The British fleet arrives

The British fleet arrives

General George Washington to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress:

New York July the 3d 1776

Sir

Since I had the honor of addressing you and on the same day, several Ships more arrived within the Hook, making the number that came in then a hundred & Ten, and there remains no doubt of the whole of the Fleet from Hallifax being now here. Yesterday evening fifty of them came up the Bay, and Anchored on the Staten Island side. …

Our reinforcement of Militia is but yet small. I cannot ascertain the amount not having got a return. However I trust if the Enemy make an Attack they will meet with a repulse, as I have the pleasure to inform you, that an agreable spirit and willingness for Action seem to animate and pervade the whole of our Troops. …

I must entreat your attention to an Application I made some time ago for Flints, we are extremely deficient in this necessary Article, and shall be greatly distressed if we cannot obtain a Supply. Of Lead we have a sufficient quantity for the whole Campaign taken off the Houses here.

Esteeming It of Infinite advantage to prevent the Enemy from getting fresh provisions and Horses for their Waggons, Artillery &c. I gave orders to a party of our men on Staten Island since writing Genl Herd to drive the Stock off, without waiting for the assistance or direction of the Committees there, lest their slow mode of transacting business might produce too much delay …

I have the Honor to be with Sentiments of the greatest Esteem Sir Your Most Obedt Servt

Go: Washington (full text here)

Did you notice that the commander in chief is personally writing to Congress begging for flints for firearms? No wonder he asked for a larger staff (more right-hand men) a few weeks later.

Washington literally didn’t know the half of what he was facing: more than 300 ships transporting 32,000 men. When the British disembarked on Staten Island, it was the largest amphibious attack of the eighteenth century, unsurpassed until the Normandy Invasion in 1944. [NOTE: I’m taking the ship and troop numbers from Chernow’s Hamilton, p. 76, but I wish I had a good contemporary source on them! Yo, anybody?]

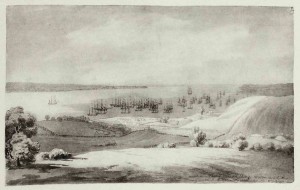

Depending on the wind, the British could have either landed in Brooklyn and marched through it toward New York, or sailed north to land directly in Manhattan. (For maps of the city at that time, see my post on New York ca. 1776.) Washington split his force of 20,000 so he could defend both possible landing points.

ANOTHER NOTE: I’m going to use modern street and neighborhood names below, because I like picturing the Revolutionary War military actions overlaid on today’s grid. So …

The British invade Brooklyn

A bit earlier than 1776 – something like 18,000 years ago – the Wisconsin Ice Sheet retreated, leaving a glacial moraine in Brooklyn. At its western end, the moraine includes a ridge that runs from the area around the Green-wood Cemetery northeast through Jamaica. The ridge is that brownish area on the map below.

Unless you’re the noble Duke of York, you don’t march your men to the top of the hill and march them down again. (Mom joke. That song, animated here, is even older than “The World Turned Upside Down.”) If you’re moving thousands of men, you look for passes through the hills.

General Howe ordered his troops ferried across to Brooklyn at about the point where the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge now stands. Then he split them, sending some northeast roughly along the path of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, where they ran into the American defenses at a pass just north of the Green-Wood Cemetery. Another British contingent headed northeast through what’s now Bensonhurst and Borough Park. That contingent split, with one part attacking American defenses at a pass in Prospect Park.

The final contingent – the largest, with some 10,000 men – was the one that caused the Americans to lose the Battle of Brooklyn. It marched down Flatbush and then northeast up Flatlands. Way out there where Jamaica, East New York, and Bushwick Avenues meet (think LIRR Jamaica Station), the British troops marched through Jamaica Pass. The Americans had not defended that one: it lay five miles away, and the Americans were already spread thin. These British troops swung around to approach the American forces from the east while Howe’s other contingents continued their attack from the south. At 8 a.m., two cannons boomed, indicating that the last contingent was in place. The trap snapped shut. By noon, the Americans were on the run.

Below is the account of Michael Graham, an 18-year-old American militia volunteer who fought at the Battle of Long Island. It’s long and not particularly well written, but read it anyway: as an expression of the desperation and despair felt by the American troops surrounded by British regulars, it’s difficult to top. Graham is describing the fighting between Lord Stirling’s American troops and the British near the Old Stone House, just west of Prospect Park. The swamp he mentions is the area around the Gowanus Canal.

On the next morning, the battle commenced about the break of day or perhaps a little before. At the Narrows, where Lord Stirling commanded, there was a pretty heavy cannonading kept up and occasionally the firing of small arms, and from the sound appeared to be moving slowly towards Brooklyn. This continued for hours. At length the firing commenced above us and kept spreading until it became general almost in every direction. We continued at our post until I think about twelve o’clock, when an officer came and told us to make our escape, for we were surrounded. We immediately retreated towards our camp. We had went but a small distance before we saw the enemy paraded in the road before us. We turned to the left and posted ourselves behind a stone fence; from the movements of the enemy, we had soon to move from this position. Here we got parted, and I neither saw officers or men belonging to our party (with the exception of one man) during the balance of that day. I had went but a small distance before I came to a party of our men making a bold stand. I stopped and took one fire at the enemy, but they came on with such rapidity that I retreated back in the woods. Here I met Colonel Miles, a regular officer from Pennsylvania, and Lieutenant Sloan, a full cousin of my own. As soon as I had loaded my gun, I left them (Colonel Miles was taken prisoner and Lieutenant Sloan killed), as the firing had ceased where I had retreated from. I returned to near the same place. I had not been at this place I think more than one minute before the British came in a different direction from where they were when I retreated, firing platoons as they marched. I turned and took one fire at them and then made my escape as fast as I could. By this time our troops were routed in every direction. It is impossible for me to describe the confusion and horror of the scene that ensued: the artillery flying with the chains over the horses’ backs, our men running in almost every direction, and run which way they would, they were almost sure to meet the British or Hessians. And the enemy huzzahing when they took prisoners made it truly a day of distress to the Americans. I escaped by getting behind the British that had been engaged with Lord Stirling and entered a swamp or marsh through which a great many of our men were retreating. Some of them were mired and crying to their fellows for God’s sake to help them out; but every man was intent on his own safety and no assistance was rendered. At the side of the marsh there was a pond which I took to be a millpond. Numbers, as they came to this pond, jumped in, and some were drowned. Soon after I entered the marsh, a cannonading commenced from our batteries on the British, and they retreated, and I got safely into camp. Out of the eight men that were taken from the company to which I belonged the day before the battle on guard, I only escaped. The others were either killed or taken prisoners. At the time, I could not account for how it was that our troops were so completely surrounded but have since understood there was another road across the ridge several miles above Flatbush that was left unoccupied by our troops. Here the British passed and got betwixt them and Brooklyn unobserved. This accounts for the disaster of that day. (Online here.)

For the Maryland Monument in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, see here.

The Maryland 400

With the British attacking from several sides, Lord Stirling chose the best-trained and best-equipped unit in the American army to remain with him, covering the retreat of the rest of his troops from the Stone House across the Gowanus swamp to Brooklyn Heights to meet Washington and his troops. For hours, Sitrling and a few hundred members of the Maryland Regiment fought an holding action against 2,000 British troops. Two hundred fifty-six of them died. Only a dozen survived. Washington, taking a last look at the battle from the heights, is said to have lamented, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose.”

History is a series of what-if moments … but some are more decisive than others. If the British had kept marching and trapped the Americans against the river in Brooklyn Heights, the British would have killed or captured the American army’s commander in chief and most of his troops. The American Revolution would have gone down in history as an unsuccessful rebellion, rather than as the War of Independence. So if you visit the monument to the Maryland 400 in the southern end of Prospect Park, take off your hat, salute, or bow your head: do whatever it is you do to show profound respect.

Retreat to Manhattan

On the night of August 29-30, 1776, the American troops were ferried from Brooklyn to Manhattan. Washington wrote to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress.

New York Augt 31st 1776

Sir

Inclination as well as duty would have Induced me to give Congress the earliest Information of my removal and that of the Troops from Long Island & Its dependencies to this City the night before last, But the extreme fatigue whic⟨h⟩ myself and Family have undergone as much from the Weather since the Engagement on the 27th rendered me & them entirely unfit to take pen in hand—Since Monday scarce any of us have been out of the Lines till our passage across the East River was effected Yesterday morning & for Forty Eight Hours preceding that I had hardly been of[f] my Horse and never closed my Eyes so that I was quite unfit to write or dictate till this Morning.

Our Retreat was made without any Loss of Men or Ammunition and in better order than I expected from Troops in the situation ours were—We brought off all our Cannon & Stores, except a few heavy peices, which in the condition the earth was by a long continued rain, we found upon Trial impracticable—The Wheels of the Carriages sinking up to the Hobs, rendered it impossible for our whole force to drag them—We left but little provisions on the Island except some Cattle which had been driven within our Lines and which after many attempts to force across the Water we found Impossible to effect, circumstanced as we were …

In the Engagement on the 27th Generals Sullivan & Stirling were made prisoners … Nor have I been yet able to obtain an exact account of Our Loss, we suppose It from 700 to a Thousand, killed & taken—Genl Sullivan says Lord Howe is extremely desirous of seeing some of the Members of Congress for which purpose he was allowed to come out & to communicate to them what was passed between him & his Lordship—I have consented to his going to Philadelphia, as I do not mean or conceive It right to withold or prevent him from giving such information as he possesses in this Instance. …

I am with my best regards to Congress Their & Your Most Obedt He Servt

Go: Washington (whole letter here)

Hostilities paused for ten days while Howe went to New Jersey to speak to delegates from Congress. On September 11, 1776, Edward Rutledge reported the results to Washington:

I must beg Leave to inform you that our Conferrence with Lord Howe has been attended with no immediate Advantages—He declared that he had no Powers to consider us as Independt States, and we easily discover’d that were we still Dependt we would have nothing to expect from those with which he is vested—He talk’d altogether in generals, that he came out here to consult, advise, & confer with Gentlemen of the greatest Influence in the Colonies about their Complaints, that the King would revise the Acts of Parliament & royal Instructions upon such Reports as should be made and appear’d to fix our Redress upon his Majesty’s good Will & Pleasure—This kind of Conversation lasted for several Hours & as I have already said without any Effect—Our Reliance continues therefore to be (under God) on your Wisdom & Fortitude & that of your Forces—That you may be as succesful as I know you are worthy is my most sincere wish … (Whole letter here)

Kips Bay

On September 15, British troops landed in Manhattan and fought the Americans at Kips Bay – on the east side in the 20s. This map drawn by the British after they occupied Manhattan happens to be the earliest accurate topographical map of the island. Kips Bay is below the “N” in “North River,” if you can read that tiny print. Or look for the first large cove as you work your way up the east side of the island.

General Washington to John Hancock, September 16, 1776, from Col. Roger Morris’s House [i.e., the Morris-Jumel Mansion]:

About Eleven OClock those in the East River began a most severe and Heavy Cannonade to scour the Grounds and cover the landing of their Troops between Turtle-Bay and the City, where Breast Works had been thrown up to oppose them. As soon as I heard the Firing, I road with all possible dispatch towards the place of landing when to my great surprize and Mortification I found the Troops that had been posted in the Lines retreating with the utmost precipitation and those ordered to support them, parson’s & Fellows’s Brigades, flying in every direction and in the greatest confusion, notwithstanding the exertions of their Generals to form them. I used every means in my power to rally and get them into some order but my attempts were fruitless and ineffectual, and on the appearance of a small party of the Enemy, not more than Sixty or Seventy, their disorder increased and they ran away in the greatest confusion without firing a Single Shot—Finding that no confidence was to be placed in these Brigades and apprehending that another part of the Enemy might pass over to Harlem plains and cut off the retreat to this place, I sent orders to secure the Heights in the best manner with the Troops that were stationed on and near them, which being done, the retreat was effected with but little or no loss of Men, tho of a considerable part of our Baggage occasioned by this disgracefull and dastardly conduct—Most of our Heavy Cannon and a part of our Stores and provisions which we were about removing was unavoidably left in the City, tho every means after It had been determined in Council to evacuate the post, had been used to prevent It. We are now encamped with the Main body of the Army on the Heights of Harlem where I should hope the Enemy would meet with a defeat in case of an Attack, If the Generality of our Troops would behave with tolerable bravery, but experience to my extreme affliction has convinced me that this is rather to be wished for than expected; However I trust, that there are many who will act like men, and shew themselves worthy of the blessings of Freedom. I have sent out some reconoitring parties to gain Intelligence If possible of the disposition of the Enemy and shall inform Congress of every material event by the earliest Opportunity. I have the Honor to be with the highest respect Sir Your Most Obedt Sert. (Complete text here)

It was at the Battle of Kips Bay that Washington, losing his temper, is reported to have said, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?” The line is quoted in Flexner’s biography of Washington and McCullough’s 1776. I’d love to have the reference to the original source – anyone own either?

Retreat to Harlem

General Orders from General Washington for September 17, 1776, at Headquarters, Harlem Heights:

Parole: Leitch. Countersign: Virginia.

The General most heartily thanks the troops commanded Yesterday, by Major Leitch, who first advanced upon the enemy, and the others who so resolutely supported them—The Behaviour of Yesterday was such a Contrast, to that of some Troops the day before, as must shew what may be done, where Officers & soldiers will exert themselves—Once more therefore, the General calls upon officers, and men, to act up to the noble cause in which they are engaged, and to support the Honor and Liberties of their Country. … (Complete text here)

America seeks French aid

A week after the orders above, on September 30, 1776, Congress dispatched Benjamin Franklin and Charles Lee as American commissioners to France. Along with Silas Deane (who was already in Paris), they were tasked with negotiating a treaty to get French aid against France’s old foe, Great Britain. The treaty was signed on February 6, 1778, delivered to Congress on May 2, 1778, and ratified by Congress two days later. But that was long in the future in the autumn of 1776.

Retreat to Westchester

On October 20, 1776, General Washington wrote to Robert R. Livingston from a farmhouse in Westchester County. Livingston was one of the Committee of Five who drafted the Declaration of Independence.

Dear Sir,

I wish I had leizure to write you fully on the subject of yr last Letter—the moving state of the Army, and the extreame hurry in which I have been Involved for these Eight days, will only allow me time to acknowledge the receipt of yr favour, and to thank you (as I shall always do) for Any hints you may please to communicate, as I have great reliance upon your judgment; & knowledge of the Country, (which I wish to God I was as much master of) …

Let me Intreat you my Dear Sir, to use your Influence to send, without delay, Provisions for this Army, towards the White Plains—upon a strict scrutiny, I find an alarming deficiency herein, occasioned by the Commissary’s placing too much confidence in his Water Carriage, and the Stock he had laid in at the Saw pits &ca (which but too probably may be cut of from us, althô upon the first knowledge I had of Its being there, I ordered it to be remov’d)—We want both Flour, & Beef; & I entreat your exertions to forward them. I must also entreat you to send us a Number of Teams the more the better to aid in removing the Army as occasion requires. We are amazingly distress’d on Acct of the want of them—We can move nothing for want of them—In short Sir, our Situation is really distressing. I have orderd Lord Sterling with upwards of 2000 Men to the White Plains to prevent the Enemys taking possession of it, & for security of Our Stores there; but the Troops were obliged to March without their Tents, or Baggage. In exceeding great haste, & much sincerety I am Dr Sir Yr Most Obedt and obligd Sert

Go: Washington (Full text here)

More

- Re Battering down the Battery: I haven’t seen references to fighting there between the British and Americans summer and autumn of 1776. Hercules Mulligan’s account of his time with Alexander Hamilton describes them stealing cannon from the Battery in 1775, though: see here.

- I’ve occasionally added comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the seventeenth in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.