Why, where, and whither the Annapolis Convention?

Why, where, and whither the Annapolis Convention?

For the past several posts, we’ve focused on Hamilton’s activities as a lawyer in New York in the 1780s: defending former loyalists and working with the Bank of New York and the New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves. He’s about to step back onto the national stage, at the Annapolis Convention in September 1786, so we need to pull back to a wider perspective. What’s the state of the union?

In a word: helluvamess.

In seven words: Economic depression leading to short-sighted, cut-throat behavior.

- Trade: plummeting. Britain, formerlyAmerica’s largest market, was punishing its former colonies via commercial restrictions. British ports could not import American fish, beef, and whale oil. Grain imports were permitted, but heavily taxed.

- Debt: still rising. The war had been run on credit. Five years after the war ended, not even the interest – much less the principal – was being paid. The soldiers, merchants, farmers, wagon-makers, &c. &c. &c. who had provided manpower or goods to the war effort wanted (and deserved!) to be paid. By someone. Somehow. Now, or sooner.

- Money in circulation: erratic. Foreign gold and silver coins remained in circulation, but were exceedingly scarce and in high demand: everyone preferred to be paid in metal. What they usually got instead was state- or federal-issued paper money or securities, whose value fluctuated wildly depending on who issued it and the political and economic situation. Yesterday you sold a loaf of bread for paper that would buy you a quart of milk. A month from now, that paper might buy you half a quart. In the face of such uncertainty, how will you plan long-term for your family, your business, your life?

James Madison commented on this situation on March 18, 1786, in one of his periodic updates to Thomas Jefferson, who was American ambassador in Paris:

Another unhappy effect of a continuance of the present anarchy of our commerce will be a continuance of the unfavorable balance on it, which by draining us of our metals furnishes pretexts for the pernicious substitution of paper money, for indulgences to debtors, for postponements of taxes. In fact most of our political evils may be traced up to our commercial ones, as most of our moral may to our political. (More here)

What to do? Don’t look for help to the Congress of the Confederation.

Nobody’s Congress

After the Pennsylvania Mutiny in June 1783 (more here), Congress became an itinerant assembly, now in Princeton, now Trenton, now New York. It still relied solely on the goodwill of the states for its income. But with the War for Independence won, the states became even more reluctant to pay their allotted shares toward supporting a national government. Congressional resolutions were ignored. Appointed delegates didn’t bother to attend congressional sessions. In the years immediately following the war, from 1783 to early 1787, Congress passed only two measures of long-term significance: the Land Ordinances of 1784 and 1785.

The states go their own ways

Lacking guidance from a strong national government (not that they wanted it!), the states tackled their economic woes with an every-state-for-itself approach. By the mid-1780s, eight of them had imposed trade duties not only on foreign imports, but on imports from other states. Seven states had issued yet more paper money.

And then there was the national debt. Back in April 1781, in his first letter to Robert Morris, Hamilton pointed out the benefit of a national debt: “A national debt if it is not excessive will be to us a national blessing; it will be powerfull cement of our union.” (More here.) As superintendent of Finance from 1781 to 1784, Robert Morris had acted on the same premise: if the states owed money jointly, they would become accustomed to working together.

But by the mid-1780s, American citizens who were still owed money from the Revolutionary War (Yorktown 1781, treaty 1783) were getting restless. In 1786 and 1787, Pennsylvania and New York, under pressure from their own citizens who were owed money by the federal government, took over (“assumed”) their share of the national debt and paid it off … with new issues of paper money. This was yet another step toward the demise of the union.

The Mount Vernon Compact

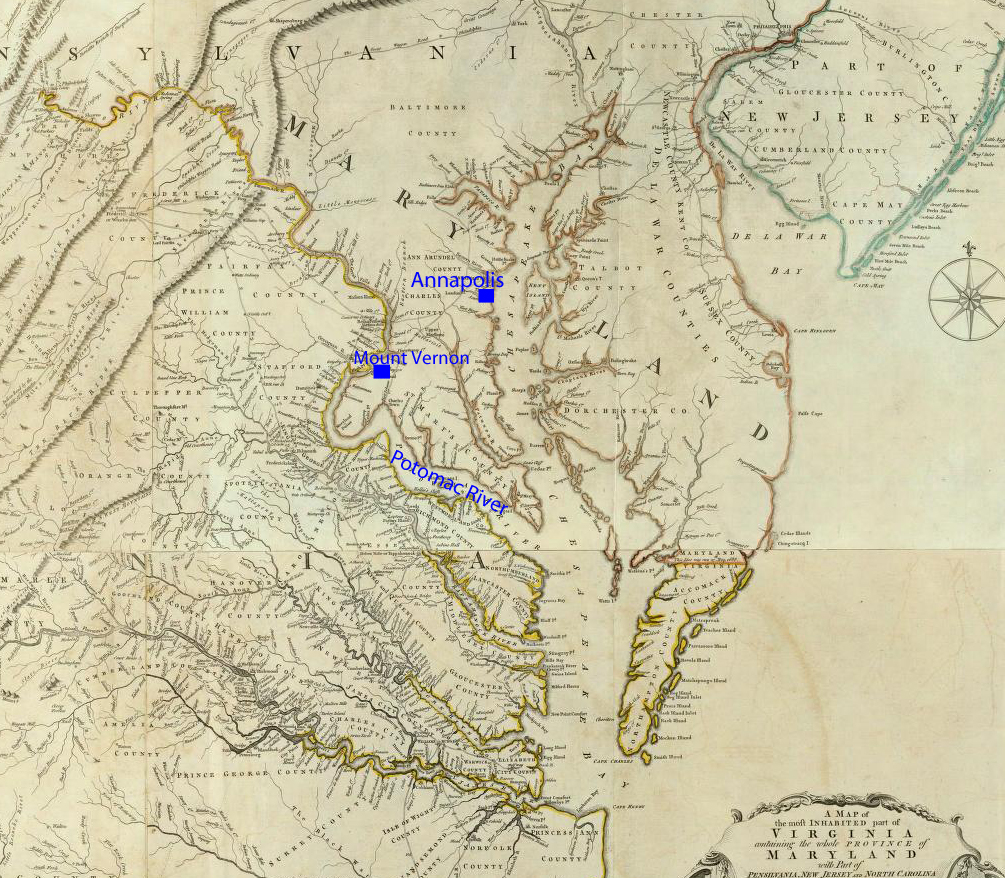

In hindsight, the turning point in this downward, centrifugal spiral was an action of James Madison, one of Hamilton’s colleagues in the 1782-1783 session of the Confederation Congress, and like Hamilton, a proponent of a strong national government. In 1783, Madison proposed a meeting of commissioners from Maryland and his native Virginia to resolve the thorny question of who would collect import duties on the Potomac River.

Just in case your VA-MD geography is as wonky as mine was, here’s the way things look.

The event was a near-fiasco. Governor of Virginia Patrick Henry failed to inform the Virginia delegates that they had been chosen. When the Maryland commissioners arrived in Alexandria in early 1785, they found no opposite numbers with whom to negotiate.

The event was a near-fiasco. Governor of Virginia Patrick Henry failed to inform the Virginia delegates that they had been chosen. When the Maryland commissioners arrived in Alexandria in early 1785, they found no opposite numbers with whom to negotiate.

General George Washington (U.S. Army, Ret.) yet again saved the day. He invited the Maryland and Virginia commissioners to stay at Mount Vernon, his estate on the Potomac. By March 25, 1785, they hammered out a series of thirteen agreements.

The issues covered by the “Mount Vernon Compact” illustrate the narrow-minded pettiness that drove the actions of Maryland and Virginia, and (with variations) the other eleven states. Among the provisions:

- Virginia will not impose any toll, duty, or charge upon ships sailing through Chesapeake Bay to Maryland.

- Virginian ships may enter Maryland ports as harbor, or for safety against enemies, without payment of any charge.

- Citizens of Maryland and Virginia can both fish in the Potomac.

- Pirates will be prosecuted. (This is by far the longest article.)

- Those who own property in both Maryland and Virginia can move it from one state to the other without being taxed. (More here.)

The Annapolis Convention

The Mount Vernon Compact was duly confirmed by the Virginia and Maryland legislatures. Then, prompted again by James Madison, the Virginia legislature issued an invitation to a meeting by delegates from all thirteen states,

to take into consideration the trade of the United States; to examine the relative situation and trade of the said States to consider how far a uniform system in their commercial regulations may be necessary to their common interest and their permanent harmony … (1/21/1786; more here)

The meeting was set for Annapolis, Maryland. Why? Because it’s in the middle of nowhere. James Madison explained to Thomas Jefferson on March 18, 1786:

It was thought prudent to avoid the neighbourhood of Congress, and the large Commercial towns, in order to disarm the adversaries to the object of insinuations of influence from either of these quarters. (More here)

Madison did not have high hopes for the Annapolis Convention, but he saw no other option:

I almost despair of success. It is necessary however that something should be tried and if this be not the best possible expedient, it is the best that could possibly be carried thro’ the Legislature here. And if the present crisis cannot effect unanimity, from what future concurrence of circumstances is it to be expected? (to Thomas Jefferson 3/18/1786; more here)

Only five states sent commissioners to Annapolis: Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. Four other states appointed commissioners who didn’t show: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and North Carolina. The remaining four – Connecticut, South Carolina, Georgia, and host state Maryland – did not appoint commissioners.

The Commissioners met at Annapolis for three days. On September 14, 1786, they issued the “Annapolis Address.” According to James Madison, the document was the work of Alexander Hamilton.

Are we surprised? Not really. Back in July 1783, Hamilton had drafted a 2,300-word resolution that listed twelve serious defects of the Articles of Confederation and issued a rousing call for a convention to remedy them. His manuscript draft includes the bitter note, “Resolution intended to be submitted to Congress at Princeton in 1783; but abandoned for want of support” (in full here, my summary here).

The gist of the Annapolis Address, quoted at length below, is: 1) We need a meeting of all the states; 2) We need to consider not just commercial matters, but all matters concerning the federal government; and 3) The meeting should be held in Philadelphia in May 1787. Less obvious: Hamilton is pussy-footing about in the Annapolis Address in a way he seldom (never?) does when writing solely on his own account. The subtext – and not very sub, at that – is: “I could go on and on about the defects of the Articles of Confederation, but it would be a ‘useless intrusion of facts and observations’ because we all know what a mess it is.”

Deeply impressed however with the magnitude and importance of the object confided to them on this occasion, your Commissioners cannot forbear to indulge an expression of their earnest and unanimous wish, that speedy measures may be taken, to effect a general meeting, of the States, in a future Convention, for the same and such other purposes, as the situation of public affairs, may be found to require.

If in expressing this wish, or in intimating any other sentiment, your Commissioners should seem to exceed the strict bounds of their appointment, they entertain a full confidence, that a conduct, dictated by an anxiety for the welfare, of the United States, will not fail to receive an indulgent construction.

In this persuasion your Commissioners submit an opinion, that the Idea of extending the powers of their Deputies, to other objects, than those of Commerce, which has been adopted by the State of New Jersey, was an improvement on the original plan, and will deserve to be incorporated into that of a future Convention; they are the more naturally led to this conclusion, as in the course of their reflections on the subject, they have been induced to think, that the power of regulating trade is of such comprehensive extent, and will enter so far into the general System of the foederal government, that to give it efficacy, and to obviate questions and doubts concerning its precise nature and limits, may require a correspondent adjustment of other parts of the Fœderal System.

That there are important defects in the system of the Fœderal Government is acknowledged by the Acts of all those States, which have concurred in the present Meeting; That the defects, upon a closer examination, may be found greater and more numerous, than even these acts imply, is at least so far probable, from the embarrassments which characterise the present State of our national affairs—foreign and domestic, as may reasonably be supposed to merit a deliberate and candid discussion, in some mode, which will unite the Sentiments and Councils of all the States. In the choice of the mode your Commissioners are of opinion, that a Convention of Deputies from the different States, for the special and sole purpose of entering into this investigation, and digesting a plan for supplying such defects as may be discovered to exist, will be entitled to a preference from consideration, which will occur, without being particularised.

Your Commissioners decline an enumeration of those national circumstances on which their opinion respecting the propriety of a future Convention with more enlarged powers, is founded; as it would be an useless intrusion of facts and observations, most of which have been frequently the subject of public discussion, and none of which can have escaped the penetration of those to whom they would in this instance be addressed. They are however of a nature so serious, as, in the view of your Commissioners to render the Situation of the United States delicate and critical, calling for an exertion of the united virtue and wisdom of all the members of the Confederacy.

Under this impression, Your Commissioners, with the most respectful deference, beg leave to suggest their unanimous conviction, that it may essentially tend to advance the interests of the union, if the States, by whom they have been respectively delegated, would themselves concur, and use their endeavours to procure the concurrence of the other States, in the appointment of Commissioners, to meet at Philadelphia on the second Monday in May next, to take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Fœderal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union; and to report such an Act for that purpose to the United States in Congress Assembled, as when agreed to, by them, and afterwards confirmed by the Legislatures of every State will effectually provide for the same. (More here)

May 1787 seems a long way off, given the precarious state of the union in September 1786. News of Shays’s Rebellion (see below) would perhaps have percolated down to Annapolis as the commissioners were meeting. But given how slow communication and transportation were in the 1780s, and given that winter was approaching, May 1787 was the earliest reasonable date.

The commissioners dispatched the Annapolis Address to the legislatures of their respective states. They also sent copies to Congress and to the legislatures of states that had not attended. Within months, five states, including the important states of Virginia and Pennsylvania, had appointed delegates to the Philadelphia Convention.

Congress reacts to the call for a convention

Congress – a national body full of delegates who didn’t believe in a strong national government – shelved the Annapolis Address for five months. In February 1787, they endorsed a convention at Philadelphia, but restricted its scope:

Resolved that in the opinion of Congress it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a Convention of delegates who shall have been appointed by the several states be held at Philadelphia for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation and reporting to Congress and the several legislatures such alterations and provisions therein as shall when agreed to in Congress and confirmed by the states render the federal constitution adequate to the exigencies of Government & the preservation of the Union. (More here)

The proviso that the Philadelphia Convention was only allowed to revise the Articles of Confederation – not to create a whole new framework for government – was to cause considerable strife at the Convention.

Hamilton, who was serving in the New York State Assembly in 1786-1787, lobbied there for sending delegates to the Philadelphia Convention. In February, he was chosen to represent New York. To keep a lid on him, though, his co-delegates were John Lansing, Jr., and Robert Yates, both of whom were vigorously opposed to giving the federal government more power.

Shays’s Rebellion, August 1786

In August 1786, just before the Annapolis Convention met, disgruntled debtors in Massachusetts rebelled against the government. Led by Daniel Shays, they shut down courts and plotted to seize weapons from a United States armory.

Hamilton had a long-standing fear of anarchy (see his letter to John Jay of 11/26/1775) – but as 1786 rolled into 1787, he was not alone in fearing that the existence of the United States was at risk.

Tench Tilghman (a former aide-de-camp of Washington) wrote to his father on February 5, 1786:

It is a melancholy truth, but so it is that we are at this point in time the most contemptible and abject nation on the face of the earth. We have neither reputation abroad nor union at home. We hang together merely because it is not in the interest of any other power to shake us to pieces, and not from any well-cemented bond of our own. (Quoted in Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution, p. 426)

Arthur Lee wrote to Richard Henry Lee on April 19, 1786:

We have independence without the means of attaining it; and are a nation without one source of national defense … we don’t seem to feel these things are necessary to national existence. The Confederation is crumbling to pieces. (Quoted in Rappleye, p. 426)

On November 5, 1786, two months after the Annapolis Convention, George Washington wrote to James Madison. His comments on Shays’s Rebellion and the state of the nation were surely meant to be shared.

Fain would I hope, that the great, & most important of all objects—the foederal governmt.—may be considered with that calm & deliberate attention which the magnitude of it so loudly calls for at this critical moment: Let prejudices, unreasonable jealousies, and local interest yield to reason and liberality. Let us look to our National character, and to things beyond the present period. No morn ever dawned more favourable than ours did—and no day was ever more clouded than the present! Wisdom, & good examples are necessary at this time to rescue the political machine from the impending storm. Virginia has now an opportunity to set the latter, and has enough of the former, I hope, to take the lead in promoting this great & arduous work.

Without some alteration in our political creed, the superstructure we have been seven years raising at the expence of much blood and treasure, must fall. We are fast verging to anarchy & confusion! A letter which I have just received from Genl Knox, who had just returned from Massachusetts (whither he had been sent by Congress consequent of the Commotion in that State) is replete with melancholy information of the temper & designs of a considerable part of that people. Among other things he says, “there creed is, that the property of the United States, has been protected from confiscation of Britain by the joint exertions of all, and therefore ought to be the common property of all. And he that attempts opposition to this creed is an enemy to equity & justice, & ought to be swept from off the face of the Earth.” Again “They are determined to anihilate all debts public & private, and have Agrarian Laws, which are easily effected by the means of unfunded paper Money which shall be a tender in all cases whatever.” He adds, “The numbers of these people amount in Massachusetts to about one fifth part of several populous Counties, and to these may be collected, people of similar sentiments from the States of Rhode Island, Connecticut, & New Hampshire so as to constitute a body of twelve or fifteen thousand desperate, and unprincipled men. They are chiefly of the young & active part of the Community.”

How melancholy is the Reflection, that in so short a space, we should have made such large strides towards fulfilling the prediction of our transatlantic foe! “Leave them to themselves, and their government will soon dissolve.” Will not the wise & good strive hard to avert this evil? Or will their supineness suffer ignorance and the arts of self interested designing disaffected & desperate characters, to involve this rising empire in wretchedness & contempt? What stronger evidence can be given of the want of energy in our governments than these disorders? If there exists not a power to check them, what security has a man of life, liberty, or property?

To you, I am sure I need not add aught on this subject, the consequences of a lax, or inefficient government, are too obvious to be dwelt on. Thirteen sovereignties pulling against each other, and all tugging at the foederal head will soon bring ruin on the whole; whereas a liberal, and energetic Constitution, well guarded, & closely watched, to prevent incroachments, might restore us to that degree of respectability & consequence, to which we had a fair claim, & the brightest prospect of attaining. With sentiments of the sincerest esteem & regard I am Dear Sir Yr. most Obedt. & affect Hble servt.

Go: Washington (More here; I’ve added a few paragraph breaks above)

Jefferson on Shays’s Rebellion

The only one not distressed by Shays’s Rebellion was Thomas Jefferson, still in Paris. On January 30, 1787, he wrote to Madison:

I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, & as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical. (More here)

More

- On the Mount Vernon Compact, I’ve relied on information from the Mount Vernon site and the Heritage Foundation.

- I’ve just finished Charles Rappleye’s Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution (2011), and I’m wondering how I got along before I read it. I’ve never seen so good a summary of America’s early finances, and it’s worked into the story of Morris’s life, so it reads like, well, a story. Excellent.

- Jefferson’s more extreme statement on rebellion, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants,” was written 11/13/1787 to Col. William Stephens Smith; more here.

- I’ve started adding comments based on these blog posts to the Genius.com pages on the Hamilton Musical. Follow me @DianneDurante.

- The usual disclaimer: This is the fifty-first in a series of posts on Hamilton: An American Musical. My intro to this series is here. Other posts are available via the tag cloud at lower right. The ongoing “index” to these posts is my Kindle book, Alexander Hamilton: A Brief Biography. Bottom line: these are unofficial musings, and you do not need them to enjoy the musical or the soundtrack.

- Want wonderful art delivered weekly to your inbox? Check out my free Sunday Recommendations list and rewards for recurring support: details here.