Here are the main characters on the American Revolutionary scene, in September and October 1781 – skewed, of course, to those who appear in Hamilton: An American Musical.

The Americans

- George Washington: commander-in-chief of the Continental Army since June 1775. He has not fought the British on the battlefield since the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. In terms of number of soldiers, finances, and supplies, his army is in bad shape, as he has repeatedly told members of Congress. (See this post: search for “despondent”.)

- John Laurens: formerly on Washington’s staff, where he and Hamilton became friends. A few months ago, he returned from a mission to France, where he helped persuade Louis XVI to send more money, ammunition, and arms to the Americans. (See this post.)

- Alexander Hamilton: on 7/31/1781, he was finally given a battalion to command in the field. As of late August, he is on the move with the Continental Army and its French allies from New York to Virginia. See the end of last week’s post.

The French

- Marquis de Lafayette, “America’s favorite fighting Frenchman”: one of the few figures in the Revolution who has nationwide rather than local appeal. He has been fighting beside the Americans since 1777, when he was 19 years old. In 1779-1780, he returned to France to persuade King Louis XVI to send soldiers, supplies, and money to the Americans. (See last week’s post.)

- Comte de Rochambeau: in charge of a French fleet based at Newport, Rhode Island, since early 1780. (Again, see last week’s post.)

- Admiral De Grasse: in charge of the 1781 West Indies fleet, which sailed to the Caribbean to fight the British there, and to collect money from the French colonies. De Grasse’s fleet has been given orders to coordinate operations with the Franco-American forces … but only until mid-October. Then the fleet must sail back to France before winter sets in.

The British

- Sir Henry Clinton: commander-in-chief of the British forces in America, a ditherer who does his best not to take any action on his own responsibility. His headquarters are New York City, which has been in British hands since August 1776. (See this post.)

- Lord Charles Cornwallis: a brilliant soldier, chafing as second-in-command of the British forces under Clinton.

The British rampage through the South

In the northern United States, the British made no significant gains against Washington after 1776. In 1778, they decided to shift the theater of war to the southern states, where there were fewer people – and a greater percentage of the population was loyalist. First up: Savannah, Georgia, which Clinton and Cornwallis captured in December 1778. (Theodosia’s husband was named governor of Georgia.)

In May 1780, Clinton and Cornwallis captured Charleston, South Carolina. Then Clinton returned to New York, and Cornwallis battled his way northward through the Carolinas. By early 1781, he had reached Virginia. There he took command of additional troops (some of which had been serving under the traitor Benedict Arnold), bringing his force up to some 7,000 men.

The Marquis de Lafayette, with a force too small to meet the British on the field, desperately attempted to prevent the British from having it all their own way as they ravaged the populous and wealthy state of Virginia. “When he changes his position,” explained Lafayette, “I try to give to his movements the appearance of defeat” (quoted here). Lafayette’s aide, James McHenry, wrote on 7/11/1781: “Legerdemain is a very necessary science for an American general at this moment.”

In early summer 1781, Clinton, fearing an attack on New York, ordered Cornwallis to send several thousand of his men to New York. Then he declared instead that Cornwallis should settle down for the winter somewhere on the Chesapeake Bay, and fortify a deep-water base for future British naval operations. Maintaining control of the Bay would give the British easy access to hundreds of square miles of vulnerable American territory.

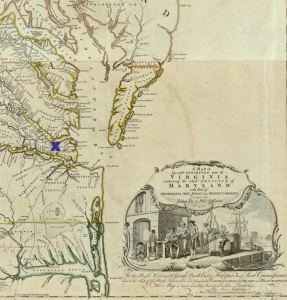

Obeying orders and suppressing his trained military instincts, Cornwallis chose as his base Yorktown, a once thriving tobacco-shipping port on the York River that served as the harbor for Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia. (See the blue “x” on the map above.) Its 300 houses had been largely deserted since the inhabitants fled inland to escape British raids.

Uh-oh. In late August, soon after Cornwallis settled in at Yorktown, Admiral De Grasse’s fleet of 29 ships arrived from the West Indies and blockaded the entrance to the York River.

When the British fleet under Admiral Graves arrived from New York, the French fleet prevented them from reaching Cornwallis at Yorktown. Not only that: at the Battle of Chesapeake (9/5/1781), the French inflicted so much damage that the British fleet limped back to New York for repairs and reinforcements.

Cornwallis and his soldiers were left with only a few ships – too few to transport them out of Yorktown. But in a letter Cornwallis received on September 29, Clinton promised to send a fleet to his rescue within a few days.

Yorktown’s situation

Yorktown had been built as port and a commercial center. It sat on swamp land near a harbor, and lacked any military advantages such as a high elevation. Cornwallis, blockaded in, ordered the construction of earthwork fortifications around the town, and another line further out. Then he resigned himself to waiting for rescue. On September 16, he wrote to Clinton:

If I had no hopes of relief I would rather risk an action than defend my half finished works but as you say Digby is hourly expected and promise every exertion to assist me I do not think myself justified in putting the fate of the war on so desperate an attempt. By examining the transports with care and turning out useless mouths my provisions will last at least six weeks from this day if we can preserve them from accidents. This place is in no state of defence. If you cannot relieve me very soon you must be prepared to hear the worst … (Quoted here)

For an escape hatch, Cornwallis fortified and posted troops at Gloucester Point, less than a mile away on the north side of the York River. If the British fleet didn’t arrive to save him, he could ferry his troops across and march north from Gloucester.

On October 2, Cornwallis received another letter from Clinton: the fleet would not be setting out until October 5 at the earliest. It would take at least a week after that to arrive.

The Americans and French besiege Yorktown

Meanwhile, the 15,000 or so Franco-American forces, who had been on the move since mid-August, were struggling with dire shortage of transport and food. But on September 28, 1781, they finally settled down about a mile outside Yorktown and began softening up the British with an artillery bombardment. Cornwallis, realizing that his outer defenses were too weak to withstand such bombardment for long, soon pulled nearly all his men and artillery back to the innermost defenses: the earthenworks just outside Yorktown.

On October 6, the allies began digging a trench (a.k.a. “paralllel”) 2,000 yards long, and 600 yards away from the British defenses. The trench was so deep that the allied troops could move through it with little danger of being hit by British fire. The dirt from the trench was used to build a parapet facing the enemy, on which artillery could be positioned. (For an eyewitness account, see The Journal of Colonel Daniel Trabue). By October 9th, the first trench was complete, and the new series of batteries and redoubts was bombarding the British position even more fiercely.

On October 11, the allies began construction of a second trench, this one only 300 yards from the British earthenworks.

Alexander wrote to Eliza (about 6 months pregnant) on October 12, 1781:

Thank heaven, our affairs seem to be approaching fast to a happy period. Last night our second parallel commenced. Five days more the enemy must capitulate or abandon their present position; if they do the latter it will detain us ten days longer; and then I fly to you. Prepare to receive me in your bosom. Prepare to receive me decked in all your beauty, fondness and goodness. With reluctance I bid you adieu.

Adieu My darling Wife My beloved Angel Adieu

A Hamilton (More here)

The second trench ran directly toward two redoubts that the British were still manning in what had been their outermost lines. Redoubt 10 was on the banks of the York River. Redoubt 9 was about a quarter mile to the west. The second trench could not be completed as long as the enemy held these two redoubts, whose position allowed them to unleash a barrage of fire at the men digging the trench. Both redoubts had to be neutralized at once, since either redoubt could fire mercilessly on the other.

So: The next step was to capture those redoubts. The order went out that the redoubts would be stormed on October 14, soon after sundown. The French were to attack Redoubt 9. The Americans, with Alexander Hamilton leading, were to attack Redoubt 10.

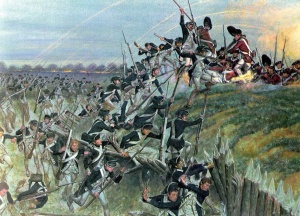

The British redoubts at Yorktown

Let’s pause here, waiting for the signal to storm the redoubts, and ask: what is it Hamilton and the other attackers are facing?

First of all: the redoubt. A redoubt is an arrangement of dirt, trees, and whatever other large obstacles the defenders can contrive that will make an approach to their position more difficult for the attackers. (The U.S. Army Heritage site has a great pic of a reconstructed redoubt at Yorktown.)

At Yorktown, Redoubt 10’s outermost defense is a 15-foot-high dirt wall protected with abatis (same singular or plural). To make abatis, the defenders cut down trees, trim their branches at nastily sharp angles, then shove the trunks firmly in the outer dirt wall, spiky bits facing outward. The longer the the attackers have to struggle to get past the abatis, the longer the defenders can shoot at them.

Once past the abatis, the attackers must cross the glacis, an area of rising ground designed to expose them to yet more fire from the defenders. After that comes a ditch: sharpened logs in the middle make crossing it more difficult. The side of the ditch closest to the redoubt is the steep slope (a scarp) topped with rows of sharpened logs pointing outward (the fraises). Beyond the scarp and fraises is the parapet, from which the defenders are shooting at the attackers. Redoubts 9 and 10 had a total of 65 pieces of artillery.

Once at the parapet, the attackers are in hand-to-hand combat with the defenders. At Redoubts 9 and 10, that was some 180 well-trained, battle-hardened British soldiers.

And what’s coming at the attackers while they push their way through these obstacles? Considerably more than the business end of a bayonet.

Revolutionary War weaponry

The largest cannons at Yorktown shot 18- and 24-pound balls. (Nice pic of Revolutionary War cannon at Yorktown here.) You do not want to get in the way of a cannon ball. A German soldier in service of the French reported:

Another fatality. While working on a fortification during this siege, Soldier [Mathias] Eisenbarth from Saar Wellingen was cut in half right down the middle by an enemy cannon ball. (More here)

The good news is that at Redoubt 10, the attackers probably won’t have British cannons shooting at them. Cannons send their projectiles in a long, low arc – great for long-range devastation, but not useful at close quarters.

What the attackers face instead, as they close in, are mortars and howitzers. These look like short-barreled cannon. (Nice pic of Revolutionary War howitzer at Yorktown here, mortar here.) Mortars and howitzers shoot their projectiles more steeply upwards than cannons. The projectiles fall – at murderous speed – quite nearby.

Aside from a standard cannonball, a mortar or howitzer could be loaded with an explosive shell: a 3-inch thick hollow ball packed with explosive that trailed a fuse. Shells were unpredictable in the 18th century: they might explode in the air, on impact, or soon after hitting the ground. (I’m pretty sure this 1814 image of the attack that inspired the “Star-Spangled Banner” shows such explosive shells – “the bombs bursting in air.”) Daniel Trabue described them:

The shells were made of pot metal like a jug 1-2 inch thick, without a handle, & with a big mouth. They were filled with powder, and other combustibles in such a manner that the blaze came out of the mouth, and keeps on burning until it gets to the body where the powder is, then it bursts and the pieces fly every way, and wound & kill whoever it hits. (More here, p. 112)

James Thacher, an American surgeon, described the shells on the evening of the 15th:

The bomb-shells from the besiegers and the besieged are incessantly crossing each others’ path in the air. They are clearly visible in the form of a black ball in the day, but in the night, they appear like a fiery meteor with a blazing tail, most beautifully brilliant, ascending majestically from the mortar to a certain altitude, and gradually descending to the spot where they are destined to execute their work of destruction. It is astonishing with what accuracy an experienced gunner will make his calculations, that a shell shall fall within a few feet of a given point, and burst at the precise time, though at a great distance. When a shell falls, it whirls round, burrows, and excavates the earth to a considerable extent, and bursting, makes dreadful havoc around. I have more than once witnessed fragments of the mangled bodies and limbs of the British soldiers thrown into the air by the bursting of our shells … (More here)

Explosive shells were enormously destructive. Joseph Plumb Martin, describing the attack on Redoubt 10, wrote:

We were now at a place where many of our large shells had burst the ground, making holes sufficient to bury an ox in. The men, having their eyes fixed upon what was transacting before them, were every now and then falling into these holes. I thought the British were killing us off at a great rate. At length, one of the holes happening to pick me up, I found out the mystery of the huge slaughter. (More here)

A mortar or howitzer could also be loaded with grapeshot: a couple dozen musket balls in a canvas bag. After firing, the bag exploded and the shot scattered, like a modern shotgun blast. (Picture here: search for “grape shot”).

By mid-October, the French and Americans had about a hundred pieces of artillery (including cannons, mortars, howitzers) firing on the British at Yorktown. As long as the ammo held out, the British were firing at least that many pieces back at the allies. A German soldier fighting for the British described the scene at Yorktown on October 11, three days before the storming of Redoubts 9 and 10:

During these 24 hours, 3,600 shot were counted from the enemy, which they fired at the town, our line and at the ships in the harbour. These ships were miserably ruined and shot to pieces. Also the bombs and cannon balls hit many inhabitants and Negroes of the city, and marines, soldiers, and sailors. One saw men lying nearly everywhere who were mortally wounded and whose heads, arms and legs had been shot off. (Quoted here)

Artillery is relatively long-distance weapon. If the attackers get closer, the defenders can throw hand grenades. Like explosive shells, they’re unpredictable, but if that hand-sized bomb goes off at the right moment, it can take down a couple attackers.

A musket is more reliable for close-up defense, but a musket only holds one bullet, and takes about 20 seconds to reload – by which point the enemy might be on top of you. If he is, there’s the business end of your bayonet, a 17-inch piece of triple-edged steel attached to the end of your 5-foot-long musket. (Triple-edged because a triangular wound is more difficult to stitch together.)

Add to all these devastating weapons the fact that medicine at this time is primitive. There’s no knowledge of germs, asepsis, antibiotics. A severe wound to the head or torso usually resulted in death. A severe wound to a limb was treated with amputation and cauterization, so an infection wouldn’t kill the victim.

You might argue that all these weapons were typical of 18th-century warfare, and that the soldiers at Yorktown were accustomed to such hazards. I don’t think one gets accustomed to facing horrendous death just because it’s common.

Are you ready to storm Redoubt 10 yet?

Raise a glass to freedom, and to all the soldiers who have, are, and will fight for it.

And now, it’s 7:30 p.m. on the night of October 14, 1781, and the signal has just gone up to storm Redoubts 9 and 10.

The attack on Redoubt 9

Four hundred French soldiers were assigned to capture Redoubt 9. They lost the element of surprise when a German sentry heard them approaching, but waited for their pioneers to clear away the abatis before rushing forward. Within half an hour the French had captured the redoubt and taken 120 British and Hessians prisoner. Numbers of French casualties vary in the primary sources, but the total wounded and killed seems to have been just over a hundred.

Guillaume, vicomte de Deux-Ponts, who led the French, noted in his journal:

Before starting, I had ordered that no one should fire before reaching the crest of the parapet of the redoubt; and when established upon the parapet, that no one should jump into the works before receiving the orders to do so. …

Our fire was increasing, and making terrible havoc among the enemy, who had placed themselves behind a kind of intrenchment of barrels, where they were well massed, and where all our shots told. We succeeded at the moment when I wished to give the order to leap into the redoubt and charge upon the enemy with the bayonet; then they laid down their arms, and we leaped in with more tranquillity and less risk. I shouted immediately the cry of Vive le Roi, which was repeated by all the grenadiers and chasseurs who were in good condition, by all the troops in the trenches, and to which the enemy replied by a general discharge of artillery and musketry. I never saw a sight more beautiful or more majestic. I did not stop to look at it; I had to give attention to the wounded, and directions to be observed towards the prisoners. (More here)

The attack on Redoubt 10

On the American side, the Marquis de Lafayette was in overall command, and he had put the 400 troops attacking Redoubt 10 under the command of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton assigned Lt.-Colonel John Laurens to hustle around to the other side of the redoubt and prevent the British from escaping in that direction.

In Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts of General Lafayette, compiled by Lafayette much later in his life and published after his death, he makes the following brief comment on the taking of Redoubt 10. (As often at this period, it’s written in third person.)

It became necessary to attack two redoubts. One of these attacks was confided to the Baron de Viomenil, the other to General Lafayette. The former had expressed, in a somewhat boasting manner, the idea he had of the superiority of the French in an attack of that kind; Lafayette, a little offended, answered, “We are but young soldiers, and we have but one sort of tactic on such occasions, which is, to discharge our muskets, and push on straight with our bayonets.” He led on the American troops, of whom he gave the command to Colonel Hamilton, with the Colonels Laurens and Gimat under him. The American troops took the redoubt with the bayonet. As the firing was still continued on the French side, Lafayette sent an aide-de-camp to the Baron de Viomenil, to ask whether he did not require some succour from the Americans; but the French were not long in taking possession also of the other redoubt … (More here )

Why did the Americans plan a bayonet charge? None of the primary sources written by officers explain: probably too obvious to them. It may have been done to keep an accidental discharge from warning the British. Or perhaps it made for a faster charge – keep the soldiers running forward, rather than having them take time to aim and reload. According to Fleming, the British took pride in winning battles using bayonets; so perhaps the Americans did as well.

Captain James Duncan kept a journal of events at Yorktown that includes the storming of Redoubt 10.

Oct 15: I have just said we were ordered yesterday to the trenches. The French grenadiers were ordered out the same time and all for the purpose of storming two redoubts on the enemy’s left. Our division arrived at the deposite of the [NOTE: manuscript is defective here] a little before dark where every man was ordered to disencumber himself of his pack. The evening was pretty dark and favored the attack. The column advanced, Col. Guinot’s [i.e., Gimat’s] regiment in front and ours in the rear. We had not got far before we were discovered, and now the enemy opened a fire of cannon, grape shot, shell, and musketry upon us but all to no effect. The column moved on undisturbed and took the redoubt by the bayonet without firing a single gun. The enemy made an obstinate defense but what cannot brave men do when determined. We had 7 men killed and 30 wounded. Among the latter were Col Guinot [i.e., Gimat], Maj. Barber, and Capt Olney. Fifteen men of the enemy were killed and wounded in the work; 20 were taken prisoners besides Maj. Campbell who commanded, a captain, and one ensign. The chief of the garrison made their escape during the storm by a covered way. (More here; I’ve added a lot of punctuation)

Captain Stephen Olney’s account includes such details as how he made his way through the abatis:

The column marched in silence, with guns unloaded, and in good order. … When we came near the front of the abatis the enemy fired a full body of musketry. At this our men broke silence and huzzaed and as the order for silence seemed broken by every one, I huzzaed with all my power saying “see how frightened they are they fire right into the air.” The pioneers began to cut off the abatis which were the trunks of trees with the trunk part fixed in the ground the limbs made sharp and pointed towards us. This seemed tedious work in the dark within three rods [NOTE: about 15 yards]of the enemy and I ran to the right to look a place to crawl through, but returned in a hurry without success fearing the men would get through first; as it happened I made out to get through about the first and entered the ditch and when I found my men to the number of ten or twelve had arrived, I stepped through between two palisades, one having been shot off to make room on to the parapet, and called out in a tone as if there was no danger, “Captain Olney’s company form here.”

On this I had not less than six or eight bayonets pushed at me. I parried as well as I could with my espontoon [NOTE: a pike with pointy bits at the end], but they broke off the blade part and their bayonets slid along the handle of my espontoon and scaled my fingers, one bayonet pierced my thigh, another stabbed me in the abdomen just above the hip bone. One fellow fired at me and I thought the ball took effect in my arm; by the light of his gun I made a thrust with the remains of my espontoon in order to injure the sight of his eyes but as it happened I only made a hard stroke in his forehead. At this instant two of my men, John Strange and Benjamin Bennett, who had loaded their guns while they were in the ditch, came up and fired upon the enemy, who part ran away and some surrendered so that we entered the redoubt without further opposition. (More here; I’ve added a lot of punctuation)

Joseph Plumb Martin, whom we met as a grunt at the Battle of Monmouth, was present at the storming of Redoubt 10 as a sapper. His job was to go in ahead of the troops and clear away the obstructions. Martin’s account (published in 1830) includes such charming details as the fact that the watchword, “Rochambeau,” if pronounced quickly sounded like “Rush-an-boys.” You really should read it: here.

The aftermath of the attacks on Redoubts 9 and 10

Hamilton’s troops suffered fewer than 50 killed and wounded. He reported to Lafayette the next day:

The killed and wounded of the enemy did not exceed eight. Incapable of imitating examples of barbarity, and forgetting recent provocations, the soldiery spared every man, who ceased to resist. (More here)

The barbarity Hamilton refers to was a recent raid of New London, Connecticut, led by Benedict Arnold. The British brutally slaughtered 85 Americans who surrendered there. Sixty more were wounded, many mortally.

Despite the fact that we have Hamilton’s own after-action report, uncertainties abound regarding Hamilton’s doings before and during the storming of Redoubt 10, including whether he was originally given the command and what he did while leading the attack. If this interests you, you can’t possibly do better than reading Chapters 39 and 40 in Michael Newton’s Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years. No, I can’t summarize (she said snappishly, casting a bleary eye at her 10-page blog post).

By the next morning (October 15), Redoubts 9 and 10 had been incorporated into the second line of trenches, and the British in Yorktown were being ceaselessly bombarded from a few hundred yards away.

Cornwallis wrote to Clinton that day:

Sir Last evening the enemy carried my two advanced redoubts on the left by storm, and during the night have included them in their second parallel which they are at present busy in perfecting. My situation now becomes very critical; we dare not shew a gun to their old batteries and I expect that their new ones will open to morrow morning; experience has shewn that our fresh earthen works do not resist their powerful artillery, so that we shall soon be exposed to an assault, in ruined works, in a bad position and with weakened numbers. The safety of the place is therefore so precarious that I cannot recommend that the fleet and army should run great risque in endeavouring to save us. I have the honour to be & c CORNWALLIS (More here; some punctuation added)

On October 17, Saint George Tucker noted in his journal:

An officer’s Baggage by some means or other fell into our hands by the running on shore of a Boat destin’d for N. York. A Journal of the Siege to yesterday was found—In it this remarkable Conclusion—Our provisions are now nearly exhausted & our Ammunition totally. (More here)

More

- The 235th anniversary of the Siege of Yorktown is coming up in mid-October, with appropriate celebrations. After reading this post, how can you (and I!) not want to “learn the steps leading up to the firing of an artillery piece, followed by its firing”? Somebody better post videos!

- The numbers of troops and artillery pieces, the distances between trenches, and many other details above are taken from primary sources, which tend not to agree. For the latest scholarly thoughts on the details, read one of the many recent books on the Siege of Yorktown, such as Thomas Fleming’s Beat the Last Drum: The Siege of Yorktown. (A well-told story, but dude, where are the footnotes and bibliography?!?!?!?)

- Captain Stephen Olney’s account mentions men being chosen for “the forlorn hope.” Turns out that’s a military term for a small group of soldiers who take the lead in an attack, right behind the sappers, hence are more likely to suffer casualties.

- Redoubt 10 at modern Yorktown is a reconstruction. Most of the original redoubt toppled over the bluff and into the river.

- I’ve started adding comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical: a fantastic resource. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the thirty-fourth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. My intro to this series is here. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.