was true it was repugnant and for that reason, I had written it and consented to the publication of it: for I was as much afraid of his Work [as] he was of mine. His plan was so democratical, without any restraint or even an Attempt at any Equilibrium or Counterpoise, that it must produce confusion and every Evil Work. I told him further, that his Reasoning from the Old Testament was ridiculous, and I could hardly think him sincere. At this he laughed, and said he had taken his Ideas in that part from Milton: and then expressed a Contempt of the Old Testament and indeed of the Bible at large, which surprized me. He saw that I did not relish this, and soon check’d himself, with these Words “However I have some thoughts of publishing my Thoughts on Religion, but I believe it will be best to postpone it, to the latter part of Life.” …

The third part of Common Sense which relates wholly to the Question of Independence, was clearly written and contained a tollerable Summary of the Arguments which I had been repeating again and again in Congress for nine months. But I am bold to say there is not a Fact nor a Reason stated in it, which had not been frequently urged in Congress. The Temper and Wishes of the People, supplied every thing at that time: and the Phrases, suitable for an Emigrant from New Gate, or one who had chiefly associated with such Company, such as “The Royal Brute of England,” “The Blood upon his Soul,” and a few others of equal delicacy, had as much Weight with the People as his Arguments. It has been a general Opinion, that this Pamphlet was of great Importance in the Revolution. I doubted it at the time and have doubted it to this day. It probably converted some to the Doctrine of Independence, and gave others an Excuse for declaring in favour of it.

Full text of this section of Adams’ autobiographical notes here. In Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (a very readable introduction to the Founding Fathers and the Revolution), A.J. Langguth bases much of his description of Paine in Philadelphia on Adams’s notes.

My Favorite Quotes from Common Sense

The whole text of Common Sense is available on Project Gutenberg.

Time vs. reason

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not YET sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing WRONG, gives it a superficial appearance of being RIGHT, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.

Sad, but true for most people.

Society vs. government

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness POSITIVELY by uniting our affections, the latter NEGATIVELY by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first a patron, the last a punisher.

Interesting distinction, isn’t it?

“The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ’Tis time to part”

Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain. The next war may not turn out like the last, and should it not, the advocates for reconciliation now will be wishing for separation then, because, neutrality in that case, would be a safer convoy than a man of war. Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ’Tis time to part. Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven.

A very persuasive argument, given events in Boston in 1775.

“It is not in the power of Britain or of Europe to conquer America, if she do not conquer herself by delay and timidity”

I just can’t seem to edit this excerpt down … And I don’t really want to. It gives you a feel for the flow of Paine’s argument, the emotion he packed into it, and the impact of having ideas expressed in powerful prose suitable for reading aloud.

It is the good fortune of many to live distant from the scene of sorrow; the evil is not sufficient brought to their doors to make them feel the precariousness with which all American property is possessed. But let our imaginations transport us for a few moments to Boston, that seat of wretchedness will teach us wisdom, and instruct us for ever to renounce a power in whom we can have no trust. The inhabitants of that unfortunate city, who but a few months ago were in ease and affluence, have now, no other alternative than to stay and starve, or turn out to beg. Endangered by the fire of their friends if they continue within the city, and plundered by the soldiery if they leave it. In their present condition they are prisoners without the hope of redemption, and in a general attack for their relief, they would be exposed to the fury of both armies.

Men of passive tempers look somewhat lightly over the offences of Britain, and, still hoping for the best, are apt to call out, “Come, come, we shall be friends again, for all this.” But examine the passions and feelings of mankind, Bring the doctrine of reconciliation to the touchstone of nature, and then tell me, whether you can hereafter love, honour, and faithfully serve the power that hath carried fire and sword into your land? If you cannot do all these, then are you only deceiving yourselves, and by your delay bringing ruin upon posterity. Your future connection with Britain, whom you can neither love nor honour, will be forced and unnatural, and being formed only on the plan of present convenience, will in a little time fall into a relapse more wretched than the first. But if you say, you can still pass the violations over, then I ask, Hath your house been burnt? Hath your property been destroyed before your face? Are your wife and children destitute of a bed to lie on, or bread to live on? Have you lost a parent or a child by their hands, and yourself the ruined and wretched survivor? If you have not, then are you not a judge of those who have. But if you have, and still can shake hands with the murderers, then are you unworthy of the name of husband, father, friend, or lover, and whatever may be your rank or title in life, you have the heart of a coward, and the spirit of a sycophant.

This is not inflaming or exaggerating matters, but trying them by those feelings and affections which nature justifies, and without which, we should be incapable of discharging the social duties of life, or enjoying the felicities of it. I mean not to exhibit horror for the purpose of provoking revenge, but to awaken us from fatal and unmanly slumbers, that we may pursue determinately some fixed object. It is not in the power of Britain or of Europe to conquer America, if she do not conquer herself by delay and timidity. The present winter is worth an age if rightly employed, but if lost or neglected, the whole continent will partake of the misfortune; and there is no punishment which that man will not deserve, be he who, or what, or where he will, that may be the means of sacrificing a season so precious and useful.

It is repugnant to reason, to the universal order of things to all examples from former ages, to suppose, that this continent can longer remain subject to any external power. The most sanguine in Britain does not think so. The utmost stretch of human wisdom cannot, at this time, compass a plan short of separation, which can promise the continent even a year’s security. Reconciliation is now a fallacious dream. Nature hath deserted the connexion, and Art cannot supply her place. For, as Milton wisely expresses, “never can true reconcilement grow where wounds of deadly hate have pierced so deep.”

Every quiet method for peace hath been ineffectual. Our prayers have been rejected with disdain; and only tended to convince us, that nothing flatters vanity, or confirms obstinacy in Kings more than repeated petitioning—and nothing hath contributed more than that very measure to make the Kings of Europe absolute: Witness Denmark and Sweden. Wherefore, since nothing but blows will do, for God’s sake, let us come to a final separation, and not leave the next generation to be cutting throats, under the violated unmeaning names of parent and child.

To say, they will never attempt it again is idle and visionary, we thought so at the repeal of the stamp-act, yet a year or two undeceived us; as well may we suppose that nations, which have been once defeated, will never renew the quarrel.

As to government matters, it is not in the power of Britain to do this continent justice: The business of it will soon be too weighty, and intricate, to be managed with any tolerable degree of convenience, by a power, so distant from us, and so very ignorant of us; for if they cannot conquer us, they cannot govern us. To be always running three or four thousand miles with a tale or a petition, waiting four or five months for an answer, which when obtained requires five or six more to explain it in, will in a few years be looked upon as folly and childishness—There was a time when it was proper, and there is a proper time for it to cease.

Small islands not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island. In no instance hath nature made the satellite larger than its primary planet, and as England and America, with respect to each other, reverses the common order of nature, it is evident they belong to different systems: England to Europe, America to itself.

I am not induced by motives of pride, party, or resentment to espouse the doctrine of separation and independance; I am clearly, positively, and conscientiously persuaded that it is the true interest of this continent to be so; that every thing short of that is mere patchwork, that it can afford no lasting felicity,—that it is leaving the sword to our children, and shrinking back at a time, when, a little more, a little farther, would have rendered this continent the glory of the earth.

As Britain hath not manifested the least inclination towards a compromise, we may be assured that no terms can be obtained worthy the acceptance of the continent, or any ways equal to the expence of blood and treasure we have been already put to.The object, contended for, ought always to bear some just proportion to the expence. The removal of North, or the whole detestable junto, is a matter unworthy the millions we have expended. A temporary stoppage of trade, was an inconvenience, which would have sufficiently ballanced the repeal of all the acts complained of, had such repeals been obtained; but if the whole continent must take up arms, if every man must be a soldier, it is scarcely worth our while to fight against a contemptible ministry only. Dearly, dearly, do we pay for the repeal of the acts, if that is all we fight for; for in a just estimation, it is as great a folly to pay a Bunker-hill price for law, as for land. As I have always considered the independancy of this continent, as an event, which sooner or later must arrive, so from the late rapid progress of the continent to maturity, the event could not be far off. Wherefore, on the breaking out of hostilities, it was not worth the while to have disputed a matter, which time would have finally redressed, unless we meant to be in earnest; otherwise, it is like wasting an estate on a suit at law, to regulate the trespasses of a tenant, whose lease is just expiring. No man was a warmer wisher for reconciliation than myself, before the fatal nineteenth of April 1775, but the moment the event of that day was made known, I rejected the hardened, sullen tempered Pharaoh of England for ever; and disdain the wretch, that with the pretended title of father of his people can unfeelingly hear of their slaughter, and composedly sleep with their blood upon his soul.

The need for a declaration of independence

And finally, here’s Paine’s summary. Read it, and then read the Declaration of Independence.

To Conclude, however strange it may appear to some, or however unwilling they may be to think so, matters not, but many strong and striking reasons may be given, to shew, that nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independance. Some of which are,

First.—It is the custom of nations, when any two are at war, for some other powers, not engaged in the quarrel, to step in as mediators, and bring about the preliminaries of a peace: but while America calls herself the Subject of Great-Britain, no power, however well disposed she may be, can offer her mediation. Wherefore, in our present state we may quarrel on for ever.

Secondly.—It is unreasonable to suppose, that France or Spain will give us any kind of assistance, if we mean only, to make use of that assistance for the purpose of repairing the breach, and strengthening the connection between Britain and America; because, those powers would be sufferers by the consequences.

Thirdly.—While we profess ourselves the subjects of Britain, we must, in the eye of foreign nations, be considered as rebels. The precedent is somewhat dangerous to their peace, for men to be in arms under the name of subjects; we, on the spot, can solve the paradox: but to unite resistance and subjection, requires an idea much too refined for common understanding.

Fourthly.—Were a manifesto to be published, and despatched to foreign courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceable methods we have ineffectually used for redress; declaring, at the same time, that not being able, any longer, to live happily or safely under the cruel disposition of the British court, we had been driven to the necessity of breaking off all connections with her; at the same time, assuring all such courts of our peaceable disposition towards them, and of our desire of entering into trade with them: Such a memorial would produce more good effects to this Continent, than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain.

Under our present denomination of British subjects, we can neither be received nor heard abroad: The custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until, by an independance, we take rank with other nations.

These proceedings may at first appear strange and difficult; but, like all other steps which we have already passed over, will in a little time become familiar and agreeable; and, until an independance is declared, the Continent will feel itself like a man who continues putting off some unpleasant business from day to day, yet knows it must be done, hates to set about it, wishes it over, and is continually haunted with the thoughts of its necessity.

More

- As a historian, I’m always on the look-out for facts and context I’ve missed. It’s what all good historians do: expand their knowledge and integrate it with what they already know. I realized early on in this series of blog posts that due to time constraints (the job that pays the mortgage), I wouldn’t be able to read widely in secondary sources. That meant my grasp of the historical context might not always be correct. So I was thrilled when Gary Berton of the Thomas Paine National Historical Association emailed me a correction to my first paragraph in this essay:

Common Sense did not just reiterate the points made before him in stronger language. He introduced to the world what would become the foundations of democracy, which Adams and Hamilton denounced: one-person, one-vote; no rule by elites; monarchy is not only absurd but illegal; we can’t base our government on tradition or religion (he denounced the concept of original sin); representative democracy; a constitution designed to protect rights; and more. These formed the basis for the age of democratic revolutions which morphed into the progressive struggles under industrial capitalism. (Quoted with Mr. Berton’s permission)

- Thomas Paine used to live at what is now 309 Bleecker St. – currently the home of the Reiss store, between Grove and 7th Avenue. Read the details in the excellent blog post by Dayton in Manhattan.

- A relief plaque with a portrait of Paine commemorates his residence at a nearby house on Grove Street: see the blog post by Forgotten New York.

- I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the eleventh in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Keep in touch! Members of my email list get a weekly message with four recommendations in fields such as sculpture, painting, literature, nonfiction, movies, architecture, and decorative arts. To be added, send your email to DuranteDianne@gmail.com. You can also sign up for the RSS feed of this blog, follow me on Twitter @NYCsculpture, or friend the Forgotten Delights page on Facebook.