- Scuptor: Henry Kirke Brown

- Date: 1868

- Location: North end of Union Square, near 16th St.

Abraham Lincoln on the Constitution

In February 1861, shortly before his first inauguration as president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln met with a delegation of New Yorkers who were concerned with the effect that war with the South might have on the commerce of New York. William E. Dodge, a prominent New York merchant (his sculpture still stands in Bryant Park), asked the question on everyone’s mind. Here’s the exchange, as recorded by Lucius E. Chittenden of Vermont (online here).

As soon as his opportunity [Dodge] raised his voice enough to be heard by all present, and, addressing Mr. Lincoln, declared that the whole country in great anxiety was awaiting his inaugural address, and then added: “It is for you, sir, to say whether the whole nation shall be plunged into bankruptcy; whether the grass shall grow in the streets of our commercial cities.”

“Then I say it shall not,” [Lincoln] answered, with a merry twinkle of his eye. “If it depends upon me, the grass will not grow anywhere except in the fields and the meadows.”

“Then you will yield to the just demands of the South. You will leave her to control her own institutions. You will admit slave states into the Union on the same conditions as free states. You will not go to war on account of slavery!”

A sad but stern expression over Mr. Lincoln’s face. “I do not know that I understand your meaning, Mr. Dodge,” he said, without raising his voice, “Nor do I know what my acts or my opinions may be in the future, beyond this. If I shall ever come to the great office of President of the United States, I shall take an oath. I shall swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, of all the United States, and that I will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. This is a great and solemn duty. With the support of the people and the assistance of the Almighty I shall undertake to perform it. I have full faith that I shall perform it. It is not the Constitution as I would like to have it, but as it is, that is to be defended. The Constitution will not be preserved and defended until it is enforced and obeyed in every part of every one of the United States. It must be so respected, obeyed, enforced, and defended, let the grass grow where it may.”

Not a word or a whisper broke the silence…Mr. Dodge attempted no reply.

March 1863: Lincoln, Vallandigham, and habeas corpus

In March 1863, the third year of the Civil War was about to begin. With Union volunteers reduced to a trickle, Lincoln had signed the Conscription Act authorizing the draft. Clement Vallandigham, a prominent “Copperhead” politician (a.k.a. a “Peace Democrat” or Southern sympathizer) closed a rousing speech in New York City with an exhortation to fellow Democrats: “He denied that we owe any obedience to our conscription act … We are under no obligation to respond beyond the limits of law constitutionally enacted” (reported in the New York Times). Two months later in Ohio, Vallandigham told another crowd that the war was “wicked, cruel and unnecessary – a war not being waged for the preservation of the Union, but for the purpose of crushing out liberty and establishing a despotism – a war for the freedom of the blacks and the enslaving of the whites.”

The governor of the Military Department of the Ohio (which included the state of Kentucky, a front-line zone) promptly arrested Vallandigham and had him court-martialed. He was sentenced to close confinement in (horrors!) Boston. Vallandigham’s lawyer requested a writ of habeas corpus, which would have brought Vallandigham before a civilian court. The petition was denied.

Lincoln, who had a sense of humor as well as a canny political mind, transmuted Vallandigham’s sentence, ordering that he spend the duration of the war in the Confederacy. Writing in June 1863 to the irate Albany Democratic Committee, Lincoln explained:

[H]e who dissuades one man from volunteering, or induces one soldier to desert, weakens the Union cause as much as he who kills a Union soldier in battle. Yet this dissuasion or inducement may be so conducted as to be no defined crime of which any civil court would take cognizance.

Ours is a case of rebellion – so called by the resolutions before me – in fact, a clear, flagrant, and gigantic case of rebellion: and the provision of the Constitution that ‘the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it,’ is the provision which specially applies to our present case. …

[Mr. Vallandigham] was not arrested because he was damaging the political prospects of the Administration, or the personal interests of the Commanding-General, but because he was damaging the army, upon the existence and vigor of which the life of the nation depends. He was warring upon the military, and this gave the military constitutional jurisdiction to lay hands upon him. …

I can no more be persuaded that the Government can constitutionally take no strong measures in time of rebellion, because it can be shown that the same could not be lawfully taken in time of peace, than I can be persuaded that a particular drug is not good medicine for a sick man, because it can be shown not to be good food for a well one. — Lincoln to the Albany Democratic Convention, 1863

Vallandigham promptly fled the South for Niagara Falls, and by mid-1864 had resumed his political life, without any interference from the Lincoln administration.

Vallandigham’s arrest was a cause celebre at the time, although it turned out to be of negligible consequence to the outcome of the war. But it does raise some fascinating questions that are still worthy of debate. Are there limits to free speech when a country is at war, rather than at peace? Do civilians ever fall under military jurisdiction? Can a government established to protect individual rights temporarily abrogate those rights, if the very existence of the government is at stake – if some citizens are attempting to overthrow the government by force, rather than by the means established in the Constitution?

Lincoln’s assassination

Lincoln was assassinated on 4/15/1865, just 6 days after Lee had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse. In “O Captain! My Captain!” Walt Whitman contrasts the joy of having the Civil War finally brought to an end with the death of the president. (To read it in its proper formatting, click here.)

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills,

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding,

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning;

Here Captain! dear father!

This arm beneath your head!

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done,

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

Other Lincolns

Saint Gaudens’s Standing Lincoln in Chicago, dedicated in 1887, is one of our best images of Lincoln and one of the greatest works of American sculpture. Here it is with the full setting.

The only serious competition for the title of best Lincoln sculpture is Daniel Chester French’s figure in the Lincoln Memorial, in Washington, D.C.

For more on evaluating sculptures in esthetic, philosophical, emotional, or art-historical terms, see the Appendix A (“How to Read a Sculpture”) in Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan and Getting More Enjoyment from Art You Love.

Favorite Lincoln Speeches

Lincoln on individual rights vs. divine right:

That is the real issue. … It is the eternal struggle between these two principles – right and wrong – throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time, and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity, and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You toil and work and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king, who seeks to bestride the people ofhis own nation and live by the fruit of their labour, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, – it is the same tyrannical principle. … Whenever the issue can be distinctly made, and all extraneous matter thrown out, so that men can fairly see the real difference between the parties, this controversy will soon be settled, and it will be done peaceably, too. There will be no war, no violence. It will be placed again where the wisest and best men of the world placed it. – Lincoln, from the final Douglas Debate, 10/15/1858

And one of the great short speeches of all time:

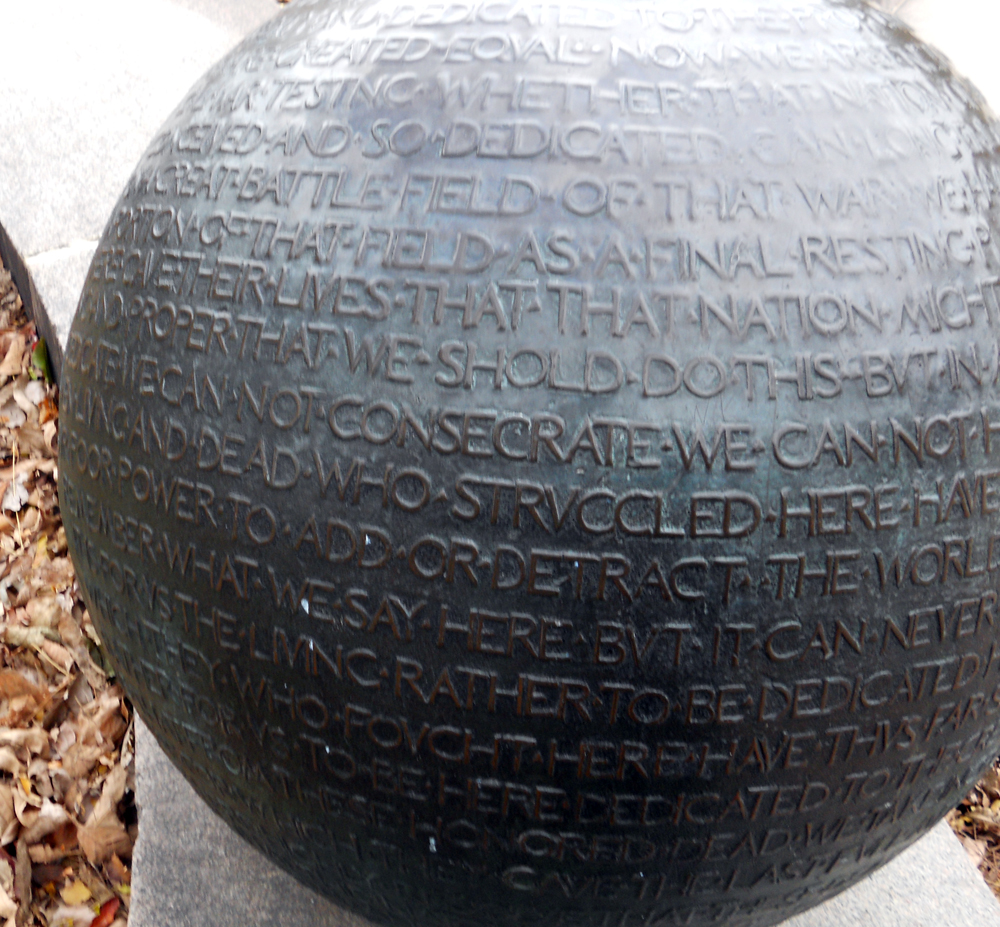

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here; but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln, Gettysburg Addess, read at the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg on 11/19/1863

Gettysburg Address, on one of the spheres flanking Saint Gaudens’s Lincoln in Chicago. Photo copyright © 2019 Dianne L. Durante

More

- Henry Kirke Brown also did the equestrian George Washington at the south side of Union Square.

- For more on this sculpture, see Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan.

- In Getting More Enjoyment from Sculpture You Love, I demonstrate a method for looking at sculptures in detail, in depth, and on your own. Learn to enjoy your favorite sculptures more, and find new favorites. Available on Amazon in print and Kindle formats. More here.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.